Chapter 5 Iran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iran's Persian Gulf Policy

IRAN’S PERSIAN GULF POLICY This book discusses the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic of Iran towards the states of the Persian Gulf from 1979 to 1998. It covers the perceptions Iranians and Arabs have of each other, Islamic revolutionary ideology, the Iran–Iraq war, the Gulf Crisis, the election of President Khatami and finally the role of external powers, such as the United States, in the region. Iran’s foreign policy has been more ideology based in the past but has become increasingly pragmatic. Today, Iran’s Persian Gulf policy does not differ greatly from that under the Shah. By tracing the policy over the past two decades, including a large number of interviews, the book helps to anticipate the relationship between Iran and the Gulf states. Christin Marschall completed her MPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies at St Antony’s College, Oxford, and received her PhD in History and Middle Eastern Studies from Harvard University. She lives in London and travels frequently to Iran and the Arab world. The mightiest of the princes of the world Came to the least considered of his courtiers; Sat down upon the fountain’s marble edge, One hand amid the goldfish in the pool; And thereupon a colloquy took place That I commend to all the chroniclers To show how violent great hearts can lose Their bitterness and find the honeycomb. ‘The Gift of Harun al-Rashid’, W.B. Yeats IRAN’S PERSIAN GULF POLICY From Khomeini to Khatami Christin Marschall TO TIM First published 2003 by RoutledgeCurzon 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by RoutledgeCurzon 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1999, No.36

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Forced/slave labor compensation negotiations — page 2. •A look at student life in the capital of Ukraine — page 4. • Canada’s professionals/businesspersons convene — pages 10-13. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXVII HE No.KRAINIAN 36 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 1999 EEKLY$1.25/$2 in Ukraine U.S.T continues aidU to Kharkiv region W Pustovoitenko meets in Moscow with $16.5 million medical shipment by Roman Woronowycz the region and improve the life of Kharkiv’s withby RomanRussia’s Woronowycz new increasingprime Ukrainian minister debt for Russian oil Kyiv Press Bureau residents, which until now had produced Kyiv Press Bureau and gas. The disagreements have cen- few tangible results. tered on the method of payment and the KYIV – The United States government “This is the first real investment in terms KYIV – Ukraine’s Prime Minister amount. continued to expand its involvement in the of money,” said Olha Myrtsal, an informa- Valerii Pustovoitenko flew to Moscow on Ukraine has stated that it owes $1 bil- Kharkiv region of Ukraine on August 25 tion officer at the U.S. Embassy in Kyiv. August 27 to meet with the latest Russian lion, while Russia claims that the costs when it delivered $16.5 million in medical Sponsored by the Department of State, the prime minister, Vladimir Putin, and to should include money owed by private equipment and medicines to the area’s hos- humanitarian assistance program called discuss current relations and, more Ukrainian enterprises, which raises the pitals and clinics. -

Ukraine Nuclear Fuel Cycle Chronology

Ukraine Nuclear Fuel Cycle Chronology Last update: April 2005 This annotated chronology is based on the data sources that follow each entry. Public sources often provide conflicting information on classified military programs. In some cases we are unable to resolve these discrepancies, in others we have deliberately refrained from doing so to highlight the potential influence of false or misleading information as it appeared over time. In many cases, we are unable to independently verify claims. Hence in reviewing this chronology, readers should take into account the credibility of the sources employed here. Inclusion in this chronology does not necessarily indicate that a particular development is of direct or indirect proliferation significance. Some entries provide international or domestic context for technological development and national policymaking. Moreover, some entries may refer to developments with positive consequences for nonproliferation. 2003-1993 1 August 2003 KRASNOYARSK ADMINISTRATION WILL NOT ALLOW IMPORT OF UKRAINE'S SPENT FUEL UNTIL DEBT PAID On 1 August 2003, UNIAN reported that, according to Yuriy Lebedev, head of Russia's International Fuel and Energy Company, which is managing the import of spent nuclear fuel to Krasnoyarsk Kray for storage, the Krasnoyarsk administration will not allow new shipments of spent fuel from Ukraine for storage until Ukraine pays its $11.76 million debt for 2002 deliveries. —"Krasnoyarskiy kray otkazhetsya prinimat otrabotannoye yadernoye toplivo iz Ukrainy v sluchaye nepogasheniya 11.76 mln. dollarov dolga," UNIAN, 1 August 2003; in Integrum Techno, www.integrum.com. 28 February 2002 RUSSIAN REACTOR FUEL DELIVERIES TO COST $246 MILLION IN 2002 Yadernyye materialy reported on 28 February 2002 that Russian Minister of Atomic Energy Aleksandr Rumyantsev and Ukrainian Minister of Fuel and Energy Vitaliy Gayduk signed an agreement under which Ukraine will buy reactor fuel worth $246 million from Russia in 2002. -

