The Political History of Canada Between 1840 and 1855

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sir Leonard Tilley

SIR LEONARD TILLEY JAMES HA NNAY TORONTO MORANG CO L IMITE D 1911 CONTENTS EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER ELECTED T0 THE LEGISLAT' RE CHAPTER III THE PROHIBITORY LI' ' OR LAW 29 CHAPTER VI THE MOVEMENT FOR MARITIME ' NION CONTENTS DEFEAT OF CONFEDERATION CHAPTER I' TILLEY AGAIN IN POWER CHAPTER ' THE BRITISH NORTH AMERICA ACT CHA PTER ' I THE FIRST PARLIAMENT OF CANADA CHAPTER ' II FINANCE MINISTER AND GO VERNOR INDE' CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE AND B' SINESS CAREER HE po lit ic al c aree r of Samuel Leonard Tilley did not begin until the year t hat bro ught the work of L emuel Allan Wilmot as a legislator to a we e elect ed e bers t he close . Both r m m of House of 1 850 t he l ea Assembly in , but in fol owing y r Wil elev t ed t o t he benc h t h t t he mot was a , so a province lost his services as a political refo rmer just as a new t o re t man, who was destined win as g a a reputation t he . as himself, was stepping on stage Samuel l at t he . Leonard Til ey was born Gagetown , on St 8th 1 8 1 8 i -five John River, on May , , just th rty years after the landing of his royalist grandfather at St. - l t . e John He passed away seventy eight years a r, ull t he f of years and honours , having won highest prizes that it was in the power of his native province t o bestow. -

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI STRUGGLING WITH DIVERSITY: The Sta[e Education nf the P!ura!Sctic. Upper Canadian Population. 179 1 - 18-11 Robin Bredin A thesis submitted in conformity with the reguirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theory and Policy Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto @Copyright by Robin Bredin. 1000 Natbnaf Library Bibliothèque nationale I*m of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaON KIAON4 OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada Ywr tih Vorm ruhirsncs Our JI&Mire re~~ The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowùig the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in rnicroform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de rnicrofiche/fïh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique . The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in ths thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. -

Canada and Its Provinces in Twenty-Two Volumes and Index

::;:i:;!U*-;„2: UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES (SDi'nbutgf) (ZBDition CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES IN TWENTY-TWO VOLUMES AND INDEX VOLUME X THE DOMINION INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION PART II The Edinburgh Edition of ' Caxada and its Provinces' is limited to Sjs Impressions on All- Rag Watermarked Paper This Impression is Nuviber /.iP..t> LORD STRATHCONA AND MOUNT ROYAL From a photograph by Lafayette CANADA AND ITS PROVINCES A HISTORY OF THE CANADIAN PEOPLE AND THEIR INSTITUTIONS BY ONE HUNDRED ASSOCIATES GENERAL EDITORS: ADAM SHORTT AND ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY VOLUME X THE DOMINION INDUSTRIAL EXPANSION EDINBURGH EDITION PRINTED BY T. ds" A. CONSTABLE AT THE EDINBURGH UNIVERSITY PRESS EOR THE PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION OF CANADA LIMITED TORONTO 1914 . t ( * * " Copyright in all countries subscribing to the Berne Convention — F V. I O CONTENTS rAOK NATIONAL HIGHWAYS OVERLAND. By S. J. MLean I. EARLY GENERAL HISTORY ...... 359 Highways and Highway Travel— Beginnings of Railways n. THE MARITIME PROVINCES ..... 378 The Halifax and Quebec Project—The European and North American Project in. THE CANADAS ....... 39I Railway Policy of Francis Hincks—Railway Expansion in the Canadas IV. CONFEDERATION AND RAILWAY EXPANSION . -417 The Intercolonial—The Canadian Pacific—Railway Develop- ment in Ontario —Quebec Railway Projects— Rate Wars The Gauge Problem V. THE GOVERNMENT AND THE RAILWAYS .... 432 Eastern Expansion of the Canadian Pacific — The Grand Trunk "'. the Canadian Pacific— Manitoba and the Canadian Pacific—The Dominion and the Provinces—The Dominion Subsidy Policy VL RECENT RAILWAY DEVELOPMENT. .... 449 The Influence of 'Wheat'— British Columbia and the Yukon —The Canadian Northern—The Grand Trunk Pacific—The Great Northern in Canada—Government Railways—Govern- ment Aid— Railway Rates—The Board of Railway Com- missioners SHIPPING AND CANALS. -

