Land, Livelihood and Rana Tharu Identity Transformations in Far- Western Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Nepal

ECONOMIC EMPOWERMENT OF INDIGENOUS WOMEN IN NEPAL Economic Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Nepal National Indigenous Women's Federation United Nations Development (NIWF) Programme (UNDP) in Nepal 2018 First Published in 2018 by: National Indigenous Women's Federation (NIWF) Buddhanagar-10, Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: +977-1- 4784192 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.niwf.org.np/ United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) UN House, Pulchowk, GPO Box: 107 Kathmandu, Nepal Phone : +977 1 5523200 Fax : +977 1 5523991, 5223986 Website: http://www.np.undp.org First Edition: 2018 (500 copies) ISBN: 978 - 9937 - 0 - 4620 - 6 Copyright @ 2018 National Indigenous Women's Federation (NIWF) and UNDP This book may be reproduced in whole or in part in any form for educational, training or nonprofit purposes with due acknowledgment of the source. No use of this publication may be made for sale or other commercial purposes without prior permission in writing of the copyright holder. Printed at: Nebula Printers, Lazimpat Picture of front cover page: Courtsey of Dr. Krishna B. Bhattachan Disclaimer: The views expressed in the book are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP in Nepal. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, our heartfelt gratitude goes to all Indigenous Women, specially Raute women of Dailekh and Dadeldhura, Majhi women of Ramechhap, Tharu women of Bardiya and Saptari, Yakkha women of Sankhuwasabha, and Thakali Women of Mustang, who provided us their precious time and information for the successful completion of this study. Our special thanks go to all other respondents, including the customary leaders, Government officials, and all those people(s) who have provided their help and support, directly or indirectly. -

Livlihood Strategy of Rana Tharu

LIVLIHOOD STRATEGY OF RANA THARU : A CASE STUDY OF GETA VDC OF KAILALI DISTRICT A Thesis Submitted to: Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University, in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of the Master Of Arts (MA) In Rural Development By VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No.: 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No.: 204/068 September 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that the thesis entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District submitted to the Central Department of Rural Development, Tribhuvan University, is entirely my original work prepared under the guidance and supervision of my supervisor Prof Dr. Prem Sharma. I have made due acknowledgements to all ideas and information borrowed from different sources in the course of preparing this thesis. The results of this thesis have not been presented or submitted anywhere else for the award of any degree or for any other purposes. I assure that no part of the content of this thesis has been published in any form be ........................ VIJAYA RAJ JOSHI Central Department of Rural Development Tribhuvan University TU Regd. No. : 6-2-327-108-2008 Roll No : 204/068 Date: August 21, 2016 2073/05/05 . 2 RECOMMENDATION LETTER This is to certify that Mr. Vijaya Raj Joshi has completed this thesis work entitled Livelihood Strategy of Rana Tharu : A Case Study of Geta VDC of Kailali District under my guidance and supervision. I recommend this thesis for final approval and acceptance. _____________________ Prof. Dr. Prem Sharma (Supervisor) Date: Sep 14, 2016 2073/05/29 . -

Kanchanpur District

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Kanchanpur District Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Kanchanpur Volume I Final Report January. 2016 Prepared by: Project Research and Engineering Associates for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID through Rural Access Programme (RAP3). District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates 1 District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates Lagankhel, Lalitpur Phone: 5539607 Email: [email protected] -

The Kamaiya System of Bonded Labour in Nepal

Nepal Case Study on Bonded Labour Final1 1 THE KAMAIYA SYSTEM OF BONDED LABOUR IN NEPAL INTRODUCTION The origin of the kamaiya system of bonded labour can be traced back to a kind of forced labour system that existed during the rule of the Lichhabi dynasty between 100 and 880 AD (Karki 2001:65). The system was re-enforced later during the reign of King Jayasthiti Malla of Kathmandu (1380–1395 AD), the person who legitimated the caste system in Nepali society (BLLF 1989:17; Bista 1991:38-39), when labourers used to be forcibly engaged in work relating to trade with Tibet and other neighbouring countries. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Gorkhali and Rana rulers introduced and institutionalised new forms of forced labour systems such as Jhara,1 Hulak2, Beth3 and Begar4 (Regmi, 1972 reprint 1999:102, cited in Karki, 2001). The later two forms, which centred on agricultural works, soon evolved into such labour relationships where the workers became tied to the landlords being mortgaged in the same manner as land and other property. These workers overtimes became permanently bonded to the masters. The kamaiya system was first noticed by anthropologists in the 1960s (Robertson and Mishra, 1997), but it came to wider public attention only after the change of polity in 1990 due in major part to the work of a few non-government organisations. The 1990s can be credited as the decade of the freedom movement of kamaiyas. Full-scale involvement of NGOs, national as well as local, with some level of support by some political parties, in launching education classes for kamaiyas and organising them into their groups culminated in a kind of national movement in 2000. -

