1. Finding a Footing: Th E North Before 1700

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine News Iucn Global Marine and Polar Programme

MARINE NEWS IUCN GLOBAL MARINE AND POLAR PROGRAMME ISSUE 12 - NOVEMBER 2015 Climate Change Adaptation Special MARINE NEWS Issue 12 -November 2015 In this Issue... IUCN Global Marine and Polar Programme 1 Editorial Rue Mauverney 28 By Pierre-Yves Cousteau 1196 Gland, Switzerland Tel +4122 999 0217 Fax +4122 999 0002 2 Overview of the GMPP www.iucn.org/marine 4 Global Threats Editing and design: Oceans and Climate Change, Alexis McGivern © Pierre-Yves Cousteau Ocean Warming, Ocean Acidifi- Back issues available cation, Plastic pollution The ocean is our future; for better or externalisation of environmental costs beginning of the “digitization of the at: www.iucn.org/about/ for worse. (to abolish the business practice of Earth”. How will Big Data shape con- work/programmes/marine/ deferring onto society and natural servation, sustainable development gmpp_newsletter “There are no passengers on space- capital all the negative impacts of and decision making? 12 Global Coasts ship Earth. We are all crew.” - Mar- economic activities), and the cogni- Front cover: © XL Catlin shall McLuhan, 1965. tive frameworks and values that we We are living a fascinating time, where Blue Solutions and Blue Forests, are conditioned for by mainstream the immense challenges mankind fac- Seaview Survey The advent of agriculture over 10,000 media and politicians (obsession with es are matched by the technological Vamizi, Maldives, WGWAP, BEST years ago had a profound socio-eco- financial success, personal image ability to innovate and adapt. The bar- Top picture: A fire coral be- Initiative nomic impact on mankind. Today and hedonism). These challenges riers that hold us back from designing fore and after bleaching. -

The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 1 Article 3 August 2016 The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Donald E. Warden Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Canadian History Commons, European History Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Medieval History Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Scandinavian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Warden, Donald E. (2016) "The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Extent of Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Prior to Columbus Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my honors thesis committee: Dr. Michael Rulison, Dr. Kathleen Peters, and Dr. Nicholas Maher. I would also like to thank my friends and family who have supported me during my time at Oglethorpe. Moreover, I would like to thank my academic advisor, Dr. Karen Schmeichel, and the Director of the Honors Program, Dr. Sarah Terry. I could not have done any of this without you all. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss1/3 Warden: Indigenous-Norse Contact and Trade Part I: Piecing Together the Puzzle Recent discoveries utilizing satellite technology from Sarah Parcak; archaeological sites from the 1960s, ancient, fantastical Sagas, and centuries of scholars thereafter each paint a picture of Norse-Indigenous contact and relations in North America prior to the Columbian Exchange. -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

3P OHIO. Beyond the Dreamers, and the Approach to the Infernal Regions

beyond the dreamers, and the approach Iona or the Irish were not, perhaps, the Sfcakcspcaro at Sohpol.' of London, has recently proposed a what chance there would be in the to the infernal regions was neiir at hand. first tishers or oven forgotten colonists plan for the abolition of tho liver. It is citv for .him. The country seems small Froni various sources, contemporary & well-known principle of the develop to him; the city large. He feels the 3P The polar ico* snow and darkness were at that strange island. According to nndyquasi-oontemporary, we may form naturally supposed to be pretty near Tacitus an expedition sent by Agricola ment, theory that an organ or limb gqsjsip that-flutters ,about his ears to-be a/trustworthy -general estimate of which is notused-grMual&disappears. disgusting and degrading; and chafes the point where extremes meet. Turn conquered the inhabitants of the Ork Shakespeare's course of inatructioa. ing away from this awful country, the neys -And proceeded so far into the Thus; the ancestral tail of the human under ~the Bondage^ imposed -by Bis OHIO. during his school days. At that time, species disappeared affervprimeval man neighbors through .their surveillance'of Argonauts, with favoring winds, 'sailed Northern Ocean as even to see Thulo as we nave seen, boys usually^ went to into tha ocean of the west, passing (Icelandic a nlace of show and winjtry ceased tQ use it in climbuuzixaaa. ami JUxaLnrltlainm txrwcm^WlLUiaotuma Ha ror^somerea- the latesVsevenuyears or age, BJRTCTP »>M'>T» mj auuvuia -xatxm- vrnv xivsuu Pillars of Hercules (the Straits of Gib the land of the Sviones (SoandinavTans) the practice of cramping tnemvcogetn "— —1 hn tered at once upon the. -

