Urban Food Forest FINAL Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Native Plant Press

Native Plant Press January 2020 The Native Plant Press The Newsletter of the Central Puget Sound Chapter of WNPS Volume 21 No. 11 January 2020 Holiday Party Recap On Sunday, December 8th, the Central Puget Sound Chapter held our annual holiday party. The event was a potluck, and the fare was wide-ranging and excellent. The native plant-focused silent auction offered several hand-made wreaths, numerous potted natives from tiny succulents to gangly shrubs, plant-themed books and ephemera, and a couple of experiences. The selection occasioned some intense bidding wars, with Franja Bryant and Sharon Baker arriving at a compromise in their battle over the Native Garden Tea Party. A highlight of the party was the presentation of awards to Member, Steward and Professional of the Year. Each year, nominations are submitted by members and the recipients are chosen by the CPS Board. Stewart Wechsler (left) was chosen Member of the Year. Stewart is a Botany Fellow for the chapter and for many years has offered well-attended plant ID sessions before our westside meetings. In addition, he often fields the many botanical questions that we receive from the public. David Perasso (center) is our Steward of the Year. David is a Native Plant Steward at Martha Washington Park on Lake Washington and has been working to restore the historic oak/camas prairie ecosystem at the site. The site is now at the stage where David was able to host a First Nation camas harvest recently. He is also an active volunteer at our native plant nursery, providing vital expertise in the identification and propagation of natives. -

Food Forests: Their Services and Sustainability

Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development ISSN: 2152-0801 online https://foodsystemsjournal.org Food forests: Their services and sustainability Stefanie Albrecht a * Leuphana University Lüneburg Arnim Wiek b Arizona State University Submitted July 29, 2020 / Revised October 22, 2020, and February 8, 2021 / Accepted Febuary 8, 2021 / Published online July 10, 2021 Citation: Albrecht, S., & Wiek, A (2021). Food forests: Their services and sustainability. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 10(3), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2021.103.014 Copyright © 2021 by the Authors. Published by the Lyson Center for Civic Agriculture and Food Systems. Open access under CC-BY license. Abstract detailed insights on 14 exemplary food forests in Industrialized food systems use unsustainable Europe, North America, and South America, practices leading to climate change, natural gained through site visits and interviews. We resource depletion, economic disparities across the present and illustrate the main services that food value chain, and detrimental impacts on public forests provide and assess their sustainability. The health. In contrast, alternative food solutions such findings indicate that the majority of food forests as food forests have the potential to provide perform well on social-cultural and environmental healthy food, sufficient livelihoods, environmental criteria by building capacity, providing food, services, and spaces for recreation, education, and enhancing biodiversity, and regenerating soil, community building. This study compiles evidence among others. However, for broader impact, food from more than 200 food forests worldwide, with forests need to go beyond the provision of social- cultural and environmental services and enhance a * Corresponding author: Stefanie Albrecht, Doctoral student, their economic viability. -

City of Seattle Edward B

City of Seattle Edward B. Murray, Mayor Finance and Administrative Services Fred Podesta, Director July 25, 2016 The Honorable Tim Burgess Seattle City Hall 501 5th Ave. Seattle, WA 98124 Councilmember Burgess, Attached is an annual report of all real property under City ownership. The annual review supports strategic management of the City’s real estate holdings. Because City needs change over time, the annual review helps create opportunities to find the best municipal use of each property or put it back into the private sector to avoid holding properties without an adopted municipal purpose. Each January, FAS initiates the annual review process. City departments with jurisdiction over real property assure that all recent acquisitions and/or dispositions are accurately represented, and provide current information about each property’s current use, and future use, if identified. Each property is classified based on its level of utilization -- from Fully Utilized Municipal Use to Surplus. In addition, in 2015 and 2016, in conjunction with CBO, OPI, and OH, FAS has been reviewing properties with the HALA recommendation on using surplus property for housing. The attached list has a new column that groups excess, surplus, underutilized and interim use properties into categories to help differentiate the potential for various sites. Below is a matrix which explains the categorization: Category Description Difficult building site Small, steep and/or irregular parcels with limited development opportunity Future Use Identified use in the future -

