Systematic Studies of the Costa Rican Moss Salamanders, Genus Nototriton, with Descriptions of Three New Species

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Distritos Declarados Zona Catastrada.Xlsx

Distritos de Zona Catastrada "zona 1" 1-San José 2-Alajuela3-Cartago 4-Heredia 5-Guanacaste 6-Puntarenas 7-Limón 104-PURISCAL 202-SAN RAMON 301-Cartago 304-Jiménez 401-Heredia 405-San Rafael 501-Liberia 508-Tilarán 601-Puntarenas 705- Matina 10409-CHIRES 20212-ZAPOTAL 30101-ORIENTAL 30401-JUAN VIÑAS 40101-HEREDIA 40501-SAN RAFAEL 50104-NACASCOLO 50801-TILARAN 60101-PUNTARENAS 70501-MATINA 10407-DESAMPARADITOS 203-Grecia 30102-OCCIDENTAL 30402-TUCURRIQUE 40102-MERCEDES 40502-SAN JOSECITO 502-Nicoya 50802-QUEBRADA GRANDE 60102-PITAHAYA 703-Siquirres 106-Aserri 20301-GRECIA 30103-CARMEN 30403-PEJIBAYE 40104-ULLOA 40503-SANTIAGO 50202-MANSIÓN 50803-TRONADORA 60103-CHOMES 70302-PACUARITO 10606-MONTERREY 20302-SAN ISIDRO 30104-SAN NICOLÁS 306-Alvarado 402-Barva 40504-ÁNGELES 50203-SAN ANTONIO 50804-SANTA ROSA 60106-MANZANILLO 70307-REVENTAZON 118-Curridabat 20303-SAN JOSE 30105-AGUACALIENTE O SAN FRANCISCO 30601-PACAYAS 40201-BARVA 40505-CONCEPCIÓN 50204-QUEBRADA HONDA 50805-LIBANO 60107-GUACIMAL 704-Talamanca 11803-SANCHEZ 20304-SAN ROQUE 30106-GUADALUPE O ARENILLA 30602-CERVANTES 40202-SAN PEDRO 406-San Isidro 50205-SÁMARA 50806-TIERRAS MORENAS 60108-BARRANCA 70401-BRATSI 11801-CURRIDABAT 20305-TACARES 30107-CORRALILLO 30603-CAPELLADES 40203-SAN PABLO 40601-SAN ISIDRO 50207-BELÉN DE NOSARITA 50807-ARENAL 60109-MONTE VERDE 70404-TELIRE 107-Mora 20307-PUENTE DE PIEDRA 30108-TIERRA BLANCA 305-TURRIALBA 40204-SAN ROQUE 40602-SAN JOSÉ 503-Santa Cruz 509-Nandayure 60112-CHACARITA 10704-PIEDRAS NEGRAS 20308-BOLIVAR 30109-DULCE NOMBRE 30512-CHIRRIPO -

Mapa De Valores De Terrenos Por Zonas Homogéneas Provincia 4

MAPA DE VALORES DE TERRENOS POR ZONAS HOMOGÉNEAS PROVINCIA 4 HEREDIA CANTÓN 03 SANTO DOMINGO 488200 491200 494200 497200 Mapa de Valores de Terrenos Centro Urbano de Santo Domingo por Zonas Homogéneas ESCALA 1:5.000 490200 Barva n Provincia 4 Heredia Avenida 9 CALLE RONDA 2 C RESIDENCIAL VEREDA REAL a SAN VICENTE URBANIZACION LA COLONIA l l Cantón 03 Santo Domingo 4 03 06 U01 4 03 02 U11 e 4 03 02 U06 CALLE RONDA 3 Exofisa LA BASILICA La Casa de los Precios Bajos 4 03 01 U03 4 03 02 U10 Grupo A.A de an l r 1107400 G 1107400 C a ra n a a P a l ío Repuestos Yosomi l Av e C Bar Las Juntas R enida 5 L a San Rafael F o r r a CRUZ ROJA Restaurante El Primero d Qu i n s eb ra s d c a a G I 4 03 01 U02 j u Av ac e La Cruz Roja enida 5 a al Parqueo Plaza Nueva n San Isidro s Ministerio de Hacienda L a a o S i Ave Banco Popular R nida 3 A Abastecedor El Trébol Órgano de Normalización Técnica Tienda Anais os Biblioteca Municipal 9 r Robledales Country House Basílica Santo Domingo de Guzmán lle e a l b Estación de Bomberos G l a a C le C l Plaza de Fútbol de Santo Domingo Ca 4 03 04 R03/U03 o Coope Pará l A l venida 1 i Oficina Parroquial r PlazaIglesia Católica de San Luis r G G a o C Escuela San Luis Gonzaga La Curacao t a s 04 o 5 i ñ a n o t Ru l a g Escuela Félix Arcadio Montero u 4 03 08 R01/U01 p a A r s n CALLE 9 e COMERCIAL E B Municipio d l A 3 veni 4 03 05 U01 a da Ce B.C.R ntral 4 03 01 U01 4 C n ristób e a l l Coló o n l 5 LA BASILICA i Salón Parroquial a c SANTA ROSA URBANO e C a l l 4 03 01 U04 Zapatería Santa Rosa G N 4 03 06 R03/U03 a 4 03 08 R02/U02 PARÁ a C r Iglesia El Rosario CONDOMINIO LOS HIDALGOS e t G e R 4 03 05 U02 r r í SANTO DOMINGO o a A Centro Educativo Santa María C Avenida 2 Condominio La Domingueña er g n Del Co et r m a Depósito San Carlos ercio lle P K-9 Ca Cementerio de San Luis R Banco Nacional u t a 3 C Industrias Zurquí 0 a 8 l l e E ZONA JUZGADO Y CORREO a m r Aprobado por: a 1103400 1103400 4 03 01 U05 i PARACITO l P i a o í SANTA ROSA 4 03 07 R06/U06 R s SANTO TOMÁS á b 6 i da T l i 6 x n Av ve e i nida A Calle La Canoa Ing. -

