The Extraterritorial Application of the European Convention on Human

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnistrian Region December 2015

Regional Economic Review: Transnistrian Region December 2015 Disclaimer This document is published by the Independent Think-Tank Expert-Grup within the Program “Support to Confidence Building Measures”, financed by the EU Delegation in Moldova and implemented by United Nations Development Programme in Moldova. Opinions expressed in this document belong to the authors and are not necessarily the opinions of the donors. Also, the authors are aware of potential risks related to quality of the statistical data and have used the data with due precaution. This document is a translation from the Romanian language. 2 Regional Economic Review: Transnistrian Region December 2015 Contents List of figures .............................................................................................................................................. 3 List of tables ............................................................................................................................................... 3 Key messages of this issue....................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Domestic Supply ...................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter 2. Domestic Demand................................................................................................................. -

0306 Transnistria

Transnistrian Economy: Initiatives and Risks The idea of a federal state suggested by the OSCE so unexpectedly and supported both by the guarantor states, the Republic of Moldova, and Transnistria is gradually “seizing the masses”. First steps were made towards “a common state”: the composition of joint Constitution drafting commission was approved; workshop on federalism was held under the aegis of the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly; the development of the Reintegration Concept is underway. In order to speed up this process it is important to raise potential of mutual understanding and awareness. Searching for a way Before the Republic of Moldova and Transnistria agreed to a future “common state”, the economy of these subregions developed in different ways of trials and mistakes. In Moldova, market reforms started in 1992-1993, but now attempts are being made to strengthen presence of the state in the economy. In TMR, state regulation has always been a preferred method and market processes did not intensify until late 1990s. Generally speaking, the following stages can be distinguished in the economic development of Transnistria: · 1990 – 1991: search for a “free economic zone” model, attempts to implement the “regional self-financing” model suggested by the Baltic republics and popular during perestroika in the USSR. Case for it: large-scale multi-sectoral industry, intensive agriculture, premises for tourism development, and advantages of having transport routes; · 1992: pinnacle of tension in the relations between Chisinau and Tiraspol, military conflict, reciprocal attempts to block the infrastructure: power and gas supply lines, railroads; · 1993 – 1995: search for ways of economic survival without political recognition and with disrupted manufacturing cooperation with the right bank. -

"Frozen" Human Rights in Abkhazia, Transdniestria, and the Donbas: the Role of the OSCE in a Shaky System of Internati

In: IFSH (ed.), OSCE Yearbook 2017, Baden-Baden 2018, pp. 181-200. Lia Neukirch “Frozen” Human Rights in Abkhazia, Transdniestria, and the Donbas: The Role of the OSCE in a Shaky System of International Human Rights Protection Mechanisms Introduction The disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1990 and 1991 led to the formation of several new countries with little or no previous experience of statehood. The national movements in Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine combined their struggle to “escape” the Soviet Union with ambitious pro-Western agendas. At the same time, these struggles over the political direction of the newly created states – whether more towards Moscow or closer to Europe – have been accompanied by powerful secessionist movements that have challenged the territorial integrity of the young states themselves. While the latter were fighting to create their own fragile democracies, separatist military groups carved out the secessionist territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Trans- dniestria, and, most recently, the Lugansk People’s Republic (LPR) and the Donetsk People’s Republic (DPR) in the Donbas region of Ukraine, profiting from political and socio-economic instability and augmenting their power with Russian support to create de facto entities. Both Abkhazia and Transdniestria are considered “classic” frozen con- flicts, while the recent conflict in Donbas is not yet openly referred to as such; the level of violence is still too high, and the political magnitude of the conflict is considered too great for open acceptance, with the result that it might remain unresolved for a prolonged period of time. Nonetheless, it is highly probable that Luhansk and Donetsk will follow the same path as the older frozen conflicts, becoming “another frozen conflict”,1 as President Vladimir Putin of the Russian Federation declared on 13 November 2015. -

Land Violation of Children's Rights in Gali District

No Future Violation of Children’s Rights Land in Gali District Contacts E [email protected] W http://truth-hounds.org/en/ https://www.facebook.com/truthhounds E [email protected] W https://www.nofutureland.org/ https://www.facebook.com/Nofutureland/ Contents Executive Summary 4 Introduction 5 Sources of Information and Methodology of Documentation 7 The Rights of Children to Life and Health 8 Right to Education 12 Freedom of Movement 18 Legal Qualifications 23 The Right to Education 24 Freedom of Movement 25 The Right of Children to Life and Health 26 Conclusion and Recommendations 28 Authors of the Report 29 4 Executive Summary This report presents compelling evidence of human rights violations in occupied Abkhazian territories, specifically in Gali district, a predominantly Georgian part close to the boundary line. As for the time of the publication of this report, the people living in Gali are lacking the opportunity to cross the demarcation line without restrictions, they become victims of arbitrary detentions and illegal imprisonment, have limited accessibility to health services and are forced to apply for an “Abkhazian Passports” to get to work, to travel within and out of the region, etc. The right to education of children living in Gali is also violated. Their right and opportunity to education in their native Georgian language are deprived because Georgian was replaced with Russian at all schools of lower and upper zones of Gali in 2015. Children are the victims of “Russification”, ethnic discrimination and suppression of their Georgian identity. The amount of children crossing the boundary line on a daily basis, to study at schools on Tbilisi-controlled territory, is decreasing with every year. -

