Arxiv:1711.05765V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Nov 2017 Therefore the Individual Age Estimates Are Effectively Lower Limits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts. -

Hubble 'Cranes' in for a Closer Look at a Galaxy 16 December 2016

Hubble 'cranes' in for a closer look at a galaxy 16 December 2016 died throughout the cosmos. IC 5201 sits over 40 million light-years away from us. As with two thirds of all the spirals we see in the Universe—including the Milky Way—the galaxy has a bar of stars slicing through its center. Provided by NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center IC 5201 sits over 40 million light-years away from us. As with two thirds of all the spirals we see in the universe -- including the Milky Way, the galaxy has a bar of stars slicing through its center. Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA In 1900, astronomer Joseph Lunt made a discovery: Peering through a telescope at Cape Town Observatory, the British-South African scientist spotted this beautiful sight in the southern constellation of Grus (The Crane): a barred spiral galaxy now named IC 5201. Over a century later, the galaxy is still of interest to astronomers. For this image, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope used its Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) to produce a beautiful and intricate image of the galaxy. Hubble's ACS can resolve individual stars within other galaxies, making it an invaluable tool to explore how various populations of stars sprang to life, evolved, and 1 / 2 APA citation: Hubble 'cranes' in for a closer look at a galaxy (2016, December 16) retrieved 28 September 2021 from https://phys.org/news/2016-12-hubble-cranes-closer-galaxy.html This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. -

190 Index of Names

Index of names Ancora Leonis 389 NGC 3664, Arp 005 Andriscus Centauri 879 IC 3290 Anemodes Ceti 85 NGC 0864 Name CMG Identification Angelica Canum Venaticorum 659 NGC 5377 Accola Leonis 367 NGC 3489 Angulatus Ursae Majoris 247 NGC 2654 Acer Leonis 411 NGC 3832 Angulosus Virginis 450 NGC 4123, Mrk 1466 Acritobrachius Camelopardalis 833 IC 0356, Arp 213 Angusticlavia Ceti 102 NGC 1032 Actenista Apodis 891 IC 4633 Anomalus Piscis 804 NGC 7603, Arp 092, Mrk 0530 Actuosus Arietis 95 NGC 0972 Ansatus Antliae 303 NGC 3084 Aculeatus Canum Venaticorum 460 NGC 4183 Antarctica Mensae 865 IC 2051 Aculeus Piscium 9 NGC 0100 Antenna Australis Corvi 437 NGC 4039, Caldwell 61, Antennae, Arp 244 Acutifolium Canum Venaticorum 650 NGC 5297 Antenna Borealis Corvi 436 NGC 4038, Caldwell 60, Antennae, Arp 244 Adelus Ursae Majoris 668 NGC 5473 Anthemodes Cassiopeiae 34 NGC 0278 Adversus Comae Berenices 484 NGC 4298 Anticampe Centauri 550 NGC 4622 Aeluropus Lyncis 231 NGC 2445, Arp 143 Antirrhopus Virginis 532 NGC 4550 Aeola Canum Venaticorum 469 NGC 4220 Anulifera Carinae 226 NGC 2381 Aequanimus Draconis 705 NGC 5905 Anulus Grahamianus Volantis 955 ESO 034-IG011, AM0644-741, Graham's Ring Aequilibrata Eridani 122 NGC 1172 Aphenges Virginis 654 NGC 5334, IC 4338 Affinis Canum Venaticorum 449 NGC 4111 Apostrophus Fornac 159 NGC 1406 Agiton Aquarii 812 NGC 7721 Aquilops Gruis 911 IC 5267 Aglaea Comae Berenices 489 NGC 4314 Araneosus Camelopardalis 223 NGC 2336 Agrius Virginis 975 MCG -01-30-033, Arp 248, Wild's Triplet Aratrum Leonis 323 NGC 3239, Arp 263 Ahenea -