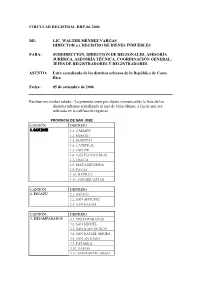

Circular Registral Drp-06-2006

CIRCULAR REGISTRAL DRP-06-2006 DE: LIC. WALTER MÉNDEZ VARGAS DIRECTOR a.i. REGISTRO DE BIENES INMUEBLES PARA: SUBDIRECCIÓN, DIRECCIÓN DE REGIONALES, ASESORÍA JURÍDICA, ASEOSRÍA TÉCNICA, COORDINACIÓN GENERAL, JEFES DE REGISTRADORES Y REGISTRADORES. ASUNTO: Lista actualizada de los distritos urbanos de la República de Costa Rica Fecha: 05 de setiembre de 2006 Reciban mi cordial saludo. La presente tiene por objeto comunicarles la lista de los distritos urbanos actualizada al mes de Julio último, a fin de que sea utilizada en la califiación registral. PROVINCIA DE SAN JOSE CANTÓN DISTRITO 1. SAN JOSE 1.1. CARMEN 1.2. MERCED 1.3. HOSPITAL 1.4. CATEDRAL 1.5. ZAPOTE 1.6. SAN FCO DOS RIOS 1.7. URUCA 1.8. MATA REDONDA 1.9. PAVAS 1.10. HATILLO 1.11. SAN SEBASTIAN CANTÓN DISTRITO 2. ESCAZU 2.1. ESCAZU 2.2. SAN ANTONIO 2.3. SAN RAFAEL CANTÓN DISTRITO 3. DESAMPARADOS 3.1. DESAMPARADOS 3.2. SAN MIGUEL 3.3. SAN JUAN DE DIOS 3.4. SAN RAFAEL ARRIBA 3.5. SAN ANTONIO 3.7. PATARRA 3.10. DAMAS 3.11. SAN RAFAEL ABAJO 3.12. GRAVILIAS CANTÓN DISTRITO 4. PURISCAL 4.1. SANTIAGO CANTÓN DISTRITO 5. TARRAZU 5.1. SAN MARCOS CANTÓN DISTRITO 6. ASERRI 6.1. ASERRI 6.2. TARBACA (PRAGA) 6.3. VUELTA JORCO 6.4. SAN GABRIEL 6.5.LEGUA 6.6. MONTERREY CANTÓN DISTRITO 7. MORA 7.1 COLON CANTÓN DISTRITO 8. GOICOECHEA 8.1.GUADALUPE 8.2. SAN FRANCISCO 8.3. CALLE BLANCOS 8.4. MATA PLATANO 8.5. IPIS 8.6. RANCHO REDONDO CANTÓN DISTRITO 9. -

