University of Copenhagen Department of Media, Cognition and Commu Nication

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

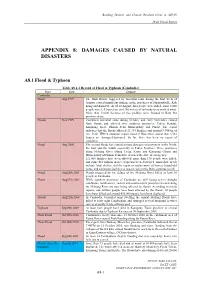

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Words: Corner Beam-Column Joint; Hysteresis Loops; Seismic Design; Ductility; Stiffness; Equivalent Viscous Damping

Journal of Mechanical Engineering Vol 16(1), 213-226, 2019 Validation of Corner Beam-column Joint’s Hysteresis Loops between Experimental and Modelled using HYSTERES Program N.F. Hadi, M. Mohamad Faculty of Civil Engineering, Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia N.H. Hamid Institute of Infrastructure Engineering Sustainability and Management Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia ABSTRACT The beam - column joint is an important part of a multi-storey RC building as it caters for lateral and gravitational load during an earthquake event. The beam-column joints should have a medium to high ductility for transferring the earthquake load and gravity load to the foundation. By designing multi- storey RC buildings using Eurocode 8 can avoid any diagonal shear cracks in column which is a major problem in non-seismic design buildings using British Standard (BS8110). This paper presents the experimental hysteresis loops of monolithic corner beam-column joints of multi-storey building which had been designed using Eurocode 8 and tested under in-plane lateral cyclic loading. The experimental hysteresis loops of corner beam-column joint was compared with modelled using the HYSTERES program. The full-scale corner beam- column joint of a two story precast school building was designed, constructed, tested and modelled is presented herein. The seismic performance parameters such as lateral strength capacity, stiffness, ductility and equivalent viscous damping were compared between experimental and modelled hysteresis loops. The experimental hysteresis loops have similar shape with the modeling hysteresis loops with small percentage differences between them. Keywords: Corner beam-column joint; hysteresis loops; seismic design; ductility; stiffness; equivalent viscous damping ___________________ ISSN 1823-5514, eISSN2550-164X Received for review: 2017-07-10 © 2016 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Accepted for publication: 2018-05-18 Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Malaysia. -

Natural Disasters 48

ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER THREAT ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER 2020 2020 UNDERSTANDING ECOLOGICAL THREATS, RESILIENCE AND PEACE Institute for Economics & Peace Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City, Brussels and Harare. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Ecological Threat Register 2020: Understanding Ecological Threats, Resilience and Peace, Sydney, September 2020. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). SPECIAL THANKS to Mercy Corps, the Stimson Center, UN75, GCSP and the Institute for Climate and Peace for their cooperation in the launch, PR and marketing activities of the Ecological Threat Register. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings -

Cover 2Nd Asean Env Report 2000

SecondSecond ASEANASEAN State State ofof thethe EnvironmentEnvironment ReportReport 20002000 Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 Our Heritage Our Future Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 Published by the ASEAN Secretariat For information on publications, contact: Public Information Unit, The ASEAN Secretariat 70 A Jalan Sisingamangaraja, Jakarta 12110, Indonesia Phone: (6221) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (6221) 739-8234, 724-3504 ASEAN website: http://www.aseansec.org The preparation of the Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 was supervised and co- ordinated by the ASEAN Secretariat. The following focal agencies co-ordinated national inputs from the respective ASEAN member countries: Ministry of Development, Negara Brunei Darussalam; Ministry of Environment, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia; Ministry of State for Environment, Republic of Indonesia; Science, Technology and Environment Agency, Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Ministry of Science Technology and the Environment, Malaysia; National Commission for Environmental Affairs, Union of Myanmar; Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Republic of the Philippines; Ministry of Environment, Republic of Singapore; Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, Royal Kingdom of Thailand; and Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat wishes to express its sincere appreciation to UNEP for the generous financial support provided for the preparation of this Report. The ASEAN Secretariat also wishes to express its sincere appreciation to the experts, officials, institutions and numerous individuals who contributed to the preparation of the Report. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, and to fully acknowledge all sources of information, graphics and photographs used in the Report. -

Effect of Fine Content on Soil Dynamic Properties

Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol. 13, No. 4 (2018) 851 - 861 © School of Engineering, Taylor’s University EFFECT OF FINE CONTENT ON SOIL DYNAMIC PROPERTIES J. X. LIM, M. L. LEE*, Y. TANAKA Department of Civil Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, 43000, Kajang, Selangor DE, Malaysia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Dynamic properties of soil have attracted an increasing attention among geotechnical engineers in Malaysia owing to the frequent earthquake incidents reported recently and the demand of high speed railway infrastructures. The present study investigated the effect of fine content on the soil dynamic properties based on three selected soils in Malaysia. One sand mining trail (i.e. silty sand) and two tropical residual soils (i.e. sandy clay and sandy silt) were tested on a 1 g shaking table. The experimental shear moduli were compared with the established degradation curves of sandy and clayey soils obtained from literature. The shear moduli attenuated with the increase of shear strain amplitude for the three soil samples. The amount of fine content in the soil was found to be a more dominant factor affecting the dynamic properties of soil compared with the plasticity and geological characteristics of the soil. The experimental shear moduli of sandy silt were similar to that of sandy clay. It may be attributed to the fact that the two studied residual soils have a similar amount of fine content. In addition, the shear moduli of the studied residual soils could not be fitted to the degradation curves of sand and clay which have been well studied in the past. -