Biographical Appendix

Biographical Appendix The following women are mentioned in the text and notes. Abney- Hastings, Flora. 1854–1887. Daughter of 1st Baron Donington and Edith Rawdon- Hastings, Countess of Loudon. Married Henry FitzAlan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk, 1877. Acheson, Theodosia. 1882–1977. Daughter of 4th Earl of Gosford and Louisa Montagu (daughter of 7th Duke of Manchester and Luise von Alten). Married Hon. Alexander Cadogan, son of 5th Earl of Cadogan, 1912. Her scrapbook of country house visits is in the British Library, Add. 75295. Alten, Luise von. 1832–1911. Daughter of Karl von Alten. Married William Montagu, 7th Duke of Manchester, 1852. Secondly, married Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, 1892. Grandmother of Alexandra, Mary, and Theodosia Acheson. Annesley, Katherine. c. 1700–1736. Daughter of 3rd Earl of Anglesey and Catherine Darnley (illegitimate daughter of James II and Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester). Married William Phipps, 1718. Apsley, Isabella. Daughter of Sir Allen Apsley. Married Sir William Wentworth in the late seventeenth century. Arbuthnot, Caroline. b. c. 1802. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. She did not marry. Arbuthnot, Marcia. 1804–1878. Daughter of Rt. Hon. Charles Arbuthnot. Stepdaughter of Harriet Fane. Married William Cholmondeley, 3rd Marquess of Cholmondeley, 1825. Aston, Barbara. 1744–1786. Daughter and co- heir of 5th Lord Faston of Forfar. Married Hon. Henry Clifford, son of 3rd Baron Clifford of Chudleigh, 1762. Bannister, Henrietta. d. 1796. Daughter of John Bannister. She married Rev. Hon. Brownlow North, son of 1st Earl of Guilford, 1771. Bassett, Anne. Daughter of Sir John Bassett and Honor Grenville. -

GEORGE BROWN the Reformer

GEORGE BROWN The Reformer by Alastair C.F. Gillespie With a Foreword by the Hon. Preston Manning Board of Directors Richard Fadden Former National Security Advisor to the Prime Minister and former Deputy Minister of National Defence CHAIR Rob Wildeboer Brian Flemming Executive Chairman, Martinrea International Inc. International lawyer, writer, and policy advisor Robert Fulford VICE CHAIR Former Editor of Saturday Night magazine, columnist with Jacquelyn Thayer Scott the National Post Past President and Professor, Wayne Gudbranson Cape Breton University, Sydney CEO, Branham Group Inc., Ottawa MANAGING DIRECTOR Stanley Hartt Brian Lee Crowley Counsel, Norton Rose LLP SECRETARY Calvin Helin Lincoln Caylor International speaker, best-selling author, entrepreneur Partner, Bennett Jones LLP, Toronto and lawyer. TREASURER Peter John Nicholson Martin MacKinnon Former President, Canadian Council of Academies, Ottawa CFO, Black Bull Resources Inc., Halifax Hon. Jim Peterson Former federal cabinet minister, Counsel at Fasken DIRECTORS Martineau, Toronto Pierre Casgrain Maurice B. Tobin Director and Corporate Secretary of Casgrain the Tobin Foundation, Washington DC & Company Limited Erin Chutter President and CEO of Global Cobalt Corporation Research Advisory Board Laura Jones Janet Ajzenstat Executive Vice-President of the Canadian Federation Professor Emeritus of Politics, McMaster University of Independent Business (CFIB). Brian Ferguson Vaughn MacLellan Professor, Health Care Economics, University of Guelph DLA Piper (Canada) LLP Jack Granatstein Historian and former head of the Canadian War Museum Advisory Council Patrick James Professor, University of Southern California John Beck Rainer Knopff Chairman and CEO, Aecon Construction Ltd., Toronto Professor of Politics, University of Calgary Navjeet (Bob) Dhillon Larry Martin President and CEO, Mainstreet Equity Corp., Calgary Principal, Dr. -

