Take Control of Email with Apple Mail 1.1.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes for Mac Driver 3.2

Notes for Mac Driver 3.2 June 26, 2014 General Known Issues 1. Issue: Due to an OS limitation, waste toner status shows as unknown. Solution: Check the device for the actual status of the waste toner. 2. Issue: Output appears pixelated when printing from InDesign CS4. Solution: Adobe recommends placing instead of pasting graphics into InDesign and checking your print settings to make sure graphics are printing properly. In the Graphics section of the Print dialog box, choose Send Data > All. 3. Issue: Error “Incorrect account ID” is displayed on the front panel if printing from QuarkXpress 7.3 or later. Solution: Install Quark® CUPS Filter from Quark’s support website. 4. Issue: Watermark may not print correctly in some devices. Solution: Change the Watermark option from “Transparent” to “Stamp”. 5. Issue: Watermark characters may appear as “◻” when printing some PDF documents. Solution: Use a different font for the Watermark text. 6. Issue: Using both N-up and Watermark/Stamp repeat at the same time may significantly reduce printing speed. Solution: Avoid using both settings at the same time. 7. Issues: Driver constraint information is displayed as a pop-up in some Mac OS X versions. Alert message text is generated by OS. 8. Issue: Paper size name changes in OS X 10.7 (by the OS), “Envelope #6” shows as “Personal” and “Statement” shows as “Invoice”. On minor version up, it appears that “Invoice” was reverted to “Statement”. 9. Issue: Mixed orientation file is treated as separate file when Booklet option is applied. 10. Issue: It is possible for multiple applications to open the Account ID List window at the same time which introduces a race condition where multiple applications are allowed to modify the same Account ID List and one will end up over-writing the other’s changes. -

Mac OS X Includes Built-In FTP Support, Easily Controlled Within a fifteen-Mile Drive of One-Third of the US Population

Cover 8.12 / December 2002 ATPM Volume 8, Number 12 About This Particular Macintosh: About the personal computing experience™ ATPM 8.12 / December 2002 1 Cover Cover Art Robert Madill Copyright © 2002 by Grant Osborne1 Belinda Wagner We need new cover art each month. Write to us!2 Edward Goss Tom Iov ino Editorial Staff Daniel Chvatik Publisher/Editor-in-Chief Michael Tsai Contributors Managing Editor Vacant Associate Editor/Reviews Paul Fatula Eric Blair Copy Editors Raena Armitage Ya n i v E i d e l s t e i n Johann Campbell Paul Fatula Ellyn Ritterskamp Mike Flanagan Brooke Smith Matt Johnson Vacant Matthew Glidden Web E ditor Lee Bennett Chris Lawson Publicity Manager Vacant Robert Paul Leitao Webmaster Michael Tsai Robert C. Lewis Beta Testers The Staff Kirk McElhearn Grant Osborne Contributing Editors Ellyn Ritterskamp Sylvester Roque How To Ken Gruberman Charles Ross Charles Ross Gregory Tetrault Vacant Michael Tsai Interviews Vacant David Zatz Legacy Corner Chris Lawson Macintosh users like you Music David Ozab Networking Matthew Glidden Subscriptions Opinion Ellyn Ritterskamp Sign up for free subscriptions using the Mike Shields Web form3 or by e-mail4. Vacant Reviews Eric Blair Where to Find ATPM Kirk McElhearn Online and downloadable issues are Brooke Smith available at http://www.atpm.com. Gregory Tetrault Christopher Turner Chinese translations are available Vacant at http://www.maczin.com. Shareware Robert C. Lewis Technic a l Evan Trent ATPM is a product of ATPM, Inc. Welcome Robert Paul Leitao © 1995–2002, All Rights Reserved Kim Peacock ISSN: 1093-2909 Artwork & Design Production Tools Graphics Director Grant Osborne Acrobat Graphic Design Consultant Jamal Ghandour AppleScript Layout and Design Michael Tsai BBEdit Cartoonist Matt Johnson CVL Blue Apple Icon Designs Mark Robinson CVS Other Art RD Novo DropDMG FileMaker Pro Emeritus FrameMaker+SGML RD Novo iCab 1. -

Mendeley: Creating Communities of Scholarly Inquiry Through Research Collaboration