9 · the Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece

9 · The Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece PREPARED BY THE EDITORS FROM MATERIALS SUPPLIED BY GERMAINE AUJAe There is no complete break between the development of That such a change should occur is due both to po cartography in classical and in Hellenistic Greece. In litical and military factors and to cultural developments contrast to many periods in the ancient and medieval within Greek society as a whole. With respect to the world, we are able to reconstruct throughout the Greek latter, we can see how Greek cartography started to be period-and indeed into the Roman-a continuum in influenced by a new infrastructure for learning that had cartographic thought and practice. Certainly the a profound effect on the growth of formalized know achievements of the third century B.C. in Alexandria had ledge in general. Of particular importance for the history been prepared for and made possible by the scientific of the map was the growth of Alexandria as a major progress of the fourth century. Eudoxus, as we have seen, center of learning, far surpassing in this respect the had already formulated the geocentric hypothesis in Macedonian court at Pella. It was at Alexandria that mathematical models; and he had also translated his Euclid's famous school of geometry flourished in the concepts into celestial globes that may be regarded as reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus (285-246 B.C.). And it anticipating the sphairopoiia. 1 By the beginning of the was at Alexandria that this Ptolemy, son of Ptolemy I Hellenistic period there had been developed not only the Soter, a companion of Alexander, had founded the li various celestial globes, but also systems of concentric brary, soon to become famous throughout the Mediter spheres, together with maps of the inhabited world that ranean world. -

What Legal Framework Governs the North Pole?

What legal framework governs the North Pole? Master thesis International Law Tilburg University J.R. Mulder (ANR 865773) Supervisor: Dr M. Goodwin What legal framework governs the North Pole? Table of contents. page Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Define the North Pole area North Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 5 South Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Comparison ----------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Conflicting claims, what is the problem? -------------------------------------------------- 8 Sovereignty ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 Acquisition of territory -------------------------------------------------------------- 13 Sovereignty: jurisdiction and military power ------------------------------------ 14 The legal framework on the sea UN Charter --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 Customary International Law ------------------------------------------------------ 15 General Principles ------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Jurisprudence ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 17 UNCLOS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Schematic overview of zones into the sea ---------------------------------------- 21 The legal framework applied to the North Pole -

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A)

The Cimbri of Denmark, the Norse and Danish Vikings, and Y-DNA Haplogroup R-S28/U152 - (Hypothesis A) David K. Faux The goal of the present work is to assemble widely scattered facts to accurately record the story of one of Europe’s most enigmatic people of the early historic era – the Cimbri. To meet this goal, the present study will trace the antecedents and descendants of the Cimbri, who reside or resided in the northern part of the Jutland Peninsula, in what is today known as the County of Himmerland, Denmark. It is likely that the name Cimbri came to represent the peoples of the Cimbric Peninsula and nearby islands, now called Jutland, Fyn and so on. Very early (3rd Century BC) Greek sources also make note of the Teutones, a tribe closely associated with the Cimbri, however their specific place of residence is not precisely located. It is not until the 1st Century AD that Roman commentators describe other tribes residing within this geographical area. At some point before 500 AD, there is no further mention of the Cimbri or Teutones in any source, and the Cimbric Cheronese (Peninsula) is then called Jutland. As we shall see, problems in accomplishing this task are somewhat daunting. For example, there are inconsistencies in datasources, and highly conflicting viewpoints expressed by those interpreting the data. These difficulties can be addressed by a careful sifting of diverse material that has come to light largely due to the storehouse of primary source information accessed by the power of the Internet. Historical, archaeological and genetic data will be integrated to lift the veil that has to date obscured the story of the Cimbri, or Cimbrian, peoples. -

