Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open As a Single Document

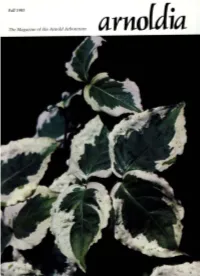

Vol. 43 No. 4 Fall 1983 arno ·~a Amoldia (ISSN 0004-2633) is published quarterly in Page spnng, summer, fall, and winter by the Arnold 3 Cultivars of Japanese Plants at Arboretum of Harvard University. Brookside Gardens Carl R. Hahn and R. Subscriptions are $10.00 per year, single copies $3.00. Barry Yinger Second-class postage paid at Boston, Massachusetts. 20 Of Birds and Bayberries: Seed Dispersal Postmaster: Send address changes to: and Propagation of Three Myrica Arnoldia Species Fordham The Arnold Arboretum Alfred J. The Arborway 24 H. Jamaica Plain, MA 02130 E. Wilson, Yichang, and the Kiwifruit Copynght © 1983 President and Fellows of Harvard College 23 BOOKS Etleen J Dunne, Editor Peter Del Tredici, Associate Editor Front cover photo Leaves of Cornus kousa ’Snowboy’, a vanegated dogwood cultivar recently mtroduced from Japan by Brookside Gardens, Wheaton, Maryland. Carl R Hahn, photo Back cover photo~ Fruit of the common bayberry (Mynca pensylvamca~. A1 Bussemtz, photo. Cultivars of Japanese Barry R. Yinger and Carl R. Hahn Plants at Brookside Gardens Since 1977 Brookside Gardens, a publicly some were ordered from commercial supported botanical garden within the nurseries. Montgomery County, Maryland, park sys- has maintained a collections tem, special Cultivar Names of Japanese Plants program to introduce into cultivation orna- mental plants (primarily woody) not in gen- One of the persistent problems with the eral cultivation in this country. Plants that collections has been the accurate naming of appear to be well-suited for the area are Japanese cultivars. In our efforts to assign grown at the county’s Pope Farm Nursery in cultivar names that are in agreement with sufficient quantity for planting in public both the rules and recommendations of the areas, and others intended for wider cultiva- International Code of Nomenclature for tion are tested and evaluated in cooperation Cultivated Plants, 1980, we encountered with nurseries and public gardens through- several problems. -

UNSH Newsletter June 2020.6

UNSH Newsletter Edition 2020.6. JUNE The World Federation Rose Convention in Adelaide that was to be held in 2021, has been postponed to 27th October - 3rd November 2022. The National Rose Show in Kiama that was to be held in October 2020 has now been postponed to 2021. The Nepean, Sydney & Macarthur Rose Shows that were to be held in October 2020 have all been cancelled. The Rose Society of NSW: Upper North Shore & Hills Regional Email: unsh. [email protected] Phone: 9653 2202 (9am - 7 pm) Facebook: UNSH Rose Regional UNSH meets on 3rd Sunday of each month in 2020. Meeting time: 2 pm Autumn/Winter;4 pm Spring/Summer PLEASE ARRIVE 15 minutes earlier to ‘Sign On’; buy raffle tickets Patron: Sandra Ross UNSH Rose Advisors: Brigitte & Klaus Eckart Chair & Editor: Kate Stanley Assistant Chair: David Smith UNSH Signature Roses: Sombreuil & Kardinal Treasurer: Judy Satchell Secretary: Paul Stanley Table of Contents… What’s happening at UNSH?......page 2 Creative with Climbers…..page 3 Pegging Roses….page 4 UNSH survey:What Is the olderst rose that you have planted in your garden?...page 5 Nursery Roundup-a quick reference….page 6 News clipping on Darling Nursery and John Baptiste’s Garden…page 7 Nurseries in Colonial Times…page 7 • Shepherd’s Darling Nursery (c.1827) • John Baptiste’s Nursery (1832)…page 8 • Camden Park Nursery (1844)…page 9 • Guilfoyle’s Exotic Nursery (1851)…page 10,11 Timeline- Guilfloyle…page 12 Wardian Case…page 13 Cover Guilfoyle Cat 1866…page 14 Timeline Nurseries…pages 15,16 Legacy of Guilfoyle & evidence of hybridisation…page 17 Annotated 1866 Guilfoyle Catalogue…pages 18-38 (Key : 18) Final thoughts..page 39 • Hazelwood Nursery (1908)… page 40 Bibliography…pages 40,41 UNSH June Newsletter Page 1 What’s happening at UNSH? Membership Renewal due by June 30th 2020. -