Full Issue File

Biannual of Research Institute for Strategic Strategic for Institute Iranian Review of Foreign Affairs 31 Vol. 11. No.1. Winter&Spring2020 Advisory Board Mohsen Rezaee Mirghaed, Kamal Kharazi, Ali Akbar Velayati, Ahmad Vahidi, Saeed Jalili, Publisher Ali Shamkhanim, Hosein Amirabdolahian, Ali Bagheri Institute for Strategic Research Editorial Board Expediency Council Seyed Mohammad Kazem Sajjadpour Director Professor, School of International Relations Mohsen Rezaee Mirghaed Gulshan Dietl Associate Professor, Professor, Jawaharlal Nehru University Imam Hossein University Mohammad Marandi Professor, University of Tehran Jamshid Momtaz Editor-in-Chief Professor, University of Tehran Seyed Mohammad Kazem Mohammad Javad Zarif Sajjadpour Associate Professor, School of World Studies Professor of School of Mohiaddin Mesbahi International Relations Professor, Florida International University Hosein Salimi Professor, Allameh Tabatabii University Secretary of advisory board Seyed Jalal Dehghani Mohammad Nazari Professor, Allameh Tabatabii University Naser Hadian Director of Executive Affairs Assistant professor, University of Tehran Hadi Gholamnia Vitaly Naumkin Professor, Moscow State University Copyediting Hassan Hoseini Zeinab Ghasemi Tari Assistant Professor, University of Tehran Mohammad Ali Shirkhani Layout and Graphics Najmeh Ghaderi Professor, University of Tehran Foad Izadi Assistant Professor, University of Tehran Iranian Review of Foreign Affairs (IRFA) achieved the highest scientific ISSN: 2008-8221 grade from the Ministry of Science, -

Understanding the Role of State Identity in Foreign Policy Decision-Making

The London School of Economics and Political Science UNDERSTANDING THE ROLE OF STATE IDENTITY IN FOREIGN POLICY DECISION-MAKING The Rise and Demise of Saudi–Iranian Rapprochement (1997–2009) ADEL ALTORAIFI A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics and Political Science for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, October 2012 1 To Mom and Dad—for everything. 2 DECLARATION I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. The final word count of this thesis, including titles, footnotes and in-text citations, is 105,889 words. 3 ABSTRACT The objective of the thesis is to study the concept of state identity and its role in foreign policy decision-making through a constructivist analysis, with particular focus on the Saudi–Iranian rapprochement of 1997. While there has been a recent growth in the study of ideational factors and their effects on foreign policy in the Gulf, state identity remains understudied within mainstream International Relations (IR), Foreign Policy Analysis (FPA), and even Middle Eastern studies literature, despite its importance and manifestation in the region’s foreign policy discourses. The aim is to challenge purely realist and power-based explanations that have dominated the discourse on Middle Eastern foreign policy—and in particular, the examination of Saudi–Iranian relations. -

Iran Case File (April 2019)

IRAN CASE FILE July 2020 RASANAH International Institute for Iranian Studies, Al-Takhassusi St. Sahafah, Riyadh Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. P.O. Box: 12275 | Zip code: 11473 Contact us [email protected] +966112166696 The Executive Summary .............................................................4 Internal Affairs .........................................................................7 The Ideological File ......................................................................... 8 I. Supporters of Velayat-e Faqih and the Call to End the US Presence in Iraq .......................................................................... 8 II. Coronavirus Amid Muharram Gatherings in Najaf ............................ 9 The Political File ............................................................................12 I. The Bill to Hold Rouhani Accountable and the Conservatives’ Call for Him to Be Deposed .......................................12 II. The Supreme Leader Saves Rouhani From Interrogation and Rejects His Ouster .....................................................13 The Economic File ..........................................................................16 I. History of Economic Relations Between Iran and China .....................16 II. The Nature and Provisions of the 25-year Partnership Agreement ..... 17 III. Prospects of the Long Term Iranian-Chinese Partnership .................18 The Military File............................................................................ 20 Arab Affairs ............................................................................25 -

