0306 Transnistria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnistrian Region December 2015

Regional Economic Review: Transnistrian Region December 2015 Disclaimer This document is published by the Independent Think-Tank Expert-Grup within the Program “Support to Confidence Building Measures”, financed by the EU Delegation in Moldova and implemented by United Nations Development Programme in Moldova. Opinions expressed in this document belong to the authors and are not necessarily the opinions of the donors. Also, the authors are aware of potential risks related to quality of the statistical data and have used the data with due precaution. This document is a translation from the Romanian language. 2 Regional Economic Review: Transnistrian Region December 2015 Contents List of figures .............................................................................................................................................. 3 List of tables ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Key messages of this issue....................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Domestic Supply ...................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2. Domestic Demand................................................................................................................. -

THE BENEFITS of ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia's

v53.i4.524.king 9/27/01 5:18 PM Page 524 THE BENEFITS OF ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States By CHARLES KING* AR is the engine of state building, but it is also good for busi- Wness. Historically, the three have often amounted to the same thing. The consolidation of national states in western Europe was in part a function of the interests of royal leaders in securing sufficient rev- enue for war making. In turn, costly military engagements were highly profitable enterprises for the suppliers of men, ships, and weaponry. The great affairs of statecraft, says Shakespeare’s Richard II as he seizes his uncle’s fortune to finance a war, “do ask some charge.” The distinc- tion between freebooter and founding father, privateer and president, has often been far murkier in fact than national mythmaking normally allows. Only recently, however, have these insights figured in discussions of contemporary ethnic conflict and civil war. Focused studies of the me- chanics of warfare, particularly in cases such as Sudan, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, have highlighted the complex economic incentives that can push violence forward, as well as the ways in which the easy labels that analysts use to identify such conflicts—as “ethnic” or “religious,” say—always cloud more than they clarify.1 Yet how precisely does the chaos of war become transformed into networks of profit, and how in turn can these informal networks harden into the institutions of states? Post-Soviet Eurasia provides an enlightening instance of these processes in train. In the 1990s a half dozen small wars raged across the region, a series of armed conflicts that future historians might term collectively the * The author would like to thank three anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft of this article and Lori Khatchadourian, Nelson Kasfir, Christianne Hardy Wohlforth, Chester Crocker, and Michael Brown for helpful conversations. -

The Extraterritorial Application of the European Convention on Human

! FACULTY OF LAW Lund University Lidia Carchilan The extraterritorial application of the European Convention on Human Rights and the United Nations Convention against Torture in frozen conflict regions as a tool of ensuring the prohibition of torture — the cases of Transnistria and Abkhazia JAMM07 Master Thesis International Human Rights Law 30 higher education credits Supervisor: Vladislava Stoyanova Term: Spring term 2019 !1 of !75 Table of contents Abstract …………………………………………………………………………….3 Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………….4 Abbreviations and acronyms…………………………………………………………5 Map no.1 of the Soviet Union and map no.2 of contemporary Abkhazia……………6 Map no.3 of contemporary Transnistria and map no.4 of contemporary Eastern Europe……………………………………………………………………….….……7 Chapter 1. Thesis outline and historical background……………………………8 1.1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………….8 1.2. Research questions, motivation of choice and limitations, previous research and contribution to scholarship………………………………………………….………10 1.3. Theory and methodology ………………………………………………………13 1.4. Historical background - Transnistria and Abkhazia……………………………14 Chapter 2. Jurisdiction and responsibility of States for activities perpetrated outside their territory…………………………………………………………….24 2.1. The notion of jurisdiction………………………………………………………24 2.2. International Court of Justice (ICJ) - attribution of conduct under the strict and effective control test………………………………………………………………27 2.3. International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) - attribution of conduct under the overall control test……………………………………………28 2.4. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) jurisdiction under the effective overall control test…………………………………………………………………29 Chapter 3. Legal considerations regarding extraterritoriality of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)…………………………………………31 3.1. General case-law that developed the extraterritorial nature of the ECHR……..33 3.2. Specific ECtHR case-law concerning the frozen conflict regions of Transnistria and Abkhazia………………………………………………………………………38 Chapter 4. -

