Malaysia Country Report 19 Asia Construct Conference Jakarta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 8: Damages Caused by Natural Disasters

Building Disaster and Climate Resilient Cities in ASEAN Draft Finnal Report APPENDIX 8: DAMAGES CAUSED BY NATURAL DISASTERS A8.1 Flood & Typhoon Table A8.1.1 Record of Flood & Typhoon (Cambodia) Place Date Damage Cambodia Flood Aug 1999 The flash floods, triggered by torrential rains during the first week of August, caused significant damage in the provinces of Sihanoukville, Koh Kong and Kam Pot. As of 10 August, four people were killed, some 8,000 people were left homeless, and 200 meters of railroads were washed away. More than 12,000 hectares of rice paddies were flooded in Kam Pot province alone. Floods Nov 1999 Continued torrential rains during October and early November caused flash floods and affected five southern provinces: Takeo, Kandal, Kampong Speu, Phnom Penh Municipality and Pursat. The report indicates that the floods affected 21,334 families and around 9,900 ha of rice field. IFRC's situation report dated 9 November stated that 3,561 houses are damaged/destroyed. So far, there has been no report of casualties. Flood Aug 2000 The second floods has caused serious damages on provinces in the North, the East and the South, especially in Takeo Province. Three provinces along Mekong River (Stung Treng, Kratie and Kompong Cham) and Municipality of Phnom Penh have declared the state of emergency. 121,000 families have been affected, more than 170 people were killed, and some $10 million in rice crops has been destroyed. Immediate needs include food, shelter, and the repair or replacement of homes, household items, and sanitation facilities as water levels in the Delta continue to fall. -

Flood Impacts Across Scales: Towards an Integrated Multi-Scale Approach for Malaysia

Flood Impacts Across Scales: towards an integrated multi-scale approach for Malaysia Victoria Bell1,a, Balqis Rehan2, Bakti Hasan-Basri4, Helen Houghton-Carr1, James Miller1, Nick Reynard1, Paul Sayers5, ElizaBeth Stewart1, Mohd Ekhwan Toriman2, Badronnisa YusuF2, Zed Zulkafli2, Sam Carr5, Rhian Chapman1, Helen Davies1, Eva Fatdillah2, Matt Horritt5, ShaBir KaBirzad2, Alexandra Kaelin1, Tochukwu Okeke2, PonnamBalam Rameshwaran1 and Mike Simpson6 1 UKCEH, Maclean Building, Crowmarsh Gifford, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BB, United Kingdom 2 UPM, Universiti Putra Malaysia Civil engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Serdang, 43400 Seri Kembangan, Selangor, Malaysia 3 UKM, Center for Research in Development, Social & Environment, FSSK Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Selangor, Malaysia 4 UUM, Universiti Utara Malaysia Department of Economics and Agribusiness, School of Economics, Finance, and Banking, Sintok, 06010, Kedah, Malaysia 5 Sayers and Partners, High Street Watlington, OX49 5PY, United Kingdom 6 HR Wallingford, Howbery Park, Wallingford, Oxfordshire, OX10 8BA, United Kingdom Abstract. Flooding is a recurring challenge across Malaysia, causing loss of life, extensive disruption and having a major impact on the economy. A new collaboration between Malaysia and UK, supported by the Newton-Ungku Omar Fund, aims to address a critical and neglected aspect of large-scale flood risk assessment: the representation of damage models, including exposure, vulnerability and inundation. In this paper we review flood risk and impact across Malaysia and present an approach to integrate multiple sources of information on the drivers of flood risk (hazard, exposure and vulnerability) at a range of scales (from household to national), with reference to past flood events. Recent infrastructure projects in Malaysia, such as Kuala Lumpur’s SMART Tunnel, aim to mitigate the effects of flooding both in the present and, ideally, for the foreseeable future. -

