Caenorhabditis Elegans As a Model for Lysosomal Storage Disorders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

Transcriptome Sequencing and Genome-Wide Association Analyses Reveal Lysosomal Function and Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 563–572 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/15 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Transcriptome sequencing and genome-wide association analyses reveal lysosomal function and actin cytoskeleton remodeling in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder Z Zhao1,6,JXu2,6, J Chen3,6, S Kim4, M Reimers3, S-A Bacanu3,HYu1, C Liu5, J Sun1, Q Wang1, P Jia1,FXu2, Y Zhang2, KS Kendler3, Z Peng2 and X Chen3 Schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) are severe mental disorders with high heritability. Clinicians have long noticed the similarities of clinic symptoms between these disorders. In recent years, accumulating evidence indicates some shared genetic liabilities. However, what is shared remains elusive. In this study, we conducted whole transcriptome analysis of post-mortem brain tissues (cingulate cortex) from SCZ, BPD and control subjects, and identified differentially expressed genes in these disorders. We found 105 and 153 genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD, respectively. By comparing the t-test scores, we found that many of the genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD are concordant in their expression level (q ⩽ 0.01, 53 genes; q ⩽ 0.05, 213 genes; q ⩽ 0.1, 885 genes). Using genome-wide association data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, we found that these differentially and concordantly expressed genes were enriched in association signals for both SCZ (Po10 − 7) and BPD (P = 0.029). To our knowledge, this is the first time that a substantially large number of genes show concordant expression and association for both SCZ and BPD. Pathway analyses of these genes indicated that they are involved in the lysosome, Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis, regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathways, along with several cancer pathways. -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

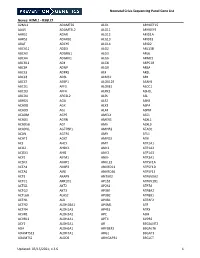

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Sporadic Autism Exomes Reveal a Highly Interconnected Protein Network of De Novo Mutations

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature10989 Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations Brian J. O’Roak1,LauraVives1, Santhosh Girirajan1,EmreKarakoc1, Niklas Krumm1,BradleyP.Coe1,RoieLevy1,ArthurKo1,CholiLee1, Joshua D. Smith1, Emily H. Turner1, Ian B. Stanaway1, Benjamin Vernot1, Maika Malig1, Carl Baker1, Beau Reilly2,JoshuaM.Akey1, Elhanan Borenstein1,3,4,MarkJ.Rieder1, Deborah A. Nickerson1, Raphael Bernier2, Jay Shendure1 &EvanE.Eichler1,5 It is well established that autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have a per generation, in close agreement with our previous observations4, strong genetic component; however, for at least 70% of cases, the yet in general, higher than previous studies, indicating increased underlying genetic cause is unknown1. Under the hypothesis that sensitivity (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4)7. de novo mutations underlie a substantial fraction of the risk for We also observed complex classes of de novo mutation including: five developing ASD in families with no previous history of ASD or cases of multiple mutations in close proximity; two events consistent related phenotypes—so-called sporadic or simplex families2,3—we with paternal germline mosaicism (that is, where both siblings con- sequenced all coding regions of the genome (the exome) for tained a de novo event observed in neither parent); and nine events parent–child trios exhibiting sporadic ASD, including 189 new showing a weak minor allele profile consistent with somatic mosaicism trios and 20 that were previously reported4. Additionally, we also (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figs 2 and 3). sequenced the exomes of 50 unaffected siblings corresponding to Of the severe de novo events, 28% (33 of 120) are predicted to these new (n 5 31) and previously reported trios (n 5 19)4, for a truncate the protein. -

