Cover 2Nd Asean Env Report 2000

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

English After School Hours (HL) (NST 24/10/2002)

24/10/2002 English after school hours (HL) Joniston Bangkuai; Chow Kum Hor KUALA LUMPUR, Wed. - MCA president Datuk Seri Dr Ling Liong Sik claimed today that Chinese-based parties in the Barisan Nasional were proposing that national-type Chinese schools be exempted from the teaching of Science and Mathematics in English during normal school hours. Dr Ling said the Chinese-based parties in BN would propose that Science and Mathematics be taught in English outside normal schooling hours for national-type Chinese primary schools. However, he said the use of Mandarin to teach the subjects during the normal timetable should be retained. Dr Ling said the proposal was brought up during yesterday's BN supreme council meeting and the Chinese-based parties had asked for one week to fine-tune the proposal. Dr Ling's statement coincided with Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad saying that reforming Malaysia's education system and taking steps to preserve the country's fragile multi-racial peace were his top priorities before stepping down next October. Dr Mahathir, speaking to foreign journalists at his Putrajaya office yesterday as reported by the Singapore Straits Times, said one of his pressing concerns was education reform, namely pushing through his proposal to introduce English as a medium of instruction for Mathematics and Science in primary schools from January. Although the proposal had drawn fire from some groups within the ruling coalition, he was undeterred and asserted that like the rest of the world, Malaysia would have "to go with the times" and promote the use of English. -

Penyata Rasmi Parlimen Parliamentary Debates

JilidIV Hari Rabu Bil.14 14hb Disember, 1994 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN NEGARA Senate PARLIMEN KELAPAN Eighth Parliament PENGGAL KEEMPAT Fourth Session KAND UN GAN MENGANGKAT SUMPAH: Y.B. Tan Sri Dato' Vadiveloo a/I Govindasamy [Ruangan 1929] Y.B. Dato' Johan B.0.T. Ghani [Ruangan 1930] Y.B. Tuan Rahim bin Baba Y.B. Tuan Ding Seling Y.B. Dato' V.K.K. Teagarajan Y.B. Tuan Chong Kah Kiat Y.B. Puan Mastika Junaidah binti Husin Y.B. Tuan Tan Son Lee Y.B. Tuan Low Kai Meng PEMILIHAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA DEWAN NEGARA MENGIKUT PERKARA 56 PERLEMBAGAAN PERSEKUTUAN [Ruangan 1929] UCAPAN TERIMA KASIH DAN PENGHARGAAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA DEWAN NEGARA [Ruangan 1930] MENGANGKAT SUMPAH DI LUAR DEWAN: - Y.B. Datuk Dr. Jeffrey G. Kitingan Y.B. Tuan Haji Zainal bin Md. Deros Y.B. Tuan M. Zeevill @ Shanmugam a/I R.M.S. Mutaya [Ruangan 1931] PEMILIHAN TIMBALAN YANG DI-PERTUA DEWAN NEGARA [Ruangan 1931] PEMASYHURAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA: Mengalu-alukan Ahli-abli Baru [Ruangan 1931] Memperkenankan Akta-akta [Ruangan 1932] Perutusan daripada Dewan Rakyat [Ruangan 1933] URUSAN MESYUARA T [Ruangan 1933] JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 1934] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Perbekalan Tambahan (1994) (No. 2) 1994 [Ruangan 1975] MALAYSIA DEWAN NEGARA PARLIMEN KELAPAN Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG KEEMPAT AHLI-AHLI DEWAN NEGARA Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Penua, TAN Slll DATO' G. VADNELOO A/L GoVINDASAMY, P.S.M., D.P.M.S., S.M.S., A.M.N. (Dilantik). Menteri Pembangunan Luar Bandar, DATO' HAJI ANNuAR BIN MusA, " SJ.M.P. -

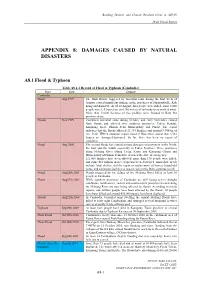

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

PLACE and INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised Page Numbers Refer to Extended Entries

