Spices Form the Basis of Food Pairing in Indian Cuisine Anupam Jaina,†, Rakhi N Kb,† and Ganesh Baglerb,*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

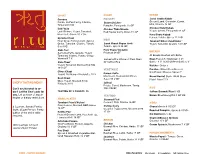

CHEF's TASTING MENU* Can't Decide What to Or- Der? Let the Chef

CHAAT CURRY KEBAB Samosa POULTRY Lamb Seekh Kebab* Ground Lamb, Coriander, Cumin, Potato, Stuffed Pastry, Cilantro, Butter Chicken* Mint, Cilantro 13 GF Tamarind 9 VG Pumpkin, Fenugreek, 15 GF Chicken Malai Kebab Dahi Vada Chicken Tikka Masala Yogurt, Cream, Fenugreek 12 GF Lentil Fritters, Yogurt, Tamarind, Red Pepper Curry, Onion 15 GF Black Salt, Cumin 10 V GF Hara Bhara Kebab Sprouts Chaat Paneer, Potato, Spices 12 V GF MEAT Flour Crisp, Pomegranate, Sprout, Tandoori Whole Cauliflower * Onion, Tamarind, Cilantro, Tomato, Lamb Shank Rogan Josh* Yogurt, Tamarind, Cilantro 14 V GF Sev 9VG Tomato, Spices 24 GF Dahi Puri* Pork Shank Vindaloo BREADS Semolina Puffs, Sprouts, Yogurt, Potatoes 24 GF All Breads Brushed with Butter Tamarind, Cilantro, Potato, Crispy Vermicelli 7 V Served with a Choice of Plain Naan Naan Plain 3.5 I Multigrain 4 V | Kale Chaat* Or Saffron Rice Garlic - 4 V I Chili Cheese Garlic 5 V Yogurt, Tamarind, Mumbai Trail Mix Kulcha - Onion 5 10 V GF VEGETABLE Paratha - Wheat Flour,Broccoli, Citrus Chaat Cauliflower, Cheese, Spices 7 Yogurt, Dry Mango Vinaigrette, 10 V Paneer Kofta Mushroom, Cashew Nut Onion Bread Basket Garlic I Multi Grain Beet Chaat Sauce16 V GF Plain I Naan 11 V Okra, Yogurt, Mustard Seed, CHEF’S TASTING MENU* Pistachio 10 V Jalfrezi Potato, Carrot, Mushroom, Turnip, Can’t decide what to or- Chili VG GF RICE der? Let the Chef cook for TASTING OF 3 CHAATS 15 Saffron Basmati Rice 5 VG you. Let us know of any al- SEAFOOD Brown Rice Moong Dal 5 GF VG lergies or dietary restrictions. -

Spice (Synthetic Marijuana)

Spice (Synthetic Marijuana) “Spice” refers to a wide variety of herbal found in Spice as Schedule I controlled mixtures that produce experiences simi- substances, making it illegal to sell, buy, lar to marijuana (cannabis) and that are or possess them. Manufacturers of Spice marketed as “safe,” legal alternatives to products attempt to evade these legal re- that drug. Sold under many names, in- strictions by substituting different chem- cluding K2, fake weed, Yucatan Fire, icals in their mixtures, while the DEA Skunk, Moon Rocks, and others—and la- continues to monitor the situation beled “not for human consumption”— and evaluate the need for updating the these products contain dried, shredded list of banned cannabinoids. plant material and chemical additives that are responsible for their psychoac- Spice products are popular among young tive (mind-altering) effects. people; of the illicit drugs most used by high-school seniors, they are second only to marijuana. (They are more popular False Advertising among boys than girls—in 2012, nearly twice as many male 12th graders report- Labels on SPice Products often claim ed past-year use of synthetic marijuana that they contain “natural” Psycho- as females in the same age group.) Easy active material taken from a variety access and the misperception that Spice of Plants. SPice Products do contain products are “natural” and therefore harmless have likely contributed to their dried plant material, but chemical popularity. Another selling point is that analyses show that their active in- the chemicals used in Spice are not easily gredients are synthetic (or designer) detected in standard drug tests. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

MENU DEAR CUSTOMERS, Pakistani Cuisine Is a Mixturedrodzy of South Przyjaciele Asian Culinary Traditions, Characterized by a Large Variety and Richness of Flavours

