Navigation in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

What Legal Framework Governs the North Pole?

What legal framework governs the North Pole? Master thesis International Law Tilburg University J.R. Mulder (ANR 865773) Supervisor: Dr M. Goodwin What legal framework governs the North Pole? Table of contents. page Introduction ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 Define the North Pole area North Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 5 South Pole area ----------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Comparison ----------------------------------------------------------------- 7 Conflicting claims, what is the problem? -------------------------------------------------- 8 Sovereignty ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 12 Acquisition of territory -------------------------------------------------------------- 13 Sovereignty: jurisdiction and military power ------------------------------------ 14 The legal framework on the sea UN Charter --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 15 Customary International Law ------------------------------------------------------ 15 General Principles ------------------------------------------------------------------- 16 Jurisprudence ------------------------------------------------------------------------ 17 UNCLOS ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 17 Schematic overview of zones into the sea ---------------------------------------- 21 The legal framework applied to the North Pole -

Introduction EXPLORATION and SACRIFICE: the CULTURAL

Introduction EXPLORATION AND SACRIFICE: THE CULTURAL LOGIC OF ARCTIC DISCOVERY Russell A. POTTER Reprinted from The Quest for the Northwest Passage: British Narratives of Arctic Exploration, 1576-1874, edited by Frédéric Regard, © 2013 Pickering & Chatto. The Northwest Passage in nineteenth-century Britain, 1818-1874 Although this collective work can certainly be read as a self-contained book, it may also be considered as a sequel to our first volume, also edited by Frederic Regard, The Quest for the Northwest Passage: Knowledge, Nation, Empire, 1576-1806, published in 2012 by Pickering and Chatto. That volume, dealing with early discovery missions and eighteenth-century innovations (overland expeditions, conducted mainly by men working for the Hudson’s Bay Company), was more historical, insisting in particular on the role of the Northwest Passage in Britain’s imperial project and colonial discourse. As its title indicates, this second volume deals massively with the nineteenth century. This was the period during which the Northwest Passage was finally discovered, and – perhaps more importantly – the period during which the quest reached an unprecedented level of intensity in Britain. In Sir John Barrow’s – the powerful Second Secretary to the Admiralty’s – view of Britain’s military, commercial and spiritual leadership in the world, the Arctic remained indeed the only geographical discovery worthy of the Earth’s most powerful nation. But the Passage had also come to feature an inaccessible ideal, Arctic landscapes and seascapes typifying sublime nature, in particular since Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein (1818). And yet, for all the attention lavished on the myth created by Sir John Franklin’s overland expeditions (1819-1822, 1825-18271) and above all by the one which would cost him his life (1845-1847), very little research has been carried out on the extraordinary Arctic frenzy with which the British Admiralty was seized between 1818, in the wake of the end of the Napoleonic wars, and 1859, which may be considered as the year the quest was ended. -

PECS Definitions and Rulings

POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME (PECS) ! DEFINITIONS AND RULINGS The Polar Expeditions Classification Scheme is a grading system for extended, unmotorised polar expeditions, crossings or circumnavigations, collectively referred to as Journeys. Polar regions, modes of travel, start and end points, routes and types of support are defined under the scheme and give expeditioners guidance on how to classify, promote and immortalise their journey. PECS uses three tiers of Designation to grade, label and describe polar journeys - a Label (made up of Label Elements), a Description and a MAP Code. Tiers are only an indication of information density. PECS does not discriminate between Modes of Travel. Each Mode is classified under the scheme allowing same-mode journeys to be compared while allowing for superficial cross-comparison. PECS is able to accommodate new modes of unmotorised travel as they develop without impacting on labelling or definitions. Journeys using engines or motors for propulsion, for any part of the journey, are not covered by PECS. PECS concentrates primarily on journeys of more than 400km in Antarctica, Greenland and on the Arctic Ocean however journeys in other polar areas and of less than 400km one-way linear distance that do not include the Poles or significant features on their line of travel may be classified on an informal basis under this scheme. Journeys choosing to use PECS must abide by PECS terminology. Shorter journeys should be labelled accordingly ie. Last Degree South Pole or Double Degree North Pole etc. All rulings and determinations are at the discretion of the PECS Committee. POLAR EXPEDITIONS CLASSIFICATION SCHEME "1 VER190220 CONTENTS 4. -

The Opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, Geopolitical, Environmental, and Socioeconomic Impacts

Marine Policy xxx (xxxx) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Policy journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/marpol The opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, geopolitical, environmental, and socioeconomic impacts Mia M. Bennett a,*, Scott R. Stephenson b, Kang Yang c,d,e, Michael T. Bravo f, Bert De Jonghe g a Department of Geography and School of Modern Languages & Cultures (China Studies Programme), Room 8.09, Jockey Club Tower, Centennial Campus, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong b RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA c School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China d Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210023, China e Collaborative Innovation Center for the South Sea Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China f Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK g Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT With current scientifc models forecasting an ice-free Central Arctic Ocean (CAO) in summer by mid-century and potentially earlier, a direct shipping route via the North Pole connecting markets in Asia, North America, and Europe may soon open. The Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) would represent a third Arctic shipping route in addition to the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage. In response to the continued decline of sea ice thickness and extent and growing recognition within the Arctic and global governance communities of the need to anticipate -

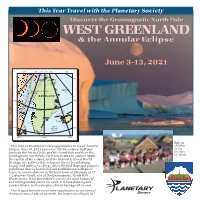

1617-Greenland Annular Eclipse 2021 ROLL.Indd

This Year Travel with the Planetary Society Discover the Geomagnetic North Pole WEST GREENLAND & the Annular Eclipse June 3-13, 2021 20°E 80°W 60°W 40°W 20°W 0° 20°E ARCTIC OCEAN CANADA1 2 20°E 0 2 , 0 1 e n u J - GREENLAND e s SEA p Qaanaaq i l c E GREENLAND 0° r a l 70°N u 70°N n BAFFIN n BAY A e h t f Arctic Circle o Disco Bay Ilulissat th a P Nuuk 60°N NORTH ATLANTIC 60°N OCEAN 40°W 40°W 20°W Ilulissat This is an extraordinary, rare opportunity to see an Annular children Eclipse, June 10, 2021, pass over NW Greenland, half way on the between the Arctic Circle and the North Pole and near the first day Geomagnetic North Pole. Fly from Iceland to explore Nuuk, of school the capital of Greenland, and the Ilulissat Icefjord World Heritage site at Disco Bay, reknown for its breathtaking beauty and miles of icebergs. Meet the sled dogs and puppies in Ilulissat. Stay in hotels in Nuuk and Ilulissat, with guest house accommodations in the Inuit town of Qaanaaq at 77 1/2 degrees North, site of the Geomagnetic North Pole Observatory. West Greenland is one of the most beautiful and unforgettable places on earth. It is breathtaking and extraordinary, with a unique cultural heritage all its own. This is quite literally a one-time opportunity to visit one of the most remote places on earth. We hope you will join us! Ilulissat & Disco Bay Itinerary Day 1/2 Depart USA for Reykjavik, Iceland Depart Newark or other IcelandAir gateway cities for Reykjavik, Iceland, arriving around 6:30 am on Day 2. -

The Polar Regions

TEACHING DOSSIER 1 ENGLISH, GEOGRAPHY, SCIENCE, ECONOMICS THE POLAR REGIONS ANTARCTIC, ARCTIC, GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, FAUNA, FLORA, CLIMATE CHANGE, THREATS, CONSERVATION NORTH POLE SOUTH POLE 2 dossier CZE N° 1 THEORY SECTION THE ARCTIC AND ANTARCTIC The Arctic and the Antarctic have a number of points in common: low temperatures, darkness that lasts for several weeks or months in winter, and magnificent expanses of ice... There are several different types of ice1, including sea ice, which is ice that contains salt, and ice caps and icebergs, which consist solely of freshwater ice. How- ever, once we get past these initial similarities, it doesn’t take long to realise that the Arctic and the Antarctic are two totally different regions. THE ARCTIC - Frozen ocean surrounded by land - North Pole: located approximately in the centre of the Arctic Ocean - Ocean covered to a large extent by permanent sea ice - Holds almost 10% of all the Earth’s continental ice (7% of the world’s reserves of freshwater) - Outer limit: place where the temperature never exceeds 10°C during the warmest month (July) - Area: 21 million km2 (14 million km2 of which is the Arctic Ocean) Ice drift Maximum extent of the sea ice in summer Maximum extent of the sea ice in winter Outer limit of the Arctic 10°C Figure 1: Outer limit of the Arctic and seasonal variation of the sea ice The Arctic Ocean is bordered by broad, shallow continental plates and consists of two main basins (4 km deep on average) separated by a range of underwater mountains: the Lomonosov Ridge, which joins the north of Greenland to the New Siberia Archipelago along a line that runs close to the North Pole. -