PLACE AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZA TIONS INDEX Italicised page numbers refer to extended entries Aachcn, 549, 564 Aegean North Region. Aktyubinsk, 782 Alexandroupolis, 588 Aalborg, 420, 429 587 Akure,988 Algarve. 1056, 1061 Aalst,203 Aegean South Region, Akureyri, 633, 637 Algeciras, I 177 Aargau, 1218, 1221, 1224 587 Akwa Ibom, 988 Algeria, 8,49,58,63-4. Aba,988 Aetolia and Acarnania. Akyab,261 79-84.890 Abaco,178 587 Alabama, 1392, 1397, Al Ghwayriyah, 1066 Abadan,716-17 Mar, 476 1400, 1404, 1424. Algiers, 79-81, 83 Abaiang, 792 A(ghanistan, 7, 54, 69-72 1438-41 AI-Hillah,723 Abakan, 1094 Myonkarahisar, 1261 Alagoas, 237 AI-Hoceima, 923, 925 Abancay, 1035 Agadez, 983, 985 AI Ain. 1287-8 Alhucemas, 1177 Abariringa,792 Agadir,923-5 AlaJuela, 386, 388 Alicante, 1177, 1185 AbaslUman, 417 Agalega Island, 896 Alamagan, 1565 Alice Springs, 120. Abbotsford (Canada), Aga"a, 1563 AI-Amarah,723 129-31 297,300 Agartala, 656, 658. 696-7 Alamosa (Colo.). 1454 Aligarh, 641, 652, 693 Abecbe, 337, 339 Agatti,706 AI-Anbar,723 Ali-Sabieh,434 Abemama, 792 AgboviIle,390 Aland, 485, 487 Al Jadida, 924 Abengourou, 390 Aghios Nikolaos, 587 Alandur,694 AI-Jaza'ir see Algiers Abeokuta, 988 Agigea, 1075 Alania, 1079,1096 Al Jumayliyah, 1066 Aberdeen (SD.), 1539-40 Agin-Buryat, 1079. 1098 Alappuzha (Aleppy), 676 AI-Kamishli AirpoI1, Aberdeen (UK), 1294, Aginskoe, 1098 AI Arish, 451 1229 1296, 1317, 1320. Agion Oras. 588 Alasb, 1390, 1392, AI Khari]a, 451 1325, 1344 Agnibilekrou,390 1395,1397,14(K), AI-Khour, 1066 Aberdeenshire, 1294 Agra, 641, 669, 699 1404-6,1408,1432, Al Khums, 839, 841 Aberystwyth, 1343 Agri,1261 1441-4 Alkmaar, 946 Abia,988 Agrihan, 1565 al-Asnam, 81 AI-Kut,723 Abidjan, 390-4 Aguascalientes, 9(X)-1 Alava, 1176-7 AlIahabad, 641, 647, 656. -

Words: Corner Beam-Column Joint; Hysteresis Loops; Seismic Design; Ductility; Stiffness; Equivalent Viscous Damping

Journal of Mechanical Engineering Vol 16(1), 213-226, 2019 Validation of Corner Beam-column Joint’s Hysteresis Loops between Experimental and Modelled using HYSTERES Program N.F. Hadi, M. Mohamad Faculty of Civil Engineering, Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia N.H. Hamid Institute of Infrastructure Engineering Sustainability and Management Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia ABSTRACT The beam - column joint is an important part of a multi-storey RC building as it caters for lateral and gravitational load during an earthquake event. The beam-column joints should have a medium to high ductility for transferring the earthquake load and gravity load to the foundation. By designing multi- storey RC buildings using Eurocode 8 can avoid any diagonal shear cracks in column which is a major problem in non-seismic design buildings using British Standard (BS8110). This paper presents the experimental hysteresis loops of monolithic corner beam-column joints of multi-storey building which had been designed using Eurocode 8 and tested under in-plane lateral cyclic loading. The experimental hysteresis loops of corner beam-column joint was compared with modelled using the HYSTERES program. The full-scale corner beam- column joint of a two story precast school building was designed, constructed, tested and modelled is presented herein. The seismic performance parameters such as lateral strength capacity, stiffness, ductility and equivalent viscous damping were compared between experimental and modelled hysteresis loops. The experimental hysteresis loops have similar shape with the modeling hysteresis loops with small percentage differences between them. Keywords: Corner beam-column joint; hysteresis loops; seismic design; ductility; stiffness; equivalent viscous damping ___________________ ISSN 1823-5514, eISSN2550-164X Received for review: 2017-07-10 © 2016 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Accepted for publication: 2018-05-18 Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Malaysia. -