Nepenthes Argentii Philippines, N. Aristo

BLUMEA 42 (1997) 1-106 A skeletal revision of Nepenthes (Nepenthaceae) Matthew Jebb & Martin Chee k Summary A skeletal world revision of the genus is presented to accompany a family account forFlora Malesi- ana. 82 species are recognised, of which 74 occur in the Malesiana region. Six species are described is raised from and five restored from as new, one species infraspecific status, species are synonymy. Many names are typified for the first time. Three widespread, or locally abundant hybrids are also included. Full descriptions are given for new (6) or recircumscribed (7) species, and emended descrip- Critical for all the Little tions of species are given where necessary (9). notes are given species. known and excluded species are discussed. An index to all published species names and an index of exsiccatae is given. Introduction Macfarlane A world revision of Nepenthes was last undertaken by (1908), and a re- Malesiana the gional revision forthe Flora area (excluding Philippines) was completed of this is to a skeletal revision, cover- by Danser (1928). The purpose paper provide issues which would be in the ing relating to Nepenthes taxonomy inappropriate text of Flora Malesiana.For the majority of species, only the original citation and that in Danser (1928) and laterpublications is given, since Danser's (1928) work provides a thorough and accurate reference to all earlier literature. 74 species are recognised in the region, and three naturally occurring hybrids are also covered for the Flora account. The hybrids N. x hookeriana Lindl. and N. x tri- chocarpa Miq. are found in Sumatra, Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo, although rare within populations, their widespread distribution necessitates their inclusion in the and other and with the of Flora. -

Botanical Explorers

BOTANICAL EXPLORERS PEOPLE, PLACES & PLANT NAMES HOW it all began PRIOR TO 1450 ´ ROMAN EMPIRE extended around entire Mediterranean Sea ´ Provided overland trade route to the east ´ Fall of Constantinople to Ottoman Turks in 1453, impeding overland travel THE AGE OF DISCOVERY 1450-1750 Europeans continued to trade through Constantinople into 16th century High prices, bandits, tolls, taxes propelled search for sea routes EASTERN COMMODITIES Tea, spices, silks, silver, porcelain ´ Still life with peaches and a ´ Offering pepper to the king lemon, 1636 (Chinese ´ from Livre des Merveilles du Monde, 15th c porcelain), Jurian van Streek Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris THE AGE OF DISCOVERY Europe Portuguese/Spanish pioneer new trade routes to the Indies by sea Commercial expeditions sponsored by European monarchies First voyages sailed south around tip of Africa and then east toward India THE AGE OF DISCOVERY America ´1492-1502 Columbus and others believed they would reach Asia by sailing west ´Discovery of the ”New World” AGE OF DISCOVERY Japan Japan had no incentive to explore; Wealthy trade partners, China and Korea AGE OF DISCOVERY Japan ´1543 1st Portuguese ship arrives ´Daimyo (feudal lord) allows Portuguese into Japanese ports to promote trade and Christianity ´Portuguese trade ships sail from home port of Indian colony, Goa, to Japan other Far East ports, returning to Goa after 3- year journeys AGE OF DISCOVERY China Treasure ships under command of Zheng He (in white) Hongnian Zhang, oil painting of China’s naval hero Inland threats led -

Penang Story

Deakin Research Online This is the published version: Jones, David 2010, Garden & landscape heritage:a crisis of tangible & intangible comprehension and curatorship, in ASAA 2010 : Proceedings of the 18th Asian Studies Association of Australia Biennial Conference of the ASAA : Crises and Opportunities : Past, Present and Future, Asian Studies Association of Australia, [Adelaide, S.A.], pp. 1-23. Available from Deakin Research Online: http://hdl.handle.net/10536/DRO/DU:30033304 Every reasonable effort has been made to ensure that permission has been obtained for items included in Deakin Research Online. If you believe that your rights have been infringed by this repository, please contact [email protected] Copyright : 2010, Asian Studies Association of Australia Asian Studies Association of Australia : 18th Biennial Conference 2010 Garden & Landscape Heritage: A Crisis of Tangible & Intangible Comprehension and Curatorship1 Dr David Jones School of Architecture & Building, Deakin University Email [email protected] ABSTRACT The cultural landscape of George Town, Penang, Malaysia, embraces the historic enclave of George Town as well as a range of other significant colonial vestiges adjacent to the entrépôt. Many of these landscapes cannot be isolated from the énclave as they are integral to and part of its cultural mosaic and character. Perhaps the most important are the Penang Hill hill-station landscape and the ‗Waterfall‘ Botanic Gardens. The latter is an under-valued ‗garden of the empire‘—a garden that significantly underpinned the development and historical and botanical stature of the Singapore Botanic Gardens. This paper reviews the cultural significance of colonial botanic gardens as they were established around the world during the scientific explosion of the late 1800s. -

FEATURES Geophysical Surveying by Cook and Flinders Knowledge

AUGUST 2017 • ISSUE 189 ABN 71 000 876 040 ISSN 1443-2471 Australian Society of Exploration Geophysicists PREVIEW NEWS AND COMMENTARY FEATURES Trump’s cuts to science: how they aff ect us Geophysical surveying by Cook and Flinders Clean energy: good news for minerals Miniaturisation technology Knowledge about exploration geophysical Interpretation formulae methods in Australia prior to the Phishing for beginners IGES (1928–1930) The C Suite 6XEVXUIDFH([SORUDWLRQ7HFKQRORJLHV ŝŶƉĂƌƚŶĞƌƐŚŝƉǁŝƚŚ 5HVRXUFH3RWHQWLDOVDUHJHRSK\VLFDOFRQVXOWDQWVVSHFLDOLVLQJLQDUDQJHRIJHRSK\VLFDOPHWKRGV VXUYH\GHVLJQEXGJHWLQJDFTXLVLWLRQDQG4$4&GDWDSURFHVVLQJPRGHOOLQJDQGLQYHUVLRQGDWD LQWHJUDWLRQDQGLQWHUSUHWDWLRQRIJHRSK\VLFDOUHVXOWV 6DOHVUHQWDOVVXUYH\LQJDQGGDWDSURFHVVLQJIRUHTXLSPHQWGHYHORSHGE\0R+RVUO ,WDO\ 3OHDVHFRQWDFW5HVRXUFH3RWHQWLDOVIRUIXUWKHULQIRUPDWLRQ 3DVVLYHDQGDFWLYHVHLVPRPHWHU 6HOIFRQWDLQHGZLWKLQEXLOW$'GDWDUHFRUGHUDQG PHPRU\*36UDGLRWULJJHURUV\QFKURQLVDWLRQSRZHUHG E\LQEXLOWUHFKDUJHDEOHEDWWHULHVYLD86%WRSRZHUSOXJ DGDSWHURU3& 6PDOODQGOLJKWKLJKSUHFLVLRQWULD[LDOYHORFLPHWHUV +] N+]UDQJH DQGDFFHOHURPHWHUV 3DVVLYHVHLVPLF VWUDWLJUDSK\DQGGHSWKWRIUHVKURFN VRXQGLQJV VHLVPLFDPSOLILFDWLRQDQDO\VLVDQG0$6:IRU VLWHFKDUDFWHULVDWLRQ 9LEUDWLRQPRQLWRULQJDQGPRGHODQDO\VLVRIVWUXFWXUHV 86%GRZQORDGRULQWHUIDFHIRUFRQWLQXRXVPRQLWRULQJRU OLQNHGDUUD\V &RPHVZLWK*ULOODSURFHVVLQJDQGPRGHOOLQJVRIWZDUH 6HOIFRQWDLQHGGLJLWDOPXOWLFKDQQHOVHLVPLFIRU'' 6HOIFRQWDLQHGQHWZRUNHGPXOWLFKDQQHO SDVVLYHVHLVPLFDQGDOOFRQYHQWLRQDODFWLYHDQG UHVLVWLYLW\VXUYH\LQJDQG(57 SDVVLYHVHLVPLF 0$6:5(0,UHIUDFWLRQUHIOHFWLRQ /LJKWZHLJKW$'FRQYHUVLRQDWFDEOH -