Public Lummy

ex n 01 18 A CYCLOPEDIA OF Before Them," " Matrimonial Speculation," law. He represented Norfolk in the Par- and other works of a more or less fictitious liament of Upper Canada, and about six character. It may be said here that after months before his death, which occurred on eight years of travail in the woods, Mrs. the 8th of January, 1844, he was called to Moodie received the glad tidings that her the Legislative Council. Robert, the sub- husband had been appointed Sheriff of the ject of this sketch, entered the practice of County of Hastings. In a late edition of law in 1825, in the well known firm of Bald- " Roughing it in the Bnsh," brought out by win & Son, continuing this calling through Messrs. Hunter, Rose & Co., Publishers, his political career till 3848, when he re- Toronto, Mrs. Moodie writes a preface re- tired. He made his entry into public lif e by counting the social, industrial, educational being elected as the Liberal candidate for and moral progress of Canada, since the the Upper Canada Assembly in 1829, in op- time of her landing. After Mr. Moodie's position to Mr. Smsll, the henchman of the death at Belleville, in 1869, Mrs. Moodie Family Compact. The whole influence of made her home in Toronto with her younger the placemen was used against Mr. Bald- j aon, Mr. R. B. Moodie ; but on his removal win, and William Lyon Mackenzie, who,;:, -with all Ms rashness and roughness, was to a new residence out of towa, Mrs. Moo- 1 die remained with her daughter, Mrs. -

Oleegy Reserve

THE CL E GY E E VE S IN R R S R CANADA. WH E N the Province of C anada was conquered by British ut a tur a o u the forces abo cen y g , its pop lation ' was us e c n ul excl ively Fr n h , and its religio f ly esta li h d h b s e under t e Roman Catholic form . They possessed ample endowments for the main tenance bo of and u o th religion ed cati n ; and, in accordance wi u an th the r les of Establishment, tithes were f and are hi b en orced, they to t s day paid y members of that communionin Lower Canada; fte c n u st ’ e r du A r the o q e , th re was g a ally an intro 'duction of settlers of British origin ; and at the — conclusionof the revolutionary war which terminated ' in the e n n t he aes r ind p e de ce of United St t of Ame ica, u . w en' the loyalists who abandoned that co ntry ere_ ' ' c oi l raged to settle in the more we sterly portions of t he o In 1 1 u v . 79 c nq ered pro ince the year , it was ‘ considered expedient to divide , the province into L and r a a c o u ower Uppe C n da, as their respe tive p p l ations h ad o u u bec me so diverse in lang age , c stoms , “ I n m t u conse and creed . -

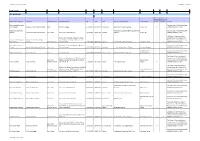

ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Name (As On

Houses of Parliament War Memorials Royal Gallery, First World War ROYAL GALLERY FIRST WORLD WAR Also in Also in Westmins Commons Name (as on memorial) Full Name MP/Peer/Son of... Constituency/Title Birth Death Rank Regiment/Squadron/Ship Place of Death ter Hall Chamber Sources Shelley Leopold Laurence House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Baron Abinger Shelley Leopold Laurence Scarlett Peer 5th Baron Abinger 01/04/1872 23/05/1917 Commander Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve London, UK X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Humphrey James Arden 5th Battalion, London Regiment (London Rifle House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Adderley Humphrey James Arden Adderley Son of Peer 3rd son of 2nd Baron Norton 16/10/1882 17/06/1917 Rifleman Brigade) Lincoln, UK MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) The House of Commons Book of Bodmin 1906, St Austell 1908-1915 / Eldest Remembrance 1914-1918 (1931); Thomas Charles Reginald Thomas Charles Reginald Agar- son of Thomas Charles Agar-Robartes, 6th House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Agar-Robartes Robartes MP / Son of Peer Viscount Clifden 22/05/1880 30/09/1915 Captain 1st Battalion, Coldstream Guards Lapugnoy, France X X MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Horace Michael Hynman Only son of 1st Viscount Allenby of Meggido House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Allenby Horace Michael Hynman Allenby Son of Peer and of Felixstowe 11/01/1898 29/07/1917 Lieutenant 'T' Battery, Royal Horse Artillery Oosthoek, Belgium MCMXIV-MCMXIX (c.1927) Aeroplane over House of Lords, In Piam Memoriam, Francis Earl Annesley Francis Annesley Peer 6th Earl Annesley 25/02/1884 05/11/1914 -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