Antarctica: at the Heart of It All

4/8/2021 Antarctica: At the heart of it all Dr. Dan Morgan Associate Dean – College of Arts & Science Principal Senior Lecturer – Earth & Environmental Sciences Vanderbilt University Osher Lifelong Learning Institute Spring 2021 Webcams for Antarctic Stations III: “Golden Age” of Antarctic Exploration • State of the world • 1910s • 1900s • Shackleton (Nimrod) • Drygalski • Scott (Terra Nova) • Nordenskjold • Amundsen (Fram) • Bruce • Mawson • Charcot • Shackleton (Endurance) • Scott (Discovery) • Shackleton (Quest) 1 4/8/2021 Scurvy • Vitamin C deficiency • Ascorbic Acid • Makes collagen in body • Limits ability to absorb iron in blood • Low hemoglobin • Oxygen deficiency • Some animals can make own ascorbic acid, not higher primates International scientific efforts • International Polar Years • 1882-83 • 1932-33 • 1955-57 • 2007-09 2 4/8/2021 Erich von Drygalski (1865 – 1949) • Geographer and geophysicist • Led expeditions to Greenland 1891 and 1893 German National Antarctic Expedition (1901-04) • Gauss • Explore east Antarctica • Trapped in ice March 1902 – February 1903 • Hydrogen balloon flight • First evidence of larger glaciers • First ice dives to fix boat 3 4/8/2021 Dr. Nils Otto Gustaf Nordenskjold (1869 – 1928) • Geologist, geographer, professor • Patagonia, Alaska expeditions • Antarctic boat Swedish Antarctic Expedition: 1901-04 • Nordenskjold and 5 others to winter on Snow Hill Island, 1902 • Weather and magnetic observations • Antarctic goes north, maps, to return in summer (Dec. 1902 – Feb. 1903) 4 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 1 • November and December, 1902 too much ice • December 1902: Three meant put ashore at hope bay, try to sledge across ice • Can’t make it, spend winter in rock hut 5 4/8/2021 Attempts to make it to Snow Hill Island: 2 • Antarctic stuck in ice, January 1903 • Crushed and sinks, Feb. -

The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: an Historical Perspective

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State History Theses History and Social Studies Education 12-2011 The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Kayla J. Shypski [email protected] Advisor Dr. Cynthia A. Conides First Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D., Associate Professor of History and Social Studies Education, Director of Museum Studies Second Reader Lisa Marie Anselmi, Ph.D., R.P.A., Associate Professor and Chair of the Anthropology Department Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to http://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Shypski, Kayla J., "The orN th Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective" (2011). History Theses. Paper 2. Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons i ABSTRACT OF THESIS The North Pole Controversy of 1909 and the Treatment of the Greenland Inuit People: An Historical Perspective Polar exploration was a large part of American culture and society during the mid to late nineteenth century and the early twentieth century. The North Pole controversy of 1909 in which two American Arctic explorers both claimed to have reached the North Pole was a culmination of the polar exploration era. However, one aspect of the polar expeditions that is relatively unknown is the treatment of the native Inuit peoples of the Arctic by the polar explorers. -

“The Race for the North Pole” Icelandic and Nordic Security Policy in Transition Delivered on 29 August 2007 Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, Foreign Minister