ANALYST BRIEFING Quarter Ended 31 March 2019

ANALYST BRIEFING Quarter ended 31 March 2019 www.mrcb.com Table of Contents MRCB Group Overview 3 Financial Performance 8 Business Model 4 Segmental Reporting: Overview 12 MRCB Financial Summary 6 Segmental Reporting: Property Development 13 YTD 2019 Highlights 7 & Investment Segmental Reporting: Engineering, Construction 16 & Environment 1. MRCB Group Overview 2 core activities: Property Development & Investment Engineering, Construction & Environment Other activities: Facilities Management & Parking Pioneered Transport Oriented Development (“TOD”) in Malaysia Property investment is conducted through 27.94% owned MRCB-Quill REIT 3 2. Business Model – Property Development & Investment Bespoke Buildings Pre-let on Long Term Leases • Purpose built buildings • Carries more value due to customisation • Profits from lease income and possible disposal in the future Bespoke Buildings for Sale • Pre-sell to owner occupiers or other purchaser • Purpose built buildings • Profits recognised progressively based on percentage completion of construction Build Residential and Retail Commercial Developments • Mostly within MRCB TODs • Entire development is self-sustaining and integrated with easy transport access • Profits recognised progressively based on percentage completion of construction Income from Land Sales • Extract maximum value from urban land bank • Free up capital that can then be deployed elsewhere Income from Investment Properties via MQREIT • Dispose investment properties to MQREIT, in return of cash and units in the REIT • Cash is recycled -

Urban Community Forest Bukit Persekutuan

Reconnect- Immediate benefit – Connection as a youth Urban Community Forest Bukit Persekutuan Project Partners “All of the trees and vegetation within a town, village, or city make up the ‘community forest’. The ommunity forest can include street and yard trees, parks, cemeteries, school grounds, and undeveloped green spaces. The urban community forest also contains wildlife, waterways, built roads and structures, and people. This is where most people in Kuala Lumpur live and work.” Adapted from the website of New York State Dept. of Environmental Conservation 1 Compiled by: Sonny Wong, Annabelle Aiyling Mew and Balu Perumal © Malaysian Nature Society (MNS). 2017 Malaysian Nature Society JKR 641 Jalan Kelantan Bukit Persekutuan 50480 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia T: 03 22879422 F: 03-2287 8773 [email protected] www.mns.my www.bukitpersekutuan.wordpress.com fB: MNS Urban Community Forest Cover photo: Western Digital volunteers at the UCF nursery, Bukit Persekutuan All photographs belongs to MNS. This report is produced by the MNS. Any reproduction, in full or part, of this publication must mention the title, authors and credit MNS as the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Wong, C.H. , Mew, A.A. & Perumal, B., 2017. Urban Community Forest, Bukit Persekutuan. Malaysian Nature Society. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................... 4 Conserving UCF Bukit Persekutuan timeline .................................................................................................... -

Mitigation & Adaptation to Floods in Malaysia

MITIGATION & ADAPTATION TO FLOODS IN MALAYSIA A study on community perceptions and responses to urban flooding in Segamat RESEARCHERS MONASH UNIVERSITY SEACO Alasdair Sach, Ashley Wild, Hoeun Im, Mohd Hanif Kamarulzaman, Nicholas Yong, Rebekah Baynard-Smith Muhammad Hazwan Miden, Mohd Fakhruddin Fiqri, Umi Salaman Md Zin 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ________________________________________________ 3 INTRODUCTION ______________________________________________________ 4 RESEARCH AIMS & OBJECTIVES _______________________________________ 5 Aims _________________________________________________________________________ 5 Objectives _____________________________________________________________________ 5 BACKGROUND _______________________________________________________ 6 METHODOLOGY _____________________________________________________ 9 Participants ____________________________________________________________________ 9 Location ______________________________________________________________________ 10 Data Collection ________________________________________________________________ 11 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) _________________________________________________ 11 Interviews ____________________________________________________________________ 11 Observation Walks _____________________________________________________________ 12 Data Analysis _________________________________________________________________ 12 Ethical considerations ___________________________________________________________ 13 FINDINGS AND DISCUSSIONS _________________________________________ -

The Case of Floods’, in Sawada, Y

Chapter 14 Impacts of Disasters and Disasters Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods Ngai Weng Chan Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang, Malaysia December 2012 This chapter should be cited as Chan, N. W. (2012), ‘Impacts of Disasters and Disasters Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods’, in Sawada, Y. and S. Oum (eds.), Economic and Welfare Impacts of Disasters in East Asia and Policy Responses. ERIA Research Project Report 2011-8, Jakarta: ERIA. pp.503-551. CHAPTER 14 Impacts of Disasters and Disaster Risk Management in Malaysia: The Case of Floods NGAI WENG CHAN* Universiti Sains Malaysia Malaysia lies in a geographically stable region, relatively free from natural disasters, but is affected by flooding, landslides, haze and other man-made disasters. Annually, flood disasters account for significant losses, both tangible and intangible. Disaster management in Malaysia is traditionally almost entirely based on a government-centric top-down approach. The National Security Council (NSC), under the Prime Minister’s Office, is responsible for policies and the National Disaster Management and Relief Committee (NDMRC) is responsible for coordinating all relief operations before, during and after a disaster. The NDMRC has equivalent organizations at the state, district and “mukim” (sub-district) levels. In terms of floods, the NDMRC would take the form of the National Flood Disaster Relief and Preparedness Committee (NFDRPC). Its main task is to ensure that assistance and aid are provided to flood victims in an orderly and effective manner from the national level downwards. Its approach is largely reactive to flood disasters. The NFDRPC is activated via a National Flood Disaster Management Mechanism (NFDMM). -