Linnean Vol 31 1 April 2015 Press File.Indd

TheNEWSLETTER AND PROCEEDI LinneanNGS OF THE LINNEAN SOCIETY OF LONDON Volume 31 Number 1 April 2015 Harbingers: Orchids: The Ternate Essay: Darwin’s evolutionary A botanical and Revisiting the timeline forefathers surgical liaison and more… A forum for natural history The Linnean Society of London Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BF UK Toynbee House, 92–94 Toynbee Road, Wimbledon SW20 8SL UK (by appointment only) +44 (0)20 7434 4479 www.linnean.org [email protected] @LinneanSociety President SECRETARIES COUNCIL Prof Dianne Edwards CBE FRS Scienti fi c The Offi cers () Prof Simon Hiscock Vice Presidents President-Elect Dr Francis Brearley Prof Paul Brakefi eld Dr Malcolm Scoble Prof Anthony K Campbell Vice Presidents Editorial Dr Janet Cubey Ms Laura D'Arcy Prof Paul Brakefi eld Prof Mark Chase FRS Prof Jeff rey Duckett Prof Mark Chase Dr Pat Morris Dr John David Collecti ons Dr Thomas Richards Dr Anjali Goswami Dr John David Prof Mark Seaward Prof Max Telford Treasurer Strategy Dr Michael R Wilson Prof Gren Ll Lucas OBE Prof David Cutler Dr Sarah Whild Ms Debbie Wright THE TEAM Executi ve Secretary Librarian Conservator Dr Elizabeth Rollinson Mrs Lynda Brooks Ms Janet Ashdown Financial Controller & Deputy Librarian Digiti sati on Project Offi cer Membership Offi cer Mrs Elaine Charwat Ms Andrea Deneau Mr Priya Nithianandan Archivist Emerita Linnaean Project Conservators Buildings & Offi ce Manager Ms Gina Douglas Ms Helen Cowdy Ms Victoria Smith Ms Naomi Mitamura Special Publicati ons Manager Communicati ons & Events Ms Leonie Berwick Manager Mr Tom Simpson Manuscripts Specialist Dr Isabelle Charmanti er Room Hire & Membership Educati on Offi cer Assistant Mr Tom Helps Ms Hazel Leeper Editor Publishing in The Linnean Ms Gina Douglas The Linnean is published twice a year, in April and October. -