DISASTER RISK MAPPING and ASSESSMENT (GEORISK 2019) 25-27 February 2019 @ KBN, KUNDASANG, SABAH

WORKSHOP & FORUM ON GEOSPATIAL TECHNOLOGY FOR DISASTER RISK MAPPING AND ASSESSMENT (GEORISK 2019) 25-27 February 2019 @ KBN, KUNDASANG, SABAH THEME: ADVANCING SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION Workshop & Forum on Geospatial DATE: Technology for Disaster Risk Mapping and 25- 27 FEBRUARY 2019 Assessment (GeoRisk2019) aims to provide an insight into modern and advanced geospatial technology fo r mapping, VENUE: analysing and assessing multi-geohazard KBN KUNDASANG,SABAH and disaster risk in a complex environment. Organized by Global and regional ca s e studies, covering Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) Kuala Lumpur several benchmarking and best practices will be interactively discussed. This co u rs e With the support of Department of Minerals and Geoscience Malaysia (JMG) addresses the importance of Department of Surveying and Mapping Malaysia (JUPEM) understanding georisk, strengthening risk Sabah Lands and Surveys Department (JTU) governance and elevating disaster Royal Institution of Surveyors Malaysia (RISM) preparedness. New, cutting-edge mapping Society for Engineering Geology and Rock Mechanics (SEGRM) technology (UAV, Terrestrial laser scanning, LiDAR, GNSS, Remote Sensing) coupling Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Japan with BigData Analytics, early-warning Japan-ASEAN Science, Technology and Innovative Platform system, monitoring system and predictive Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction WG, modelling will be shared. Ad va n ced earth Global Young Academy (GYA) observation and geospatial data are highly International Council for Science (ISC)ROAP in demand fo r disaster mitigation, prevention, risk assessment and reduction strategies in a changing climate. GeoRisk2019 promotes an intelligent, integrated and transdisciplinary approach for reducing disaster risk, as in line with the Fee: RM800/person - 3 Days 2 nights Sendai Framework fo r Disaster Risk • Inclusive airport transfer (only limited pick-up time); accommodation @ KBN Ku nd a sa n g; daily Reduction 2015-2030 and national policies. -

The Case of Floods’, in Sawada, Y

Chapter 14 Impacts of Disasters and Disasters Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods Ngai Weng Chan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia December 2012 This chapter should be cited as Chan, N. W. (2012), ‘Impacts of Disasters and Disasters Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods’, in Sawada, Y. and S. Oum (eds.), Economic and Welfare Impacts of Disasters in East Asia and Policy Responses. ERIA Research Project Report 2011-8, Jakarta: ERIA. pp.503-551. CHAPTER 14 Impacts of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods NGAI WENG CHAN* Universiti Sains Malaysia Malaysia lies in a geographically stable region, relatively free from natural disasters, but is affected by flooding, landslides, haze and other man-made disasters. Annually, flood disasters account for significant losses, both tangible and intangible. Disaster management in Malaysia is traditionally almost entirely based on a government-centric top-down approach. The National Security Council (NSC), under the Prime Minister’s Office, is responsible for policies and the National Disaster Management and Relief Committee (NDMRC) is responsible for coordinating all relief operations before, during and after a disaster. The NDMRC has equivalent organizations at the state, district and “mukim” (sub-district) levels. In terms of floods, the NDMRC would take the form of the National Flood Disaster Relief and Preparedness Committee (NFDRPC). Its main task is to ensure that assistance and aid are provided to flood victims in an orderly and effective manner from the national level downwards. Its approach is largely reactive to flood disasters. The NFDRPC is activated via a National Flood Disaster Management Mechanism (NFDMM). -

Appendix 3 Selection of Candidate Cities for Demonstration Project

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report APPENDIX 3 SELECTION OF CANDIDATE CITIES FOR DEMONSTRATION PROJECT Table A3-1 Long List Cities (No.1-No.62: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-1 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-2 Long List Cities (No.63-No.124: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-2 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-3 Long List Cities (No.125-No.186: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-3 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-4 Long List Cities (No.187-No.248: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-4 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-5 Long List Cities (No.249-No.310: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. EIGHT-JAPAN ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS INC. A3-5 Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Final Report Table A3-6 Long List Cities (No.311-No.372: “abc” city name order) Source: JICA Project Team NIPPON KOEI CO.,LTD. PAC ET C ORP. -