The Cape Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations August 2014 The aC pe Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially Responsive Design N Jonathan Unaka University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Architecture Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Unaka, N Jonathan, "The aC pe Verde Project: Teaching Ecologically Sensitive and Socially Responsive Design" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 572. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/572 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AND SOCIALLY RESPONSIVE DESIGN THE CAPE VERDE PROJECT by N Jonathan Unaka A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Architecture at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee August, 2014 Abstract TEACHING ECOLOGICALLY SENSITIVE AND SOCIALLY RESPONSIVE DESIGN THE CAPE VERDE PROJECT by N Jonathan Unaka The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, August, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor D Michael Utzinger This dissertation chronicles an evolving teaching philosophy. It was an attempt to develop a way to teach ecological design in architecture informed by ethical responses to ecological devastation and social injustice. The world faces numerous social and ecological challenges at global scales. Recent Industrialization has brought about improved life expectancies and human comforts, coinciding with expanded civic rights and personal freedom, and increased wealth and opportunities. -

Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota (H1558)

H1558 (Revised June 2019) Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota TH DAK R OT O A N Dear Friends, We are excited to bring you this publication. Its aim is to help you establish a fruit orchard in your community. Such a project combines horticulture, nutrition, community vitality, maybe even youth. All of these are areas in which NDSU Extension has educational focuses. Local community orchard projects can improve the health of those who enjoy its bounty. This Starting a Community Orchard in North Dakota publication also is online at www.ag.ndsu.edu/publications/lawns-gardens-trees/starting-a-community- orchard-in-north-dakota so you can have it in a printable PDF or mobile-friendly version if you don’t have the book on hand. True to our mission, NDSU Extension is proud to empower North Dakotans to improve their lives and communities through science-based education by providing this publication. We also offer many other educational resources focused on other horticultural topics such as gardening, lawns and trees. If you’re especially passionate about horticulture and sharing your knowledge, consider becoming an NDSU Extension Master Gardener. After training, as a Master Gardener volunteer, you will have the opportunity to get involved in a wide variety of educational programs related to horticulture and gardening in your local community by sharing your knowledge and passion for horticulture! Learn about NDSU Extension horticulture topics, programs, publications and more at www.ag.ndsu.edu/extension/lawns_gardens_trees. We hope this publication is a valuable educational resource as you work with community orchards in North Dakota. -

Consultation on Draft Food Growing Strategy

CONSULTATION ON DRAFT FOOD GROWING STRATEGY Report by Executive Director, Finance and Regulatory EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE 15 September 2020 1 PURPOSE AND SUMMARY 1.1. Following the legislative requirements set out in Part 9 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015, this report introduces Scottish Borders Council’s first ever Food Growing Strategy – ‘Cultivating Communities’ and seeks approval for consultation on the Draft Strategy. This report also sets out the process and next steps in delivering on the Strategy Action Plan, as well as associated changes to Allotment management –including new Allotment Regulations - as required by the legislation. 1.2. The Food Growing Strategy supports the Locality Plans for the region and is itself supported with the proposed creation of new policy EP17 in the Local Development Plan. 1.3 The Consultation Draft Food Growing Strategy was proposed to be brought to Executive on March 17th 2020. However due to Covid-19, this has been delayed. This paper now brings the Draft Strategy, and proposed Allotment Regulations, to Executive for approval for consultation and resourcing. 2 RECOMMENDATIONS 2.1 It is recommended that the Executive Committee:- (a) Approves the Draft Strategy for Consultation (b) Approves the proposals for resourcing as set out in 9.1 (c) Approves the proposed statutory consultation on the new Allotment Regulations Executive Committee – 15 September 2020 3 BACKGROUND 3.1 Part 9 of the Community Empowerment (Scotland) Act 2015 updates and simplifies allotments legislation, bringing it together in a single instrument, introducing new duties on local authorities to increase transparency on the actions taken to provide allotments in their area and limit waiting times. -