Introduction EXPLORATION and SACRIFICE: the CULTURAL

Introduction EXPLORATION AND SACRIFICE: THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF ARCTIC DISCOVERY Russell A. POTTER Reprinted from The Quest for the Northwest Passage: British Narratives of Arctic Exploration, 1576-1874, edited by Frédéric Regard, © 2013 Pickering & Chatto. The Northwest Passage in nineteenth-century Britain, 1818-1874 Although this collective work can certainly be read as a self-contained book, it may also be considered as a sequel to our first volume, also edited by Frederic Regard, The Quest for the Northwest Passage: Knowledge, Nation, Empire, 1576-1806, published in 2012 by Pickering and Chatto. That volume, dealing with early discovery missions and eighteenth-century innovations (overland expeditions, conducted mainly by men working for the Hudson’s Bay Company), was more historical, insisting in particular on the role of the Northwest Passage in Britain’s imperial project and colonial discourse. As its title indicates, this second volume deals massively with the nineteenth century. This was the period during which the Northwest Passage was finally discovered, and – perhaps more importantly – the period during which the quest reached an unprecedented level of intensity in Britain. In Sir John Barrow’s – the powerful Second Secretary to the Admiralty’s – view of Britain’s military, commercial and spiritual leadership in the world, the Arctic remained indeed the only geographical discovery worthy of the Earth’s most powerful nation. But the Passage had also come to feature an inaccessible ideal, Arctic landscapes and seascapes typifying sublime nature, in particular since Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818). And yet, for all the attention lavished on the myth created by Sir John Franklin’s overland expeditions (1819-1822, 1825-18271) and above all by the one which would cost him his life (1845-1847), very little research has been carried out on the extraordinary Arctic frenzy with which the British Admiralty was seized between 1818, in the wake of the end of the Napoleonic wars, and 1859, which may be considered as the year the quest was ended. -

PECS Definitions and Rulings

POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME (PECS) ! DEFINITIONS AND RULINGS The Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme is a grading system for extended, unmotorised polar expeditions, crossings or circumnavigations, collectively referred to as Journeys. Polar regions, modes of travel, start and end points, routes and types of support are defined under the scheme and give expeditioners guidance on how to classify, promote and immortalise their journey. PECS uses three tiers of Designation to grade, label and describe polar journeys - a Label (made up of Label Elements), a Description and a MAP Code. Tiers are only an indication of information density. PECS does not discriminate between Modes of Travel. Each Mode is classified under the scheme allowing same-mode journeys to be compared while allowing for superficial cross-comparison. PECS is able to accommodate new modes of unmotorised travel as they develop without impacting on labelling or definitions. Journeys using engines or motors for propulsion, for any part of the journey, are not covered by PECS. PECS concentrates primarily on journeys of more than 400km in Antarctica, Greenland and on the Arctic Ocean however journeys in other polar areas and of less than 400km one-way linear distance that do not include the Poles or significant features on their line of travel may be classified on an informal basis under this scheme. Journeys choosing to use PECS must abide by PECS terminology. Shorter journeys should be labelled accordingly ie. Last Degree South Pole or Double Degree North Pole etc. All rulings and determinations are at the discretion of the PECS Committee. POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME "1 VER190220 CONTENTS 4. -

The Opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, Geopolitical, Environmental, and Socioeconomic Impacts

Marine Policy xxx (xxxx) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Policy journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/marpol The opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, geopolitical, environmental, and socioeconomic impacts Mia M. Bennett a,*, Scott R. Stephenson b, Kang Yang c,d,e, Michael T. Bravo f, Bert De Jonghe g a Department of Geography and School of Modern Languages & Cultures (China Studies Programme), Room 8.09, Jockey Club Tower, Centennial Campus, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong b RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA c School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China d Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210023, China e Collaborative Innovation Center for the South Sea Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China f Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK g Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT With current scientifc models forecasting an ice-free Central Arctic Ocean (CAO) in summer by mid-century and potentially earlier, a direct shipping route via the North Pole connecting markets in Asia, North America, and Europe may soon open. The Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) would represent a third Arctic shipping route in addition to the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage. In response to the continued decline of sea ice thickness and extent and growing recognition within the Arctic and global governance communities of the need to anticipate -