Mindanao Spatial Strategy/Development Framework (Mss/Df) 2015-2045

National Economic and Development Authority MINDANAO SPATIAL STRATEGY/DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (MSS/DF) 2015-2045 NEDA Board - Regional Development Committee Mindanao Area Committee ii MINDANAO SPATIAL STRATEGY/DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (MSS/DF) MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRPERSON For several decades, Mindanao has faced challenges on persistent and pervasive poverty, as well as chronic threats to peace. Fortunately, it has shown a considerable amount of resiliency. Given this backdrop, an integrative framework has been identified as one strategic intervention for Mindanao to achieve and sustain inclusive growth and peace. It is in this context that the role of the NEDA Board-Regional Development Committee-Mindanao becomes crucial and most relevant in the realization of inclusive growth and peace in Mindanao, that has been elusive in the past. I commend the efforts of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) for initiating the formulation of an Area Spatial Development Framework such as the Mindanao Spatial Strategy/Development Framework (MSS/DF), 2015-2045, that provides the direction that Mindanao shall take, in a more spatially-defined manner, that would accelerate the physical and economic integration and transformation of the island, toward inclusive growth and peace. It does not offer “short-cut solutions” to challenges being faced by Mindanao, but rather, it provides guidance on how Mindanao can strategically harness its potentials and take advantage of opportunities, both internal and external, to sustain its growth. During the formulation and legitimization of this document, the RDCom-Mindanao Area Committee (MAC) did not leave any stone unturned as it made sure that all Mindanao Regions, including the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), have been extensively consulted as evidenced by the endorsements of the respective Regional Development Councils (RDCs)/Regional Economic Development and Planning Board (REDPB) of the ARMM. -

Riches at the Base of the Pyramid Alleviating Poverty with Green Productivity and Sustainability

The Asian Productivity Organization (APO) is an intergovernmental organization committed to improving productivity in the Asia- Pacific region. Established in 1961, the APO contributes to the sustainable socioeconomic development of the region through policy advisory services, acting as a think tank, and undertaking smart initiatives in the industry, agriculture, service, and public sectors. The APO is shaping the future of the region by assisting member economies in formulating national strategies for enhanced productivity and through a range of institutional capacity building efforts, including research and centers of excellence in member countries. APO members Bangladesh, Cambodia, Republic of China, Fiji, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Islamic Republic of Iran, Japan, Republic of Korea, Lao PDR, Malaysia, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Vietnam. RICHES AT THE BASE OF THE PYRAMID ALLEVIATING POVERTY WITH GREEN PRODUCTIVITY AND SUSTAINABILITY OCTOBER 2019 | ASIAN PRODUCTIVITY ORGANIZATION Riches at the Base of the Pyramid Alleviating poverty with green productivity and sustainability Prof. Allen H. Hu served as the volume editor. First edition published in Japan by the Asian Productivity Organization 1-24-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku Tokyo 113-0033, Japan www.apo-tokyo.org © 2019 Asian Productivity Organization The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Asian Productivity Organization (APO) or any APO member. All rights reserved. None of the contents of this publication may be used, reproduced, stored, or transferred in any form or by any means for commercial purposes without prior written permission from the APO. Designed by Convert To Curves Media Private Limited CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES V LIST OF FIGURES VI FOREWORD IX PREAMBLE XI CHAPTER 1. -

Geospatial Approach for Landslide Activity Assessment and Mapping Based on Vegetation Anomalies

The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Volume XLII-4/W9, 2018 International Conference on Geomatics and Geospatial Technology (GGT 2018), 3–5 September 2018, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia GEOSPATIAL APPROACH FOR LANDSLIDE ACTIVITY ASSESSMENT AND MAPPING BASED ON VEGETATION ANOMALIES Mohd Radhie Mohd Salleh1, Nurliyana Izzati Ishak1, Khamarrul Azahari Razak2, Muhammad Zulkarnain Abd Rahman1*, Mohd Asraff Asmadi1, Zamri Ismail1, Mohd Faisal Abdul Khanan1 1 Faculty of Built Environment and Surveying, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor, Malaysia - [email protected] 2 UTM Razak School of Engineering and Advanced Technology, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur KEY WORDS: Tropical rain forest, Landslide activity, Vegetation anomalies ABSTRACT: Remote sensing has been widely used for landslide inventory mapping and monitoring. Landslide activity is one of the important parameters for landslide inventory and it can be strongly related to vegetation anomalies. Previous studies have shown that remotely sensed data can be used to obtain detailed vegetation characteristics at various scales and condition. However, only few studies of utilizing vegetation characteristics anomalies as a bio-indicator for landslide activity in tropical area. This study introduces a method that utilizes vegetation anomalies extracted using remote sensing data as a bio-indicator for landslide activity analysis and mapping. A high-density airborne LiDAR, aerial photo and satellite imagery were captured over the landslide prone area along Mesilau River in Kundasang, Sabah. Remote sensing data used in characterizing vegetation into several classes of height, density, types and structure in a tectonically active region along with vegetation indices. About 13 vegetation anomalies were derived from remotely sensed data.