Which Way Goes Romanian Capitalism? Making a Case for Reforms, Inclusive Institutions and a Better Functioning European Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Country Report Romania 2020

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 26.2.2020 SWD(2020) 522 final COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT Country Report Romania 2020 Accompanying the document COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN CENTRAL BANK AND THE EUROGROUP 2020 European Semester: Assessment of progress on structural reforms, prevention and correction of macroeconomic imbalances, and results of in-depth reviews under Regulation (EU) No 1176/2011 {COM(2020) 150 final} EN EN CONTENTS Executive summary 4 1. Economic situation and outlook 9 2. Progress with country-specific recommendations 17 3. Summary of the main findings from the MIP in-depth review 21 4. Reform priorities 25 4.1. Public finances and taxation 25 4.2. Financial sector 30 4.3. Labour market, education and social policies 33 4.4. Competitiveness, reforms and investment 45 4.5. Environmental Sustainability 63 Annex A: Overview Table 67 Annex B: Commission debt sustainability analysis and fiscal risks 75 Annex C: Standard Tables 76 Annex D: Investment guidance on Just Transition Fund 2021-2027 for Romania 82 Annex E: Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 85 References 90 LIST OF TABLES Table 1.1: Key economic and financial indicators 16 Table 2.1: Assessment of 2019 CSR implementation 19 Table 3.1: MIP assessment matrix (*) - Romania 2020 23 Table C.1: Financial market indicators 76 Table C.2: Headline Social Scoreboard indicators 77 Table C.3: Labour market and education indicators 78 Table C.4: Social inclusion and health -

Romanian Financial Highlights EN December

NEWS Romanian Financial Highlights – December 2012 Currency quotations Foreign exchange rates BNR base interest December 31, 2012 Quotation Date RON/EUR RON/USD Date Inflation rate % rate EUR/USD 1,32 21.dec 4,4451 3,3636 oct.12 0,29 Oct 5.25% USD/JPY 0,86 24.dec 4,4231 3,3468 nov.12 0,04 Nov 5.25% GBP/USD 1,62 27.dec 4,4296 3,3384 dec.12 0,60 Dec 5.25% USD/CHF 0,92 28.dec 4,4291 3,3619 2011 5,79 EUR/CHF 1,21 31.dec 4,4287 3,3575 2012 4,95 Source: National Bank of Romania, National Institute of Statistics RON/USD Evolution of National Currency (2010-2012) Evolution of national Currency (last month) - RON/EUR Evolution of national Currency (last month) - RON/USD RON/EUR 4,7 4,6800 3,5500 4,6400 4,2 3,4800 4,6000 4,5600 3,4100 3,7 4,5200 3,3400 4,4800 3,2 3,2700 4,4400 4,4000 3,2000 2,7 c c c c c c c 1 2 2 ec ec ec ec ec ec e e ec ec ec ec ec ec ec ec -10 11 -11 -11 -1 -11 12 -12 12 -12 -12 -1 12 D D D D D D D D D D D D D D D b-11 r- n ct b-12 n g-1 p ct v- -De -D -De - -De ec Jan-11 e pr Ju Jul-11 Jan- e pr ay- Ju Jul-12 u e 1-Dec 3- 5-Dec 7-Dec 9-Dec 9-De 1- 3 5- 7- 9-Dec 9-De D F Ma A May-11 Aug-11 Sep-11 O Nov Dec-11 F Mar-12 A M A S O No Dec-12 11- 13- 15 17- 1 21 23-Dec 25 27-Dec 29- 31-Dec 11-Dec 13-Dec 15- 17-Dec 19- 21- 23- 25- 27- 2 31 Deposits interest Futures quotations BMFMS 1) Futures quotations BMFMS Maturity Interest Interest Contract Maturity Amount Contract Maturity Amount ROBID ROBOR RON RON 1 month 5,54% 6,04% EUR/RON mar.13 4,5050 DESNP mar.13 0,4315 3 months 5,55% 6,05% EUR/RON iun.13 4,5500 DETLV mar.13 0,8715 6 months -

The Policy of the Exchange Rate Promoted by National Bank of Romania and Its Implications Upon the Financial Stability