Supplementary Table 1 Genes Tested in Qrt-PCR in Nfpas

Supplementary Table 1 Genes tested in qRT-PCR in NFPAs Gene Bank accession Gene Description number ABI assay ID a disintegrin-like and metalloprotease with thrombospondin type 1 motif 7 ADAMTS7 NM_014272.3 Hs00276223_m1 Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) 3 ARHGEF3 NM_019555.1 Hs00219609_m1 BCL2-associated X protein BAX NM_004324 House design Bcl-2 binding component 3 BBC3 NM_014417.2 Hs00248075_m1 B-cell CLL/lymphoma 2 BCL2 NM_000633 House design Bone morphogenetic protein 7 BMP7 NM_001719.1 Hs00233476_m1 CCAAT/enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), alpha CEBPA NM_004364.2 Hs00269972_s1 coxsackie virus and adenovirus receptor CXADR NM_001338.3 Hs00154661_m1 Homo sapiens Dicer1, Dcr-1 homolog (Drosophila) (DICER1) DICER1 NM_177438.1 Hs00229023_m1 Homo sapiens dystonin DST NM_015548.2 Hs00156137_m1 fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 FLT3 NM_004119.1 Hs00174690_m1 glutamate receptor, ionotropic, N-methyl D-aspartate 1 GRIN1 NM_000832.4 Hs00609557_m1 high-mobility group box 1 HMGB1 NM_002128.3 Hs01923466_g1 heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U HNRPU NM_004501.3 Hs00244919_m1 insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 IGFBP5 NM_000599.2 Hs00181213_m1 latent transforming growth factor beta binding protein 4 LTBP4 NM_001042544.1 Hs00186025_m1 microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta MAP1LC3B NM_022818.3 Hs00797944_s1 matrix metallopeptidase 17 MMP17 NM_016155.4 Hs01108847_m1 myosin VA MYO5A NM_000259.1 Hs00165309_m1 Homo sapiens nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 1 NFE2L1 NM_003204.1 Hs00231457_m1 oxoglutarate (alpha-ketoglutarate) -

A Master Autoantigen-Ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A Master Autoantigen-ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases Julia Y. Wang1*, Michael W. Roehrl1, Victor B. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl2* 1 Curandis, New York, USA 2 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Chronic and debilitating autoimmune sequelae pose a grave concern for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Based on our discovery that the glycosaminoglycan dermatan sulfate (DS) displays peculiar affinity to apoptotic cells and autoantigens (autoAgs) and that DS-autoAg complexes cooperatively stimulate autoreactive B1 cell responses, we compiled a database of 751 candidate autoAgs from six human cell types. At least 657 of these have been found to be affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection based on currently available multi-omic COVID data, and at least 400 are confirmed targets of autoantibodies in a wide array of autoimmune diseases and cancer. -

Chemical Agent and Antibodies B-Raf Inhibitor RAF265

Supplemental Materials and Methods: Chemical agent and antibodies B-Raf inhibitor RAF265 [5-(2-(5-(trifluromethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)pyridin-4-yloxy)-N-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl-1-methyl-1H-benzp{D, }imidazol-2- amine] was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma AG and dissolved in solvent ethanol:propylene glycol:2.5% tween-80 (percentage 6:23:71) for oral delivery to mice by gavage. Antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204(4370), phosphoMEK1/2(2338 and 9121)), phospho-cyclin D1(3300), cyclin D1 (2978), PLK1 (4513) BIM (2933), BAX (2772), BCL2 (2876) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Additional antibodies for phospho-ERK1,2 detection for western blot were from Promega (V803A), and Santa Cruz (E-Y, SC7383). Total ERK antibody for western blot analysis was K-23 from Santa Cruz (SC-94). Ki67 antibody (ab833) was from ABCAM, Mcl1 antibody (559027) was from BD Biosciences, Factor VIII antibody was from Dako (A082), CD31 antibody was from Dianova, (DIA310), and Cot antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-373677). For the cyclin D1 second antibody staining was with an Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, A10042) (1:200 dilution). The pMEK1 fluorescence was developed using the Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG second antibody (1:200 dilution).TUNEL staining kits were from Promega (G2350). Mouse Implant Studies: Biopsy tissues were delivered to research laboratory in ice-cold Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) buffer solution. As the tissue mass available from each biopsy was limited, we first passaged the biopsy tissue in Balb/c nu/Foxn1 athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks of age and weighing 22-25g, purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, USA) to increase the volume of tumor for further implantation. -