Executive Summary Since Its Independence in 1991, Moldova, A

Executive Summary Since its independence in 1991, Moldova, a former Soviet republic, has made significant progress towards adopting the principles of a free market democracy. However, it has a mixed record of reforms over the years with past practices afflicting its public and private sectors and showcasing its institutional weaknesses. The political turmoil of 2013 highlighted the major shortcomings of its business environment and governmental practices despite a declared understanding of the need for more foreign direct investment. Controversies in the banking and financial sectors and questionable governmental decisions conceding control in several key sectors rocked the country. Despite slight progress reported by the latest World Bank Survey on Ease of Doing Business, recent efforts to tackle corruption, increase transparency in decision-making, cut bureaucracy, and uphold the rule of law have yet to make significant improvements in the investment climate. A new government was created in 2013, which continued the previous government’s path toward greater integration with the EU. The government initialed its Association Agreement (AA) with the EU, including a deep and comprehensive free trade agreement (DCFTA), in November 2013. With the signing of the AA expected to occur no later than early autumn of 2014, Moldova will be firmly set on a course of deeper reforms to bring its governmental, regulatory, and business practices in line with EU standards. The implementation of the DCFTA will integrate Moldova further into the EU market and create more opportunities for investment as a bridge between the vast markets of the EU and former Soviet republics. The business climate remains challenging. -

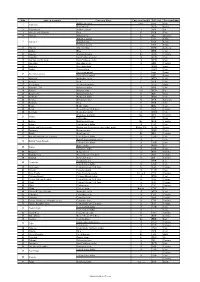

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Viktoria Potapkina

Nation Building in Contested States Viktoria Potapkina TESI DOCTORAL UPF/ANY 2018 DIRECTOR DE LA TESI Dr. Klaus-Jürgen Nagel DEPARTAMENT DE CIENCIES POLITIQUES I SOCIALS For My Family Acknowledgments I am grateful to UPF for being my academic “home” during the time I spent writing this thesis. I want to thank all the professors for their advice, critique and guidance. It was a long, but greatly enriching venture. My utmost gratitude goes to my supervisor, Dr. Klaus-Jürgen Nagel, who generously offered his time and expertise to discuss my work with me. I am thankful for his invaluable suggestions, endless encouragement, deliberation and guidance from day one. I would like to thank my friends and colleagues, who took the time to discuss my research with me, read various drafts and chapters, and generally supported me every step of the way. I am grateful to all the people who took their time to share their insight and observations with me in and about Northern Cyprus and Kosovo during the time I spent there. Finally, I would like to thank my family who have supported me during this uneasy process. My most sincere thanks go to my parents, grandparents and brother, who have provided me with unconditional support and encouragement. This thesis would not have been possible without their unfailing support. v vi Resum (Catalan) Aquesta tesi consisteix en una anàlisi dels processos de construcció nacional (nation-building) actuals. Centrada específicament en els casos de la República Turca del Nord de Xipre, la República Moldava de Pridnestroviana i Kosovo, es basa en dades originals en anglès i en un sol treball. -

Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova +41(0)22 91705 +41(0)22 91744 Needs Assessment

UNECE Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Regulatory and procedural barriers to trade in the Republic of Moldova trade barriers to Regulatory and procedural Needs Assessment Needs Assessment Regulatory and Procedural Barriers Regulatory and Procedural to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Trade to Information Service United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNITED NATIONS UNITED Palais des Nations CH - 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland ISBN 978-92-1-117134-1 Telephone: +41(0)22 917 44 44 Fax: +41(0)22 917 05 05 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unece.org Layout and Printing at United Nations, Geneva – 1718053 (E) – August 2017 – 693 – ECE/TRADE/433 UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Needs Assessment United Nations New York and Geneva, 2017 2 Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova: Needs Assessment Note The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. This publication will be issued in English, Romanian and Russian. ECE/TRADE/433 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No.: E.17.II.E.13 ISBN: 978-92-1-117134-1 e-ISBN: 978-92-1-361399-3 Copyright © 2017 United Nations All rights reserved UNITED NATIONS publication issued by the Economic Commission for Europe Foreword 3 Foreword A small landlocked country, the Republic of Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in South East Europe, with the economy showing continued dependence on low value-added manufacturing and agriculture along with remittances from workers abroad for income generation. -

