Discordant Neighbours Ii CONTENTS Eurasian Studies Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Russia-Georgia Relations

russian analytical russian analytical digest 68/09 digest the moment. So are specific steps aimed at resolving the usually are not focused on activities that cannot bring Abkhazia and South Ossetia conflicts. Harm reduction anything tangible in the short run. is the only realistic policy objective in that area. As to the long run, one should admit that nobody At the same time, Georgia cannot afford to lose ties can confidently predict what will be happening in the to the people who live in Abkhazia and South Ossetia region in ten–fifteen years time or beyond that. Georgia now – whatever political attitudes they may have. This has too much on its hands right now to be too involved is not easy, but Georgians – both in government and in speculations about it. It is rational to focus on ob- in society – should be creative and inventive on this jectives that can be achieved and not allow things that point. Apart from technical impediments for such con- cannot be changed for the time being to get one de- tacts, the trick is that there can be no short-term politi- pressed. cal advantages coming from such contacts, and people About the Author: Professor Ghia Nodia is the Director of the School of Caucasus Studies at Ilia Chavchavadze State University in Tbilisi, Georgia and chairman of the Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development, a Georgian think-tank. Georgian Attitudes to Russia: Surprisingly Positive By Hans Gutbrod and Nana Papiashvili, Tbilisi Abstract What do Georgians think about Russia? What relationship would they like to have with their northern neighbor? And what do they think about the August conflict? Data collected by the Caucasus Research Resource Center (CRRC) allows a nuanced answer to these questions: although Georgians have a very crit- ical view of Russia’s role in the August conflict, they continue to desire a good political relationship with their northern neighbor, as long as this is not at the expense of close ties with the West. -

"Two Hagiographic Notes St. Simon – Apostle of Cimmerian Bosporus

Andrey Yu. Vinogradov TWO HAGIOGRAPHIC NOTES ST. SIMON – APOSTLE OF CIMMERIAN BOSPORUS BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: HUMANITIES WP BRP 127/HUM/2016 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE Andrey Yu. Vinogradov1 TWO HAGIOGRAPHIC NOTES ST. SIMON – APOSTLE OF CIMMERIAN BOSPORUS? The article is dedicated to two topics. One is the legend about Apostle Simon, who preached on Cymmerian Bosporus according a 4th-c. tradition later forgotten and replaced by the legend about Apostle Andrew, where Simon was only one of his companions. The second part is concerning future critical edition of the Martyrium of St. Marina including classification of its manuscripts. Keywords: hagiography, Byzantium, Apostle Simon, St. Marina, Bosporos, Caucasus, Crimea, manuscripts, critical edition JEL Classification: Z. 1 National Research University Higher School of Economics. School of history, Associate Professor; Email: [email protected]. A Byzantine hagiographer Epiphanios the Monk, who visited in 815–820 southern, eastern and northern shores of the Black Sea searching for the relics of saints2, describes in his ‘Life of Apostle Andrew’, somewhat unexpectedly, two tombs of apostle Simon found by him: “The Bosporans... showed to us... a shrine with the inscription of ‘Simon the Apostle’, immured in the basement of a very large church of Holy Apostles, with the relics, and gave from them to us; there is also another tomb in Nikopsis of Zikhia, with the inscription of ‘Simon the Cananite’, and it has also the relics”3. -

Distribution: EG: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Burs

Subgenus Lasius Fabricius, 1804 53. L. (Lasius) alienus (Foerster, 1850) Distribution: E.G.: Bank of Jandara Lake, Bolnisi, Bursachili, Gardabani, Grakali, Gudauri, Gveleti, Igoeti, Iraga, Kasristskali, Kavtiskhevi, Kazbegi, Kazreti, Khrami gorge, Kianeti, Kitsnisi, Kojori, Kvishkheti, Lagodekhi Reserve, Larsi, Lekistskali gorge, Luri, Manglisi, Mleta, Mtskheta, Nichbisi, Pantishara, Pasanauri, Poladauri, Saguramo, Sakavre, Samshvilde, Satskhenhesi, Shavimta, Shulaveri, Sighnaghi, Taribana, Tbilisi (Mushtaidi Garden, Tbilisi Botanical Garden), Tetritskaro, Tkemlovani, Tkviavi, Udabno, Zedazeni (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1964a, b, 1966, 1967b, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Abasha, Ajishesi, Akhali Atoni, Anaklia, Anaria, Baghdati, Batumi Botanical Garden, Bichvinta Reserve, Bjineti, Chakvi, Chaladidi, Chakvistskali, Eshera, Grigoreti, Ingiri, Inkiti Lake, Kakhaberi, Khobi, Kobuleti, Kutaisi, Lidzava, Menji, Nakalakebi, Natanebi, Ochamchire, Oni, Poti, Senaki, Sokhumi, Sviri, Tsaishi, Tsalenjikha, Tsesi, Zestaponi, Zugdidi Botanical Garden (Ruzsky, 1905; Karavaiev, 1926; Jijilashvili, 1974b); S.G.: Abastumani, Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, Aspindza, Avralo, Bakuriani, Bogdanovka, Borjomi, Dmanisi, Goderdzi Pass, Gogasheni, Kariani, Khanchali Lake, Ota, Paravani Lake, Sapara, Tabatskuri, Trialeti, Tsalka, Zekari Pass (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1967a, 1974a). 54. L. (Lasius) brunneus (Latreille, 1798) Distribution: E.G.: Bolnisi, Gardabani, Kianeti, Kiketi, Manglisi, Pasanauri (Ruzsky, 1905; Jijilashvili, 1968, 1974a); W.G.: Akhali Atoni, Baghdati, -