Class I Methanol Masers Toward External Galaxies

CLASS I METHANOL MASERS TOWARD EXTERNAL GALAXIES by Tiege P. McCarthy, B.Sc. Hons Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Natural Sciences University of Tasmania January, 2020 This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying in accor- dance with the Copyright Act 1968 Signed: Tiege P. McCarthy Date: 08/01/2020 ABSTRACT The role extragalactic class I methanol masers play in their host galaxies is currently not well understood. With only a few known examples of these masers to date, inves- tigating their nature is very difficult. However, determining the physical conditions and environments responsible for these masers will provide a useful tool for the study of external galaxies. In this thesis we present over a hundred hours of Australia Tele- scope Compact Array (ATCA) observations aimed at expanding our available sample size, increasing our understanding of the regions in which these masers form,and making comparison with class I methanol emission towards Galactic regions. We present the first detection of 36.2-GHz class I methanol maser emission toward NGC 4945, which is the second confirmed detection of this masing transition and the brightest class I maser region ever detected. This emission is offset from the nucleus of the galaxy and is likely associated with the interface region between the bar and south- eastern spiral arm. Additionally, we report the first detection of the 84.5-GHz class I maser line toward NGC 253, making NGC 253 the only external galaxy displaying 3 separate masing transitions of methanol. -

Survival of Exomoons Around Exoplanets 2

Survival of exomoons around exoplanets V. Dobos1,2,3, S. Charnoz4,A.Pal´ 2, A. Roque-Bernard4 and Gy. M. Szabo´ 3,5 1 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, 9747 AD, Landleven 12, Groningen, The Netherlands 2 Konkoly Thege Mikl´os Astronomical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, E¨otv¨os Lor´and Research Network (ELKH), 1121, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os ´ut 15-17, Budapest, Hungary 3 MTA-ELTE Exoplanet Research Group, 9700, Szent Imre h. u. 112, Szombathely, Hungary 4 Universit´ede Paris, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CNRS, F-75005 Paris, France 5 ELTE E¨otv¨os Lor´and University, Gothard Astrophysical Observatory, Szombathely, Szent Imre h. u. 112, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] January 2020 Abstract. Despite numerous attempts, no exomoon has firmly been confirmed to date. New missions like CHEOPS aim to characterize previously detected exoplanets, and potentially to discover exomoons. In order to optimize search strategies, we need to determine those planets which are the most likely to host moons. We investigate the tidal evolution of hypothetical moon orbits in systems consisting of a star, one planet and one test moon. We study a few specific cases with ten billion years integration time where the evolution of moon orbits follows one of these three scenarios: (1) “locking”, in which the moon has a stable orbit on a long time scale (& 109 years); (2) “escape scenario” where the moon leaves the planet’s gravitational domain; and (3) “disruption scenario”, in which the moon migrates inwards until it reaches the Roche lobe and becomes disrupted by strong tidal forces. -

Cloud Download

ATLAS OF GALAXIES USEFUL FOR MEASURING THE COSMOLOGICAL DISTANCE SCALE .0 o NASA SP-496 ATLAS OF GALAXIES USEFUL FOR MEASURING THE COSMOLOGICAL DISTANCE SCALE Allan Sandage Space Telescope Science Institute Baltimore, Maryland and Department of Physics and Astronomy, The Johns Hopkins University Baltimore, Maryland and John Bedke Computer Sciences Corporation Space Telescope Science Institute Baltimore, Maryland Scientific and Technical Information Division 1988 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Washington, DC Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sandage, Allan. Atlas of galaxies useful for measuring the cosomological distance scale. (NASA SP ; 496) Bibliography: p. 1. Cosmological distances--Measurement. 2. GalaxiesrAtlases. 3. Hubble Space Telescope. I. Bedke, John. II. Title. 111. Series. QB991.C66S36 1988 523.1'1 88 600056 For sale b_ the Superintendent of tX_uments. U S Go_ernment Printing Office. Washington. DC 20402 PREFACE A critical first step in determining distances to galaxies is to measure some property (e.g., size or luminosity) of primary objects such as stars of specific types, H II regions, and supernovae remnants that are resolved out of the general galaxy stellar content. Very few galaxies are suitable for study at such high resolution because of intense disk background light, excessive crowding by contaminating images, internal obscuration due to dust, high inclination angles, or great distance. Nevertheless, these few galaxies with accurately measurable primary distances are required to calibrate secondary distance indicators which have greater range. If telescope time is to be optimized, it is important to know which galaxies are suitable for specific resolution studies. No atlas of galaxy photographs at a scale adequate for resolution of stellar content exists that is complete for the bright galaxy sample [e.g.; for the Shapley-Ames (1932) list, augmented with listings in the Second Reference Catalog (RC2) (de Vaucouleurs, de Vaucouleurs, and Corwin, 1977); and the Uppsala Nilson (1973) catalogs]. -