1617-Greenland Annular Eclipse 2021 ROLL.Indd

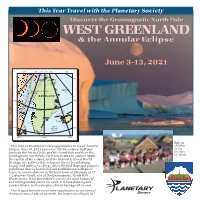

This Year Travel with the Planetary Society Discover the Geomagnetic North Pole WEST GREENLAND & the Annular Eclipse June 3-13, 2021 20°E 80°W 60°W 40°W 20°W 0° 20°E ARCTIC OCEAN CANADA1 2 20°E 0 2 , 0 1 e n u J - GREENLAND e s SEA p Qaanaaq i l c E GREENLAND 0° r a l 70°N u 70°N n BAFFIN n BAY A e h t f Arctic Circle o Disco Bay Ilulissat th a P Nuuk 60°N NORTH ATLANTIC 60°N OCEAN 40°W 40°W 20°W Ilulissat This is an extraordinary, rare opportunity to see an Annular children Eclipse, June 10, 2021, pass over NW Greenland, half way on the between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole and near the first day Geomagnetic North Pole. Fly from Iceland to explore Nuuk, of school the capital of Greenland, and the Ilulissat Icefjord World Heritage site at Disco Bay, reknown for its breathtaking beauty and miles of icebergs. Meet the sled dogs and puppies in Ilulissat. Stay in hotels in Nuuk and Ilulissat, with guest house accommodations in the Inuit town of Qaanaaq at 77 1/2 degrees North, site of the Geomagnetic North Pole Observatory. West Greenland is one of the most beautiful and unforgettable places on earth. It is breathtaking and extraordinary, with a unique cultural heritage all its own. This is quite literally a one-time opportunity to visit one of the most remote places on earth. We hope you will join us! Ilulissat & Disco Bay Itinerary Day 1/2 Depart USA for Reykjavik, Iceland Depart Newark or other IcelandAir gateway cities for Reykjavik, Iceland, arriving around 6:30 am on Day 2. -

The Polar Regions

TEACHING DOSSIER 1 ENGLISH, GEOGRAPHY, SCIENCE, ECONOMICS THE POLAR REGIONS ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, FAUNA, FLORA, CLIMATE CHANGE, THREATS, CONSERVATION NORTH POLE SOUTH POLE 2 dossier CZE N° 1 THEORY SECTION THE ARCTIC AND ANTARCTIC The Arctic and the Antarctic have a number of points in common: low temperatures, darkness that lasts for several weeks or months in winter, and magnificent expanses of ice... There are several different types of ice1, including sea ice, which is ice that contains salt, and ice caps and icebergs, which consist solely of freshwater ice. How- ever, once we get past these initial similarities, it doesn’t take long to realise that the Arctic and the Antarctic are two totally different regions. THE ARCTIC - Frozen ocean surrounded by land - North Pole: located approximately in the centre of the Arctic Ocean - Ocean covered to a large extent by permanent sea ice - Holds almost 10% of all the Earth’s continental ice (7% of the world’s reserves of freshwater) - Outer limit: place where the temperature never exceeds 10°C during the warmest month (July) - Area: 21 million km2 (14 million km2 of which is the Arctic Ocean) Ice drift Maximum extent of the sea ice in summer Maximum extent of the sea ice in winter Outer limit of the Arctic 10°C Figure 1: Outer limit of the Arctic and seasonal variation of the sea ice The Arctic Ocean is bordered by broad, shallow continental plates and consists of two main basins (4 km deep on average) separated by a range of underwater mountains: the Lomonosov Ridge, which joins the north of Greenland to the New Siberia Archipelago along a line that runs close to the North Pole.