Task Force Report -- Preliminary Draft for Public Comment -- 10-22-2020.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Campus Security Report

Campus Security Report 2020 Campus Security Report 2020 Content Message from the Chief…………………………………………………………………………...4 Important Phone Numbers…………………………………………………………………….….5 The Clery Act – Legal Requirements…………………………………………………………....6 Wake Tech Campus Police & Security Services Division: Who We Are………………....7 Our Mission and Core Values…………………………………………………………………….7 Campus Security and Interagency Cooperation……………………………………………...8 Reporting Criminal Incidents, Emergencies and Violent or Threatening Behavior........8 Monitoring and Recording Criminal Activity at Satellite Locations…………………….…10 Annual Fire Safety Report and Missing Student Policy………………………………….….10 Access to Campus Facilities………………………………………………………………….….10 Security Considerations in the Maintenance of Campus Facilities……………….………10 Campus Lighting and Landscape Control Physical security and emergency phones Alerting Wake Tech Community…………………………………………………………………10 Wake Tech Warn Timely Warning Notices Immediate Notifications Emergency Response and Evacuation Procedures…………………………………………11 Testing Evacuation Procedures Evacuation Procedures Evacuation procedures for people with disabilities Evacuation procedures for people with blindness or visual impairment Evacuation procedures for people with hearing disabilities Crime Log……………………………………………………………………………………………13 Crime Prevention Education Awareness………………………………………………………13 Preventing crime through collaboration and cooperation College fire prevention information Crime prevention and safety initiatives Campus escort program Security -

Chapter 74G. Campus Police Act. § 74G-1. Title. This Chapter Is the "Campus Police Act" and May Be Cited by That Name

Chapter 74G. Campus Police Act. § 74G-1. Title. This Chapter is the "Campus Police Act" and may be cited by that name. (2005-231, s. 1.) § 74G-2. Policy and scope. (a) The purpose of this Chapter is to protect the safety and welfare of students, faculty, and staff in institutions of higher education by fostering integrity, proficiency, and competence among campus police agencies and campus police officers. To achieve this purpose, the General Assembly finds that a Campus Police Program needs to be established. As part of the Campus Police Program, the Attorney General is given the authority to certify a private, nonprofit institution of higher education, other than those described by G.S. 116-15(d), as a campus police agency and to commission an individual as a campus police officer. (b) The purpose of this Chapter is also to assure, to the extent consistent with the State and federal constitutions, that this protection is not denied to students, faculty, and staff at private, nonprofit institutions of higher education originally established by or affiliated with religious denominations. To achieve this purpose, the General Assembly finds that: (1) Most of the State's private, nonprofit institutions of higher education were originally established by or affiliated with religious denominations; (2) These institutions have made and continue to make significant contributions in education to the State and the nation; (3) These institutions admit students regardless of their spiritual or religious beliefs; (4) These institutions' principal -

Table of Contents

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Office of the Chief of Police ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Norfolk State University Police Department ............................................................................................................. 3 Law Enforcement Authority and Interagency Cooperation .................................................................................... 4 Campus Security .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Training ........................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access to the Campus Facilities .................................................................................................................................. 6 Special Procedures for Residence Halls ..................................................................................................................... 6 Visitation....................................................................................................................................................................... 8 Fire/Drill/Evacuation Procedure ................................................................................................................................ 9 Security Considerations in Maintenance of Campus Facilities -

Campus Special Constables in Ontario

CAMPUS SPECIAL CONSTABLES in Ontario GEORGE S. RIGAKOS, PhD Ontario Association of College and University Security Administrators Professor of the Political L'Association Des Chefs De Securite Dans Les Colleges Et Universites De L'Ontario Economy of Policing Carleton University OACUSA ACSCUO & SAMANTHA PONTING, MA Comments or Questions to: George S. Rigakos Professor of the Political Economy of Policing Carleton University 613-520-2600 ext. 3683 [email protected] Table of Contents 1.0 Goals and scope of this report 5 2.0 Origins of the office of special constable 7 3.0 Special constables in Canada 9 3.1 Special constables on Canadian campuses 9 3.2 Authority and oversight of campus special constables 10 4.0 Ontario campus special constables 13 4.1 Training, qualifications and accountability 13 4.2 Use of force 14 4.3 Arrest, search and seizure 15 4.4 Oversight 15 5.0 Policing the university community 17 5.1 Specialized campus-based training 17 5.1.1 Theft 19 5.1.2 Sexual assault and violence against women 19 5.1.3 Mental health 22 5.1.4 Substance abuse 22 5.2 Community policing initiatives 23 6.0 The special constable advantage 27 6.1 Special constables as a cost-saving measure 27 6.2 Critical incident response 29 6.3 Specialized service delivery and innovation 30 6.4 Ethical diversion 31 6.5 Information sharing with police 32 Conclusions: Moving Forward 35 APPENDIX 37 Notes 47 GOALS AND SCOPE OF THIS REPORT | 5 Goals and scope of this report 1.0 his study of Ontario Campus Special Constables is undertaken by George S. -