Supplementary Table 2

Supplementary Table 2. Differentially Expressed Genes following Sham treatment relative to Untreated Controls Fold Change Accession Name Symbol 3 h 12 h NM_013121 CD28 antigen Cd28 12.82 BG665360 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 1 Flt1 9.63 NM_012701 Adrenergic receptor, beta 1 Adrb1 8.24 0.46 U20796 Nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group D, member 2 Nr1d2 7.22 NM_017116 Calpain 2 Capn2 6.41 BE097282 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 6.21 NM_053328 Basic helix-loop-helix domain containing, class B2 Bhlhb2 5.79 NM_053831 Guanylate cyclase 2f Gucy2f 5.71 AW251703 Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily, member 12a Tnfrsf12a 5.57 NM_021691 Twist homolog 2 (Drosophila) Twist2 5.42 NM_133550 Fc receptor, IgE, low affinity II, alpha polypeptide Fcer2a 4.93 NM_031120 Signal sequence receptor, gamma Ssr3 4.84 NM_053544 Secreted frizzled-related protein 4 Sfrp4 4.73 NM_053910 Pleckstrin homology, Sec7 and coiled/coil domains 1 Pscd1 4.69 BE113233 Suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 Socs2 4.68 NM_053949 Potassium voltage-gated channel, subfamily H (eag- Kcnh2 4.60 related), member 2 NM_017305 Glutamate cysteine ligase, modifier subunit Gclm 4.59 NM_017309 Protein phospatase 3, regulatory subunit B, alpha Ppp3r1 4.54 isoform,type 1 NM_012765 5-hydroxytryptamine (serotonin) receptor 2C Htr2c 4.46 NM_017218 V-erb-b2 erythroblastic leukemia viral oncogene homolog Erbb3 4.42 3 (avian) AW918369 Zinc finger protein 191 Zfp191 4.38 NM_031034 Guanine nucleotide binding protein, alpha 12 Gna12 4.38 NM_017020 Interleukin 6 receptor Il6r 4.37 AJ002942 -

Product Information

Product information PLDN, 1-172aa Human, His-tagged, Recombinant, E.coli Cat. No. IBATGP1472 Full name: pallidin NCBI Accession No.: NP_036520 Synonyms: HPS9, PA, PALLID Description: PLDN (Pallidin) may play a role in intracellular vesicle trafficking. It interacts with Syntaxin 13 which mediates intracellular membrane fusion. Several alternatively spliced transcript variants of this gene have been described, but the full-length nature of some of these variants has not been determined. This protein involved in the development of lysosome-related organelles, such as melanosomes and platelet-dense granules. PLDN has been shown to interact with BLOC1S1, STX12, Dysbindin, CNO, BLOC1S2, MUTED and SNAPAP. Recombinant human PLDN protein, fused to His-tag at N-terminus, was expressed in E.coli and purified by using conventional chromatography techniques. Form: Liquid. In 20mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 2mM DTT, 10% glycerol, 100mM NaCl Molecular Weight: 21.9kDa (192aa), confirmed by MALDI-TOF (Molecular weight on SDS-PAGE will appear higher) Purity: > 90% by SDS - PAGE Concentration: 1mg/ml (determined by Bradford assay) 15% SDS-PAGE (3ug) Sequences of amino acids: MGSSHHHHHH SSGLVPRGSH MSVPGPSSPD GALTRPPYCL EAGEPTPGLS DTSPDEGLIE DLTIEDKAVE QLAEGLLSHY LPDLQRSKQA LQELTQNQVV LLDTLEQEIS KFKECHSMLD INALFAEAKH YHAKLVNIRK EMLMLHEKTS KLKKRALKLQ QKRQKEELER EQQREKEFER EKQLTARPAK RM General references: Huang L, et al. (1999). Nat Genet 23 (3): 329–32. Moriyama K., et al. (2002) Traffic 3:666-677 Storage: Can be stored at +4°C short term (1-2 weeks). For long term storage, aliquot and store at -20°C or -70°C. Avoid repeated freezing and thawing cycles. For research use only. This product is not intended or approved for human, diagnostics or veterinary use. -