N E W S L E T T E

ISSUE NO. 60 | JULY-AUGUST 2020 N E W S L E T T E R M O L D O V A Transnistria’s economy during the Corona crisis The Transnistrian economy entered 2020 on a bank Moldova) and of goods resulting in additional relatively strong footing. Metal exports and electricity economic damage. production – the two main sectors – showed high Since March: effect of Corona crisis growth after trade restrictions for metals were lifted and a new electricity contract with Chisinau was While no GDP data for the second quarter of 2020 is signed. However, the Corona crisis put an end to the published yet, it becomes ever clearer that the crisis economic upswing. Very strict containment measures, has taken a heavy toll on the Transnistrian economy. a collapse of remittances and external demand have On top of the domestic effect resulting from the led to a severe recession. To make matters worse, the economic lockdown, comes an “external effect” fiscal situation, which was already strained before the resulting from lower external demand and remittances. crisis, means that there is little room for additional According to EUBAM, the value of goods exported from public spending. With no help from monetary policy - the Transnistrian region (including goods sold to right- which is focussed on maintaining the fixed exchange bank Moldova) fell by 15% over the period January to rate - and no access to external financial assistance, June 2020 when compared to the same period of 2019 GDP is estimated to decline by 11% in 2020. While the (which was already very weak). -

List of Countries, Capital & Its Currency

www.gradeup.co List of Countries, Capital & its Currency North America Sr. Country Capital Currency No. 1 Antigua and Barbuda St. John’s East Caribbean dollar 2 Bahamas Nassau Bahamian dollar 3 Barbados Bridgetown Barbadian dollar 4 Belize Belmopan Belize dollar 5 Canada Ottawa Canadian dollar 6 Costa Rica San Jose Costa Rican colon 7 Cuba Havana Cuban peso 8 Dominica Roseau East Caribbean dollar 9 Dominican Republic Santo Domingo Dominican peso 10 El Salvador San Salvador United States dollar 11 Grenada St. George’s East Caribbean dollar 12 Guatemala Guatemala city Guatemalan Quetzal 13 Haiti Port-au-Prince Haitian gourde 14 Honduras Tegucigalpa Honduran Lempira 15 Jamaica Kingston Jamaican dollar 16 Mexico Mexico city Mexican peso 17 Nicaragua Managua Nicaraguan Cordoba 18 Panama Panama City Panamanian Balboa 19 Saint Kitts and Nevis Basseterre East Caribbean dollar 20 Saint Lucia Castries East Caribbean dollar 21 Saint Vincent and the Grenadines Kingstown East Caribbean dollar Trinidad and Tobago 22 Trinidad and Tobago Port of Spain dollar 23 United States Washington, D.C. United States dollar South America Country Capital Currency 1 Argentina Buenos Aires Argentine peso 2 Bolivia Sucre Bolivian Boliviano 3 Brazil Brasilia Brazilian real 4 Chile Santiago Chilean peso 5 Colombia Bogota Colombian peso 6 Ecuador Quito United states dollar 7 Guyana Georgetown Guyanese dollar 8 Paraguay Asuncion Paraguayan guarani www.gradeup.co 9 Peru Lima Peruvian Nuevo sol 10 Suriname Paramaribo Surinamese dollar 11 Uruguay Montevideo Uruguayan peso 12 -

Transnistrian Market and Its Impact on Policy and Economy of the Republic of Moldova