Economic Prosperity Initiative

USAID/GEORGIA DO2: Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth October 1, 2011 – September 31, 2012 Gagra Municipal (regional) Infrastructure Development (MID) ABKHAZIA # Municipality Region Project Title Gudauta Rehabilitation of Roads 1 Mtskheta 3.852 km; 11 streets : Mtskheta- : Mtanee Rehabilitation of Roads SOKHUMI : : 1$Mestia : 2 Dushet 2.240 km; 7 streets :: : ::: Rehabilitation of Pushkin Gulripshi : 3 Gori street 0.92 km : Chazhashi B l a c k S e a :%, Rehabilitaion of Gorijvari : 4 Gori Shida Kartli road 1.45 km : Lentekhi Rehabilitation of Nationwide Projects: Ochamchire SAMEGRELO- 5 Kareli Sagholasheni-Dvani 12 km : Highway - DCA Basisbank ZEMO SVANETI RACHA-LECHKHUMI rehabilitaiosn Roads in Oni Etseri - DCA Bank Republic Lia*#*# 6 Oni 2.452 km, 5 streets *#Sachino : KVEMO SVANETI Stepantsminda - DCA Alliance Group 1$ Gali *#Mukhuri Tsageri Shatili %, Racha- *#1$ Tsalenjikha Abari Rehabilitation of Headwork Khvanchkara #0#0 Lechkhumi - DCA Crystal Obuji*#*# *#Khabume # 7 Oni of Drinking Water on Oni for Nakipu 0 Likheti 3 400 individuals - Black Sea Regional Transmission ZUGDIDI1$ *# Chkhorotsku1$*# ]^!( Oni Planning Project (Phase 2) Chitatskaro 1$!( Letsurtsume Bareuli #0 - Georgia Education Management Project (EMP) Akhalkhibula AMBROLAURI %,Tsaishi ]^!( *#Lesichine Martvili - Georgia Primary Education Project (G-Pried) MTSKHETA- Khamiskuri%, Kheta Shua*#Zana 1$ - GNEWRC Partnership Program %, Khorshi Perevi SOUTH MTIANETI Khobi *# *#Eki Khoni Tskaltubo Khresili Tkibuli#0 #0 - HICD Plus #0 ]^1$ OSSETIA 1$ 1$!( Menji *#Dzveli -

FÁK Állomáskódok

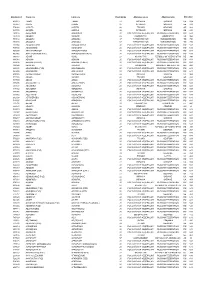

Állomáskód Orosz név Latin név Vasút kódja Államnév orosz Államnév latin Államkód 406513 1 МАЯ 1 MAIA 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 085827 ААКРЕ AAKRE 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 574066 ААПСТА AAPSTA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 085780 ААРДЛА AARDLA 26 ЭСТОНИЯ ESTONIA EE 233 269116 АБАБКОВО ABABKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 737139 АБАДАН ABADAN 29 УЗБЕКИСТАН UZBEKISTAN UZ 860 753112 АБАДАН-I ABADAN-I 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 753108 АБАДАН-II ABADAN-II 67 ТУРКМЕНИСТАН TURKMENISTAN TM 795 535004 АБАДЗЕХСКАЯ ABADZEHSKAIA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 795736 АБАЕВСКИЙ ABAEVSKII 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 864300 АБАГУР-ЛЕСНОЙ ABAGUR-LESNOI 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 865065 АБАГУРОВСКИЙ (РЗД) ABAGUROVSKII (RZD) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 699767 АБАИЛ ABAIL 27 КАЗАХСТАН REPUBLIC OF KAZAKHSTAN KZ 398 888004 АБАКАН ABAKAN 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 888108 АБАКАН (ПЕРЕВ.) ABAKAN (PEREV.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 398904 АБАКЛИЯ ABAKLIIA 23 МОЛДАВИЯ MOLDOVA, REPUBLIC OF MD 498 889401 АБАКУМОВКА (РЗД) ABAKUMOVKA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 882309 АБАЛАКОВО ABALAKOVO 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 408006 АБАМЕЛИКОВО ABAMELIKOVO 22 УКРАИНА UKRAINE UA 804 571706 АБАША ABASHA 28 ГРУЗИЯ GEORGIA GE 268 887500 АБАЗА ABAZA 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 887406 АБАЗА (ЭКСП.) ABAZA (EKSP.) 20 РОССИЙСКАЯ ФЕДЕРАЦИЯ RUSSIAN FEDERATION RU 643 -

