Associated with Spherical Equivalent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aberrant Methylation Underlies Insulin Gene Expression in Human Insulinoma

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18839-1 OPEN Aberrant methylation underlies insulin gene expression in human insulinoma Esra Karakose1,6, Huan Wang 2,6, William Inabnet1, Rajesh V. Thakker 3, Steven Libutti4, Gustavo Fernandez-Ranvier 1, Hyunsuk Suh1, Mark Stevenson 3, Yayoi Kinoshita1, Michael Donovan1, Yevgeniy Antipin1,2, Yan Li5, Xiaoxiao Liu 5, Fulai Jin 5, Peng Wang 1, Andrew Uzilov 1,2, ✉ Carmen Argmann 1, Eric E. Schadt 1,2, Andrew F. Stewart 1,7 , Donald K. Scott 1,7 & Luca Lambertini 1,6 1234567890():,; Human insulinomas are rare, benign, slowly proliferating, insulin-producing beta cell tumors that provide a molecular “recipe” or “roadmap” for pathways that control human beta cell regeneration. An earlier study revealed abnormal methylation in the imprinted p15.5-p15.4 region of chromosome 11, known to be abnormally methylated in another disorder of expanded beta cell mass and function: the focal variant of congenital hyperinsulinism. Here, we compare deep DNA methylome sequencing on 19 human insulinomas, and five sets of normal beta cells. We find a remarkably consistent, abnormal methylation pattern in insu- linomas. The findings suggest that abnormal insulin (INS) promoter methylation and altered transcription factor expression create alternative drivers of INS expression, replacing cano- nical PDX1-driven beta cell specification with a pathological, looping, distal enhancer-based form of transcriptional regulation. Finally, NFaT transcription factors, rather than the cano- nical PDX1 enhancer complex, are predicted to drive INS transactivation. 1 From the Diabetes Obesity and Metabolism Institute, The Department of Surgery, The Department of Pathology, The Department of Genetics and Genomics Sciences and The Institute for Genomics and Multiscale Biology, The Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY 10029, USA. -

Seq2pathway Vignette

seq2pathway Vignette Bin Wang, Xinan Holly Yang, Arjun Kinstlick May 19, 2021 Contents 1 Abstract 1 2 Package Installation 2 3 runseq2pathway 2 4 Two main functions 3 4.1 seq2gene . .3 4.1.1 seq2gene flowchart . .3 4.1.2 runseq2gene inputs/parameters . .5 4.1.3 runseq2gene outputs . .8 4.2 gene2pathway . 10 4.2.1 gene2pathway flowchart . 11 4.2.2 gene2pathway test inputs/parameters . 11 4.2.3 gene2pathway test outputs . 12 5 Examples 13 5.1 ChIP-seq data analysis . 13 5.1.1 Map ChIP-seq enriched peaks to genes using runseq2gene .................... 13 5.1.2 Discover enriched GO terms using gene2pathway_test with gene scores . 15 5.1.3 Discover enriched GO terms using Fisher's Exact test without gene scores . 17 5.1.4 Add description for genes . 20 5.2 RNA-seq data analysis . 20 6 R environment session 23 1 Abstract Seq2pathway is a novel computational tool to analyze functional gene-sets (including signaling pathways) using variable next-generation sequencing data[1]. Integral to this tool are the \seq2gene" and \gene2pathway" components in series that infer a quantitative pathway-level profile for each sample. The seq2gene function assigns phenotype-associated significance of genomic regions to gene-level scores, where the significance could be p-values of SNPs or point mutations, protein-binding affinity, or transcriptional expression level. The seq2gene function has the feasibility to assign non-exon regions to a range of neighboring genes besides the nearest one, thus facilitating the study of functional non-coding elements[2]. Then the gene2pathway summarizes gene-level measurements to pathway-level scores, comparing the quantity of significance for gene members within a pathway with those outside a pathway. -

Research Article Characterization, Tissue Expression, and Imprinting Analysis of the Porcine CDKN1C and NAP1L4 Genes