Radio Continuum Morphology of Southern Seyfert Galaxies?

ASTRONOMY & ASTROPHYSICS JUNE II 1999, PAGE 457 SUPPLEMENT SERIES Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 137, 457–471 (1999) Radio continuum morphology of southern Seyfert galaxies? R. Morganti1, Z.I. Tsvetanov2, J. Gallimore3,??, and M.G. Allen4 1 Istituto di Radioastronomia, CNR, Via Gobetti 101, 40129 Bologna, Italy e-mail: [email protected] 2 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD 21218, U.S.A. 3 NRAO, 520 Edgemont Rd., Charlottesville, VA 22903, U.S.A. 4 Mount Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories, Private Bag, Weston Creek Post Office, ACT 2611, Australia Received October 19, 1998; accepted April 16, 1999 Abstract. We present radio observations for 29 southern 1. Introduction Seyfert galaxies selected from a volume limited sample with cz < 3600 km s−1, and declination δ<0◦. Objects Radio emission from Seyfert galaxies traces energetic, me- with declination −30◦ <δ<0◦ were observed with the chanical processes occurring in the active nucleus. The Very Large Array (VLA) at 6 cm (4.9 GHz) and objects radio continuum spectra of Seyferts are almost invariably with δ<−30◦ were observed with the Australia Telescope steep, consistent with optically-thin synchrotron emission. Compact Array (ATCA) at 3.5 cm (8.6 GHz). Both the In those sources where the radio continuum has been re- VLA and the ATCA observations have a resolution of solved, the morphology is commonly linear, interpreted to ∼ 100. These new observations cover more than 50% of trace a stream of ejected plasma, or a jet, originating from the southern sample with all but two of the 29 objects de- the central engine. -

On the Association Between Core-Collapse Supernovae and HII

MNRAS 428, 1927–1943 (2013) doi:10.1093/mnras/sts145 On the association between core-collapse supernovae and H II regions Paul A. Crowther‹ Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Sheffield, Hicks Building, Hounsfield Road, Sheffield S3 7RH Accepted 2012 October 3. Received 2012 October 3; in original form 2012 August 7 ABSTRACT Previous studies of the location of core-collapse supernovae (ccSNe) in their host galaxies have variously claimed an association with H II regions; no association or an association only with hydrogen-deficient ccSNe. Here, we examine the immediate environments of 39 ccSNe whose positions are well known in nearby (≤15 Mpc), low-inclination (≤65◦) hosts using mostly archival, continuum-subtracted Hα ground-based imaging. We find that 11 out of 29 hydrogen-rich ccSNe are spatially associated with H II regions (38 ± 11 per cent), versus 7 out of 10 hydrogen-poor ccSNe (70 ± 26 per cent). Similar results from Anderson et al. led to an interpretation that the progenitors of Type Ib/c ccSNe are more massive than those of Type II ccSNe. Here, we quantify the luminosities of H II region either coincident with or nearby to the ccSNe. Characteristic nebulae are long-lived (∼20 Myr) giant H II regions rather than short-lived (∼4 Myr) isolated, compact H II regions. Therefore, the absence of an H II region from most Type II ccSNe merely reflects the longer lifetime of stars with 12 M than giant H II regions. Conversely, the association of an H II region with most Type Ib/c ccSNe is due to the shorter lifetime of stars with >12 M stars than the duty cycle of giant H II regions. -