List of Ministers, Deputy Ministers and Parliamentary Secretaries

09 JAN 1999 LIST OF MINISTERS, DEPUTY MINISTERS AND PARLIAMENTARY SECRETARIES: Prime Minister: Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad Deputy Prime Minister: Datuk Seri Abdullah Haji Ahmad Badawi Minister of Special Functions: Tun Daim Zainuddin Ministers in the Prime Minister's Department: Datuk Abdul Hamid Othman Datuk Tajol Rosli Ghazali Datuk Chong Kah Kiat Datuk Dr Siti Zaharah Sulaiman Deputy Minkster: Datuk Ibrahim Ali Deputy Minister: Datuk Fauzi Abdul Rahman Deputy Minister: Datuk Othman Abdul Parliamentary Secretary: Datuk Mohamed Abdullah Minister of Finance: Tun Daim Zainuddin Second Finance Minister: Datuk Mustapa Mohamed Deputy Minister: Datuk Mohamed Nazri Abdul Aziz Deputy Minister: Datuk Wong See Wah Parliamentary Secretary: Datuk Dr Shafie Mohd Salleh Minister of Human Resources: Datuk Lim Ah Lek Deputy Minister: Datuk Dr Affifuddin Omar Minister of Home Affairs: Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi Deputy Minister: Datuk Abdul Kadir Sheikh Fadzir Deputy Minister: Datuk Ong Ka Ting Foreign Minister: Datuk Seri Syed Hamid Albar Deputy Minister: Datuk Dr Leo Michael Toyad Defence Minister: Datuk Abang Abu Bakar Mustapha Deputy Minister: Datuk Dr Abdullah Fadzil Che Wan Minister of Health: Datuk Chua Jui Meng Deputy Minister: Datuk Wira Ali Rustam Parliamentary Secretary: Datuk M Mahalingam Transport Minister: Datuk Seri Dr Ling Liong Sik Deputy Minister: Datuk Ibrahim Saad Parliamentary Secretary: Datuk Chor Chee Heung Minister of Youth and Sports: Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin Deputy Minister: Datuk Loke Yuen Yow Parliamentary Secretary: -

Natural Disasters 48

ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER THREAT ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER 2020 2020 UNDERSTANDING ECOLOGICAL THREATS, RESILIENCE AND PEACE Institute for Economics & Peace Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City, Brussels and Harare. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Ecological Threat Register 2020: Understanding Ecological Threats, Resilience and Peace, Sydney, September 2020. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). SPECIAL THANKS to Mercy Corps, the Stimson Center, UN75, GCSP and the Institute for Climate and Peace for their cooperation in the launch, PR and marketing activities of the Ecological Threat Register. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings -

Effect of Fine Content on Soil Dynamic Properties

Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol. 13, No. 4 (2018) 851 - 861 © School of Engineering, Taylor’s University EFFECT OF FINE CONTENT ON SOIL DYNAMIC PROPERTIES J. X. LIM, M. L. LEE*, Y. TANAKA Department of Civil Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, 43000, Kajang, Selangor DE, Malaysia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Dynamic properties of soil have attracted an increasing attention among geotechnical engineers in Malaysia owing to the frequent earthquake incidents reported recently and the demand of high speed railway infrastructures. The present study investigated the effect of fine content on the soil dynamic properties based on three selected soils in Malaysia. One sand mining trail (i.e. silty sand) and two tropical residual soils (i.e. sandy clay and sandy silt) were tested on a 1 g shaking table. The experimental shear moduli were compared with the established degradation curves of sandy and clayey soils obtained from literature. The shear moduli attenuated with the increase of shear strain amplitude for the three soil samples. The amount of fine content in the soil was found to be a more dominant factor affecting the dynamic properties of soil compared with the plasticity and geological characteristics of the soil. The experimental shear moduli of sandy silt were similar to that of sandy clay. It may be attributed to the fact that the two studied residual soils have a similar amount of fine content. In addition, the shear moduli of the studied residual soils could not be fitted to the degradation curves of sand and clay which have been well studied in the past. -

In This Issue: 63Rd Merdeka Approaching Sabah State Still in Search of a Malaysian Elections Identity

Aug 2020 No. 6 advisoryIMAN Research In this issue: 63rd Merdeka Approaching Sabah State Still in Search of A Malaysian Elections Identity Photo credit: Deva Darshan Based in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, IMAN Research (legally registered as PanjiAlam Centre Sdn Bhd) is a think tank which focuses on security and socio-political matters. IMAN Research is spearheaded by experts with extensive local and international experience in the areas of management consultancy, social policy development, community resilience and engagement, particularly in the area of security, electoral reform, participatory urban redevelopment and psycho-social intervention within communities in conflict. We concentrate in the domains of peace and security, ethnic relations and religious harmony. We aim to deliver sound policy solutions along with implementable action plans with measurable outcomes. To date, we have worked with Malaysian and foreign governments as well as the private sectors and international bodies, such as Google, UNICEF, UNDP and USAID, on issues ranging from security, elections to civil society empowerment. www.imanresearch.com editorial letter We are entering an exciting month, September: Sabah will hold state elections on September In this issue: 26, 2020, and Sabahans and Malaysians are looking at the elections with great eagerness. Last month itself saw Musa Aman, the former 63rd Merdeka: Sabah Chief Minister, disputing the dissolution Still in Search of A of state legislative assembly by the incumbent 1 Chief Minister and subsequently filing a Malaysian Identity lawsuit against the state’s Governor, TYT Juhar Mahiruddin, and to his shock, failed. In fact, this year itself saw Malaysians reeling Approaching Sabah State from so many political upheavals, even during the MCO when Covid 19 hit the whole world, 2 Elections that we are fed up. -