PDF Senarai Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara

Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 MAKLUMAT ALAMAT, NO TELEFON DAN FAKS PAGN Bil ALAMAT NO TEL EMAIL JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Batu Pahat No. 7, Jalan Gunung Soga 1 - [email protected] 83000, Batu Pahat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Felda Tenggaroh 2 No.1, Jalan Cempaka 2 07-7911059 [email protected] Felda Tenggaroh 2 86810 Mersing JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Parit Guntong TLJM 336 Parit Guntong 3 07-4163036 [email protected] Mukim Lubok, Semerah 83600, Batu Pahat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Segamat LOT 15550 Mukim Sg Segamat 4 Bandar Putra 07-9432385 [email protected] 85000 Segamat JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Kulaijaya LOT 23780, Jalan Sri Putri 1/13 07-6623117 5 [email protected] Taman Putri, 81000 Kulaijaya 07-6623257 JOHOR Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Pasir Gudang PTD 158017 Persimpangan Jalan 6 Gunung 07-3861070 [email protected] Jalan Gunung 41, Bandar Sri Alam 81750 Masai JOHOR Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Pengerang Lot PTD 7329, Taman Bayu Damai 7 Mukim Pantai Timur, Daerah Kecil 07-8263075 [email protected] Pengerang 81620, Kota Tinggi, Johor Kemaskini 22 Julai 2019 Bil ALAMAT NO TEL EMAIL MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Bukit Peringgit 8 No. 47 Kuarters Kerajaan 06-2821309 [email protected] 75150 Bukit Peringgit MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Jasin Lot PT 5566, Jalan Melaka, Taman 9 Bahagia 06-5292791 [email protected] 77000, Jasin MELAKA Pusat Anak GENIUS Negara Bukit Katil Lot PT 5497, Kawasan MITC, Ayer 10 06-2325173 [email protected] -

(Covid-19) Di Malaysia 10 November 2020

KENYATAAN AKHBAR KEMENTERIAN KESIHATAN MALAYSIA SITUASI SEMASA JANGKITAN PENYAKIT CORONAVIRUS 2019 (COVID-19) DI MALAYSIA 10 NOVEMBER 2020 STATUS TERKINI KES DISAHKAN COVID-19 YANG TELAH PULIH Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia (KKM) ingin memaklumkan bahawa pada hari ini, Malaysia mencatatkan bilangan kes pulih COVID-19 sebanyak 725 kes. Ini menjadikan jumlah kumulatif kes yang telah pulih sepenuhnya dari COVID-19 adalah 30,304 kes (72.1 peratus daripada jumlah keseluruhan kes). Pecahan kes yang sembuh adalah seperti berikut: • Sabah (356 kes); • Selangor (160 kes); • Negeri Sembilan (46 kes); • Wilayah Persekutuan Labuan (45 kes); • Pulau Pinang (29 kes); 1 • Kedah (21 kes); • Johor (19 kes); • Sarawak (19 kes); • Terengganu (13 kes); • Perak (7 kes); • WP Kuala Lumpur & Putrajaya (4 kes); • Pahang (3 kes); dan • Kelantan (3 kes). STATUS TERKINI KES COVID-19 DI MALAYSIA Secara keseluruhannya, sehingga 10 November 2020 pukul 12:00 tengah hari, sebanyak 869 kes baharu telah dilaporkan menjadikan jumlah kes positif COVID-19 di Malaysia adalah sebanyak 42,050 kes. Manakala, jumlah kes aktif dengan kebolehjangkitan COVID-19 pula adalah 11,446 kes. Untuk makluman, negeri Sabah mencatatkan sebanyak 397 kes (45.7 peratus) daripada keseluruhan kes positif pada hari ini. Negeri-negeri di Lembah Klang pula mencatatkan sebanyak 258 kes (29.7 peratus) daripada jumlah keseluruhan. Sebanyak 28 kes (3.2 peratus) yang dilaporkan adalah berkaitan kluster-kluster di Pusat Tahanan Sementara (PTS) dan penjara. 2 Ini melibatkan Kluster Penjara Seberang Perai (13 kes), Penjara Kepayan (6 kes), Kluster PTS Tawau (3 kes), Kluster Penjara Sandakan (2 kes), Kluster Rumah Merah (2 kes) dan Kluster GK Tawau (2 kes). -