“The Race for the North Pole” Icelandic and Nordic security policy in transition Delivered on 29 August 2007 Ingibjörg Sólrún Gísladóttir, Foreign Minister The final text is the speech as delivered Members of the Conference: It gave me great pleasure to accept your invitation to address the opening session of this seminar, which is held in connection with the start of the NATO - Partnership for Peace Exercise Northern Challenge 2007. Iceland’s national security and defence are now at a historic turning point. Until now, Iceland has been more or less a passive recipient in the defence co-operation of western states. For decades, the United States Defence Force assumed the role that independent sovereign states normally play themselves. In fact, the United States spoke for Iceland within NATO when it came to military matters, and in many ways they appeared in the role of Iceland’s guardian. The United States’ contribution to Iceland’s defence was of course very important, but at the same time it had the effect of isolating us from our neighbouring countries. That time is now behind us and a new period has begun in Iceland’s security and defence. Following the signature of an agreement with the United States providing for the departure of their armed forces from Iceland, efforts were begun under the leadership of the current Prime Minister to strengthen and increase our security and defence co-operation with other neighbouring countries. Discussions have been held with Norway, Denmark, the United Kingdom, Canada and Germany, to mention a few examples, and framework agreements have already been concluded with Norway and Denmark on defence co-operation. -

North Pole Exposure – Scene 1 – Kids & Citizens

NORTH POLE EXPOSURE – SCENE 1 – KIDS & CITIZENS (The citizens of the North Pole freeze in their final positions at the end of the song.) (A group of young people walk onto the stage. They are wearing winter traveling clothes and carrying suitcases, etc. They are awestruck and excited to be in this magical place.) KID 1: Wow! I can’t believe we finally made it to the North Pole! KID 2: I can’t believe it really exists! (The citizens of the North Pole giggle and try to hold their pose.) KID 3: What was that? KID 4: What was what? (more giggling) KID 3: That?! (Kid 5 is over taking a very close look at one of the stationary elves to see if it is real.) KID 5: Hey, guys! Look at this! (He touches the elf.) ELF 1: Boo! Kid 5 and all others: AHHHHHH! (All of the citizens of the North Pole start laughing and break their poses. They talk to each other, slap each other on the back and cause a general hubbub. Santa moves over to one side of the stage.) KID 6: Are they real? ELF 2: Are WE real? (sarcastically) Well, I don’t know? Are we real? What do you think, everybody? Are we real? (citizens all laugh again) MRS. CLAUS: (walking up to the kids to reassure them) Oh, now, be nice, everyone. After all, they are our guests, and it isn’t very often that we have guests way up here in the North Pole! KID 7: Wow! It’s Mrs. -

1 TITLE: World According to Dicæarchus DATE: 300 BC AUTHOR

World view according to Dicæarchus #111 TITLE: World according to Dicæarchus DATE: 300 B.C. AUTHOR: Dicæarchus of Messana DESCRIPTION: Pytheas (ca. 320-305), a contemporary of Alexander the Great, is significant for extending geographic knowledge of Western Europe, especially the coasts along the English Channel, and for his use of astronomical observations to compute latitudes. A navigator and astronomer from the Greek colony of Massalia [Marseilles], he explored the Ocean west of the European mainland and recorded his journey and observations in the work entitled On the Ocean, now lost but quoted and criticized by Strabo. Pytheas’ claim to have explored “in person” the entire northern region of Europe “as far as the ends of the world” met with disbelief by Strabo who accused him of shameless mendacity. Nonetheless, other writers used his observations. Most modern scholars agree that his journey in fact occurred, yet there is no consensus regarding its date or time or scope—perhaps reaching to islands north of Scotland, to Norway, to Jutland, or even to Iceland. Pytheas sailed from Massalia through the Pillars of Hercules {Straits of Gibraltar] up the Iberian coast to the Tin Islands (Cassiterges, whose location is contested) and across to Britain; next probably the coast to Scotland, its Northern Isles, and the island of Thule; then back east to the Baltic, where he found the source of amber on the island of Abalus. He described Britain as a triangle, and with reasonable accuracy he estimated the island’s circumference at more than 40,000 stadia, a length considered excessive by Strabo but accepted by Eratosthenes.