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics THE POLICY OF THE EXCHANGE RATE PROMOTED BY NATIONAL BANK OF ROMANIA AND ITS IMPLICATIONS UPON THE FINANCIAL STABILITY Vechiu Camelia “Constantin Brâncoveanu” University Pite 2ti, Faculty of Management-Marketing in Economic Affairs, Br ;ila Enache Elena “Constantin Brâncoveanu” University Pite 2ti, Faculty of Management-Marketing in Economic Affairs, Br ;ila Marin Carmen “Constantin Brâncoveanu” University Pite 2ti, Faculty of Management-Marketing in Economic Affairs, Br ;ila Chifane Cristina “Constantin Brâncoveanu” University Pite 2ti, Faculty of Management-Marketing in Economic Affairs, Br ;ila The more profound world economic crisis has strongly marked the evolution of the Romanian financial system. The size of current account deficit, the relatively high external financing needs and the dependence of the banks on it, the high ratio between loans in foreign currency and deposits in foreign currency made of the Romanian economy, a risky destination for investors. In these conditions, since the end of 2008 and throughout 2009, the government's economic program was focused on reducing the external deficit in both public and private sector, on minimizing the effects of recession, on avoiding a crisis of the exchange rate and on cooling the inflationary pressures. Keywords: monetary policy, exchange rate, external financing, budget deficit JEL classification: E58 1. The interventions of NBR on the foreign exchange market Supported by the global financial crisis, the evolution of the Leu rate has raised major problems. As in the period 2005-2007, the currency incomings have overestimated the Romanian national currency way above the level indicated by the fundamental factors of the exchange rate, the reduction of the foreign financing and the incertitude have afterwards determined an unjustified depreciation of the Romanian Leu. -

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / ROMANIA

Timeline / 1870 to After 1930 / ROMANIA Date Country Theme 1871 Romania Rediscovering The Past Alexandru Odobescu sends an archaeological questionnaire to teachers all over the country, who have to return information about archaeological discoveries or vestiges of antique monuments existing in the areas where they live or work. 1873 Romania International Exhibitions Two Romanians are members of the international jury of the Vienna International Exposition: agronomist and economist P.S. Aurelian and doctor Carol Davila. 1873 Romania Travelling The first tourism organisation from Romania, called the Alpine Association of Transylvania, is founded in Bra#ov. 1874 Romania Rediscovering The Past 18 April: decree for the founding of the Commission of Public Monuments to record the public monuments on Romanian territory and to ensure their conservation. 1874 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Issue of the first sanitation law in the United Principalities. The sanitation system is organised hierarchically and a Superior Medical Council, with a consultative role, is created. 1875 - 1893 Romania Political Context Creation of the first Romanian political parties: the Liberal Party (1875), the Conservative Party (1880), the Radical-Democratic Party (1888), and the Social- Democratic Party of Romanian Labourers (1893). 1876 Romania Reforms And Social Changes Foundation of the Romanian Red Cross. 1876 Romania Fine And Applied Arts 19 February: birth of the great Romanian sculptor Constantin Brâncu#i, author of sculptures such as Mademoiselle Pogany, The Kiss, Bird in Space, and The Endless Column. His works are today exhibited in museums in France, the USA and Romania. 1877 - 1881 Romania Political Context After Parliament declares Romania’s independence (May 1877), Romania participates alongside Russia in the Russian-Ottoman war. -