William Lyon Mackenzie: Led the Reform Movement in Upper Canada

The Road to Confederation 1840 - 1867 William Lyon Mackenzie: Led the reform movement in Upper Canada Despised the ruling oligarchy/ Family Compact Published articles in the Colonial Advocate criticizing the government Wanted American Style democracy 1812 Elected to the Legislative Assembly List of Grievances in Upper Canada Land - overpriced, good land gone, Family Compact dominated land ownership, crown and clergy reserve land blocked road construction Roads - wanted more roads and better quality roads Government - oligarchy controls the government, Governor and 2 councils have all control, Legislative Assembly powerless Controlling Opposition through Violence and Intimidation Robert Gourley drew up the list of grievances and petitioned the government to change he was arrested and deported out of the colony William Lyon Mackenzie’s newspaper Burned office and printing press Problems seem worse in Lower Canada The French population felt culturally attacked Why: the ruling class was English BUT the majority of people were French French population feared the loss of their: Language Religion Culture Power In Lower Canada English Speaking Minority held all the power in Lower Canada Those who control the money control the politics and policies ¼ of the population in control Just like today 1% of the population controls the world Fearing Your Authority French thought the British were going to phase out the “French Problem” Britain encouraged English settlement Encouraged assimilation to British culture Reform Movement In Lower Canada Main Grievances -

Cavendish Square

DRAFT CHAPTER 7 Cavendish Square Peering over the railings and through the black trees into the garden of the Square, you see a few miserable governesses with wan-faced pupils wandering round and round it, and round the dreary grass-plot in the centre of which rises the statue of Lord Gaunt, who fought at Minden, in a three- tailed wig, and otherwise habited like a Roman Emperor. Gaunt House occupies nearly a side of the Square. The remaining three sides are composed of mansions that have passed away into dowagerism; – tall, dark houses, with window-frames of stone, or picked out of a lighter red. Little light seems to be behind those lean, comfortless casements now: and hospitality to have passed away from those doors as much as the laced lacqueys and link-boys of old times, who used to put out their torches in the blank iron extinguishers that still flank the lamps over the steps. Brass plates have penetrated into the square – Doctors, the Diddlesex Bank Western Branch – the English and European Reunion, &c. – it has a dreary look. Thackeray made little attempt to disguise Cavendish Square in Vanity Fair (1847–8). Dreariness could not be further from what had been intended by those who, more than a century earlier, had conceived the square as an enclave of private palaces and patrician grandeur. Nor, another century and more after Thackeray, is it likely to come to mind in what, braced between department stores and doctors’ consulting rooms, has become an oasis of smart offices, sleek subterranean parking and occasional lunch-hour sunbathing. -

Understanding Canadian Bicameralism: Past, Present and Future

1 Understanding Canadian Bicameralism: Past, Present and Future Presented at the 2018 Annual Conference of the Canadian Political Science Association Gary William O’Brien, Ph.D. June, 2018 Not be cited until a final version is uploaded 2 Studies of the Senate of Canada’s institutional design as well as the proposals for its reform have often focused on the method of selection, distribution of seats and powers.1 Another methodology is the use of classification models of bicameral second chambers which also explore power and representation dimensions but in a broader constitutional and political context. Although such models have been employed to study Canada’s upper house in a comparative way,2 they have not been used extensively to understand the origins of the Senate’s underlying structure or to analyze reform proposals for their impact on its present multi-purposed roles. This paper proposes to give a brief description of the models which characterize pre- and post-Confederation second chambers. Given that many of the legal and procedural provisions concerning Canada’s current upper house can be traced back to the Constitutional Act, 1791 and the Act of Union, 1840, it will place Canadian bicameralism within its historical context. The Senate’s “architecture”, “essential characteristics” and “fundamental nature”, terms used in the 1980 and 2014 Supreme Court opinions but with no link to pre- Confederation antecedents, cannot be understood without references to Canadian parliamentary history. Finally, it will provide some observations on the nature of Canadian bicameralism and will conceptualize various reform proposals in terms of classification models.