NEW MENU DEAR CUSTOMERS, Pakistani cuisine is a mixtureDrodzy of South Przyjaciele Asian culinary traditions, characterized by a large variety and richness of flavours. Pakistani dishes vary greatly depending on the region of origin, thus reflecting the ethnic and cultural diversity of the country. All dishes are tasty, full of aromas and spices. The cuisine comes from the culinary traditions of agricultural, hard-working people, which is why it can be fatty and caloric. The Punjabu cuisine is dominated by meat bathed in thick sauces, with the addition of a large amount of aromatic spices, onions, garlic and stewed vegetables. You can dip Naan bread in the sauces or try Pakistani basmati rice. The taste of sauces depends on the composition and variation of the spices (masala) used. Our restaurant serves authentic Pakistani and Indian cuisine. The dishes are prepared by chef Falak Shair. MENU SYMBOLS gluten free hotness vege perfect for kids novelty You can choose between plain naan bread or rice to accompany your main dish. Please be advise that the hotness level can be customized, we also modify the dishes to eliminate the allergens. Please inform us upon ordering. PLEASE DO PAY ATTENTION TO THE HOTNESS OF DISHES, WE USE A MIXTURE OF PAKISTANI CHILLIES, WHICH ORDER A SNACK AND CHOOSE ARE REALLY SPICY! SNACKS A SAUCE TO ACCOMPANY IT 1. ONION BHAJI 6 PCS. 12 PLN 7. FISH PAKORA 7 PCS. 20 PLN Deep fried onion in pea flour batter. Deep fried fish in pea flour batter. 2. GOBI PAKORA 8 PCS. 14 PLN 8. PRAWN PAKORA 8 PCS. -

Cook Around the World

Cook Around the World Traveler and cook Reid Melton's kitchen is a melting pot of flavors and experiences By SARENE WALLACE , NEWS-PRESS CORRESPONDENT, STEVE MALONE / NEWS-PRESS PHOTOS JANUARY 15, 2004 usually of fennel, cumin, fenugreek, mustard and nigella seeds. He mentioned an unrelated walnut tart recipe he discovered during a training session he conducted in Pakistan. From a crowded handmade pottery vase, he pulled out orangewood hand-carved forks from a desert bazaar in Morocco and a spatula from London. He took down his mother's copper pot from a hanging rack. Near it is an Indian metal plate for heating chapatis. He brought the plate (called a tava) from India, where he was a Peace Corps volunteer in the mid-1960s. Before he left on his two-year stay, his mother, Virginia, made sure he had the necessary survival skills: cooking with basic ingredients. "She said, 'There are some things you've got to be able to cook all around the world. You can get butter, eggs and milk, probably, so you've got to be able to cook with those,' " recalled the 60-year-old who moved to Santa Barbara in 1999. His father, Don, was a master with sandwiches, soups and meats. An adventurous cook, his mother was forever exploring other cuisines. But it was egg custard and spinach soufflZˇ that she chose to ready him for the trip. In Central India, he taught the locals his mother's recipes. They, in turn, exposed him to the region's lightly spiced cuisine. While later living in Washington, D.C., Mr. -

Season with Herbs and Spices

Season with Herbs and Spices Meat, Fish, Poultry, and Eggs ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Beef-Allspice,basil, bay leaf, cardamon, chives, curry, Chicken or Turkey-Allspice, basil, bay leaf, cardamon, garlic, mace, marjoram, dry mustard, nutmeg, onion, cumin, curry, garlic, mace, marjoram, mushrooms, dry oregano, paprika, parsley, pepper, green peppers, sage, mustard, paprika, parsley, pepper, pineapple sauce, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. rosemary, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Pork-Basil, cardamom, cloves, curry, dill, garlic, mace, Fish-Bay leaf, chives, coriander, curry, dill, garlic, lemon marjoram, dry mustard, oregano, onion, parsley, pepper, juice, mace, marjoram, mushrooms, dry mustard, onion, rosemary, sage, thyme, turmeric. oregano, paprika, parsley, pepper, green peppers, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Lamb-Basil, curry, dill, garlic, mace, marjoram, mint, Eggs-Basil, chili powder, chives, cumin, curry, mace, onion, oregano, parsley, pepper, rosemary, thyme, marjoram, dry mustard, onion, paprika, parsley, pepper, turmeric. green peppers, rosemary, savory, tarragon, thyme. Veal-Basil, bay leaf, curry, dill, garlic, ginger, mace, marjoram, oregano, paprika, parsley, peaches, pepper, rosemary, sage, savory, tarragon, thyme, turmeric. Vegetables Asparagus-Caraway seed, dry mustard, nutmeg, sesame Broccoli-Oregano, tarragon. seed. Cabbage-Basil, caraway seed, cinnamon,dill, mace, dry Carrots-Chili powder, cinnamon, ginger, mace, marjoram, mustard, -