Traditional Phytotherapy of Some Medicinal Plants Used by Tharu and Magar Communities of Western Nepal, Against Dermatological D

TRADITIONAL PHYTOTHERAPY OF SOME MEDICINAL PLANTS USED BY THARU AND MAGAR COMMUNITIES OF WESTERN NEPAL, AGAINST DERMATOLOGICAL DISORDERS Anant Gopal Singh* and Jaya Prakash Hamal** *'HSDUWPHQWRI%RWDQ\%XWZDO0XOWLSOH&DPSXV%XWZDO7ULEKXYDQ8QLYHUVLW\1HSDO ** 'HSDUWPHQWRI%RWDQ\$PULW6FLHQFH&DPSXV7ULEKXYDQ8QLYHUVLW\.DWKPDQGX1HSDO Abstract: (WKQRERWDQ\VXUYH\ZDVXQGHUWDNHQWRFROOHFWLQIRUPDWLRQIURPWUDGLWLRQDOKHDOHUVRQWKHXVHRIPHGLFLQDO SODQWVLQWKHWUHDWPHQWRIGLIIHUHQWVNLQGLVHDVHVVXFKDVFXWVDQGZRXQGVHF]HPDERLOVDEVFHVVHVVFDELHVGRJ DQGLQVHFWELWHULQJZRUPOHSURV\EXUQVEOLVWHUVDOOHUJ\LWFKLQJSLPSOHVOHXFRGHUPDSULFNO\KHDWZDUWVVHSWLF XOFHUVDQGRWKHUVNLQGLVHDVHVLQZHVWHUQ1HSDOGXULQJGLIIHUHQWVHDVRQRI0DUFKWR0D\7KHLQGLJHQRXV NQRZOHGJH RI ORFDO WUDGLWLRQDO KHDOHUV KDYLQJ SUDFWLFDO NQRZOHGJH RI SODQWV LQ PHGLFLQH ZHUH LQWHUYLHZHG LQ YLOODJHVRI5XSDQGHKLGLVWULFWRIZHVWHUQ1HSDODQGQDWLYHSODQWVXVHGIRUPHGLFLQDOSXUSRVHVZHUHFROOHFWHGWKURXJK TXHVWLRQQDLUHDQGSHUVRQDOLQWHUYLHZVGXULQJ¿HOGWULSV$WRWDORISODQWVSHFLHVRIIDPLOLHVDUHGRFXPHQWHGLQ WKLVVWXG\7KHPHGLFLQDOSODQWVXVHGLQWKHWUHDWPHQWRIVNLQGLVHDVHVE\WULEDO¶VDUHOLVWHGZLWKERWDQLFDOQDPH LQ ELQRPLDOIRUP IDPLO\ORFDOQDPHVKDELWDYDLODELOLW\SDUWVXVHGDQGPRGHRISUHSDUDWLRQ7KLVVWXG\VKRZHGWKDW PDQ\SHRSOHLQWKHVWXGLHGSDUWVRI5XSDQGHKLGLVWULFWFRQWLQXHWRGHSHQGRQWKHPHGLFLQDOSODQWVDWOHDVWIRUWKH WUHDWPHQWRISULPDU\KHDOWKFDUH Keywords 7KDUX DQG 0DJDU WULEHV7UDGLWLRQDO NQRZOHGJH 'HUPDWRORJLFDO GLVRUGHUV 0HGLFLQDO SODQWV:HVWHUQ 1HSDO INTRODUCTION fast disappearing due to modernization and the tendency to discard their traditional life style and gradual 7KH NQRZOHGJH -