Hindawi Publishing Corporation Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology Volume 2012, Article ID 946527, 7 pages doi:10.1155/2012/946527 Research Article Characterization, Tissue Expression, and Imprinting Analysis of the Porcine CDKN1C and NAP1L4 Genes Shun Li,1 Juan Li,1 Jiawei Tian,1 Ranran Dong,1 Jin Wei,1 Xiaoyan Qiu,2 and Caode Jiang2 1 School of Life Science, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China 2 College of Animal Science and Technology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China Correspondence should be addressed to Caode Jiang, [email protected] Received 4 August 2011; Revised 25 October 2011; Accepted 15 November 2011 Academic Editor: Andre Van Wijnen Copyright © 2012 Shun Li et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. CDKN1C and NAP1L4 in human CDKN1C/KCNQ1OT1 imprinted domain are two key candidate genes responsible for BWS (Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome) and cancer. In order to increase understanding of these genes in pigs, their cDNAs are characterized in this paper. By the IMpRH panel, porcine CDKN1C and NAP1L4 genes were assigned to porcine chromosome 2, closely linked with IMpRH06175 and with LOD of 15.78 and 17.94, respectively. By real-time quantitative RT-PCR and polymorphism-based method, tissue and allelic expression of both genes were determined using F1 pigs of Rongchang and Landrace reciprocal crosses. The transcription levels of porcine CDKN1C and NAP1L4 were significantly higher in placenta than in other neonatal tissues (P<0.01) although both genes showed the highest expression levels in the lung and kidney of one- month pigs (P<0.01). -

Snps) Distant from Xenobiotic Response Elements Can Modulate Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Function: SNP-Dependent CYP1A1 Induction S

Supplemental material to this article can be found at: http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/content/suppl/2018/07/06/dmd.118.082164.DC1 1521-009X/46/9/1372–1381$35.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/dmd.118.082164 DRUG METABOLISM AND DISPOSITION Drug Metab Dispos 46:1372–1381, September 2018 Copyright ª 2018 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) Distant from Xenobiotic Response Elements Can Modulate Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Function: SNP-Dependent CYP1A1 Induction s Duan Liu, Sisi Qin, Balmiki Ray,1 Krishna R. Kalari, Liewei Wang, and Richard M. Weinshilboum Division of Clinical Pharmacology, Department of Molecular Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (D.L., S.Q., B.R., L.W., R.M.W.) and Division of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics, Department of Health Sciences Research (K.R.K.), Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota Received April 22, 2018; accepted June 28, 2018 ABSTRACT Downloaded from CYP1A1 expression can be upregulated by the ligand-activated aryl fashion. LCLs with the AA genotype displayed significantly higher hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). Based on prior observations with AHR-XRE binding and CYP1A1 mRNA expression after 3MC estrogen receptors and estrogen response elements, we tested treatment than did those with the GG genotype. Electrophoretic the hypothesis that single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) map- mobility shift assay (EMSA) showed that oligonucleotides with the ping hundreds of base pairs (bp) from xenobiotic response elements AA genotype displayed higher LCL nuclear extract binding after (XREs) might influence AHR binding and subsequent gene expres- 3MC treatment than did those with the GG genotype, and mass dmd.aspetjournals.org sion. -

Transcriptome Sequencing and Genome-Wide Association Analyses Reveal Lysosomal Function and Actin Cytoskeleton Remodeling in Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Molecular Psychiatry (2015) 20, 563–572 © 2015 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1359-4184/15 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Transcriptome sequencing and genome-wide association analyses reveal lysosomal function and actin cytoskeleton remodeling in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder Z Zhao1,6,JXu2,6, J Chen3,6, S Kim4, M Reimers3, S-A Bacanu3,HYu1, C Liu5, J Sun1, Q Wang1, P Jia1,FXu2, Y Zhang2, KS Kendler3, Z Peng2 and X Chen3 Schizophrenia (SCZ) and bipolar disorder (BPD) are severe mental disorders with high heritability. Clinicians have long noticed the similarities of clinic symptoms between these disorders. In recent years, accumulating evidence indicates some shared genetic liabilities. However, what is shared remains elusive. In this study, we conducted whole transcriptome analysis of post-mortem brain tissues (cingulate cortex) from SCZ, BPD and control subjects, and identified differentially expressed genes in these disorders. We found 105 and 153 genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD, respectively. By comparing the t-test scores, we found that many of the genes differentially expressed in SCZ and BPD are concordant in their expression level (q ⩽ 0.01, 53 genes; q ⩽ 0.05, 213 genes; q ⩽ 0.1, 885 genes). Using genome-wide association data from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, we found that these differentially and concordantly expressed genes were enriched in association signals for both SCZ (Po10 − 7) and BPD (P = 0.029). To our knowledge, this is the first time that a substantially large number of genes show concordant expression and association for both SCZ and BPD. Pathway analyses of these genes indicated that they are involved in the lysosome, Fc gamma receptor-mediated phagocytosis, regulation of actin cytoskeleton pathways, along with several cancer pathways. -