World Spice Congress 2012

World Spice Congress 2012 Pune, India Confidential – to be distributed only with express permission from presenter Greg Sommerville Director, Procurement Operations Confidential – to be distributed only with express permission from presenter Topic • Why food safety is critical to the US supply chain in spices • Expectations of US consumer companies from suppliers and producing countries – Procurement – Processing – Quality – Supplier rating Confidential – to be distributed only with express permission from presenter Global Food Supply • 13% of the average US family’s food is now imported from over 180 countries around the globe. • 60% of fruits and vegetables and 80% of seafood are now imported. • More than 130,000 foreign facilities registered • Food imports will continue to expand to meet consumer need for more variety, year around availability and lower cost. Confidential – to be distributed only with express permission from presenter China France Albania Turkey Chives Basil Oregano Anise Seed Romania Celery Seed Chervil Rosemary Bay Leaves Spain Coriander Cinnamon/Cassia Fennel Seed Sage Cumin Seed Anise Seed Poland Coriander Marjoram Savory Croatia Fennel Seed Pakistan Paprika Netherlands Poppy Seed Cumin Seed Rosemary Sage Oregano Cumin Seed Rosemary Caraway Seed Thyme Fennel Seed Savory Poppy Seed Red Pepper Canada Saffron Chervil Ginger Tarragon Sage Caraway Seed Thyme Poppy Seed Germany Hungary Oregano Thyme Coriander Dill Weed Paprika Syria Paprika Parsley Mustard Parsley Poppy Seed Anise Seed Parsley Cumin Seed Red Pepper U.S.A -

Caramel Pumpkin Bread

Caramel Pumpkin Bread Prep Time: 20 - 30 minutes Baking Time: 90 minutes Servings: 3 loaves (8” x 4”) INGREDIENTS 2½ sticks unsalted butter 4 cups + 6 Tbl unbleached flour 3¼ cups granulated sugar 2 bags caramel baking chips (11 oz./bag) 1 teaspoon pumpkin pie spice 1 Tbl baking powder 1 teaspoon vanilla extract 1½ teaspoon baking soda 4 eggs ¼ teaspoon salt 1 cup sour cream ¾ cup brown sugar 2 cans pumpkin (15 oz./can) Preheat oven to 275°. Use 1 Tbl of butter to coat three 8” x 4” loaf pans; dust the pans with 2 Tbl flour; set aside. In a large bowl mix together 2 sticks of butter, granulated sugar, pumpkin pie spice and vanilla extract until fluffy (approx. 3-4 minutes). Add eggs, one at a time, mix on low for 1 minute. In a medium bowl, mix together baking powder, baking soda and sour cream. With a rubber spatula fold the sour cream mixture into the butter mixture. Add the pumpkin and mix together with a rubber spatula. Sift 4 cups of the flour and gradually add to the pumpkin mixture while gently stirring by hand . Stir in caramel baking chips and add the mixture to the prepared loaf pans, leaving 1” of space below the top of each pan. In a small bowl combine brown sugar and 4 Tbl of flour; add 3 Tbl of cold butter and smash with fork until mixture resembles wet sand. Spread evenly over the top of the batter in each loaf pan. Bake in 275° oven for 90 minutes. -

Spice Basics

SSpicepice BasicsBasics AAllspicellspice Allspice has a pleasantly warm, fragrant aroma. The name refl ects the pungent taste, which resembles a peppery compound of cloves, cinnamon and nutmeg or mace. Good with eggplant, most fruit, pumpkins and other squashes, sweet potatoes and other root vegetables. Combines well with chili, cloves, coriander, garlic, ginger, mace, mustard, pepper, rosemary and thyme. AAnisenise The aroma and taste of the seeds are sweet, licorice like, warm, and fruity, but Indian anise can have the same fragrant, sweet, licorice notes, with mild peppery undertones. The seeds are more subtly fl avored than fennel or star anise. Good with apples, chestnuts, fi gs, fi sh and seafood, nuts, pumpkin and root vegetables. Combines well with allspice, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, cumin, fennel, garlic, nutmeg, pepper and star anise. BBasilasil Sweet basil has a complex sweet, spicy aroma with notes of clove and anise. The fl avor is warming, peppery and clove-like with underlying mint and anise tones. Essential to pesto and pistou. Good with corn, cream cheese, eggplant, eggs, lemon, mozzarella, cheese, olives, pasta, peas, pizza, potatoes, rice, tomatoes, white beans and zucchini. Combines well with capers, chives, cilantro, garlic, marjoram, oregano, mint, parsley, rosemary and thyme. BBayay LLeafeaf Bay has a sweet, balsamic aroma with notes of nutmeg and camphor and a cooling astringency. Fresh leaves are slightly bitter, but the bitterness fades if you keep them for a day or two. Fully dried leaves have a potent fl avor and are best when dried only recently. Good with beef, chestnuts, chicken, citrus fruits, fi sh, game, lamb, lentils, rice, tomatoes, white beans. -