Security Council Distr.: General 18 July 2007

United Nations S/2007/439 Security Council Distr.: General 18 July 2007 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on the situation in Abkhazia, Georgia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to Security Council resolution 1752 (2007) of 13 April 2007, by which the Security Council decided to extend the mandate of the United Nations Observer Mission in Georgia (UNOMIG) until 15 October 2007. It provides an update of the situation in Abkhazia, Georgia since my report of 3 April 2007 (S/2007/182). 2. My Special Representative, Jean Arnault, continued to lead the Mission. He was assisted by the Chief Military Observer, Major General Niaz Muhammad Khan Khattak (Pakistan). The strength of UNOMIG on 1 July 2007 stood at 135 military observers and 16 police officers (see annex). II. Political process 3. During the reporting period, UNOMIG continued efforts to maintain peace and stability in the zone of conflict. It also sought to remove obstacles to the resumption of dialogue between the Georgian and Abkhaz sides in the expectation that cooperation on security, the return of internally displaced persons and refugees, economic rehabilitation and humanitarian issues would facilitate meaningful negotiations on a comprehensive political settlement of the conflict, taking into account the principles contained in the document entitled “Basic Principles for the Distribution of Competences between Tbilisi and Sukhumi”, its transmittal letter (see S/2002/88, para. 3) and additional ideas by the sides. 4. Throughout the reporting period, my Special Representative maintained regular contact with both sides, as well as with the Group of Friends of the Secretary-General both in Tbilisi and in their capitals. -

Russia, Georgia and the Eu in Abkhazia and South Ossetia

PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION: RUSSIA, GEORGIA AND THE EU IN ABKHAZIA AND SOUTH OSSETIA Iskra Kirova August 2012 Figueroa Press Los Angeles The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author and cannot be interpreted to reflect the positions of organizations that the author is affiliated with. PUBLIC DIPLOMACY AND CONFLICT RESOLUTION: RUSSIA, GEORGIA AND THE EU IN ABKHAZIA AND SOUTH OSSETIA Iskra Kirova Published by FIGUEROA PRESS 840 Childs Way, 3rd Floor Los Angeles, CA 90089 Phone: (213) 743-4800 Fax: (213) 743-4804 www.figueroapress.com Figueroa Press is a division of the USC Bookstore Copyright © 2012 all rights reserved Notice of Rights All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior written permission from the author, care of Figueroa Press. Notice of Liability The information in this book is distributed on an “As is” basis, without warranty. While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, neither the author nor Figueroa nor the USC Bookstore shall have any liability to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by any text contained in this book. Figueroa Press and the USC Bookstore are trademarks of the University of Southern California ISBN 13: 978-0-18-214016-9 ISBN 10: 0-18-214016-4 For general inquiries or to request additional copies of this paper please contact: USC Center on Public Diplomacy at the Annenberg School University of Southern California 3502 Watt Way, G4 Los Angeles, CA 90089-0281 Tel: (213) 821-2078; Fax: (213) 821-0774 [email protected] www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org CPD Perspectives on Public Diplomacy CPD Perspectives is a periodic publication by the USC Center on Public Diplomacy, and highlights scholarship intended to stimulate critical thinking about the study and practice of public diplomacy. -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Terms of Reference Delivering the Virtual Trainings on Media Literacy June-July 2021