Supplementary Table 1

Supplementary Table 1. 492 genes are unique to 0 h post-heat timepoint. The name, p-value, fold change, location and family of each gene are indicated. Genes were filtered for an absolute value log2 ration 1.5 and a significance value of p ≤ 0.05. Symbol p-value Log Gene Name Location Family Ratio ABCA13 1.87E-02 3.292 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family unknown transporter A (ABC1), member 13 ABCB1 1.93E-02 −1.819 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter B (MDR/TAP), member 1 Membrane ABCC3 2.83E-02 2.016 ATP-binding cassette, sub-family Plasma transporter C (CFTR/MRP), member 3 Membrane ABHD6 7.79E-03 −2.717 abhydrolase domain containing 6 Cytoplasm enzyme ACAT1 4.10E-02 3.009 acetyl-CoA acetyltransferase 1 Cytoplasm enzyme ACBD4 2.66E-03 1.722 acyl-CoA binding domain unknown other containing 4 ACSL5 1.86E-02 −2.876 acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain Cytoplasm enzyme family member 5 ADAM23 3.33E-02 −3.008 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 23 Membrane ADAM29 5.58E-03 3.463 ADAM metallopeptidase domain Plasma peptidase 29 Membrane ADAMTS17 2.67E-04 3.051 ADAM metallopeptidase with Extracellular other thrombospondin type 1 motif, 17 Space ADCYAP1R1 1.20E-02 1.848 adenylate cyclase activating Plasma G-protein polypeptide 1 (pituitary) receptor Membrane coupled type I receptor ADH6 (includes 4.02E-02 −1.845 alcohol dehydrogenase 6 (class Cytoplasm enzyme EG:130) V) AHSA2 1.54E-04 −1.6 AHA1, activator of heat shock unknown other 90kDa protein ATPase homolog 2 (yeast) AK5 3.32E-02 1.658 adenylate kinase 5 Cytoplasm kinase AK7 -

SNAPAP Antibody Cat

SNAPAP Antibody Cat. No.: XW-8015 SNAPAP Antibody Specifications HOST SPECIES: Chicken SPECIES REACTIVITY: Human, Mouse, Rat IMMUNOGEN: 31-136 TESTED APPLICATIONS: WB SNARE-associated protein Snapin antibody can be used for the detection of SNARE- APPLICATIONS: associated protein Snapin by Western Blot. PREDICTED MOLECULAR 14.9 kDa (calculated) WEIGHT: Properties PURIFICATION: Immunoaffinity Purified CLONALITY: Polyclonal CONJUGATE: Unconjugated PHYSICAL STATE: Liquid BUFFER: Phosphate-Buffered Saline. No preservatives added. CONCENTRATION: 1 mg/mL October 1, 2021 1 https://www.prosci-inc.com/snapap-antibody-8015.html SNAPAP antibody can be stored at 4˚C for short term (weeks). Long term storage should STORAGE CONDITIONS: be at -20˚C. As with all antibodies care should be taken to avoid repeated freeze thaw cycles. Antibodies should not be exposed to prolonged high temperatures. Additional Info OFFICIAL SYMBOL: SNAPIN BLOC1S7, SNAP25BP, SNAPAP, SNARE-associated protein Snapin, Biogenesis of lysosome- related organelles complex 1 subunit 7, BLOC-1 subunit 7, BLOS7, BLOC1S7, ALTERNATE NAMES: SNAREassociated protein Snapin, Synaptosomal-associated protein 25 binding protein, SNAP-associated protein ACCESSION NO.: NP_036569.1 PROTEIN GI NO.: 6912674 GENE ID: 23557 USER NOTE: Optimal dilutions for each application to be determined by the researcher. Background and References FUNCTION: May modulate a step between vesicle priming, fusion and calcium-dependent neurotransmitter release by potentiating the interaction of synaptotagmins with the SNAREs and the plasma-membrane-associated protein SNAP25. Its phosphorylation state BACKGROUND: influences exocytotic protein interactions and may regulate synaptic vesicle exocytosis. May also have a role in the mechanisms of SNARE-mediated membrane fusion in non- neuronal cells (By similarity).