Front Index/Section

246 Combined Proceedings International Plant Propagators’ Society, Volume 52, 2002 The Role of the Veitch Nursery of Exeter in 19th Century Plant Introductions 247 Among interesting perennials are the luxuriant Myosotidium hortensia, the Chatham Island forget-me-not; blue poppies such as Meconopsis betonicifolia, M. grandis and the hybrid ‘Lingholm’; and many members of the Iridaceae such as Dietes, Diplarrhena, Libertia, Orthrosanthus, and Watsonia. The very distinctive Arisaema do well here, as do an increasing number of plants in the Convallaria- ceae, including Disporum, Polygonatum, Smilacina, Tricyrtis, and Uvularia. PLANTING CONDITIONS The windy conditions discourage the planting of large specimens, though the shallow soil in some places makes this physically impossible, while the severe infes- tation of honey fungus, Armillaria sp., precludes the direct transplanting of woody plants, which eventually fall victim to the fungus. Lifted rhododendrons are potted into very wide, shallow containers for a year or two before being surface planted, a method which has become the rule without cultivated beds, by simply placing the rootball on the soil and mounding up with the chosen medium. This seems to encourage establishment and may slow the invading Armillaria. Where rhododen- drons are planted on mossy rocks or stumps, particular care has to be taken during dry periods as the lack of mains water or any distribution system makes watering practically impossible and establishment unlikely. The Role of the Veitch Nursery of Exeter in 19th Century Plant Introductions© Mike Squires 1 Feeber Cottage, Westwood, Broadclyst, Exeter, EX5 3DQ The story of the Veitch family of Exeter is more than the story of the British love of plants. -

The Vanda Miss Joaquim Story Courtesy of the Singapore Botanic Gardens Herbarium

BIBLIOASIA APR – JUN 2018 Vol. 14 / Issue 01 / Feature 2 Nadia Wright, a historian, Linda Locke, a Joaquim. Intrigued as to why Ridley’s In an 1894 paper delivered to the great grand-niece of Agnes Joaquim, and account had been replaced by a tale prestigious Linnean Society in England, Harold Johnson, an orchid enthusiast, of chance discovery in various stories Ridley reiterated that Vanda Hookeriana collaborated in this historiography of about the flower in Singapore, Wright had been “successfully crossed” with V. Singapore’s national flower, theVanda Miss decided to investigate. teres, Lindl., “producing a remarkably Joaquim. Locke is a former advertising CEO handsome offspring, V. x Miss Joaquim.” and the co-author of the recently released children’s book: Agnes and her Amazing This paper was published unaltered in The Birth of a Bloom 4 Orchid. Johnson and Wright’s second 1896. Ridley, who lived to be 100 years edition of Vanda Miss Joaquim: Singapore’s In 1893, Agnes Joaquim, or possibly her old, never wavered in his statement. National Flower & the Legacy of Agnes & brother Joe (Joaquim P. Joaquim), showed When Isaac Henry Burkill (Ridley’s suc- Ridley will be published in late 2018. Locke Henry Ridley a new orchid. After carefully cessor at the Botanic Gardens) checked and Johnson are Singaporeans, while examining the bloom, having it sketched, all of Ridley’s herbarium specimens Wright is an Australian. and preserving a specimen in the her- and redid the labels, he saw no reason barium of the Botanic Gardens, Ridley to dispute Ridley and recorded Joaquim sent an account of the orchid’s origin and as the creator. -

The Royal Horticultural Society's Lindley Library: Safeguarding Britain's Horticultural Heritage Transcript

The Royal Horticultural Society's Lindley Library: Safeguarding Britain's Horticultural Heritage Transcript Date: Wednesday, 22 May 2013 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 22 May 2013 The Royal Horticultural Society’s Lindley Library: Safeguarding Britain’s Horticultural Heritage Dr Brent Elliott The Royal Horticultural Society is the world’s largest horticultural society – membership passed the 400,000 mark this year – and it also has the world’s largest horticultural library. This would be the case even if we took only the principal branch, at the Society’s offices in London, into consideration; but there is also a major collection at the Society’s principal garden at Wisley, and smaller collections at its three other gardens. In 2011 the Lindley Library was given Designated status by the Museums and Libraries Association as a collection of national and international importance. 1. History Before I talk about the Library’s collections, I must give a brief history of the Society and its Library. The Society was originally known as the Horticultural Society of London; it was founded in 1804 by John Wedgwood and Sir Joseph Banks, and for its first two decades its primary purpose was to provide a forum where Fellows could read papers, the best of which were published in its Transactions, and display and comment on items of interest. By 1830, it had a garden at Chiswick, with a celebrated collection of fruit varieties; it was running a training programme for gardeners, among the graduates of which were Joseph Paxton, later to be knighted for his role in creating the Crystal Palace; and it was sending plant collectors to nearly every continent, and introducing many new plants into cultivation in Britain. -