Re-Imagining Campus Safety at Brandeis University Margolis Healy and Associates, Llc, in Association with Brenda Bond-Fortier, Ph.D

RE-IMAGINING CAMPUS SAFETY AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY MARGOLIS HEALY AND ASSOCIATES, LLC, IN ASSOCIATION WITH BRENDA BOND-FORTIER, PH.D. APRIL 21, 2021 MARGOLIS HEALY AND ASSOCIATES RE-IMAGINING CAMPUS SAFETY AT BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY APRIL 21, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION I – INTRODUCTION AND PROJECT SCOPE ....1 Supporting Theme 4.2: Develop and Implement Organization of this Report ....................................1 a Bias-Free Policing Policy and Supporting Procedures ...................................................................44 Acknowledgements ...............................................2 Supporting Theme 4.3: Enhance Transparency of Disclaimer and Disclosure ..................................................2 Training Programs .......................................................54 Methodology ........................................................2 Supporting Theme 4.4: Staffng Considerations to Support Recommendations in this Report ...............55 SECTION II – THE CONTEXT AND NATIONAL DIALOGUE ON ELIMINATING SYSTEMIC RACISM IN POLICING ....4 SECTION V – ATTACHMENTS .....................................60 SECTION III – EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.........................8 Attachment 1: Forum Interview Summary ................60 Attachment 2: PSMS Interview Summary.................61 SECTION IV – MAJOR THEMES ..................................13 Attachment 3: Re-Imagining Campus Safety Major Theme 1.0: Achieve Institutional Consensus Project Summaries ................................................62 on Role, Mission and Values -

Task Force Membership

TASK F ORCE M EMBERSHIP • Michael Boxler - Special Agent in Charge, Kansas City Field Division, Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explo- sives (ATF), Lee's Summit • Kyle Brenneman - Dean of Student Development, Hannibal LaGrange College, Hannibal • Nancy Bush - Center for Emergency Response and Terrorism Director, Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services, Jefferson City • Lynn Carter - Deputy Director, Missouri Department of Mental Health, Jefferson City • David Fedder - Partner, Bryan Cave LLP Law Firm; Commis- sioned Reserve Police Officer, Chesterfield Police Department, St. Louis • Paul Fennewald - Homeland Security Coordinator, Missouri Department of Public Safety, Jef- ferson City • Kevin French - Director of Safety and Security, Drury University, Springfield • Henry Givens - President, Harris-Stowe State University, St. Louis • Van Godsey - Director, Missouri Information Analysis Center, Jefferson City • Clarence Green - Director of Campus Safety, Northwest Missouri State University, Maryville • Matthew Headrick - Student, University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg • James Hughes - Chief of Kirksville Police Department, Kirksville • Mark James – Director, Department of Public Safety (Co-Chair), Jefferson City • John Jordan - Cape Girardeau County Sheriff, Jackson • James Keathley - Superintendent, Missouri State Highway Patrol, Jefferson City • John Kraemer - Associate Professor, Southeast Missouri State University, Cape Girardeau • Thomas Malecek - Director of Corporate Security, Brown Shoe Company, Town & Country • Ron Olinger - Vice President of Financial Planning and Administration, Missouri Western State University, St. Joseph • Mark Potratz - Director of Public Safety, Mineral Area College, Park Hills • Gary Snavely - Director of Safety and Transportation, Missouri State University, Springfield • Robert Stein – Commissioner, Department of Higher Education (Co-Chair), Jefferson City • Brian Stewart – CEO, Bryan College, Springfield • Don Strom - Chief of Police for Washington University, St. -