A Abell 21, 20–21 Abell 37, 164 Abell 50, 264 Abell 262, 380 Abell 426, 402 Abell 779, 51 Abell 1367, 94 Abell 1656, 147–148

Index A 308, 321, 360, 379, 383, Aquarius Dwarf, 295 Abell 21, 20–21 397, 424, 445 Aquila, 257, 259, 262–264, 266–268, Abell 37, 164 Almach, 382–383, 391 270, 272, 273–274, 279, Abell 50, 264 Alnitak, 447–449 295 Abell 262, 380 Alpha Centauri C, 169 57 Aquila, 279 Abell 426, 402 Alpha Persei Association, Ara, 202, 204, 206, 209, 212, Abell 779, 51 404–405 220–222, 225, 267 Abell 1367, 94 Al Rischa, 381–382, 385 Ariadne’s Hair, 114 Abell 1656, 147–148 Al Sufi, Abdal-Rahman, 356 Arich, 136 Abell 2065, 181 Al Sufi’s Cluster, 271 Aries, 372, 379–381, 383, 392, 398, Abell 2151, 188–189 Al Suhail, 35 406 Abell 3526, 141 Alya, 249, 255, 262 Aristotle, 6 Abell 3716, 297 Andromeda, 327, 337, 339, 345, Arrakis, 212 Achird, 360 354–357, 360, 366, 372, Auriga, 4, 291, 425, 429–430, Acrux, 113, 118, 138 376, 380, 382–383, 388, 434–436, 438–439, 441, Adhara, 7 391 451–452, 454 ADS 5951, 14 Andromeda Galaxy, 8, 109, 140, 157, Avery’s Island, 13 ADS 8573, 120 325, 340, 345, 351, AE Aurigae, 435 354–357, 388 B Aitken, Robert, 14 Antalova 2, 224 Baby Eskimo Nebula, 124 Albino Butterfly Nebula, 29–30 Antares, 187, 192, 194–197 Baby Nebula, 399 Albireo, 70, 269, 271–272, 379 Antennae, 99–100 Barbell Nebula, 376 Alcor, 153 Antlia, 55, 59, 63, 70, 82 Barnard 7, 425 Alfirk, 304, 307–308 Apes, 398 Barnard 29, 430 Algedi, 286 Apple Core Nebula, 280 Barnard 33, 450 Algieba, 64, 67 Apus, 173, 192, 214 Barnard 72, 219 Algol, 395, 399, 402 94 Aquarii, 335 Barnard 86, 233, 241 Algorab, 98, 114, 120, 136 Aquarius, 295, 297–298, 302, 310, Barnard 92, 246 Allen, Richard Hinckley, 5, 120, 136, 320, 324–325, 333–335, Barnard 114, 260 146, 188, 258, 272, 286, 340–341 Barnard 118, 260 M.E. -

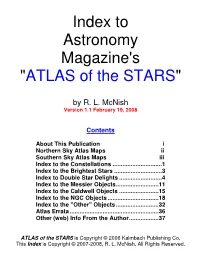

ATLAS of the STARS "

Index to Astronomy Magazine's "ATLAS of the STARS " by R. L. McNish Version 1.1 February 19, 2008 Contents About This Publication i Northern Sky Atlas Maps ii Southern Sky Atlas Maps iii Index to the Constellations ..............................1 Index to the Brightest Stars .............................3 Index to Double Star Delights ..........................4 Index to the Messier Objects..........................11 Index to the Caldwell Objects ........................15 Index to the NGC Objects ...............................18 Index to the "Other" Objects ..........................32 Atlas Errata ......................................................36 Other (web) Info From the Author..................37 ATLAS of the STARS is Copyright © 2006 Kalmbach Publishing Co. This Index is Copyright © 2007-2008, R. L. McNish, All Rights Reserved. About This Publication This Index to Astronomy Magazine's Atlas of the Stars was created to augment the Atlas which was published by Kalmbach Publishing Co. This Index was independently created by close examination of every object identified on all 24 double page maps in the Atlas then combining all the results into the 7 complete indices. Additionally, the author created the diagrams on the next 2 pages to show the overlapping relationships of all the Atlas maps in the Northern and Southern hemispheres of the sky. A page of "Errata" was also added as part of the process. If you find other mistakes in the Atlas I would be interested in noting them in the Errata section. You can send comments to: rascwebmaster [at] shaw [dot] ca . Supporting this Publication and our Centre The Calgary Centre of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (http://calgary.rasc.ca/) is a registered Canadian charitable organization with a very active Public Outreach program. -