FRIEDRICH EBERT FOUNDATION Transnistrian Market and its Impact on Policy and Economy of the Republic of Moldova Chisinau 2005 Authors: Mikhail Burla, Anatol Gudim, Vladislav Kutyrkin, Galina Selari Scientific editor: Anatol Gudim Evaluations, expressed in the materials, reflect only the point of view of the authors. They do not always coincide with the opinion of the editor and by no means can be considered the opinion of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. 2 Contents Preface…………………………………………………………………….…………5 Introduction………………………………………………………………….………5 1. Transnistria’s Economic System: Interaction between Regional Authorities and Economy…………………………………………..….7 2. Macroeconomic Trends, Main Production Sectors…………………………..…..11 3. External Trade: Import and Export Structure and Direction…………………....14 4. Interaction between the Economies of Transnistria and Russia……………..….19 5. Transnistrian Market: Interaction with Neighbors – Moldova and Ukraine…....22 6. Impact of the Transnistrian Market on Policy and Economy of the Republic of Moldova……………………………………...25 Conclusion………………………………………………………………….…….….28 Annexes…………………………………………………………………….……..…30 References………………………………………………………………….………..48 3 4 Preface The Friedrich Ebert Foundation has initiated the preparation of a study on the economic dimension of the Transnistrian problem, which was realized by the Center for Strategic Studies and Reforms. This publication has to contribute to a greater transparency of the economic situation in this region. We also hope that facts and evaluations, which are contained in the material presented, will make easier coming closer to the resolution of the Transnistrian issue. At the same time, it should be especially mentioned, that the contents of the publication do not represent the opinion of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. I hope that facts, statistical data, and evaluations of this study will give the reader the opportunity to develop some additional arguments, which will contribute to the achievement of a greater democracy and stability in this region of Europe. -

Moldova RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018

Moldova RISK & COMPLIANCE REPORT DATE: March 2018 KNOWYOURCOUNTRY.COM Executive Summary - Moldova Sanctions: None FAFT list of AML No Deficient Countries Not on EU White list equivalent jurisdictions Higher Risk Areas: Corruption Index (Transparency International & W.G.I.) Failed States Index (Political Issues)(Average Score) Non - Compliance with FATF 40 + 9 Recommendations Medium Risk Areas: US Dept of State Money Laundering Assessment Weakness in Government Legislation to combat Money Laundering World Governance Indicators (Average Score) Major Investment Areas: Agriculture - products: vegetables, fruits, grapes, grain, sugar beets, sunflower seed, tobacco; beef, milk; wine Industries: sugar, vegetable oil, food processing, agricultural machinery; foundry equipment, refrigerators and freezers, washing machines; hosiery, shoes, textiles Exports - commodities: foodstuffs, textiles, machinery Exports - partners: Russia 20.9%, Romania 19.8%, Italy 11.6%, Ukraine 6.6%, Turkey 6%, Germany 4.7% (2012) Imports - commodities: mineral products and fuel, machinery and equipment, chemicals, textiles Investment Restrictions: There are no economic or industrial strategies that have a discriminatory effect on foreign- owned investors in Moldova, and no limits on foreign ownership or control, except in the 1 right to purchase and sell agricultural and forest land, which is restricted to Moldovan citizens. The Law on Entrepreneurship and Enterprises has a list of activities restricted solely to state enterprises, which includes, among others, human -

Republic of Moldova Economic Review of Thetransnistria Region Public Disclosure Authorized

Report No. 17886-MD Republic of Moldova Economic Review of theTransnistria Region Public Disclosure Authorized June 1998 Europe and Central Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ] i t Public Disclosure Authorized Currency Equivalents Lei TR- Transnistria Ruble (local currency of the Transnistria region) 1995 (annual average) 1996 (annual average) US$1.00 = Lei 4.49 US$1.00 = Lei 4.60 US$1.00 = TR 61,300 US$1.00 = TR 410,083 1997 (annual average) January 1998 US$1.00 = Lei 4.62 US$1.00 = Lei 4.71 US$1.00 = TR 650,417 US$1.00 = TR 680,000 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS CIS Commonwealth of Independent States ECA Europe and Central Asia Region FSU Former Soviet Union GDP Gross domestic product GOM Government of Moldova NBM National Bank of Moldova OGRF Military contingent of the Russian Federation in Transnistria OSCE Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe PREM Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unit at ECA PRM Parliament of the Republic of Moldova SME Small and medium-size enterprises TDS Transnistrian Department of Statistics TRB Transnistrian Republican Bank TSS Transnistrian Supreme Soviet (regional Parliament) FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Vice President Johannes Linn, ECAVP Country Director Roger Grawe, ECCO7 Sector Leader Hafez Ghanem. ECSPE Responsible Staff James Parks, Resident Representative, ECCMD Elena Nikulina,Economist, ECCMD REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA: ECONOMIC REVIEW OF THE TRANSNISTRIA REGION TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY i CHAPTER I. BACKGROUND 1 A. History 1 B. Territory 2 C. Population 2 D. Economic Importance of the Transnistria Region in Soviet Times 3 E.