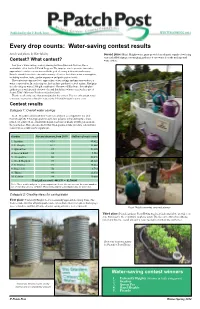

Every Drop Counts: Water-Saving Contest Results

Published by the P-Patch Trust WINTER/SPRING 2012 Every drop counts: Water-saving contest results Article and photos by Nate Moxley Second place: Hazel Heights water gurus provided an adequate supply of watering cans and added signage encouraging gardeners to use water from the underground Contest? What contest? water cistern. Last year’s water-saving contest, running between June and October, was a worthwhile effort for the P-Patch Program. The impetus was to promote innovative approaches to water conservation with the goal of saving both water and money. Results varied from site to site with a variety of factors that affect water consumption, including weather, leaks, garden expansion and participation levels. The contest encompassed two approaches: water savings and innovative ideas for water conservation. In each category, the top three gardens received a prize. First prize in each category was a $100 gift certificate to Greenwood Hardware. Second-place gardens got a variety pack of new tools, and third-place winners received a copy of Seattle Tilth’s Maritime Northwest Garden Guide. Thanks to all of the sites that participated in the contest. You not only spread water conservation awareness but also reduced the P-Patch Program’s water costs. Contest results Category 1: Overall water savings In all, 30 gardens decreased their water consumption as compared to last year. Even though the P-Patch program brought new gardens online during the contest period, we achieved an overall reduction in water use of nearly 20,000 gallons from the year before. This outcome shows that when gardeners take an active role in water conservation, results can be significant. -

Soil Nutrient Management in Haiti, Pre-Columbus to the Present Day: Lessons for Future Agricultural Interventions Remy N Bargout and Manish N Raizada*

Bargout and Raizada Agriculture & Food Security 2013, 2:11 http://www.agricultureandfoodsecurity.com/content/2/1/11 REVIEW Open Access Soil nutrient management in Haiti, pre-Columbus to the present day: lessons for future agricultural interventions Remy N Bargout and Manish N Raizada* Abstract One major factor that has been reported to contribute to chronic poverty and malnutrition in rural Haiti is soil infertility. There has been no systematic review of past and present soil interventions in Haiti that could provide lessons for future aid efforts. We review the intrinsic factors that contribute to soil infertility in modern Haiti, along with indigenous pre-Columbian soil interventions and modern soil interventions, including farmer-derived interventions and interventions by the Haitian government and Haitian non-governmental organizations (NGOs), bilateral and multilateral agencies, foreign NGOs, and the foreign private sector. We review how agricultural soil degradation in modern Haiti is exacerbated by topology, soil type, and rainfall distribution, along with non- sustainable farming practices and poverty. Unfortunately, an ancient strategy used by the indigenous Taino people to prevent soil erosion on hillsides, namely, the practice of building conuco mounds, appears to have been forgotten. Nevertheless, modern Haitian farmers and grassroots NGOs have developed methods to reduce soil degradation. However, it appears that most foreign NGOs are not focused on agriculture, let alone soil fertility issues, despite agriculture being the major source of livelihood in rural Haiti. In terms of the types of soil interventions, major emphasis has been placed on reforestation (including fruit trees for export markets), livestock improvement, and hillside erosion control. -

Growing Urban Orchards

GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS THE UPS, DOWNS AND HOW-TOS OF FRUIT TREE CARE IN THE CITY GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City by Susan Poizner Dedicated to Sherry, Lynn and all the volunteers of the Ben Nobleman Park Community Orchard. Growing Urban Orchards: The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner Illustrations: Sherry Firing Copy Editors: Jack Kirchhoff, Lynn Nicholas Design: Bungalow Publisher: Orchard People (2359434 Ontario Inc.): 107 Everden Road, Toronto, ON M6C 3K7 Canada www.urbanfruittree.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or me- chanical, including photocopying, recording or by any informa- tion storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review. Copyright: 2014 Orchard People (2359434 Ontario Inc.): First Edition, 2014 Published in Canada Growing Urban Orchards The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner Growing Urban Orchards The Ups, Downs and How-tos of Fruit Tree Care in the City By Susan Poizner GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS Table of Contents Part 1: Introduction Chapter 1: Discovering Urban Orchards 3 Chapter 2: Selecting Your Site 7 Site Preparation 8 Orchard Inspiration: Walnut Way, Milwaukee, WI 10 Chapter 3: Parts of a Fruit Tree 13 Blossoms and Fruit 13 Buds and Leaves 16 Roots 18 Trunk and Bark 20 The Grafted Tree 22 Understanding Grafting: The Story of the McIntosh Apple 23 GROWING URBAN ORCHARDS Part 2: Selecting, Planting and Caring for Your Tree Chapter 4: Selecting Your Fruit Trees 25 Hardiness 26 Disease Resistance 26 Tree Size 27 Cross-Pollinating Fruit Trees 27 Self-Pollinating Fruit Trees 27 Staggering the Harvest 28 Eating, Cooking or Canning 28 Heirloom Trees 28 Orchard Inspiration: Community Orchard Research Project, Calgary, AB. -