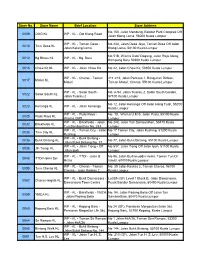

No Store Name Area Zone Outlet Address Ez Smart

EZ SMART PARK MERCHANT LIST NO STORE NAME AREA ZONE OUTLET ADDRESS NO. 205, JALAN GENTING KELANG, TAMAN AYER PANAS, 53300 KUALA LUMPUR. 1 KK SUPER MART AYER PANAS ZONE C 2 NO.522, JALAN AIR JERNEH, OFF JALAN AIR PANAS, SETAPAK, 53200 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.43-0-7, JALAN 1/48A, SENTUL PERDANA, BANDAR 2 KK SUPER MART BANDAR BARU SENTUL ZONE B 1 BARU SENTUL, 51000 KUALA LUMPUR. NO. 31, JALAN WANGSA DELIMA 13, WANGSA LINK@ 3 KK SUPER MART BANDAR BARU WANGSA MAJU ZONE C 1 SHOP OFFICE, PUSAT BANDAR WANGSA MAJU, 53300 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.25, JALAN SRI PERMAISURI 8, BANDAR SRI 4 KK SUPER MART BANDAR SRI PERMAISURI ZONE C 1 PERMAISURI, 56000 KUALA LUMPUR. NO. 6, JALAN 30A/146, DESA TASIK, SUNGAI BESI, 5 KK SUPER MART BANDAR TASIK SELATAN ZONE C 1 57000 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.68, JALAN JUJUR, BANDAR TUN RAZAK, 56000 6 KK SUPER MART BANDAR TUN RAZAK ZONE C 1 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.8, JALAN TELAWI, BANGSAR BARU, 59100 KUALA LUMPUR. NO. 88, LORONG MAAROF, BANGSAR PARK, 59000 7 KK SUPER MART BANGSAR ZONE B 3 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.36, JALAN TELAWI 2, BANGSAR BARU, 59100 KUALA LUMPUR. NO. 26, JALAN BANGSAR UTAMA 1, BANGSAR UTAMA, 8 KK SUPER MART BANGSAR UTAMA ZONE B 1 59000 KUALA LUMPUR. NO.112, JALAN TUN SAMBANTHAN, 50470 KUALA LUMPUR. KK SUPER MART NO: 13, JALAN TUN SAMBANTHAN 4, BRICKFIELDS, 50470 KUALA LUMPUR. 280, JALAN TUN SAMBANTHAN, BRICKFIELDS, 50470 STS CONNECTION KUALA LUMPUR NO 42, JALAN TUN SAMBATHAN 3, BRICKFIELDS, 9 HORIZON ENTERPRISE BRICKFIELDS ZONE B 7 50470 KUALA LUMPUR NO 2, JALAN THAMBIPILLAY, BRICKFIELDS, 50470 TECK SOON LOCKSMITH KUALA LUMPUR NO 39, JALAN THAMBIPILLAY, BRICKFIELDS 50470 CHEEMA MANAGEMENT SDN BHD KUALA LUMPUR 116, JALAN SULTAN ABDUL SAMAD, BRICKFIELDS, SILVER EXPRESS ENTERPRISE 50470 KUALA LUMPUR EZ SMART PARK MERCHANT LIST NO STORE NAME AREA ZONE OUTLET ADDRESS NO.75, JALAN BUKIT BINTANG, 55100 KUALA LUMPUR. -

Fostering Economic Growth A

Kuala Lumpur | Johor Bahru | George Town | Kuantan | Kota Kinabalu | Kuching | Kota | Kuantan | Johor Bahru George Town Lumpur Kuala Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized of Competitive Cities inMalaysia of Competitive Achieving aSystem Achieving Main Report Achieving a System of Competitive Cities in Malaysia Main Report World Bank Reimbursable Advisory Service Social, Urban, Rural, and Resilience Global Practice November 2015 For further information refer to: Director General, Economic Planning Unit Prime Minister’s Department Block B5 & B6 Federal Government Administrative Centre 62502 PUTRAJAYA Website: www.epu.gov.my All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means - electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise; without prior permission of Economic Planning Unit, Prime Minister’s Department, Malaysia. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................................ xi Glossary ....................................................................................................................................................... xii Key Facts ..................................................................................................................................................... xiii Overview .....................................................................................................................................................xiv -