Supplemental Information

Supplemental information Dissection of the genomic structure of the miR-183/96/182 gene. Previously, we showed that the miR-183/96/182 cluster is an intergenic miRNA cluster, located in a ~60-kb interval between the genes encoding nuclear respiratory factor-1 (Nrf1) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2H (Ube2h) on mouse chr6qA3.3 (1). To start to uncover the genomic structure of the miR- 183/96/182 gene, we first studied genomic features around miR-183/96/182 in the UCSC genome browser (http://genome.UCSC.edu/), and identified two CpG islands 3.4-6.5 kb 5’ of pre-miR-183, the most 5’ miRNA of the cluster (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1 and Seq. S1). A cDNA clone, AK044220, located at 3.2-4.6 kb 5’ to pre-miR-183, encompasses the second CpG island (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). We hypothesized that this cDNA clone was derived from 5’ exon(s) of the primary transcript of the miR-183/96/182 gene, as CpG islands are often associated with promoters (2). Supporting this hypothesis, multiple expressed sequences detected by gene-trap clones, including clone D016D06 (3, 4), were co-localized with the cDNA clone AK044220 (Fig. 1A; Fig. S1). Clone D016D06, deposited by the German GeneTrap Consortium (GGTC) (http://tikus.gsf.de) (3, 4), was derived from insertion of a retroviral construct, rFlpROSAβgeo in 129S2 ES cells (Fig. 1A and C). The rFlpROSAβgeo construct carries a promoterless reporter gene, the β−geo cassette - an in-frame fusion of the β-galactosidase and neomycin resistance (Neor) gene (5), with a splicing acceptor (SA) immediately upstream, and a polyA signal downstream of the β−geo cassette (Fig. -

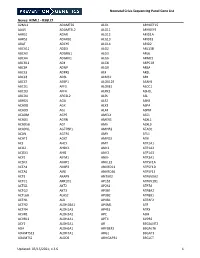

NICU Gene List Generator.Xlsx

Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: A2ML1 - B3GLCT A2ML1 ADAMTS9 ALG1 ARHGEF15 AAAS ADAMTSL2 ALG11 ARHGEF9 AARS1 ADAR ALG12 ARID1A AARS2 ADARB1 ALG13 ARID1B ABAT ADCY6 ALG14 ARID2 ABCA12 ADD3 ALG2 ARL13B ABCA3 ADGRG1 ALG3 ARL6 ABCA4 ADGRV1 ALG6 ARMC9 ABCB11 ADK ALG8 ARPC1B ABCB4 ADNP ALG9 ARSA ABCC6 ADPRS ALK ARSL ABCC8 ADSL ALMS1 ARX ABCC9 AEBP1 ALOX12B ASAH1 ABCD1 AFF3 ALOXE3 ASCC1 ABCD3 AFF4 ALPK3 ASH1L ABCD4 AFG3L2 ALPL ASL ABHD5 AGA ALS2 ASNS ACAD8 AGK ALX3 ASPA ACAD9 AGL ALX4 ASPM ACADM AGPS AMELX ASS1 ACADS AGRN AMER1 ASXL1 ACADSB AGT AMH ASXL3 ACADVL AGTPBP1 AMHR2 ATAD1 ACAN AGTR1 AMN ATL1 ACAT1 AGXT AMPD2 ATM ACE AHCY AMT ATP1A1 ACO2 AHDC1 ANK1 ATP1A2 ACOX1 AHI1 ANK2 ATP1A3 ACP5 AIFM1 ANKH ATP2A1 ACSF3 AIMP1 ANKLE2 ATP5F1A ACTA1 AIMP2 ANKRD11 ATP5F1D ACTA2 AIRE ANKRD26 ATP5F1E ACTB AKAP9 ANTXR2 ATP6V0A2 ACTC1 AKR1D1 AP1S2 ATP6V1B1 ACTG1 AKT2 AP2S1 ATP7A ACTG2 AKT3 AP3B1 ATP8A2 ACTL6B ALAS2 AP3B2 ATP8B1 ACTN1 ALB AP4B1 ATPAF2 ACTN2 ALDH18A1 AP4M1 ATR ACTN4 ALDH1A3 AP4S1 ATRX ACVR1 ALDH3A2 APC AUH ACVRL1 ALDH4A1 APTX AVPR2 ACY1 ALDH5A1 AR B3GALNT2 ADA ALDH6A1 ARFGEF2 B3GALT6 ADAMTS13 ALDH7A1 ARG1 B3GAT3 ADAMTS2 ALDOB ARHGAP31 B3GLCT Updated: 03/15/2021; v.3.6 1 Neonatal Crisis Sequencing Panel Gene List Genes: B4GALT1 - COL11A2 B4GALT1 C1QBP CD3G CHKB B4GALT7 C3 CD40LG CHMP1A B4GAT1 CA2 CD59 CHRNA1 B9D1 CA5A CD70 CHRNB1 B9D2 CACNA1A CD96 CHRND BAAT CACNA1C CDAN1 CHRNE BBIP1 CACNA1D CDC42 CHRNG BBS1 CACNA1E CDH1 CHST14 BBS10 CACNA1F CDH2 CHST3 BBS12 CACNA1G CDK10 CHUK BBS2 CACNA2D2 CDK13 CILK1 BBS4 CACNB2 CDK5RAP2 -