Institutional Politics, Power Constellations, and Urban Social Sustainability: a Comparative-Historical Analysis Jason M

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2014 Institutional Politics, Power Constellations, and Urban Social Sustainability: A Comparative-Historical Analysis Jason M. Laguna Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PUBLIC POLICY INSTITUTIONAL POLITICS, POWER CONSTELLATIONS, AND URBAN SOCIAL SUSTAINABILITY: A COMPARATIVE-HISTORICAL ANALYSIS By JASON M. LAGUNA A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2014 Jason M. Laguna defended this dissertation on May 30, 2014. The members of the supervisory committee were: Douglas Schrock Professor Directing Dissertation Andy Opel University Representative Jill Quadagno Committee Member Daniel Tope Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii This is dedicated to all the friends, family members, and colleagues whose help and support made this possible. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ................................................................................................................................. vi Abstract ....................................................................................................................................... -

Producing Edible Landscapes in Seattle's Urban Forest Rebecca J

Ursinus College Digital Commons @ Ursinus College Environmental Studies Faculty Publications Environmental Studies Department 2012 Producing Edible Landscapes in Seattle's Urban Forest Rebecca J. McLain Portland State University Melissa R. Poe Northwest Sustainability Institute Patrick T. Hurley Ursinus College, [email protected] Joyce LeCompte University of Washington Marla R. Emery USDA Forest Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/environment_fac Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Food Security Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other Political Science Commons, Place and Environment Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits oy u. Recommended Citation McLain, Rebecca J.; Poe, Melissa R.; Hurley, Patrick T.; LeCompte, Joyce; and Emery, Marla R., "Producing Edible Landscapes in Seattle's Urban Forest" (2012). Environmental Studies Faculty Publications. 7. https://digitalcommons.ursinus.edu/environment_fac/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Environmental Studies Department at Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Environmental Studies Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Ursinus College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 11 (2012) 187–194 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect -

Locally Sourcedsourced

InsideAgroforestryVOLUME 22 ISSUE 2 LocallyLocally SourcedSourced When we think about agroforestry, the production side of agroforestry – the trees, crops, and livestock that make up agroforestry systems – Inside is often what we think of first, not the economics or products. Plant a Many publications address the ecology The articles in this newsletter aren’t meant Tree of Life and management of agroforestry systems or to be comprehensive. There are many 4 their ecological benefits. Others focus on agroforestry systems not mentioned here the ecological benefits of these agroforestry that produce important food products, like FOOD HUB FACTS Food hubs manage the aggregation, practices, such as improved water, soils, meat from silvopasture systems and grain distribution and marketing of source-identified products primarily from local and regional = 5 producers producers to strengthen their ability to satisfy and wildlife habitat. Food sometimes gets from fields protected by windbreaks. Instead, wholesale, retail, and institutional demand. overlooked, even though its production is this newsletter tries to get us thinking about often a primary driver for landowners. emerging agroforestry markets and systems. Median number of producers The Emerging Role or suppliers per food hub This newsletter seeks to highlight the It addresses agroforestry in places where of Food Hubs 6 62% of food hubs FOOD HUB surveyed began foods that agroforestry producers grow. It we don’t traditionally think of them, like operations within also addresses how agroforestry producers backyards, and discusses new species that the last 5 years 62% Customers are usually within fit into food systems at different scales. can be grown in more traditional agroforestry 400 miles of the food hub In addition to being a component of the systems, like hazelnuts in windbreaks.