The 2 Train Journeys of India

Some dishes contain bones, nuts, seeds, gluten, lactose, soya sauce and food colouring. Please inform a member of staff of any dietary requirements or allergies you may have. All dishes are made with natural heat and aroma from Indian spice we are social blends. Each dish has an individual flavour and spice profile. Like, follow and share us Hints of Spice @PatriArtisan / PatriRestaurant GF: Gluten Free VG : Vegan The 2 Train Full Heat with Spice Undertone V : Vegetarian ORDERING GUIDE N : Nuts Intense Spice and Chilli Step 1. Choose your city New Delhi or CALCUTTA order left to right * Moreish - Order 1 dish each from Street Food and Classic. Food Memories journeys ** Hungry - Order 1 dish each from Street Food, Classic and Signature with one extra. Vegan Vegetarian Nuts City Specials *** Very Hungry - Order 1 each from Street Food, Classic, Pairing and two extras. Our food is prepared to authentic Indian Spice Levels and comes as soon as its ready in no particular order. OF INDIa 30.Masala Iced Karma Soda 4.50 East meets West in this dark refreshing Signature Pairing drink made using organic cola mixed Street FoodSmall Plates Grills & More for 2-3 MasterChef Curries for 2-3 with Grills or Curries with tangy chaat masala and black salt for a unforgettable love me tease Classics me twist of favours 1. Old Delhi Pani Puri (4 pcs) 4.95 7. Nawabi Seekh Kabab (3pcs) 6.50 13. Pantry Chicken Curry (GF ) 10.95 21. Bedmi Aloo (VEGAN/ GF) 6.95 Bombs (6 pcs) 6.50 (GF) (4pcs) 8.50 A simple preparation of onions, tomatoes The quintessential roadside curry for the soul, नई दिल्ली स्टेशन cooked fast and furious style inspired by the 31.Nimbu Lemon Soda 4.50 Crispy wheat(VEGAN) balls filled with chick peas and Medium triple minced skewers marinated using spicy and tangy potato curry reduced in a tango chef’s secret spice and herb mix, cooked over moving express trains and simmered with tomato masala and coriander. -

THE SPICE ISLANDS COOKBOOK: Indonesian Cuisine Revealed

THE SPICE ISLANDS COOKBOOK: Indonesian Cuisine Revealed __________________________________________Copyri !" #y Ta"ie Sri $ulandari %&'% 1 ________________________________________________________________ ((()tas"y*indonesian*+ood),o- THE SPICE ISLANDS COOKBOOK: Indonesian Cuisine Revealed __________________________________________Copyri !" #y Ta"ie Sri $ulandari %&'% TABLE OF CONTENTS The Author.................................................................................................................................7 PREFACE....................................................................................................................................8 Indonesian Food Main Ingredients.......................................................................................16 Indonesian Main Kitchen TOOL............................................................................................19 Important spices (The ROOTS, LEAVES, SEEDS and FLOWERS).......................................21 THE ROOTS..............................................................................................................................21 THE LEAVES............................................................................................................................22 THE SEEDS...............................................................................................................................25 THE FLOWERS and LEAVES.................................................................................................28 VEGETABLES in -

The Spice List

THE SPICE LIST brought to you by THE FOOD BASKET THE SPICE LIST pices are a major part of what we do every day at THE FOOD BASKET. Our food is renowned for its flavour – and our specially selected range of spices are the source Sof that flavour. From intense, fiery and pungent to sweet, fruity and floral, to earthy, woody and nutty, and the equally essential sulfury, bitter and sour – we believe we have sourced a unique mix of flavours so that every dish we create has a unique signature. THE SPICE LIST shares all our secrets with you. All our spices are of the highest grade, chosen to bring you a spectrum of aromas covering the widest taste range and the subtlest of tones. Our blends are created from those same high grade spices, combined with herbs, nuts and seaweeds from the best sources we could find. THE FOOD BASKET was inspired by a trip to India by our founder 22 years ago, which you can read about in this booklet. Experience your own round the world taste trip by dropping into our kitchen shop in Barnes, where you can sample some of our delicious recipes. Maybe you will be inspired to try something new for dinner with family and friends tonight… You can also pick up a complimentary sample blend of spices from our kitchen shop – choose from any of those in this list. with warm aromas from THE FOOD BASKET THE SPICE LIST HOT Our range of hot and pungent spices and chilli powders provides a spectrum of intense and fiery flavours to provide a distinct searing signature to every recipe… Bhut Jolokia Kampot Cascabel Korean Chilli Cayenne Malabar Black De Arbol Mustard Seed Galangal Hungarian Paprika Ginger Red Savina Gochugaru Sarawak White Green Serrano Smoked Red Serrano Habanero Tien Tsin Horseradish Urfa Biber Jalapeno Wasabi ALL OUR Spices are of the highest grade, chosen to bring you the widest range of aromas and subtlest of tones.