Causelist Dated:- 05-08-2021

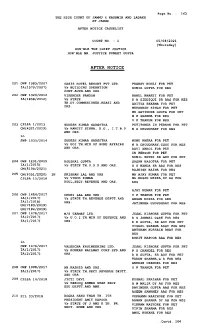

Page No. : 163 THE HIGH COURT OF JAMMU & KASHMIR AND LADAKH AT JAMMU AFTER NOTICE CAUSELIST COURT NO. : 1 05/08/2021 [Thursday] HON'BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE PUNEET GUPTA AFTER NOTICE 201 OWP 1083/2007 OASIS HOTEL RESORT PVT.LTD. PRANAV KOHLI FOR PET IA(1570/2007) Vs BUILDING OPERATION SONIA GUPTA FOR RES CONT.AUTH.AND ORS. 202 OWP 1329/2012 VIRENDER PANDOH RAHUL BHARTI FOR PET IA(1858/2012) Vs STATE H A SIDDIQUI SR AAG FOR RES TH.DY.COMMSSIONER,REASI AND ADITYA SHARMA FOR PET ORS. MEHARBAN SINGH FOR PET MR.SATINDER GUOTA FOR PET M P SHARMA FOR RES O P THAKUR FOR RES 203 CPLPA 1/2013 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA PETITONER IN PERSON FOR PET CM(4321/2019) Vs RANJIT SINHA, D.G., I.T.B.P N A CHOUDHARY FOR RES AND ORS. in SWP 1035/2014 SUDESH KUMAR GARGOTRA NONU KHERA FOR PET Vs UOI TH.MIN.OF HOME AFFAIRS N A CHOUDHARY,CGSC FOR RES AND ORS. RAVI ABROL FOR PET IN PERSON FOR PET SUNIL SETHI SR ADV FOR PET 204 OWP 1231/2015 KOUSHAL GUPTA GAGAN BASOTRA FOR PET IA(1/2015) Vs STATE TH.U.D.D.AND ORS. S S NANDA SR AAG FOR RES CM(5108/2021) RAJNISH RAINA FOR RES 205 CM(6351/2020) IN KRISHAN LAL AND ORS MR.AJAY KUMAR FOR PET CPLPA 15/2016 Vs VINOD KUMAR MR.EHSAN MIRZA,DY.AG FOR KOUL,SECY.REVENUE AND ORS. RES AJAY KUMAR FOR PET 206 OWP 1454/2017 CHUNI LAL AND ORS. -

Castes and Caste Relationships

Chapter 4 Castes and Caste Relationships Introduction In order to understand the agrarian system in any Indian local community it is necessary to understand the workings of the caste system, since caste patterns much social and economic behaviour. The major responses to the uncertain environment of western Rajasthan involve utilising a wide variety of resources, either by spreading risks within the agro-pastoral economy, by moving into other physical regions (through nomadism) or by tapping in to the national economy, through civil service, military service or other employment. In this chapter I aim to show how tapping in to diverse resource levels can be facilitated by some aspects of caste organisation. To a certain extent members of different castes have different strategies consonant with their economic status and with organisational features of their caste. One aspect of this is that the higher castes, which constitute an upper class at the village level, are able to utilise alternative resources more easily than the lower castes, because the options are more restricted for those castes which own little land. This aspect will be raised in this chapter and developed later. I wish to emphasise that the use of the term 'class' in this context refers to a local level class structure defined in terms of economic criteria (essentially land ownership). All of the people in Hinganiya, and most of the people throughout the village cluster, would rank very low in a class system defined nationally or even on a district basis. While the differences loom large on a local level, they are relatively minor in the wider context. -

Disputed Land Rights and Conservation-Led Displacement: a Double Whammy on the Poor

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, July 29, 2014, IP: 129.79.203.179] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 12(1): 65-76, 2014 Article Disputed Land Rights and Conservation-led Displacement: A Double Whammy on the Poor Lai Ming Lama,# and Saumik Paulb aOsaka University, School of Human Sciences, Suita City, Osaka, Japan bUniversity of Nottingham (Malaysia Campus), School of Economics, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia #Corresponding author. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract The practice of conservation through displacement has become commonplace in developing countries. However, resettlement programs remain at very low standards as government policies only focus on economic-based compensation which often excludes socially and economically marginalised groups. In this paper, based on a case study of the displaced indigenous people, the Rana Tharus, from the Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve in Nepal, we argue that compensation as a panacea is a myth as it does not effectively replace the loss of livelihoods. This is particularly the case when the indigenous community’s customary rights to land are not legally protected. Our ethnographic data support the contention that the history of social exclusion is rooted in the land reform and settlement policies, which deprived the Rana Tharus of proper land rights. The present land compensation scheme resulted in a ‘double whammy’ on indigenous forest dwellers. The legal land title holders on average received less than 60% of their land. Moreover, due to the poor quality of soil in the resettlement areas the average crop yield was less than half the quantity produced before displacement. -

Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in a Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F

Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 4 Number 2 Himalayan Research Bulletin, Monsoon Article 7 1984 1984 Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal Walter F. Winkler Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Winkler, Walter F. (1984) "Oral History and the Evolution of Thakuri Political Authority in A Subregion of Far Western Nepal," Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies: Vol. 4: No. 2, Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol4/iss2/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Himalaya, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ... ORAL HISTORY AND THE EVOLUTION OF THAKUR! POLITICAL AUTHORITY IN A SUBREGION OF FAR WESTERN NEPAL Walter F. Winkler Prologue John Hitchcock in an article published in 1974 discussed the evolution of caste organization in Nepal in light of Tucci's investigations of the Malia Kingdom of Western Nepal. My dissertation research, of which the following material is a part, was an outgrowth of questions John had raised on this subject. At first glance the material written in 1978 may appear removed fr om the interests of a management development specialist in a contemporary Dallas high technology company. At closer inspection, however, its central themes - the legitimization of hierarchical relationships, the "her o" as an organizational symbol, and th~ impact of local culture on organizational function and design - are issues that are relevant to industrial as well as caste organization. -

Appendix 1: Reviewed Research on Farmer Knowledge of Soil Fauna in Agricultural Contexts

Appendix 1: Reviewed research on farmer knowledge of soil fauna in agricultural contexts. Table A1.1: List of studies used to compile the worldwide map of reported local farmer knowledge of soil fauna in agricultural contexts (Figure 1) Author Focal Soil Location Description of people and agroecosystem Practical application or underlying motivation of Fauna Taxa‡ study Adjei-Nsiah et al. Earthworms, Village of Asuoano, Wenchi Indigenous Akan people, and migrant Lobi, Wala and Dagaba Explore farmers' soil fertility management practices and their (2004) termites District, Brong-Ahafo region, people. Smallholder farmers with main crops maize, cassava, relevant social context (including comparing migrant farmers Ghana. yam, cocoyam, pigeon pea, plantain, cowpea and groundnut. with local/Indigenous farmers), to ground future action Forest-savannah transitional agro-ecological zone. research in the needs of the local farming community. Ali (2003) Earthworms Damarpota village, floodplain Smallholder saline wet rice ecosystem; tropical monsoon Quantifying farmers’ knowledge and comparing with scientific of the Betravati (Betna) river, climate with three cropping seasons. Main crops three data to provide evidence that farmers’ substantial knowledge southwestern Bangladesh varieties of rice, plus jute, vegetables and oilseeds. should be used in agricultural development policies and in national scientific databases. Atwood (2010) Multiple ‘Thumb’ region of Michigan Family farms growing multiple crops including soybeans, Compare and characterise the worldviews of organic and state (Huron, Sanilac, Tuscola corn, sugarbeets, dry beans, and winter wheat, with some non-organic farmers through their observations of crop and and Lapeer counties), USA livestock soil health, perceptions of soil quality indicators and agricultural management information channels. Audeh et al. -

(2016), Volume 4, Issue 1, 1143- 1149

ISSN 2320-5407 International Journal of Advanced Research (2016), Volume 4, Issue 1, 1143- 1149 Journal homepage: http://www.journalijar.com INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ADVANCED RESEARCH RESEARCH ARTICLE Tribes of Uttar Pradesh, Brief Introduction Ramesh Kumar Rai Research Scholar in O.P.J.S.University ,Churu, Rajsthan.research on topic“The Political Empowerment of Scheduled Tribes Communities in Uttar Pradesh “(A Study of Gond and Kharwar Tribes), Manuscript Info Abstract Manuscript History: The Paper highlights Briefly socio - economic conditions with historical backgrounds of tribal communities inhabit in Uttar Pradesh. As regarded Received: 15 November 2015 Final Accepted: 22 December 2015 tribes are aborigines of country and are also inhabited in Uttar Pradesh for a Published Online: January 2016 long period. Every tribes in this state related with kingdoms in past, they are owner of caltural, social and religious heritage but now they are struggling Key words: for their cultural, political and social identity, they have lost their identity and Tribes, Community, also pride.Their cultural and social aspect are differents but their economical Literacy, Livlihood. status are same. They live in poverty, depend on forest produce,agriculture and non regular works. *Corresponding Author Ramesh Kumar Rai. Copy Right, IJAR, 2016,. All rights reserved. Introduction:- Uttar Pradesh has an immemorial culture, historical background and centre of religious faith therefore, state sustained a different status in Country. Specially after independence Uttar Pradesh has been an axis of politics in Country. Various tribes inhabitant in Uttar Pradesh. As per 1871 census total population of Central India and Bundel Khand were 7699502, total population of North - West Provinces were 31688217, total population of Oudh Provinces was 11220232 and total population of Central provinces was 9251299 (Census 1871). -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894).