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2011 Mendeley: Creating Communities of Scholarly Inquiry Through Research Collaboration Holt Zaugg Brigham Young University - Provo, [email protected] Isaku Tateishi Brigham Young University - Provo Daniel L. Randall BYU Richard E. West BYU Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Zaugg, Holt; Tateishi, Isaku; Randall, Daniel L.; and West, Richard E., "Mendeley: Creating Communities of Scholarly Inquiry Through Research Collaboration" (2011). Faculty Publications. 1633. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/1633 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Mendeley: Creating Communities of Scholarly Inquiry Through Research Collaboration Holt Zaugg Richard E. West Isaku Tateishi Daniel L. Randall Abstract Mendeley is a free, web-based tool for organizing research citations and annotating their accompanying PDF articles. Adapting Web 2.0 principles for academic scholarship, Mendeley integrates the management of the research articles with features for collaborating with researchers locally and worldwide. In this article the features of Mendeley are discussed and critiqued in comparison to other, similar tools. These features include citation management, online synchronization and collaboration, PDF management and annotation, and integration with word processing software. The article concludes with a discussion of how a social networking tool such as Mendeley might impact the academic scholarship process. Keywords: social networking, research, online community, Web 2.0, citation management. -

Podcast Presentation

3/18/2009 Today’s Goals Podcasts: Understanding, 1. What is a podcast? Creating, and Deploying them 2. How do I get podcasts? 3. How do I play podcasts? 4. Why should I care about podcasts for Dr. Rick Jerz ediducation? 5. How do I produce my own audio podcasts? [email protected] 6. How do I deliver (deploy) my own podcasts? www.rjerz.com 1 © 2009 rjerz.com 2 © 2009 rjerz.com Demos 1) What is a Podcast? • It must be nothing, since the “podcast” is not in my dictionary. • It is something only children do. • It has something to do with fishing. • It is a radio talk show. • It a music file. • It is a TV program. • It is a lecture. 3 © 2009 rjerz.com 4 © 2009 rjerz.com Podcast Definition1 Rick’s Podcast Definition • Podcasting is a new format for distributing A method of obtaining (subscribing) audio and video content via the Internet. Actually, podcasting is just multimedia computer files (episodes), usually content enclosed into an RSS file. audio (mp3) or video (m4v), from a • RSS means Really Simple Syndication. RSS is a catalog (RSS feed, XML) on the special format based on XML. In fact, RSS Internet (website), and having them feeds are XML files containing data according to the RSS specification, and usually located automatically delivered to your on a website. computer and then to your iPod (or • XML: an HTML‐like file for handling data. other multimedia player) • HTML: Hyper Text Markup Language 1 ‐ http://www.rss‐specification.com/sitemap.htm 5 © 2009 rjerz.com 6 © 2009 rjerz.com 1 3/18/2009 2) How do I get podcasts? iTunes: An Aggregator -

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC

Business SITUS Address Taxes Owed # 11828201655 PROPERTY HOLDING SERV TRUST 828 WABASH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28208 24.37 1 ROCK INVESTMENTS LLC . 1101 BANNISTER PL CHARLOTTE NC 28213 510.98 1 STOP MAIL SHOP 8206 PROVIDENCE RD CHARLOTTE NC 28277 86.92 1021 ALLEN LLC . 1021 ALLEN ST CHARLOTTE NC 28205 419.39 1060 CREATIVE INC 801 CLANTON RD CHARLOTTE NC 28217 347.12 112 AUTO ELECTRIC 210 DELBURG ST DAVIDSON NC 28036 45.32 1209 FONTANA AVE LLC . FONTANA AV CHARLOTTE 22.01 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1207 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 2896.87 1213 W MOREHEAD STREET GP LLC . 1201 W MOREHEAD ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 6942.12 1233 MOREHEAD LLC . 630 402 CALVERT ST CHARLOTTE NC 28208 1753.48 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BLVD LLC . 1431 E INDEPENDENCE BV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 1352.65 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . HUNTING BIRDS LN MECKLENBURG 444.12 160 DEVELOPMENT GROUP LLC . STEELE CREEK RD MECKLENBURG 2229.49 1787 JAMESTON DR LLC . 1787 JAMESTON DR CHARLOTTE NC 28209 3494.88 1801 COMMONWEALTH LLC . 1801 COMMONWEALTH AV CHARLOTTE NC 28205 9819.32 1961 RUNNYMEDE LLC . 5419 BEAM LAKE DR UNINCORPORATED 958.87 1ST METROPOLITAN MORTGAGE SUITE 333 3420 TORINGDON WY CHARLOTTE NC 28277 15.31 2 THE MAX SALON 10223 E UNIVERSITY CITY BV CHARLOTTE NC 28262 269.96 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 201 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 396.11 201 SOUTH TRYON OWNER LLC 237 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28202 49.80 2010 TRYON REAL ESTATE LLC . 2010 S TRYON ST CHARLOTTE NC 28203 3491.48 208 WONDERWOOD TREE PRESERVATION HO . -