Dewan Negara

Bil. 16 Isnin 3 Ogos 1998 MALAYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN DEWAN NEGARA PARLIMEN KESEMBILAN PENGGAL KEEMPAT MESYUARAT KEDUA KANDUNGAN PEMASYHURAN TUAN YANG DI-PERTUA - Memperkenankan Akta-akta (Ruangan 1) - Perutusan Daripada Dewan Rakyat (Ruangan 1) URUSAN MESYUARAT (Ruangan2) UCAPAN TAKZIAH: Ucapan Takziah Kepada Keluarga Mendiang Tuan Jinuin bin Jimin dan Keluarga Allahyarham Dato' Zainol Abidin binJohari (Ruangan2) JAWAPAN-JA W APAN LISAN BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN (Ruangan3) RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Ahli Kimia (Pindaan) 1998 (Ruangan 16) Rang Undang-undang Pengurusan Danaharta Nasional Berhad 1998. (Ruangan 27) Ditc:rbitOleh: CAWANGAN OOKUMENTASI PARLIMEN MALAYSIA 1999 DN.3.8.1998 AHLI-AHLI DEWAN NEGARA Yang Berhonnat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, Tan Sri Dato' Haji Mohamed bin Ya'acob, P.S.M., P.M.K., S.P.M.K., Dato' Bentara Kanan, S.M.T., P.G.D.K., D.A. (Dilantik) " Menteri di Jabatan Perdana Menteri, Datuk Chong Kah Kiat, P.G.D.K., J.S.M., J.P. (Dilantik) Menteri Tanah dan Pembangunan Koperasi, Tan Sri Datuk Kasitah bin Gaddam, P.G.D.K., P.S.M., J.S.M. (Dilantik) " Timbalan Yang di-Pertua, Dato' Michael Chen Wing Sum (Dilantik) " Tuan Abdillah bin Abdul Rahim (Sarawak) " Dato' Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman (Dilantik) " Datuk Haji Abdul Majid bin Haji Baba, P.B.M., B.K.T., J.P. (Melaka) Tuan Haji Abdul Wahid bin Varthan Syed Ghany (Dilantik) " Tuan Haji Abu Bakar bin Haji Ismail, A.M.P. (Perlis) " Dato' Haji Ahmad bin Ismail (Pulau Pinang) " Tuan Haji Bakri bin Haji Ali Mahamad, A.M.N., A.M.K., B.K.M. -

A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2020 Special Issue 2020

A REVIEW OF MEDIA COVERAGE OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND GLOBAL WARMING IN 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 MeCCO monitors 120 sources (across newspapers, radio and TV) in 54 countries in seven different regions around the world. MeCCO assembles the data by accessing archives through the Lexis Nexis, Proquest and Factiva databases via the University of Colorado libraries. Media and Climate Change Observatory, University of Colorado Boulder http://mecco.colorado.edu Media and Climate Change Observatory, University of Colorado Boulder 1 MeCCO SPECIAL ISSUE 2020 A Review of Media Coverage of Climate Change and Global Warming in 2020 At the global level, 2020 media attention dropped 23% from 2019. Nonetheless, this level of coverage was still up 34% compared to 2018, 41% higher than 2017, 38% higher than 2016 and still 24% up from 2015. In fact, 2020 ranks second in terms of the amount of coverage of climate change or global warming (behind 2019) since our monitoring began 17 years ago in 2004. Canadian print media coverage – The Toronto Star, National Post and Globe and Mail – and United Kingdom (UK) print media coverage – The Daily Mail & Mail on Sunday, The Guardian & Observer, The Sun & Sunday Sun, The Telegraph & Sunday Telegraph, The Daily Mirror & Sunday Mirror, and The Times & Sunday Times – reached all-time highs in 2020. has been As the year 2020 has drawn to a close, new another vocabularies have pervaded the centers of critical year our consciousness: ‘flattening the curve’, in which systemic racism, ‘pods’, hydroxycholoroquine, 2020climate change and global warming fought ‘social distancing’, quarantines, ‘remote for media attention amid competing interests learning’, essential and front-line workers, in other stories, events and issues around the ‘superspreaders’, P.P.E., ‘doomscrolling’, and globe.