Politics of Balance

CENTRE INTERNATIONAL DE FORMATION EUROPEENNE INSTITUT EUROPEEN DES HAUTES ETUDES INTERNATIONALES Academic Year 2005 – 2006 Politics of Balance The Conjuncture of Ethnic Party Formation and Development in Romania and Bulgaria Lilla Balázs M.A. Thesis in Advanced European and International Studies Academic Supervisor MATTHIAS WAECHTER Director of the DHEEI Nice, June 2006 1 Contents 1. Introduction 2. The Emergence of the Two Ethnic Parties 2.1. The Birth of New Nation States 2.2. Romania: Revolution and the “Morning After” 2.2.1. Timisoara and the Fall of Ceausescu 2.2.2. The “Morning After” and Formation of the DAHR 2.3. Bulgaria: Revolution and the “Morning After” 2.3.1. The Fall of Zhivkov 2.3.2. The “Morning After” and Formation of the MRF 3. Politics of Balance: the Two Parties at a Closer Look 3.1. The DAHR and the MRF: Two Ethnic Parties in Context 3.1.1. Ethnic Parties 3.1.2. The Context of Minority Ethnic Parties 3.2. The DAHR and its Context 3.2.1. The DAHR—Ethnic Organization in National Politics 3.2.2. The DAHR in Context 3.3. The MRF and its Context 2 3.3.1. The MRF—Ethnic Party of a National Type 3.3.2. The MRF in Context 3.4. Ethnic Party Politics: Politics of Balance 4. The Dynamic of Ethnic Party Politics in Romania and Bulgaria 4.1. The DAHR and Political Developments in Romania 4.1.1. Radicalism and Isolation: 1992-1996 4.1.2. Electoral Revolution and Participation: 1996-2000 4.1.3. -

60 Years of Radio Free Europe in Munich and Prague

VOICES OF FREEDOM – WESTERN INTERFERENCE? 60 YEARS OF RADIO FREE EUROPE IN MUNICH AND PRAGUE Radio Free Europe (RFE) began regular broadcasts from Munich sixty years ago with a news programme by its Czechoslovak department. To mark this anniversary, the Collegium Carolinum (Munich), together with the Czech Centre (Munich), and the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes (Prague) held the conference Voices of Freedom – Western Interference? 60 Years of Radio Free Europe in Munich and Prague from 28 to 30 April 2011 at Munich’s Ludwig-Maximilian University. The conference revolved around RFE’s role as one of the most political and polarizing of all international radio broadcasters in the Cold War context. What were the station’s goals and how did it go about achieving them? To what extent did RFE contribute to an exchange of information and knowledge between East and West? The station’s political significance and the importance attached to similar international media in current politics and foreign affairs were demonstrated not least by the fact that the conference was held under the auspices of the Bavarian Prime Minister Horst Seehofer and the Czech Foreign Minister Karel Schwarzenberg. This was also clear in the public discussion on the theme of “International Broadcasting Today” at America House with former RFE journalist and current President of Estonia Toomas Hendrik Ilves, US Consul General Conrad R. Tribble, political scientist and media expert Hans J. Kleinsteuber (University of Hamburg), Associate Director of Broadcasting at RFE/RL in Prague, Abbas Djavadi, and Ingo Mannteufel from the Deutsche Welle. In the introductions and contributions of this discussion the tensions between political regard for the station, scholarly insights, and the perspectives of contemporary witnesses that were felt throughout the conference were already apparent. -

Mugur Isărescu

Mugur Isărescu: Is European financial integration stalling? Opening remarks by Mr Mugur Isărescu, Governor of the National Bank of Romania, at the EUROFI High Level Seminar, Bucharest, 3 April 2019. * * * Honourable guests, Ladies and gentlemen, Please allow me to welcome you here, at the Royal Palace. We are honoured to host here, in Bucharest, so many outstanding guests at such a landmark event. It is a perfect occasion to exchange views and liaise with representatives of public and banking authorities and of the financial industry across the European Union. During the talks over the past few days, and particularly on the occasion of the EUROFI High- level Seminar, I heard strong voices from the banking community which were rather pessimistic about the prospects of further banking and financial integration. We, at the Eastern frontier of the EU, are compelled to take a more positive outlook regarding the future of our continent. Speaking about the difficulties of the financial sector in Europe, it is important to point out the positive aspects and evolutions as well. Certainly, favourable developments have taken place all over Europe and we should acknowledge them and move forward with more confidence. Specifically, financial fragmentation has been mitigated as a result of broad-based non-standard policy measures taken by the ECB. Looking ahead, completing the Economic and Monetary Union, which involves risk-sharing tools and risk-reduction efforts, is the way forward to address financial fragmentation. In the case of Romania, I could say we have already taken important steps towards joining the banking union: no public funds were resorted to after the crisis outbreak to support the banking system and now its liquidity and solvency ratios are well above the prudential thresholds. -