Sporadic Autism Exomes Reveal a Highly Interconnected Protein Network of De Novo Mutations

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature10989 Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations Brian J. O’Roak1,LauraVives1, Santhosh Girirajan1,EmreKarakoc1, Niklas Krumm1,BradleyP.Coe1,RoieLevy1,ArthurKo1,CholiLee1, Joshua D. Smith1, Emily H. Turner1, Ian B. Stanaway1, Benjamin Vernot1, Maika Malig1, Carl Baker1, Beau Reilly2,JoshuaM.Akey1, Elhanan Borenstein1,3,4,MarkJ.Rieder1, Deborah A. Nickerson1, Raphael Bernier2, Jay Shendure1 &EvanE.Eichler1,5 It is well established that autism spectrum disorders (ASD) have a per generation, in close agreement with our previous observations4, strong genetic component; however, for at least 70% of cases, the yet in general, higher than previous studies, indicating increased underlying genetic cause is unknown1. Under the hypothesis that sensitivity (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 4)7. de novo mutations underlie a substantial fraction of the risk for We also observed complex classes of de novo mutation including: five developing ASD in families with no previous history of ASD or cases of multiple mutations in close proximity; two events consistent related phenotypes—so-called sporadic or simplex families2,3—we with paternal germline mosaicism (that is, where both siblings con- sequenced all coding regions of the genome (the exome) for tained a de novo event observed in neither parent); and nine events parent–child trios exhibiting sporadic ASD, including 189 new showing a weak minor allele profile consistent with somatic mosaicism trios and 20 that were previously reported4. Additionally, we also (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Figs 2 and 3). sequenced the exomes of 50 unaffected siblings corresponding to Of the severe de novo events, 28% (33 of 120) are predicted to these new (n 5 31) and previously reported trios (n 5 19)4, for a truncate the protein. -

A Master Autoantigen-Ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. A Master Autoantigen-ome Links Alternative Splicing, Female Predilection, and COVID-19 to Autoimmune Diseases Julia Y. Wang1*, Michael W. Roehrl1, Victor B. Roehrl1, and Michael H. Roehrl2* 1 Curandis, New York, USA 2 Department of Pathology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.07.30.454526; this version posted August 4, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Abstract Chronic and debilitating autoimmune sequelae pose a grave concern for the post-COVID-19 pandemic era. Based on our discovery that the glycosaminoglycan dermatan sulfate (DS) displays peculiar affinity to apoptotic cells and autoantigens (autoAgs) and that DS-autoAg complexes cooperatively stimulate autoreactive B1 cell responses, we compiled a database of 751 candidate autoAgs from six human cell types. At least 657 of these have been found to be affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection based on currently available multi-omic COVID data, and at least 400 are confirmed targets of autoantibodies in a wide array of autoimmune diseases and cancer. -