Annual Security & Fire Safety Report

ANNUAL SECURITY & FIRE SAFETY REPORT In compliance with the JEANNE CLERY DISCLOSURE OF CAMPUS SECURITY POLICY AND CAMPUS CRIME STATISTICS ACT ANNUAL REPORT 2017 GALLOWAY CAMPUS • CARNEGIE CENTER • KRAMER HALL STOCKTON UNIVERSITY AT MANAHAWKIN • WOODBINE SITE EMERGENCY POLICE – FIRE – AMBULANCE DIAL 9-1-1 MAIN CAMPUS POLICE NON-EMERGENCY On Campus ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ Ext� 4390 Off Campus ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������609-652-4390 MAIN CAMPUS POLICE ADMINISTRATION On Campus ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ Ext� 4378 Off Campus ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������609-652-4378 Office of the Dean of Students Ext. 4645 or 609-652-4645 Office of Residential Life Ext. 4332 or 609-652-4332 Health Services Ext. 4701 or 609-652-4701 Counseling Center Ext. 4722 or 609-652-4722 stockton�edu/police stockton�edu/sapublications The following information is published by Stockton University Department of Police “Protecting, Serving and Educating America’s Future” & Division of Student Affairs OCTOBER 1, 2017 A MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF OF POLICE On behalf of the Stockton University Police Department, I would like to welcome you to our diverse and distinctive community. Stockton University is committed to providing a safe and secure environment for our students, faculty, staff and visitors where educational opportunities can thrive. This -

Campus Police Department Manual

Pittsburgh Technical College Campus Police Manual Revised April 21, 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 6 Police Department Mission .............................................................................. 6 Authority ......................................................................................................... 6 Contacting the Department ............................................................................. 6 Personnel ........................................................................................................ 7 PURPOSE AND SCOPE/ SECURITY MANAGEMENT PLANNING .............................. 8 General Security .............................................................................................. 8 Daily Operations Log Book ............................................................................... 9 Responses ........................................................................................................ 9 Security Considerations in the Maintenance of Campus Facilities .................... 9 Access to Housing for Internal and Vendor personnel .................................... 10 Memorandum of Understanding, and interagency cooperation ..................... 10 GENERAL HEALTH AND SAFETY ......................................................................... 10 Emergency Poles and Blue Lights ................................................................... 10 Hospital Transportation -

Final Report of the Campus Safety and Policing Workstream

CAMPUS SAFETY AND POLICING WORKSTREAM —FINAL REPORT— Tufts as an Anti-Racist Institution FEBRUARY 2021 Table of Contents I. Introduction 2 II. Vision 3 III. Principles and Values 4 IV. Recommendations 5 V. Next Steps 10 VI. Appendices 11 A. Working Group Membership 11 B. Charge to the Working Group 12 C. References 13 D. Community Outreach and Input 15 E. Institutional Research Survey Results 16 F. Petitions and Demands 18 G. Arming Status and Considerations 39 I. Introduction On June 19, 2020, also known as Juneteenth, President Anthony Monaco made a commitment to making Tufts an anti-racist institution. During this day, the Tufts community came together and explored the profound effect structural racism has had on Black colleagues and students across our campuses and discussed how we can become a more equitable university moving forward. As a result of these reflections and commitment, a strategic initiative was created to find and eradicate structural racism at Tufts and to take the steps necessary to become an institution that every member of our community would view as anti-racist. This initiative includes five workstreams including the Working Group on Campus Safety and Policing (WGCSP). The WGCSP was established as a university-wide group, with representation from all campuses and membership from the faculty, staff, and graduate and undergraduate student bodies. (see Appendix A) The WGCSP was charged to evaluate the current campus safety and policing model and recommend changes, identify immediate- and long-term objectives, and develop a framework to remain responsive to our community needs. (For complete charge, see Appendix B) The WGCSP has met on average twice weekly since early September to examine internal and external resources, review research studies (Appendix C), meet with experts, and deliberate on a number of topics. -