Znetlive SSL Compatible Applications, Platforms & Operating

ZNetLive SSL Compatible Applications, Platforms & Operating Systems Certificate Authority Root Apple MAC OS 9.0+ (circa 2002), includes 10.5.X and 10.6.X Future proof at 2048 bit, embedded in all Microsoft Windows XP, Vista, 7 and 8 (all devices and browsers and capable of upgrading versions inc 32/64 bit) weak encryption to a strong one is the most reliable Certificate Authority Root-GlobalSign. It is very important to ensure a flawless interaction of your online solutions with Default API Support within Hosting Control customers making connection with your web Panels server, reading emails, trusting your e- Ubersmith documents or running your code. Every WHMCS standard machine that uses trust of Public Key Infrastructure (PKI), e.g. S/MIME, SSL/TLS, Document Signing and Code Signing, has GlobalSign’s Root Certification present in it. Email Clients (S/MIME) ZNetLive’s SSL Certificates authenticated by GlobalSign have 2048 bit strength throughout Mulberry Mail complete Digital Certificate portfolio and Microsoft Outlook 99+ comply with recommendations of National Microsoft Entourage (OS/X) Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Qualcomm Eudora 6.2+ according to which all cryptographic keys Mozilla Thunderbird 1.0+ should be 2048 bit strength from 2011 onwards. Mail.app Anything weaker than 2048 bit encryption is Lotus Notes (6+) considered insecure. Because of this, the Netscape Communicator 4.51+ Certification Authorities and Browsers insists The Bat that all the EV SSL Certificates should be 2048 Apple Mail bit encryption. -

Electronic Evidence Examiner

2 Table of Contents About Electronic Evidence Examiner How To .......................................................................12 How to Work with Cases .........................................................................................................13 How to Create New Case .......................................................................................................13 How to Enable Automatic Case Naming .................................................................................14 How to Define Case Name During Automatic Case Creation .................................................14 How to Open Existing Case....................................................................................................15 How to Save Case to Archive .................................................................................................16 How to Change Default Case Location ...................................................................................16 How to Add Data to Case ........................................................................................................17 How to Add Evidence .............................................................................................................18 How to Acquire Devices .........................................................................................................20 How to Import Mobile Data .....................................................................................................21 How to Import Cloud Data ......................................................................................................22 -

View Managing Devices and Corporate Data On

Overview Managing Devices & Corporate Data on iOS Overview Overview Contents Businesses everywhere are empowering their employees with iPhone and iPad. Overview Management Basics The key to a successful mobile strategy is balancing IT control with user Separating Work and enablement. By personalizing iOS devices with their own apps and content, Personal Data users take greater ownership and responsibility, leading to higher levels of Flexible Management Options engagement and increased productivity. This is enabled by Apple’s management Summary framework, which provides smart ways to manage corporate data and apps discretely, seamlessly separating work data from personal data. Additionally, users understand how their devices are being managed and trust that their privacy is protected. This document offers guidance on how essential IT control can be achieved while at the same time keeping users enabled with the best tools for their job. It complements the iOS Deployment Reference, a comprehensive online technical reference for deploying and managing iOS devices in your enterprise. To refer to the iOS Deployment Reference, visit help.apple.com/deployment/ios. Managing Devices and Corporate Data on iOS July 2018 2 Management Basics Management Basics With iOS, you can streamline iPhone and iPad deployments using a range of built-in techniques that allow you to simplify account setup, configure policies, distribute apps, and apply device restrictions remotely. Our simple framework With Apple’s unified management framework in iOS, macOS, tvOS, IT can configure and update settings, deploy applications, monitor compliance, query devices, and remotely wipe or lock devices. The framework supports both corporate-owned and user-owned as well as personally-owned devices. -

Securing Your Email in 13 Steps: the Email Security Checklist Handbook Securing Your Email in 13 Steps

HANDBOOK Securing Your Email in 13 Steps: The Email Security Checklist handbook Securing Your Email in 13 Steps overview You’ve hardened your servers, locked down your website and are ready to take on the internet. But all your hard work was in vain, because someone fell for a phishing email and wired money to a scammer, while another user inadvertently downloaded and installed malware from an email link that opened a backdoor into the network. Email is as important as the website when it comes to security. As a channel for social engineering, malware delivery and resource exploitation, a combination of best practices and user education should be enacted to reduce the risk of an email-related compromise. By following this 13 step checklist, you can make your email configuration resilient to the most common attacks and make sure it stays that way. 2 @UpGuard | UpGuard.com handbook Securing Your Email in 13 Steps 1. Enable SPF How do you know if an email is really from who it says it’s from? There are a couple of ways to answer this question, and Sender Policy Framework (SPF) is one. SPF works by publishing a DNS record of which servers are allowed to send email from a specific domain. 1. An SPF enabled email server receives an email from [email protected] 2. The email server looks up example.com and reads the SPF TXT record in DNS. 3. If the originating server of the email matches one of the allowed servers in the SPF record, the message is accepted. -