4Th International

4th International September 9-10, 2014 Sponsored by U.S. Department of Energy | Office of Fossil Energy | National Energy Technology Laboratory 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Synopsis .................................................................................................................3 Technology Summary .............................................................................................3 Organizing Committee ............................................................................................3 Agenda-At-A-Glance ...............................................................................................4 Sheraton Station Square Floor Plan .........................................................................5 Detailed Program for Monday, September 8, 2014 ..................................................6 Detailed Program for Tuesday, September 9, 2014 ..................................................6 Detailed Program for Wednesday, September 10, 2014 ...........................................9 Speaker/Presenter Biographies .............................................................................13 2 SYNOPSIS The 4th International Supercritical CO2 Power Cycles Symposium is a technical meeting organized and designed by industry, academia, and government agencies to advance the development of power cycles with supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2) as the working fluid. Every two to three years, researchers, industry, and end users meet to learn about advancements in the field, discuss priorities, and establish -

Iran's New Narrative: the Regime Is Not in A

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 3434 Iran’s New Narrative: The Regime Is Not in a Hurry, But Washington Should Be by Omer Carmi Feb 11, 2021 Also available in Arabic / Farsi ABOUT THE AUTHORS Omer Carmi Omer Carmi was a 2017 military fellow at The Washington Institute. Brief Analysis By steadily implementing parliament’s anti-JCPOA law and making public statements about “cornered cats” and “closing windows,” Tehran has sought to give Washington a sense of urgency, but this approach could be a double- edged sword. n January 8, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei explained that Iran is not “in a hurry” for Washington to return O to the nuclear deal, and that if sanctions are not lifted beforehand, then a U.S. return to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action “may even be detrimental” to the Islamic Republic. He further hardened this stance in a February 7 speech, refuting proposals for any sequencing mechanism in which both countries make incremental moves back to the JCPOA. Instead, he emphasized that after Washington agrees to remove sanctions, Iran “will check if [they] have truly been lifted,” and only then resume its nuclear commitments. President Hassan Rouhani fell in with this narrative three days later, declaring that he supports “negotiations with enemies” in the framework of the Islamic Republic’s national interests, and noting that Tehran will fulfill its commitments once the United States and other parties implement theirs. These remarks are just part of a broader regime campaign to show Washington that Iran will not arrive at the negotiating table from a position of weakness, but rather with clear unity of purpose. -

STRANGER THAN (SCIENCE) FICTION the Unpredicted Shrinking 2021 April of Ursula Von Der Leyen E

EUR PE Diplomatic IRANIAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Looming uncertainties… concerns…dangers COCAINE AND CASTANETS Spain’s rôle in the international drugs trade STRANGER THAN (SCIENCE) FICTION The unpredicted shrinking 2021 April of Ursula von der Leyen E 3 BRUSSELS - PARIS - GENEVA - MONACO EUROPEDIPLOMATIC IN THIS ISSUE n JABS, JOBS, AND JACKASSES The few successes and many failures of the EU Covid vaccination programme .........................................................................................................................................................................................................................p.5 n STRANGER THAN (SCIENCE) FICTION 5 The unpredicted shrinking of Ursula von der Leyen .......................................................................p.12 n IRANIAN PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION Looming uncertainties…concerns…dangers ......................................................................................................... p.18 n COCAINE AND CASTANETS 12 Spain’s rôle in the international drugs trade .................................................................................................p.28 n 20,000 TONNES UNDER THE SEA The growing use of narco-submarines in Europe .............................................................................. p.35 n NEWS IN BRIEF ....................................................................................................................................................................................................p.40 35 n POISONED ENTRAILS -

Npr 2.3: an Assessment of Iran's Nuclear Facilities

Report Report: AN ASSESSMENT OF IRAN’S NUCLEAR FACILITIES by Greg J. Gerardi and Maryam Aharinejad Greg J. Gerardi is a Senior Research Associate of the Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) at the Monterey Institute of International Studies. Maryam Aharinejad was a Research Associate at CNS; she is currently an intern at the United Nations’ Centre for Disarmament Affairs. uch press has been given to the perceived threat was no contract for a centrifuge, Yeltsin later conceded posed by Iran’s nuclear developments. In par- this point of the deal stating that: Mticular, Russia’s agreement to complete Unit ...the contract indeed has elements of both One of the nuclear complex at Bushehr, begun by the peaceful and military power engineering. Now Germans in the late 1970s, and reports of China’s assis- we have agreed to separate them, and what tance in the building of additional power reactors have bears on the military part, the possibility of strained relations between the United States and these creating, say, nuclear-weapons-grade fuel or two countries. The protocol for the completion of the other matters—the centrifuge, the building of Bushehr plant, signed by Russian nuclear energy minis- mines—we decided to exclude these matters ter Viktor Mikhailov and the President of the Atomic from the contract....2 Energy Organization of Iran (AEOI) Reza Amrollahi on U.S. concern about the transfer of any nuclear January 8, 1995, also calls on the two signatory organi- technology to Iran is based on the belief that zations to draft and sign: Iran has a clandestine nuclear weapon develop- ...within a six month period of time, a con- ment program. -