THE BENEFITS of ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia's

v53.i4.524.king 9/27/01 5:18 PM Page 524 THE BENEFITS OF ETHNIC WAR Understanding Eurasia’s Unrecognized States By CHARLES KING* AR is the engine of state building, but it is also good for busi- Wness. Historically, the three have often amounted to the same thing. The consolidation of national states in western Europe was in part a function of the interests of royal leaders in securing sufficient rev- enue for war making. In turn, costly military engagements were highly profitable enterprises for the suppliers of men, ships, and weaponry. The great affairs of statecraft, says Shakespeare’s Richard II as he seizes his uncle’s fortune to finance a war, “do ask some charge.” The distinc- tion between freebooter and founding father, privateer and president, has often been far murkier in fact than national mythmaking normally allows. Only recently, however, have these insights figured in discussions of contemporary ethnic conflict and civil war. Focused studies of the me- chanics of warfare, particularly in cases such as Sudan, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, have highlighted the complex economic incentives that can push violence forward, as well as the ways in which the easy labels that analysts use to identify such conflicts—as “ethnic” or “religious,” say—always cloud more than they clarify.1 Yet how precisely does the chaos of war become transformed into networks of profit, and how in turn can these informal networks harden into the institutions of states? Post-Soviet Eurasia provides an enlightening instance of these processes in train. In the 1990s a half dozen small wars raged across the region, a series of armed conflicts that future historians might term collectively the * The author would like to thank three anonymous referees for comments on an earlier draft of this article and Lori Khatchadourian, Nelson Kasfir, Christianne Hardy Wohlforth, Chester Crocker, and Michael Brown for helpful conversations. -

Discordant Neighbours Ii CONTENTS Eurasian Studies Library

CONTENTS i Discordant Neighbours ii CONTENTS Eurasian Studies Library Editors-in-Chief Sergei Bogatyrev School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Dittmar Schorkowitz Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle/Saale, Germany Board Members ildikó bellér-hann – paul bushkovitch – peter finke geoffrey hosking – mikhail khodarkovsky marlène laruelle – virginia martin david schimmelpenninck van der oye – willard sunderland VOLUME 3 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/esl CONTENTS iii Discordant Neighbours A Reassessment of the Georgian-Abkhazian and Georgian-South Ossetian Conflicts By George Hewitt LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Coveriv illustration: Whilst the map on the front-coverCONTENTS delineates the frontiers of the former Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic, the areas in green represent the republics of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as recognised by Russia (26 August 2008) and five other UN member-states; red indicates the territory subject to the writ of the Georgian government and thus the reduced frontiers of today’s Republic of Georgia. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hewitt, B. G. Discordant neighbours : a reassessment of the Georgian-Abkhazian and Georgian-South- Ossetian conflicts / by George Hewitt. pages cm. -- (Eurasian studies library, ISSN 1877-9484 ; volume 3) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-24892-2 (hardback : acid-free paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-24893-9 (e-book) 1. Georgia (Republic)--Relations--Georgia--Abkhazia. 2. Georgia (Republic)--Relations--Georgia-- South Ossetia. 3. Abkhazia (Georgia)--Relations--Georgia (Republic) 4. South Ossetia (Georgia)-- Relations--Georgia (Republic) 5. Ethnic conflict--Georgia. 6. Georgia (Republic)--Ethnic relations. 7. Georgia (Republic)--History--1991- 8. -

Executive Summary Since Its Independence in 1991, Moldova, A

Executive Summary Since its independence in 1991, Moldova, a former Soviet republic, has made significant progress towards adopting the principles of a free market democracy. However, it has a mixed record of reforms over the years with past practices afflicting its public and private sectors and showcasing its institutional weaknesses. The political turmoil of 2013 highlighted the major shortcomings of its business environment and governmental practices despite a declared understanding of the need for more foreign direct investment. Controversies in the banking and financial sectors and questionable governmental decisions conceding control in several key sectors rocked the country. Despite slight progress reported by the latest World Bank Survey on Ease of Doing Business, recent efforts to tackle corruption, increase transparency in decision-making, cut bureaucracy, and uphold the rule of law have yet to make significant improvements in the investment climate. A new government was created in 2013, which continued the previous government’s path toward greater integration with the EU. The government initialed its Association Agreement (AA) with the EU, including a deep and comprehensive free trade agreement (DCFTA), in November 2013. With the signing of the AA expected to occur no later than early autumn of 2014, Moldova will be firmly set on a course of deeper reforms to bring its governmental, regulatory, and business practices in line with EU standards. The implementation of the DCFTA will integrate Moldova further into the EU market and create more opportunities for investment as a bridge between the vast markets of the EU and former Soviet republics. The business climate remains challenging. -