Cultural Effects on Real Estate Market: an Explanation of Urbanization

CULTURAL EFFECTS ON REAL ESTATE MARKET: AN EXPLANATION OF URBANIZATION Ling Wang Project submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of the degree of Master in Business Administration Supervisor: Prof. Rui Alpalhão, ISCTE Business School, Departamento de Finanças Sep 2016 Cultural effects on real estate market: an explanation of urbanization Resumo Este estudo investiga a Teoria do homem no comportamento do consumidor e as dimensões culturais de Hofstede, proporcionando uma compreensão mais profunda das atitudes dos consumidores relativamente ao investimento no mercado imobiliário para explicar a urbanização atual em diferentes países. Depois da quebra do mercado imobiliário e do processo de investimento imobiliário, os indicadores são seleccionados a partir de Atividades Económicas, Mercado Imobiliário, Risco e Limitação e dos Factores Culturais para explicar o fenómeno da urbanização para alcançar o objetivo deste trabalho. Após a realização do Stepwise, o resultado mostra que há ligação entre eles. Juntamente com o desempenho imobiliário, representado pelo Índice de Rendas e Índice de direito de propriedade, o índice cultural, representado pelo Índice de Incerteza e Prevenção e pelo Índice da Indulgência, bem como outros dois factores da Teoria do Comportamento do Consumidor – a Teoria do Homem é estatisticamente significativa para a urbanização. Palavras-chave: Investimento imobiliário · Diferenças culturais · Urbanização. JEL Sistema de Classificação: R29, R30, Z10. I Cultural effects on real estate market: an explanation of urbanization Abstract This study investigates the Theory of Man in Consumer Behavior and Hofstede Cultural dimensions by providing deeper understanding of consumers‟ attitudes towards investment in real estate market to explain nowadays´ urbanization in different countries. After breaking down the Real estate market and RE investment process, the predictors are selected from Economic Activities, Real Estate Market, Risk and Limitation and Cultural Factors to explain the Urbanization phenomenon to reach the purpose of this paper. -

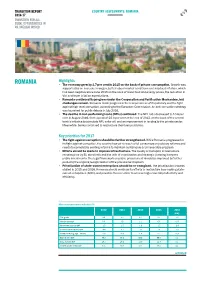

Romania 01 2016-17 Transition for All: Equal Opportunities in an Unequal World

TRANSITION REPORT COUNTRY ASSESSMENTS: ROMANIA 01 2016-17 TRANSITION FOR ALL: EQUAL OPPORTUNITIES IN AN UNEQUAL WORLD Highlights ROMANIA • The economy grew by 3.7 per cent in 2015 on the back of private consumption. Growth was supported by an increase in wages, better labour market conditions and subdued inflation, which has been negative since June 2015 on the back of lower food and energy prices, the reduction in VAT and lower inflation expectations. • Romania continued its progress under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism, but challenges remain. Romania made progress in the independence of its judiciary and the fight against high-level corruption, according to the European Commission. An anti-corruption strategy was launched for public debate in July 2016. • The decline in non-performing loans (NPLs) continued. The NPL ratio decreased to 10.6 per cent in August 2016, from a peak of 22.0 per cent at the end of 2013, on the back of the central bank’s initiative to stimulate NPL write-off, and an improvement in lending to the private sector. Meanwhile, banks continued to restructure their loan portfolios. Key priorities for 2017 • The fight against corruption should be further strengthened. While Romania progressed in its fight against corruption, the country has yet to reach a full consensus on judiciary reforms and needs to consolidate existing reforms to maintain sustainable and irreversible progress. • Efforts should be made to improve infrastructure. The quality of transport infrastructure remains poor by EU standards and the lack of coordination and strategic planning hampers public investments. The legal framework on public procurement should be improved by further pursuing the ongoing reorganisation of the procurement system. -

The National Bank of Romania Uses FT Content to Foster Its Agility and Adaptability Ft.Com/Group