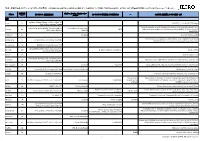

(C) 2010 JETRO. All Rights Reserved. 水力

別添 発電所案件のEPC, コントラクター等の動向 (注)情報収集が可能であった発電所のみ記載。また、各発電所について記載してある内容は全体の一部であり、全ての関連企業を掲載したものではありません。何卒ご了承下さい。 設備容量 ボイラー、タービン、ジェネレーター プラント ファイナンス (融資銀行含む) コンサルタント(詳細設計、F/S業務含む) EPC 土木工事、機器据付、システム設計 など (MW) メーカー 水力 Agribank, Vietnam-Thailand JV Bank, An Binh JSCl A Luoi 170 CAVICO, CTTE, LILAMA PECC3(Design) Bank, Rubber Financing Company Licogi, Construction corp No.4, Lung Lo Construction corp, Central Construction corp, Vietcombank, Agribank, BIDV, Incombank,Citicorp, Power Machine Group(Russia), A Vuong 210 PECC2 National research institute of mechanical engineering, LILAMA, AF-Colenco(Design), BNP Paribas, ABN Amro Mitsubishi Sika(PVC Bar) An Khe #2 80 Dongfang Song Da, Dat Phuong JSC PECC4(Construction supervision), CONSTREXIM, HUBEI HONGCHENG GENERAL An Khe Kanak 177 BIDV,Agribank, Vietcombank, Incombank MACHINERY CO., LTD., Sichuan Dongfang electric equipment corp. Ba Thuoc 1,2 120 BIDV(60%), Hoang Anh Gia Lai(40%) Agribank(56%), BIDV, Vietcombank, Global Petro Ban Chat 220 Electric Construction Consultancy 1 Licogi, CAVICO Commercial Joint Stock Bank. Ban Ve 300 Song Da, Cavico, Licogi Vietcombank, Agribank, BIDV, Incombank,Citicorp, Buon Kuop 280 Vinaconex, Cavico, CONSTREXIM, Construction Corporation No.1, Sika(PVC Bar) BNP Paribas, ABN Amro Buon Tua Srah 86 Dongfang PECC4(F/S) Lilama, CONSTREXIM, PECC4(Design, Appraisal bid documents), Sika(PVC Bar) Can Don 77.5 Incombank, BIDV, International JSC Bank Power Machine Group, UETM(Russia) Ukrhydroproject, Song Da, Lilama Cua Dat 99 VINACONEX, BNP Paribas Vinaconex, China National -

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018

Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018 Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications Peter Lobner July 2018 1 Foreword In 2015, I compiled the first edition of this resource document to support a presentation I made in August 2015 to The Lyncean Group of San Diego (www.lynceans.org) commemorating the 60th anniversary of the world’s first “underway on nuclear power” by USS Nautilus on 17 January 1955. That presentation to the Lyncean Group, “60 years of Marine Nuclear Power: 1955 – 2015,” was my attempt to tell a complex story, starting from the early origins of the US Navy’s interest in marine nuclear propulsion in 1939, resetting the clock on 17 January 1955 with USS Nautilus’ historic first voyage, and then tracing the development and exploitation of marine nuclear power over the next 60 years in a remarkable variety of military and civilian vessels created by eight nations. In July 2018, I finished a complete update of the resource document and changed the title to, “Marine Nuclear Power: 1939 – 2018.” What you have here is Part 3B: Russia - Surface Ships & Non-propulsion Marine Nuclear Applications. The other parts are: Part 1: Introduction Part 2A: United States - Submarines Part 2B: United States - Surface Ships Part 3A: Russia - Submarines Part 4: Europe & Canada Part 5: China, India, Japan and Other Nations Part 6: Arctic Operations 2 Foreword This resource document was compiled from unclassified, open sources in the public domain. I acknowledge the great amount of work done by others who have published material in print or posted information on the internet pertaining to international marine nuclear propulsion programs, naval and civilian nuclear powered vessels, naval weapons systems, and other marine nuclear applications.