Mac OS X Server Administrator's Guide

034-9285.S4AdminPDF 6/27/02 2:07 PM Page 1 Mac OS X Server Administrator’s Guide K Apple Computer, Inc. © 2002 Apple Computer, Inc. All rights reserved. Under the copyright laws, this publication may not be copied, in whole or in part, without the written consent of Apple. The Apple logo is a trademark of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. Use of the “keyboard” Apple logo (Option-Shift-K) for commercial purposes without the prior written consent of Apple may constitute trademark infringement and unfair competition in violation of federal and state laws. Apple, the Apple logo, AppleScript, AppleShare, AppleTalk, ColorSync, FireWire, Keychain, Mac, Macintosh, Power Macintosh, QuickTime, Sherlock, and WebObjects are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc., registered in the U.S. and other countries. AirPort, Extensions Manager, Finder, iMac, and Power Mac are trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. Adobe and PostScript are trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. Java and all Java-based trademarks and logos are trademarks or registered trademarks of Sun Microsystems, Inc. in the U.S. and other countries. Netscape Navigator is a trademark of Netscape Communications Corporation. RealAudio is a trademark of Progressive Networks, Inc. © 1995–2001 The Apache Group. All rights reserved. UNIX is a registered trademark in the United States and other countries, licensed exclusively through X/Open Company, Ltd. 062-9285/7-26-02 LL9285.Book Page 3 Tuesday, June 25, 2002 3:59 PM Contents Preface How to Use This Guide 39 What’s Included -

Apple Has Built a Solution Into Every Mac

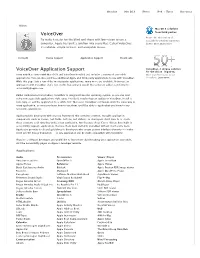

Overview Mac OS X iPhone iPod + iTunes Resources Vision Mac OS X solutions VoiceOver from third parties. Browse the wide variety of To make it easier for the blind and those with low-vision to use a accessibility solutions supported computer, Apple has built a solution into every Mac. Called VoiceOver, by Mac OS X. Learn more it’s reliable, simple to learn, and enjoyable to use. In Depth Device Support Application Support Downloads VoiceOver Application Support VoiceOver. A unique solution for the vision-impaired. Every new Mac comes with Mac OS X and VoiceOver installed and includes a variety of accessible More than 50 reasons to use applications. You can also purchase additional Apple and third-party applications to use with VoiceOver. VoiceOver. Learn more While this page lists a few of the most popular applications, many more are available. If you use an application with VoiceOver that’s not on this list, and you would like to have it added, send email to [email protected]. Unlike traditional screen readers, VoiceOver is integrated into the operating system, so you can start using new accessible applications right away. You don’t need to buy an update to VoiceOver, install a new copy, or add the application to a “white list.” Moreover, VoiceOver commands work the same way in every application, so once you learn how to use them, you’ll be able to apply what you know to any accessible application. Apple provides developers with a Cocoa framework that contains common, reusable application components (such as menus, text fields, buttons, and sliders), so developers don’t have to re-create these elements each time they write a new application. -

Imail V12 Web Client Help

Ipswitch, Inc. Web: www.imailserver.com 753 Broad Street Phone: 706-312-3535 Suite 200 Fax: 706-868-8655 Augusta, GA 30901-5518 Copyrights ©2011 Ipswitch, Inc. All rights reserved. IMail Server – Web Client Help This manual, as well as the software described in it, is furnished under license and may be used or copied only in accordance with the terms of such license. Except as permitted by such license, no part of this publication may be reproduced, photocopied, stored on a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording, or otherwise, without the expressed prior written consent of Ipswitch, Inc. The content of this manual is furnished for informational use only, is subject to change without notice, and should not be construed as a commitment by Ipswitch, Inc. While every effort has been made to assure the accuracy of the information contained herein, Ipswitch, Inc. assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions. Ipswitch, Inc. also assumes no liability for damages resulting from the use of the information contained in this document. Ipswitch Collaboration Suite (ICS), the Ipswitch Collaboration Suite (ICS) logo, IMail, the IMail logo, WhatsUp, the WhatsUp logo, WS_FTP, the WS_FTP logos, Ipswitch Instant Messaging (IM), the Ipswitch Instant Messaging (IM) logo, Ipswitch, and the Ipswitch logo are trademarks of Ipswitch, Inc. Other products and their brands or company names are or may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are the property of their respective companies. Update History December 2011 v12 April 2011 v11.5 October 2010 v11.03 May 2010 v11.02 Contents CHAPTER 1 Introduction to IMail Web Client About Ipswitch Web Messaging Help ..................................................................................................................