Revised Shapley Ames.Pdf

A REVISED SHAPLEY-AMES CATALOG OF BRIGHT GALAXIES The Las Canspanas ridge iii Chile during the last stages of construction of the dome for the du Pont 2.5-meter reflector. The du Pout instrument is at the north end of'thr long escarpment. The Swope 1-meter reflector is in the left foreground. Photu courtesy oi'R, J. Bruuito ; 1*<7*J-. A Revised Shapley-Ames Catalog of Bright Galaxies Containing Data on Magnitudes, Types, and Redshifts for Galaxies in the Original Harvard Survey, Updated to Summer 1980. Also Contains a Selection of Photographs Illustrating the Luminosity Classification and a List of Additional Galaxies that Satisfy the Magnitude Limit of the Original Catalog. Allan Sandage and G. A. Tammann CARNEGIE INSTITUTION OF WASHINGTON PUBLICATION 635 WASHINGTON, D.C. • 198 1 ISBN:0-87U79-<i52-:i Libran oi'CongrrssCatalog Card No. 80-6H146 (JompoMtion. Printing, and Binding by Mmden-Stinehour. Inr. ('<»p\ritiht C ]'M\, (Jariit'^it* Institution nf Washington ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to Miss B. Flach and Mrs. R. C. Kraan- Korteweg for their help in compiling part of the data. We also owe special thanks to Basil Katem for his large effort in de- termining revised coordinates by measurement of National Geo- graphic-Palomar Sky Survey prints and Uppsala Schmidt plates for most of the listed galaxies, and to John Bedke for his skill in reproducing the photographs. We are especially grateful to R. J. Brucato for his important help in obtaining the most recent plates at Las Campanas. We greatly appreciate the help of several observers for provid- ing prepublication redshift data. -

Optical Studies of Star Formation in Normal Spiral Galaxies: Radial Characteristics*

Aust. J. Phys., 1992, 45, 395-405 Optical Studies of Star Formation in Normal Spiral Galaxies: Radial Characteristics* Stuart Ryder Mt Stromlo and Siding Spring Observatories, Australian National University, Private Bag, Weston Creek P.O., A.C.T. 2611, Australia. Abstract First results of a new, homogeneous CCD imaging survey of nearby southern spiral galaxies in V, I and Ha are presented. Elliptical aperture photometry has been used to determine the deprojected surface brightnesses as a function of galactocentric radius, and thus to trace the past and present star formation behaviour. From a sub-sample of nine mainly barred spirals, we find a couple of notable trends. Firstly, nearly all of the barred spirals show evidence of significant levels of ongoing star formation in the bulge, probably fed by gas inflow along the bar. Secondly, the disk Ha profiles are quite shallow compared with the broadband exponential disks, implying a relative insensitivity of the current star formation rate to the surface density of stars already formed. In both the bulge and the disk, the gas consumption timescales are such as to require gas replenishment, e.g. by radial inflow. 1. Introduction A prescription for star formation is one of the major ingredients in any galaxy evolution model. Ideally, it will be able to account for the observed distribution of stars within a galaxy, as well as predict the rate and distribution of star formation in the current epoch. Despite recent advances in optical detectors such as CCDs, there is still a lack of consistent surveys which spatially resolve the various stellar populations in spiral galaxies, and thus of data with which to constrain the competing models of galaxy evolution.