Chemical Agent and Antibodies B-Raf Inhibitor RAF265

Supplemental Materials and Methods: Chemical agent and antibodies B-Raf inhibitor RAF265 [5-(2-(5-(trifluromethyl)-1H-imidazol-2-yl)pyridin-4-yloxy)-N-(4-trifluoromethyl)phenyl-1-methyl-1H-benzp{D, }imidazol-2- amine] was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma AG and dissolved in solvent ethanol:propylene glycol:2.5% tween-80 (percentage 6:23:71) for oral delivery to mice by gavage. Antibodies to phospho-ERK1/2 Thr202/Tyr204(4370), phosphoMEK1/2(2338 and 9121)), phospho-cyclin D1(3300), cyclin D1 (2978), PLK1 (4513) BIM (2933), BAX (2772), BCL2 (2876) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Additional antibodies for phospho-ERK1,2 detection for western blot were from Promega (V803A), and Santa Cruz (E-Y, SC7383). Total ERK antibody for western blot analysis was K-23 from Santa Cruz (SC-94). Ki67 antibody (ab833) was from ABCAM, Mcl1 antibody (559027) was from BD Biosciences, Factor VIII antibody was from Dako (A082), CD31 antibody was from Dianova, (DIA310), and Cot antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (sc-373677). For the cyclin D1 second antibody staining was with an Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, A10042) (1:200 dilution). The pMEK1 fluorescence was developed using the Alexa Fluor 488 chicken anti-rabbit IgG second antibody (1:200 dilution).TUNEL staining kits were from Promega (G2350). Mouse Implant Studies: Biopsy tissues were delivered to research laboratory in ice-cold Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) buffer solution. As the tissue mass available from each biopsy was limited, we first passaged the biopsy tissue in Balb/c nu/Foxn1 athymic nude mice (6-8 weeks of age and weighing 22-25g, purchased from Harlan Sprague Dawley, USA) to increase the volume of tumor for further implantation. -

Letters to the Editor J Med Genet: First Published As 10.1136/Jmg.37.3.231 on 1 March 2000

210 Letters Letters to the Editor J Med Genet: first published as 10.1136/jmg.37.3.231 on 1 March 2000. Downloaded from J Med Genet 2000;37:210–212 No evidence of germline PTEN three reasons: somatic mutations have been found in PTEN in prostate tumours; germline mutations in Cowden mutations in familial prostate cancer disease produce a phenotype (although with no evidence of an associated susceptibility to prostate cancer); and PTEN deficient mice exhibit prostate abnormalities. We have therefore screened the Cancer Research Campaign/British EDITOR—Prostate cancer is the second most common Prostate Group (CRC/BPG) UK Familial Prostate Cancer cause of male cancer mortality in the UK.1 Current indica- Study samples for evidence of PTEN mutations. tions are that like many common cancers, prostate cancer The CRC/BPG UK Familial Prostate Cancer Study has has an inherited component.2 Segregation analysis has led collected lymphocyte DNA from 188 subjects from 50 to the proposed model of at least one highly penetrant, prostate cancer families. These families were chosen dominant gene (with an estimated 88% penetrance for because each contained three or more cases of prostate prostate cancer by the age of 85 in the highly susceptible cancer at any age or related sib pairs where at least one man population). Such a gene or genes would account for an was less than 67 (original criterion was 65) years old at estimated 43% of cases diagnosed at less than 55 years.2 diagnosis. In fact, the majority of the clusters consist of One prostate cancer susceptibility locus (HPC1) has been aVected sib pairs, with DNA often only available from reported on 1q24-253 and confirmed by Cooney et al4 and cases. -

Mclean, Chelsea.Pdf

COMPUTATIONAL PREDICTION AND EXPERIMENTAL VALIDATION OF NOVEL MOUSE IMPRINTED GENES A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Chelsea Marie McLean August 2009 © 2009 Chelsea Marie McLean COMPUTATIONAL PREDICTION AND EXPERIMENTAL VALIDATION OF NOVEL MOUSE IMPRINTED GENES Chelsea Marie McLean, Ph.D. Cornell University 2009 Epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation and covalent modifications to histone tails, are major contributors to the regulation of gene expression. These changes are reversible, yet can be stably inherited, and may last for multiple generations without change to the underlying DNA sequence. Genomic imprinting results in expression from one of the two parental alleles and is one example of epigenetic control of gene expression. So far, 60 to 100 imprinted genes have been identified in the human and mouse genomes, respectively. Identification of additional imprinted genes has become increasingly important with the realization that imprinting defects are associated with complex disorders ranging from obesity to diabetes and behavioral disorders. Despite the importance imprinted genes play in human health, few studies have undertaken genome-wide searches for new imprinted genes. These have used empirical approaches, with some success. However, computational prediction of novel imprinted genes has recently come to the forefront. I have developed generalized linear models using data on a variety of sequence and epigenetic features within a training set of known imprinted genes. The resulting models were used to predict novel imprinted genes in the mouse genome. After imposing a stringency threshold, I compiled an initial candidate list of 155 genes.