State and Local Law Enforcement Training Academies, 2006 by Brian A

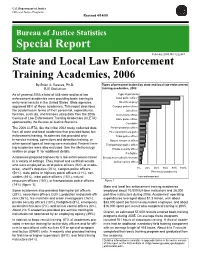

U.S. Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs Revised 4/14/09 Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report February 2009, NCJ 222987 State and Local Law Enforcement Training Academies, 2006 By Brian A. Reaves, Ph.D. Types of personnel trained by state and local law enforcement BJS Statistician training academies, 2006 As of yearend 2006 a total of 648 state and local law Type of personnel enforcement academies were providing basic training to Local police officer entry-level recruits in the United States. State agencies Sheriff's deputy* approved 98% of these academies. This report describes Campus police officer the academies in terms of their personnel, expenditures, Jail officer facilities, curricula, and trainees using data from the 2006 Corrections officer Census of Law Enforcement Training Academies (CLETA) State police officer sponsored by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Constable The 2006 CLETA, like the initial 2002 study, collected data Parole/probation officer from all state and local academies that provided basic law Fire marshal/investigator enforcement training. Academies that provided only Tribal police officer in-service training, corrections and detention training, or Natural resources officer other special types of training were excluded. Federal train- Transportation police officer ing academies were also excluded. See the Methodology Private security officer section on page 11 for additional details. Firefighter Academies prepared trainees for a law enforcement career Emergency medical technician in a variety of settings. They trained and certified recruits Animal control officer who were employed as local police officers (92% of acade- mies), sheriff’s deputies (70%), campus police officers 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% (50%), state police or highway patrol officers (21%), con- Percent of academies stables (16%), tribal police officers (15%), natural *Law enforcement resources officers (15%), or transportation police officers Figure 1 (14%) (figure 1). -

Emergency and Public Safety Contact Information for Stateside Civilian Locations

Emergency and Public Safety Contact Information for Stateside Civilian Locations Anne Arundel Community College at Arundel Mills • For emergencies or to report a crime, call 911 or the Anne Arundel County Police Department at 410-222-8610. • For an escort or to reach AACC Department of Public Safety call 410-777-1818. • To receive text alerts for emergencies, severe weather alerts, and school closings, please sign up for the AACC emergency notification system. • AACC Public Safety hours of operation: Daily, 7 a.m.-11 p.m. • More information: Anne Arundel Community College Public Safety Cecil College • For emergencies or to report a crime, call 911 or the Cecil County Sheriff’s Office at 410-392-2113. • For an escort or to reach Cecil College (North East Campus) Department of Public Safety call 410-287-1601. • To receive text alerts for emergencies, severe weather alerts, and school closings, please sign up for the Cecil College emergency notification system. • More information: Cecil College Department of Public Safety. Dorsey Station • For emergencies or to report a crime, call 911 or the Howard County Police Department at 410-313-2200. • To receive text alerts for emergencies, severe weather alerts, crime alerts, and school closings, please sign up for the UMGC emergency notification system or the Howard County emergency notification system. • Dorsey Station main office: 443-459-3500. • More information: UMGC Security Eastern Shore Higher Education Center • For emergencies or to report a crime, call 911 or the Talbot County Sheriff's Office at 410-822-1020. • To reach Chesapeake College Campus Security, call 410-758-7275 or dial 0 on any campus phone. -

Campus Security Officer Program

CAMPUS SECURITY OFFICER PROGRAM MODULE II. LEGAL AND LIABILITY ISSUES Module II. Student Guide Module II. Goal The goal of Module II is to introduce Campus Security Officer (CSO) to legal and liability issues related to campus security including CSO authority; search and seizure; use of force; legal rights, relationships, and responsibilities in a campus environment; and key state and federal laws with which institutions of higher learning must comply. NOTE: It is critically important for CSOs to understand the policies and procedures established by their colleges or universities related to authority, detainment, search and seizure, use of force. Your department’s policy takes precedence over the general guidelines given in this course. Module II. Topics A. Basis and Parameters of CSO Authority Required Readings: Authorities, Arrest, Search, and Use of Force SAMPLE Guidelines on Pursuit, Use of Force, and Efforts to Detain B. Rights, Relationships, and Responsibilities on Campus Required Readings: Rights, Relationships, and Responsibilities on Campus SAMPLE Policy: Student Rights and Responsibilities C. Key Federal Laws Required Readings: Summary of the Clery Act and Campus Sexual Assault Victims’ Bill of Rights NEWS ARTICLE- Eastern Michigan University Clery Act Fine FERPA and Other Privacy-Related Laws Additional Reading: Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) Brochure Required Assignments Understanding Your Authority CSO will identify the basis of his authority and parameters of authority related to arrest, search, and use of force by examining related policies and procedures of his employing/ contracting institution. Rights and Responsibilities in the Campus Environment: Identifying CSO Roles CSO will identify the roles he or she plays in a) helping his employing/contracting institution exercise “reasonable care” to keep students (and others) safe by identifying and responding to risks and b) implementing college/university disciplinary policy.