Terms of Reference Delivering the virtual Trainings on Media Literacy June-July 2021 Europe Foundation invites proposals from qualified organizations or individual/s to conduct a virtual training on Media Literacy for youth engaged in the Foundation’s Youth Integration Program. The objective of the training is to hone the participants’ skills in accessing, critically assessing, and creating media content, to make their social and civic activism more effective. Europe Foundation expects this assignment to be conducted between June-July 2021, depending upon the availability of the selected consultant/s. About Europe Foundation Europe Foundation’s mission is to empower people to effect change for social justice and economic prosperity through hands-on programs, helping them to improve their communities and their own lives. To achieve its mission, Europe Foundation strives to strengthen the capacity of individuals and institutions, empowering them to address pressing issues and to mobilize relevant stakeholders in issue-based dialogue, through raising public awareness and creating various coalitions, platforms or working groups, so as to effect positive change. Program Background Information The Europe Foundation’s Youth Integration Program strives to increase youth volunteerism and civic engagement to address targeted communities’ needs. The Foundation employs the Youth Bank (YB) methodology, an innovative way of increasing youth participation through creating groups of young people (aged 15-21) in a given community and empowering them with training and resources to find, fund, and oversee small youth-led initiatives that address salient for local communities’ issues. The YB concept is founded on the premise that involving young people in projects they design and manage is the most potent way to develop civic participation among youth. -

Donations to the Library 2000S

DONATIONS TO THE LIDRARY 277 DONATIONS TO THE LIBRARY Michael Andrews (BA 1960) The birth of Europe, 1991; The flight of the condor, 1982; The life that lives on Man, 1977 13 May 1999 - 12 May 2000 Anthony Avis (BA 1949) The Librarian is always delighted to hear from any member of the Gaywood past: some historical notes, 1999; The journey: reflective essays, College considering a gift of books, manuscripts, maps or photographs 1999 to the College Library. Brigadier David Baines Abdus Salam International Centre Documents relating to the army career of Alan Menzies Hiller A. M. Hamende (ed.), Tribute to Abdus Salam (Abdus Salam Memorial (matric. 1913), who was killed in action near Arras in May 1915 meeting, 19-22 Nov. 1997), 1999 D.M. P. Barrere (BA 1966) David Ainscough Georges Bernanos, 'Notes pour ses conferences' (MS), n. d. Chambers' guide to the legal profession 1999-2000, 1999 P. J. Toulet, La jeune fille verte, 1918 Robert Ganzo, Histoire avant Sumer, 1963; L'oeuvre poetique, 1956 Dr Alexander G. A.) Romain Rolland, De Jean Christophe a Colas Breugnon: pages de journal, Automobile Association, Ordnance Survey illustrated atlas of Victorian 1946; La Montespan: drame en trois actes, 1904 and Edwardian Britain, 1991 Ann MacSween and Mick Sharp, Prehistoric Scotland, 1989 Martyn Barrett (BA 1973) Antonio Pardo, The world of ancient Spain, 1976 Martyn Barrett (ed.), The development of language, 1999 Edith Mary Wightrnan, Galla Belgica, 1985 Gerard Nicolini, The ancient Spaniards, 1974 Octavian Basca Herman Ramm, The Parisi, 1978 Ion Purcaru and Octavian Basca, Oameni, idei, fapte din istoria J. -

Ethnobiology of Georgia

SHOTA TUSTAVELI ZAAL KIKVIDZE NATIONAL SCIENCE FUNDATION ILIA STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS ETHNOBIOLOGY OF GEORGIA ISBN 978-9941-18-350-8 Tbilisi 2020 Ethnobiology of Georgia 2020 Zaal Kikvidze Preface My full-time dedication to ethnobiology started in 2012, since when it has never failed to fascinate me. Ethnobiology is a relatively young science with many blank areas still in its landscape, which is, perhaps, good motivation to write a synthetic text aimed at bridging the existing gaps. At this stage, however, an exhaustive representation of materials relevant to the ethnobiology of Georgia would be an insurmountable task for one author. My goal, rather, is to provide students and researchers with an introduction to my country’s ethnobiology. This book, therefore, is about the key traditions that have developed over a long history of interactions between humans and nature in Georgia, as documented by modern ethnobiologists. Acknowledgements: I am grateful to my colleagues – Rainer Bussmann, Narel Paniagua Zambrana, David Kikodze and Shalva Sikharulidze for the exciting and fruitful discussions about ethnobiology, and their encouragement for pushing forth this project. Rainer Bussmann read the early draft of this text and I am grateful for his valuable comments. Special thanks are due to Jana Ekhvaia, for her crucial contribution as project coordinator and I greatly appreciate the constant support from the staff and administration of Ilia State University. Finally, I am indebted to my fairy wordmother, Kate Hughes whose help was indispensable at the later stages of preparation of this manuscript. 2 Table of contents Preface.......................................................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter 1. A brief introduction to ethnobiology...................................................................................... -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover.