The Case of Floods’, in Sawada, Y

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cruising Guide to the Philippines

Cruising Guide to the Philippines For Yachtsmen By Conant M. Webb Draft of 06/16/09 Webb - Cruising Guide to the Phillippines Page 2 INTRODUCTION The Philippines is the second largest archipelago in the world after Indonesia, with around 7,000 islands. Relatively few yachts cruise here, but there seem to be more every year. In most areas it is still rare to run across another yacht. There are pristine coral reefs, turquoise bays and snug anchorages, as well as more metropolitan delights. The Filipino people are very friendly and sometimes embarrassingly hospitable. Their culture is a unique mixture of indigenous, Spanish, Asian and American. Philippine charts are inexpensive and reasonably good. English is widely (although not universally) spoken. The cost of living is very reasonable. This book is intended to meet the particular needs of the cruising yachtsman with a boat in the 10-20 meter range. It supplements (but is not intended to replace) conventional navigational materials, a discussion of which can be found below on page 16. I have tried to make this book accurate, but responsibility for the safety of your vessel and its crew must remain yours alone. CONVENTIONS IN THIS BOOK Coordinates are given for various features to help you find them on a chart, not for uncritical use with GPS. In most cases the position is approximate, and is only given to the nearest whole minute. Where coordinates are expressed more exactly, in decimal minutes or minutes and seconds, the relevant chart is mentioned or WGS 84 is the datum used. See the References section (page 157) for specific details of the chart edition used. -

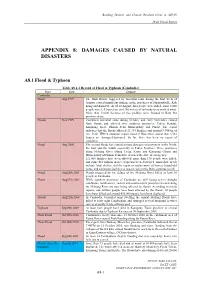

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Community Preparation and Vulnerability Indices for Floods in Pahang State of Malaysia

land Article Community Preparation and Vulnerability Indices for Floods in Pahang State of Malaysia Alias Nurul Ashikin 1 , Mohd Idris Nor Diana 1,* , Chamhuri Siwar 1, Md. Mahmudul Alam 2 and Muhamad Yasar 3 1 Institute for Environment and Development (LESTARI), Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, UKM Bangi, Bangi 43600, Malaysia; [email protected] (A.N.A.); [email protected] (C.S.) 2 School of Economics, Finance and Banking, Universiti Utara Malaysia, Sintok 06010, Malaysia; [email protected] 3 Department of Agricultural Engineering, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Syiah Kuala, Banda Aceh 23111, Indonesia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +60-3-89217657 Abstract: The east coast of Malaysia is frequently hit by monsoon floods every year that severely impact people, particularly those living close to the river bank, which is considered to be the most vulnerable and high-risk areas. We aim to determine the most vulnerable area and understand affected residents of this community who are living in the most sensitive areas caused by flooding events in districts of Temerloh, Pekan, and Kuantan, Pahang. This study involved collecting data for vulnerability index components. A field survey and face-to-face interviews with 602 respondents were conducted 6 months after the floods by using a questionnaire evaluation based on the livelihood vulnerability index (LVI). The findings show that residents in the Temerloh district are at higher risk of flooding damage compared to those living in Pekan and Kuantan. Meanwhile, the contribution factor of LVI-Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) showed that Kuantan is more Citation: Nurul Ashikin, A.; Nor exposed to the impact of climate change, followed by Temerloh and Pekan. -

Flood Impacts Across Scales: Towards an Integrated Multi-Scale Approach for Malaysia

Flood Impacts Across Scales: towards an integrated multi-scale approach for Malaysia Victoria Bell1,a, Balqis Rehan2, Bakti Hasan-Basri4, Helen Houghton-Carr1, James Miller1, Nick Reynard1, Paul Sayers5, ElizaBeth Stewart1, Mohd Ekhwan Toriman2, Badronnisa YusuF2, Zed Zulkafli2, Sam Carr5, Rhian Chapman1, Helen Davies1, Eva Fatdillah2, Matt Horritt5, ShaBir KaBirzad2, Alexandra Kaelin1, Tochukwu Okeke2, PonnamBalam Rameshwaran1 and Mike Simpson6 1 UKCEH, Maclean Building, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BB, United Kingdom 2 UPM, Universiti Putra Malaysia Civil engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Serdang, 43400 Seri Kembangan, Selangor, Malaysia 3 UKM, Center for Research in Development, Social & Environment, FSSK Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia 4 UUM, Universiti Utara Malaysia Department of Economics and Agribusiness, School of Economics, Finance, and Banking, Sintok, 06010, Kedah, Malaysia 5 Sayers and Partners, High Street Watlington, OX49 5PY, United Kingdom 6 HR Wallingford, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BA, United Kingdom Abstract. Flooding is a recurring challenge across Malaysia, causing loss of life, extensive disruption and having a major impact on the economy. A new collaboration between Malaysia and UK, supported by the Newton-Ungku Omar Fund, aims to address a critical and neglected aspect of large-scale flood risk assessment: the representation of damage models, including exposure, vulnerability and inundation. In this paper we review flood risk and impact across Malaysia and present an approach to integrate multiple sources of information on the drivers of flood risk (hazard, exposure and vulnerability) at a range of scales (from household to national), with reference to past flood events. Recent infrastructure projects in Malaysia, such as Kuala Lumpur’s SMART Tunnel, aim to mitigate the effects of flooding both in the present and, ideally, for the foreseeable future. -

Words: Corner Beam-Column Joint; Hysteresis Loops; Seismic Design; Ductility; Stiffness; Equivalent Viscous Damping

Journal of Mechanical Engineering Vol 16(1), 213-226, 2019 Validation of Corner Beam-column Joint’s Hysteresis Loops between Experimental and Modelled using HYSTERES Program N.F. Hadi, M. Mohamad Faculty of Civil Engineering, Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia N.H. Hamid Institute of Infrastructure Engineering Sustainability and Management Universiti Teknologi MARA 40450 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia ABSTRACT The beam - column joint is an important part of a multi-storey RC building as it caters for lateral and gravitational load during an earthquake event. The beam-column joints should have a medium to high ductility for transferring the earthquake load and gravity load to the foundation. By designing multi- storey RC buildings using Eurocode 8 can avoid any diagonal shear cracks in column which is a major problem in non-seismic design buildings using British Standard (BS8110). This paper presents the experimental hysteresis loops of monolithic corner beam-column joints of multi-storey building which had been designed using Eurocode 8 and tested under in-plane lateral cyclic loading. The experimental hysteresis loops of corner beam-column joint was compared with modelled using the HYSTERES program. The full-scale corner beam- column joint of a two story precast school building was designed, constructed, tested and modelled is presented herein. The seismic performance parameters such as lateral strength capacity, stiffness, ductility and equivalent viscous damping were compared between experimental and modelled hysteresis loops. The experimental hysteresis loops have similar shape with the modeling hysteresis loops with small percentage differences between them. Keywords: Corner beam-column joint; hysteresis loops; seismic design; ductility; stiffness; equivalent viscous damping ___________________ ISSN 1823-5514, eISSN2550-164X Received for review: 2017-07-10 © 2016 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Accepted for publication: 2018-05-18 Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Malaysia. -

World Bank Document

~ Jf INTEXTATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT Public Disclosure Authorized URBA AND REGIONAL ECONOMICS DIVISION URBAN ANW-REGIONAL REPORT NO. 72-1 ) R-72-01 DEVE)PMIET ISSJES IN THE STATES OF KELANTAN, TRENGGANU Public Disclosure Authorized AND PA HANG, MALAYSIA' JOHN C. ENGLISH SEPTEMBER 1972 Public Disclosure Authorized These materials are for internal ulse on2;7 auid are circulated to stimulate discussion and critical coxmment. Views are those of the author and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the World Bank. References in publications to Reports should be cleared -iith the author to protect the Public Disclosure Authorized tentative character of these papers. DEVELOPMENT ISSUES IN THE STATES OF KELANTAN, TRENGGANU AND PAHANG, MALAYSIA Table of Contents Introduction 2. Economic and Social Conditions 2.1 Population 2.2 Employment Characteristics 2.3 Incomes 2.4 Housing 2.5 Health 2.6 Transportation 2.7 Private Services 3. Economic Activity 3.1 Agriculture 3.2 Fisheries 3.3 Forestry 3.4 Manufacturing 3.5 Trade 4. Development to 1975 4.1 Agriculture and Land Development 4.2 Forestry 4.3 Projection of Agricultural and Forestry Output 4.4 Manufacturing Page 5. Conclusions 87 5.1 Transportation Links 89 5.2 Industrial Policy 92 5.3 The Role of Kuantan 96 5 .4 The Significance of Development in Pahang Tenggara 99 5.5 Racial-Balance 103 Tables and Figures 106 ~. + A5Af2;DilXlt2¢:;uessor-c.iL?-v ylixi}Ck:. -. h.bit1!*9fwI-- 1. Introduction The following report is based on the findings of a mission to Malaysia from July 3 to 25, 1972- by Mr. -

Natural Disasters 48

ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER THREAT ECOLOGICAL ECOLOGICAL THREAT REGISTER 2020 2020 UNDERSTANDING ECOLOGICAL THREATS, RESILIENCE AND PEACE Institute for Economics & Peace Quantifying Peace and its Benefits The Institute for Economics & Peace (IEP) is an independent, non-partisan, non-profit think tank dedicated to shifting the world’s focus to peace as a positive, achievable, and tangible measure of human well-being and progress. IEP achieves its goals by developing new conceptual frameworks to define peacefulness; providing metrics for measuring peace; and uncovering the relationships between business, peace and prosperity as well as promoting a better understanding of the cultural, economic and political factors that create peace. IEP is headquartered in Sydney, with offices in New York, The Hague, Mexico City, Brussels and Harare. It works with a wide range of partners internationally and collaborates with intergovernmental organisations on measuring and communicating the economic value of peace. For more information visit www.economicsandpeace.org Please cite this report as: Institute for Economics & Peace. Ecological Threat Register 2020: Understanding Ecological Threats, Resilience and Peace, Sydney, September 2020. Available from: http://visionofhumanity.org/reports (accessed Date Month Year). SPECIAL THANKS to Mercy Corps, the Stimson Center, UN75, GCSP and the Institute for Climate and Peace for their cooperation in the launch, PR and marketing activities of the Ecological Threat Register. Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 Key Findings -

Cover 2Nd Asean Env Report 2000

SecondSecond ASEANASEAN State State ofof thethe EnvironmentEnvironment ReportReport 20002000 Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 Our Heritage Our Future Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 Published by the ASEAN Secretariat For information on publications, contact: Public Information Unit, The ASEAN Secretariat 70 A Jalan Sisingamangaraja, Jakarta 12110, Indonesia Phone: (6221) 724-3372, 726-2991 Fax : (6221) 739-8234, 724-3504 ASEAN website: http://www.aseansec.org The preparation of the Second ASEAN State of the Environment Report 2000 was supervised and co- ordinated by the ASEAN Secretariat. The following focal agencies co-ordinated national inputs from the respective ASEAN member countries: Ministry of Development, Negara Brunei Darussalam; Ministry of Environment, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia; Ministry of State for Environment, Republic of Indonesia; Science, Technology and Environment Agency, Lao People’s Democratic Republic; Ministry of Science Technology and the Environment, Malaysia; National Commission for Environmental Affairs, Union of Myanmar; Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Republic of the Philippines; Ministry of Environment, Republic of Singapore; Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, Royal Kingdom of Thailand; and Ministry of Science, Technology and the Environment, Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. The ASEAN Secretariat wishes to express its sincere appreciation to UNEP for the generous financial support provided for the preparation of this Report. The ASEAN Secretariat also wishes to express its sincere appreciation to the experts, officials, institutions and numerous individuals who contributed to the preparation of the Report. Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, and to fully acknowledge all sources of information, graphics and photographs used in the Report. -

Effect of Fine Content on Soil Dynamic Properties

Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Vol. 13, No. 4 (2018) 851 - 861 © School of Engineering, Taylor’s University EFFECT OF FINE CONTENT ON SOIL DYNAMIC PROPERTIES J. X. LIM, M. L. LEE*, Y. TANAKA Department of Civil Engineering, Lee Kong Chian Faculty of Engineering and Science, Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman, 43000, Kajang, Selangor DE, Malaysia *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Abstract Dynamic properties of soil have attracted an increasing attention among geotechnical engineers in Malaysia owing to the frequent earthquake incidents reported recently and the demand of high speed railway infrastructures. The present study investigated the effect of fine content on the soil dynamic properties based on three selected soils in Malaysia. One sand mining trail (i.e. silty sand) and two tropical residual soils (i.e. sandy clay and sandy silt) were tested on a 1 g shaking table. The experimental shear moduli were compared with the established degradation curves of sandy and clayey soils obtained from literature. The shear moduli attenuated with the increase of shear strain amplitude for the three soil samples. The amount of fine content in the soil was found to be a more dominant factor affecting the dynamic properties of soil compared with the plasticity and geological characteristics of the soil. The experimental shear moduli of sandy silt were similar to that of sandy clay. It may be attributed to the fact that the two studied residual soils have a similar amount of fine content. In addition, the shear moduli of the studied residual soils could not be fitted to the degradation curves of sand and clay which have been well studied in the past. -