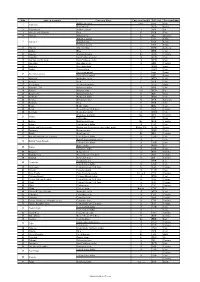

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Georgia: a Gap Analysis

Protection of Internally Displaced Persons in Georgia: A Gap Analysis This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of the European Union. July 2009 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS..................................................................................................................................... 2 List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Executive Summary............................................................................................................................................. 6 1. Context ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 1.1. Demographic profile .......................................................................................................................... 10 1.2. Meaningful participation.................................................................................................................... 10 1.3. Solution Oriented Approach .............................................................................................................. 11 1.5.1. Focus on return as the only durable solution ................................................................................. 11 1.5.2. Humanitarian space and access..................................................................................................... -

Security Council Distr

UNITED NATIONS S Security Council Distr. GENERAL S/26795 17 November 1993 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Note by the Secretary-General The attached document contains the report of the fact-finding mission that I dispatched in October 1993 to investigate the situation of human rights violations in Abkhazia, Republic of Georgia, including reports of "ethnic cleansing". My decision to send the mission was welcomed by the Security Council in operative paragraph 4 of its resolution 876 (1993) of 19 October 1993. The mission visited the area from 22 to 30 October 1993. 93-64274 (E) 231193 /... S/26795 English Page 2 Annex Report of the Secretary-General’s fact-finding mission to investigate human rights violations in Abkhazia, Republic of Georgia INTRODUCTION 1. Following reports of violations of human rights in Abkhazia, Republic of Georgia, and urgent requests to me to ascertain their nature and extent, in October I decided to dispatch a fact-finding mission to investigate the situation of human rights violations in Abkhazia, including reports of "ethnic cleansing". 2. The Security Council, in its resolution 876 (1993), welcomed that decision. In its resolution 881 (1993), the Council reiterated its demand in its resolution 876 (1993) that all parties to the conflict in Abkhazia, Republic of Georgia, refrain from the use of force and from any violation of international humanitarian law, and looked forward to the report of the fact-finding mission. 3. The mission visited the area from 22 to 30 October 1993. It was headed by the Chief of the International Instruments Section of the Centre for Human Rights, who was assisted by two Professional staff members, one from the Centre in Geneva and the other from the Department of Political Affairs in New York. -

Viktoria Potapkina

Nation Building in Contested States Viktoria Potapkina TESI DOCTORAL UPF/ANY 2018 DIRECTOR DE LA TESI Dr. Klaus-Jürgen Nagel DEPARTAMENT DE CIENCIES POLITIQUES I SOCIALS For My Family Acknowledgments I am grateful to UPF for being my academic “home” during the time I spent writing this thesis. I want to thank all the professors for their advice, critique and guidance. It was a long, but greatly enriching venture. My utmost gratitude goes to my supervisor, Dr. Klaus-Jürgen Nagel, who generously offered his time and expertise to discuss my work with me. I am thankful for his invaluable suggestions, endless encouragement, deliberation and guidance from day one. I would like to thank my friends and colleagues, who took the time to discuss my research with me, read various drafts and chapters, and generally supported me every step of the way. I am grateful to all the people who took their time to share their insight and observations with me in and about Northern Cyprus and Kosovo during the time I spent there. Finally, I would like to thank my family who have supported me during this uneasy process. My most sincere thanks go to my parents, grandparents and brother, who have provided me with unconditional support and encouragement. This thesis would not have been possible without their unfailing support. v vi Resum (Catalan) Aquesta tesi consisteix en una anàlisi dels processos de construcció nacional (nation-building) actuals. Centrada específicament en els casos de la República Turca del Nord de Xipre, la República Moldava de Pridnestroviana i Kosovo, es basa en dades originals en anglès i en un sol treball. -

Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova +41(0)22 91705 +41(0)22 91744 Needs Assessment

UNECE Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Regulatory and procedural barriers to trade in the Republic of Moldova trade barriers to Regulatory and procedural Needs Assessment Needs Assessment Regulatory and Procedural Barriers Regulatory and Procedural to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Trade to Information Service United Nations Economic Commission for Europe UNITED NATIONS UNITED Palais des Nations CH - 1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland ISBN 978-92-1-117134-1 Telephone: +41(0)22 917 44 44 Fax: +41(0)22 917 05 05 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unece.org Layout and Printing at United Nations, Geneva – 1718053 (E) – August 2017 – 693 – ECE/TRADE/433 UNITED NATIONS ECONOMIC COMMISSION FOR EUROPE Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova Needs Assessment United Nations New York and Geneva, 2017 2 Regulatory and Procedural Barriers to Trade in the Republic of Moldova: Needs Assessment Note The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. This publication will be issued in English, Romanian and Russian. ECE/TRADE/433 UNITED NATIONS PUBLICATION Sales No.: E.17.II.E.13 ISBN: 978-92-1-117134-1 e-ISBN: 978-92-1-361399-3 Copyright © 2017 United Nations All rights reserved UNITED NATIONS publication issued by the Economic Commission for Europe Foreword 3 Foreword A small landlocked country, the Republic of Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in South East Europe, with the economy showing continued dependence on low value-added manufacturing and agriculture along with remittances from workers abroad for income generation.