The National Bank of Romania uses FT content to foster its agility and adaptability ft.com/group The challenge The solution The benefits The strategic decisions taken by the An FT Group Subscription provides Teams and senior colleagues across National Bank of Romania originate a common source of analysis that the National Bank of Romania are in trustworthy political and economic strategists and decision-makers can on the same page when it comes to insight on Europe and beyond. Up use to gain a big picture view of the their understanding of the global to date information is constantly world and identify key themes that financial and political outlook. required in order to adapt to the their specialised teams can then Major policy decisions are informed demanding new challenges facing a explore in greater depth. by accurate analysis and trusted modern central bank. intelligence. You have to go beyond your own box and your own culture. Reading the FT enriches your knowledge and makes us more skilful as an institution. Gabriela Mihailovici Strategy consultant, National Bank of Romania Supporting Romania’s Although the long-term aim is a return to a normal monetary stance, the ‘new normal’ is likely to be rather economic health different. It’s commonly acknowledged that the core objective of Teams across the NBR therefore need to ensure they the majority of central banks is to ensure and maintain have access to accurate sources of analysis in order to price stability. be agile in their strategic decision-making. The National Bank of Romania (NBR), headquartered in Bucharest, shares this primary goal with its EU/ESCB counterparts but equally, the role of central banks is A complicated, global game ever-growing in an environment marked by unusually elevated uncertainties. -

Post-Communist Romania

Political Science • Eastern Europe Carey Edited by Henry F. Carey Foreword by Norman Manea “Henry Carey’s collection captures with great precision the complex, contradic- tory reality of contemporary Romania. Bringing together Romanian, West European, and American authors from fields as diverse as anthropology, politi- Romania cal science, economics, law, print and broadcast journalism, social work, and lit- ROMANIA SINCE 1989 erature, the volume covers vast ground, but with striking detail and scholarship and a common core approach. Romania since 1989 provides perhaps the most comprehensive view of the continuing, murky, contested reality that is Romania today and is a must read for any scholar of modern Romania, of East-Central Europe, and of the uncertain, troubled, post-socialist era.” since 1989 —David A. Kideckel, Central Connecticut State University Sorin Antohi “The wealth of detail and quality of insights will make this an excellent source- Wally Bacon book for students of political change after the Cold War. It should be taken seri- Gabriel Ba˘ descu ously by policy practitioners increasingly involved with Romania’s problems.” Zoltan Barany —Tom Gallagher, Professor of Peace Studies, Bradford University, U.K. Politics, Jóhanna Kristín Birnir Larry S. Bush Those who study Romania must confront the theoretical challenges posed by a Economics, Pavel Câmpeanu country that is undergoing a profound transformation from a repressive totali- Henry F. Carey tarian regime to a hazy and as yet unrealized democratic government. The most and Society Daniel Da˘ ianu comprehensive survey of Romanian politics and society ever published abroad, Dennis Deletant this volume represents an effort to collect and analyze data on the complex prob- Christopher Eisterhold lems of Romania’s past and its transition into an uncertain future. -

Strategic Interactions Between NATO, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania After 2000

Strategic Interactions Between NATO, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria and Romania After 2000 A Report to the NATO Academic Forum for 1998-2000 By Laure Paquette, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Lakehead University Thunder Bay, Ontario Canada 30 June 2000 1 Executive Summary............................................................3 Chapter 1. Introduction.....................................................5 Chapter 2. Analysis of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization..............37 Chapter 3. The New Member: Poland.........................................50 Chapter 4. The New Member: the Czech Republic..............................66 Chapter 5. The Aspiring Member: Romania...................................82 Chapter 6. Bulgaria........................................................97 2 Executive Summary NATO is newly aware of its increased status as a force for stability in a drastically altered Atlantic community. The number of its initiatives is on the increase just as a new political, economic and military Europe emerges. The Cold War's end has wrought as many changes as there are continuities in the security environment. Eastern and central European states, especially NATO and PfP members, enjoy an increasing importance to NATO, both as trading partners and as new participants in the civil society. While the literature on relations between NATO and the East Europeans is rather limited, the study of the overall posture of those states in the international system is almost non-existent, so that the consequences of their posture for NATO’s renewed concept are unknown. The study of these countries' security posture and strategic interactions with Central European states in general promotes the renewed role of NATO. The study shows that the each of long-term relations with Poland, the Czech Republic, Romania and Bulgaria is subordinated to the goal of entering the European Union, and that their different values will makes relations difficult.