Store No. Store Name Brief Location Store Address 0009 OUG KL WP

Store No. Store Name Brief Location Store Address No 150, Jalan Mendung, Bandar Park Complek Off 0009 OUG KL WP - KL - Old Klang Road Jalan Klang Lama, 58000 Kuala Lumpur WP - KL - Taman Desa - No 23A, Jalan Desa Jaya, Taman Desa Off Jalan 0010 Tmn Desa KL Jalan Kelang Lama Klang Lama, 58100 Kuala Lumpur No 51B, Wisma Dato' Dagang, Jalan Raja Alang, 0012 Kg Bharu KL WP - KL - Kg. Baru Kampung Baru 50300 Kuala Lumpur 0016 Chow Kit KL WP - KL - Jalan Chow Kit No 42, Jalan Chow Kit, 50350 Kuala Lumpur WP - KL - Cheras - Taman 211-213, Jalan Perkasa 1, Bangunan Dirikon, 0017 Maluri KL Maluri Taman Maluri, Cheras, 55100 Kuala Lumpur WP - KL - Salak South - No. A-94, Jalan Tuanku 2, Salak South Garden, 0022 Salak South KL Jalan Tuanku 2 57100 Kuala Lumpur No 12, Jalan Kenanga Off Jalan Hang Tuah, 55200 0023 Kenanga KL WP - KL - Jalan Kenanga Kuala Lumpur WP - KL - Pudu Raya - No. 10, Wisma U.M.S, Jalan Pudu, 55100 Kuala 0025 Pudu Raya KL Wisma UMS Lumpur WP - KL - Brickfields - Jalan No 243, Jalan Tun Sambanthan, 50470 Kuala 0032 Brickfields KL Tun Sambanthan No. 243 Lumpur WP - KL - Taman City - Jalan No 17 Taman City, Jalan Kuching, 51200 Kuala 0035 Tmn City KL Kuching Lumpur WP - KL - Bukit Bintang - 0036 Bukit Bintang KL No 77, Jalan Bukit Bintang, 55100 Kuala Lumpur Jalan Bukit Bintang No. 77 WP - KL - Jalan Tiong - Off No 537, Jalan Tiong Off Jalan Ipoh, 51100 Kuala 0038 Jln Tiong KL Jalan Ipoh Lumpur WP - KL - TTDI - Jalan B. -

2Nd Half 2013 Real Estate Highlights Kuala Lumpur | Penang | Johor Bahru

Research 2nd Half 2013 real estate highlights Kuala Lumpur | Penang | Johor Bahru Highlights Kuala Lumpur: The residential market is expected to self-correct in the next six to twelve months with the impending implementation of more cooling measures and is expected to see lower volume of transactions going forward. With the expansion of the Oil & Gas sector and concerted efforts by InvestKL to attract MNCs to the country, we expect more activity in the office leasing market. The Klang Valley retail market continues to draw interests of international retailers and drive the expansion of existing brands despite the slowdown in retail sales growth. The various Government initiatives proposed under the recent Budget 2014 announcement to encourage investments to build new 4 and 5-star hotels to promote Malaysia as the destination of choice, augur well for the Kuala Lumpur hotel market. Penang: Komtar Tower will undergo a RM50 million revitalization and rejuvenation exercise that includes refurbishment to levels 5, 59, 60, 64 & 65 to create high-end commercial space for retail, food and beverage and recreational purposes. With no immediate incoming supply of office space into Penang Island, occupancy rates in the short term are expected to improve. Johor: JB property market is expected to remain firm in the medium term with more Malaysian and Singaporean- based developers expected to venture into the Iskandar region. Medini will continue to be the ‘hotspot’ given its special economic zone status. 2nd Half 2013 REAL ESTATE HIGHLIGHTS Kuala Lumpur | Penang | Johor Bahru Kuala Lumpur High End Condominium Market located bordering the Golden Triangle and Market Indications Central Business District of Kuala Lumpur, has achieved 95% sales rate since its launch in Malaysia’s economy grew by 5% in 3Q2013, 2011, with only the larger size units still higher than the 4.4% growth recorded in available for sale.