Hortus Veitchii, a History of the Rise and Progress of the Nurseries of Messrs

Title: Hortus Veitchii, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Nurseries of Messrs. James Veitch and Sons, Together with an Account of The Botanical Collectors and Hybridists Employed by Them and a List of The Most Remarkable of Their Introductions. HORTUS VEITCHII Author: James H. Veitch. by Description: Hortus Veitchii was originally published by the famous nursery firm of James Veitch & Sons, Chelsea, London in 1906 to commemorate the huge JAMES H. VEITCH contribution made by this firm to western gardens in the introduction of new plants from around the world. This book is a study of the history of the botanical plant collecting explorers and hybridists, working for the nurseries of James Veitch and Son, Exeter and James Veitch and Sons, Chelsea during the period of 1840-1906. This includes chapters on the following; Lives of Travellers, Lives of Hybridists, Orchid Species, Orchid Hybrids, Stove and Greenhouse Plants, Insectivorous Plants, Exotic Ferns, Coniferous Trees, Trees and Shrubs and Climbing Plants, Herbaceous Plants, Bulbous Plants, Begonias, Hippeastrums, Orchid Hybridization, Nepenthes, Greenhouse Rhododendrons, Streptocarpus, Fruits and Vegetables. About the author: James Herbert Veitch F.L.S., F.R.H.S. was born in 1869 into a family of successful nurserymen. He was the eldest son of John Gould Veitch and like his father was to become a botanist and plant collector for the family nursery firm of James Veitch and Sons, Chelsea. Following a tour to the Far East and Australasia during 1891-1893 he wrote A Traveller’s Notes which was published by James Veitch and Sons in 1896. -

Ptychosperma Macarthurii : 85 Discovery, Horticulture and Obituary 97 Taxonomy Advertisements 84, 102 J.L

Palms Journal of the International Palm Society Vol. 51(2) Jun. 2007 THE INTERNATIONAL PALM SOCIETY, INC. The International Palm Society Palms (formerly PRINCIPES) NEW • UPDATED • EXPANDED Journal of The International Palm Society Founder: Dent Smith Betrock’sLANDSCAPEPALMS An illustrated, peer-reviewed quarterly devoted to The International Palm Society is a nonprofit corporation information about palms and published in March, Scientific information and color photographs for 126 landscape palms engaged in the study of palms. The society is inter- June, September and December by The International national in scope with worldwide membership, and the Palm Society, 810 East 10th St., P.O. Box 1897, This book is a revised and expanded version of formation of regional or local chapters affiliated with the Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897, USA. international society is encouraged. Please address all Betrock’sGUIDE TOLANDSCAPEPALMS inquiries regarding membership or information about Editors: John Dransfield, Herbarium, Royal Botanic the society to The International Palm Society Inc., P.O. Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AE, United Box 1897, Lawrence, Kansas 66044-8897, USA. e-mail Kingdom, e-mail [email protected], tel. 44- [email protected], fax 785-843-1274. 20-8332-5225, Fax 44-20-8332-5278. Scott Zona, Fairchild Tropical Garden, 11935 Old OFFICERS: Cutler Road, Coral Gables, Miami, Florida 33156, President: Paul Craft, 16745 West Epson Drive, USA, e-mail [email protected], tel. 1-305- Loxahatchee, Florida 33470 USA, e-mail 667-1651 ext. 3419, Fax 1-305-665-8032. [email protected], tel. 1-561-514-1837. Associate Editor: Natalie Uhl, 228 Plant Science, Vice-Presidents: Bo-Göran Lundkvist, PO Box 2071, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York 14853, USA, e- Pahoa, Hawaii 96778 USA, e-mail mail [email protected], tel.