Malaysia Country Report 19 Asia Construct Conference Jakarta

Malaysia Country Report 19th Asia Construct Conference Jakarta, Indonesia Prepared by Business Division, Corporate and Business Sector Construction Industry Development Board (CIDB) Malaysia Level 34, Menara Dato’ Onn, Putra World Trade Centre (PWTC), No. 45, Jalan Tun Ismail, 50480 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia [email protected] 1. Executive Summary The Malaysian economy recorded a higher, respectable growth of 5.6% in 2012. The construction sector expanded strongly at 18.1% in 2012 (2011: 4.7%), due to commencement and progress of several major infrastructure projects that also provided significant positive spill over effects to domestic manufacturing and services sector. The private sector continued its domination, obtaining projects awarded in 2012 worth RM101.3 billion or 85.2% of the total value of projects for the year. The public sector took a back seat with only RM17.6 billion or 14.8% of construction projects awarded for the same period. The main building material prices in 2012 increased marginally compared to 2011. Wages of construction personnel too were showing the same upward trend. The number of registered construction workers, as in previous years, steadily increased. Malaysian economy is expected to grow moderately in 2013 by 4.5% - 5.0%. Under the 2014 Budget, the government targeted the construction sector to grow by 10.6% in 2013 and 9.6% in 2014. CIDB estimated that the value of construction projects awarded may reach RM110.0 billion in 2013 and RM115.0 bilion in 2014. 2. Macroeconomic Review 2.1. Overview of the National Economy Overview of the Malaysian Economy in 2012 The Malaysia economy performed better with a higher growth of 5.6% (2011: 5.1%). -

DISASTER RISK MAPPING and ASSESSMENT (GEORISK 2019) 25-27 February 2019 @ KBN, KUNDASANG, SABAH

WORKSHOP & FORUM ON GEOSPATIAL TECHNOLOGY FOR DISASTER RISK MAPPING AND ASSESSMENT (GEORISK 2019) 25-27 February 2019 @ KBN, KUNDASANG, SABAH THEME: ADVANCING SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION Workshop & Forum on Geospatial DATE: Technology for Disaster Risk Mapping and 25- 27 FEBRUARY 2019 Assessment (GeoRisk2019) aims to provide an insight into modern and advanced geospatial technology fo r mapping, VENUE: analysing and assessing multi-geohazard KBN KUNDASANG,SABAH and disaster risk in a complex environment. Organized by Global and regional ca s e studies, covering Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM) Kuala Lumpur several benchmarking and best practices will be interactively discussed. This co u rs e With the support of Department of Minerals and Geoscience Malaysia (JMG) addresses the importance of Department of Surveying and Mapping Malaysia (JUPEM) understanding georisk, strengthening risk Sabah Lands and Surveys Department (JTU) governance and elevating disaster Royal Institution of Surveyors Malaysia (RISM) preparedness. New, cutting-edge mapping Society for Engineering Geology and Rock Mechanics (SEGRM) technology (UAV, Terrestrial laser scanning, LiDAR, GNSS, Remote Sensing) coupling Disaster Prevention Research Institute, Kyoto University, Japan with BigData Analytics, early-warning Japan-ASEAN Science, Technology and Innovative Platform system, monitoring system and predictive Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction WG, modelling will be shared. Ad va n ced earth Global Young Academy (GYA) observation and geospatial data are highly International Council for Science (ISC)ROAP in demand fo r disaster mitigation, prevention, risk assessment and reduction strategies in a changing climate. GeoRisk2019 promotes an intelligent, integrated and transdisciplinary approach for reducing disaster risk, as in line with the Fee: RM800/person - 3 Days 2 nights Sendai Framework fo r Disaster Risk • Inclusive airport transfer (only limited pick-up time); accommodation @ KBN Ku nd a sa n g; daily Reduction 2015-2030 and national policies. -

Mitigation & Adaptation to Floods in Malaysia

MITIGATION & ADAPTATION TO FLOODS IN MALAYSIA A study on community perceptions and responses to urban flooding in Segamat RESEARCHERS MONASH UNIVERSITY SEACO Alasdair Sach, Ashley Wild, Hoeun Im, Mohd Hanif Kamarulzaman, Nicholas Yong, Rebekah Baynard-Smith Muhammad Hazwan Miden, Mohd Fakhruddin Fiqri, Umi Salaman Md Zin 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ________________________________________________ 3 INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________ 4 RESEARCH AIMS & OBJECTIVES _______________________________________ 5 Aims _________________________________________________________________________ 5 Objectives _____________________________________________________________________ 5 BACKGROUND _______________________________________________________ 6 METHODOLOGY _____________________________________________________ 9 Participants ____________________________________________________________________ 9 Location ______________________________________________________________________ 10 Data Collection ________________________________________________________________ 11 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) _________________________________________________ 11 Interviews ____________________________________________________________________ 11 Observation Walks _____________________________________________________________ 12 Data Analysis _________________________________________________________________ 12 Ethical considerations ___________________________________________________________ 13 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS _________________________________________