Casos COVID-19 En La Provincia De Heredia Datos

Casos COVID-19 en la provincia de Heredia Datos: Ministerio de Salud 02-07-2020 Provincia Casos Casos Casos Activos Fallecidos Acumulados Recuperados Heredia 415 141 273 1 Casos COVID-19 por Distrito Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados Heredia 205 58 146 Heredia 51 20 31 Mercedes 46 17 29 San Francisco 89 15 73 *Se registra 1 persona fallecida (extranjera de 48 años que residía en este distrito) Ulloa 18 5 13 Vara Blanca 0 0 0 Sin información de 1 1 0 distrito Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados Barva 34 12 22 Barva 6 5 1 San José de la 0 0 0 Montaña San Pablo 4 2 2 San Pedro 18 2 16 San Roque 4 2 2 Santa Lucía 2 1 1 Más noticias en www.velero.cr Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados Belén 32 12 20 La Asunción 1 0 1 La Ribera 23 5 18 San Antonio 8 7 1 Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados Flores 12 2 10 Barrantes 3 1 2 Llorente 3 1 2 San Joaquín 6 0 6 Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados San Isidro 12 1 11 Concepción 0 0 0 San Francisco 2 0 2 San Isidro 9 1 8 San José 1 0 1 Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados San Pablo 32 17 15 Rincón de 5 2 3 Sabanilla San Pablo 27 15 12 Más noticias en www.velero.cr Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados San Rafael 33 17 16 Ángeles 6 6 0 Concepción 4 3 1 San Josecito 7 2 5 San Rafael 14 5 9 Santiago 1 1 0 Sin información de 1 0 1 distrito Cantón Distrito Casos Casos Casos Activos Acumulados Recuperados Santa -

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre

Provincia Nombre Provincia Cantón Nombre Cantón Distrito Nombre Distrito Barrio Nombre Barrio 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 1 Amón 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 2 Aranjuez 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 3 California (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 4 Carmen 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 5 Empalme 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 6 Escalante 1 San José 1 San José 1 CARMEN 7 Otoya. 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 1 Bajos de la Unión 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 2 Claret 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 3 Cocacola 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 4 Iglesias Flores 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 5 Mantica 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 6 México 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 7 Paso de la Vaca 1 San José 1 San José 2 MERCED 8 Pitahaya. 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 1 Almendares 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 2 Ángeles 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 3 Bolívar 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 4 Carit 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 5 Colón (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 6 Corazón de Jesús 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 7 Cristo Rey 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 8 Cuba 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 9 Dolorosa (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 10 Merced 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 11 Pacífico (parte) 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 12 Pinos 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 13 Salubridad 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 14 San Bosco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 15 San Francisco 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 16 Santa Lucía 1 San José 1 San José 3 HOSPITAL 17 Silos. -

(Tortricidae) of Costa Rica, with Summaries of Their Spatial and Temporal Distribution

JOURNAL OF THE LEPIDOPTERISTS' SOCIETY Volume ,57 2003 Number 4 Journal of the Lepidopterists' SOciety 57(4) , 200:3,253- 269 AN ILLUSTRATED GUIDE TO THE ORTHOCOMOTIS DOGNIN (TORTRICIDAE) OF COSTA RICA, WITH SUMMARIES OF THEIR SPATIAL AND TEMPORAL DISTRIBUTION JOHN W. BROWN Systematic Entomology LaboratOlY, Plant Sciences lnstitute, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, c/o N alional M uscum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20560-0168, USA. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Ten species of Orthocomotis Dognin are reported from Costa Rica: 0. ochmcea Clarke; 0.. herbacea Clarke (~o. subolivata Clarke. new synonymy); O. langicilia Brown, new species; o.. magicana (Zeller); o.. ettaldem (Druce); 0. herbaria (Busck) ( ~ o.. cristata Clarke, new synonymy; ~ o.. uragia Razowski & Becker, new synonymy); 0. phenax Razowski & Becker; O. similis Brown, new species; o.. nitida Clarke; and O. altivalans Brown, new species. o.rtttocomotis herbacea has been reared hom avocado (Persea americana) and 0. herbaria from Nectandra hihua, both in the Lauraceae, suggesting that this plant family may act as the larval host for other species of o.rthoco motis. A portion of a preserved pupal exuvium associated with the bolotype of 0. herhacea suggcsts that the pupae of o.rthocomotis are typical for Tortricidac, with the abdominal dorsal pits conspicuous in this stage. Adults and gcnitalia of all specics are illustrated, and elevational oc curre!1(;e is graphed. o.rthocouwtis herbaria and 0. nitirla are species of the lowlands (ca. 0-800 m); 0. altivalans is restricted to the highest el evations (ca. 2000-3000 m); the remainder of the species occupy the middle elevations (ca. -

Codigos Geograficos

División del Territorio de Costa Rica Por: Provincia, Cantón y Distrito Según: Código 2007 Código Provincia, Cantón y Distrito COSTA RICA 1 PROVINCIA SAN JOSE 101 CANTON SAN JOSE 10101 Carmen 10102 Merced 10103 Hospital 10104 Catedral 10105 Zapote 10106 San Francisco de Dos Ríos 10107 Uruca 10108 Mata Redonda 10109 Pavas 10110 Hatillo 10111 San Sebastián 102 CANTON ESCAZU 10201 Escazú 10202 San Antonio 10203 San Rafael 103 CANTON DESAMPARADOS 10301 Desamparados 10302 San Miguel 10303 San Juan de Dios 10304 San Rafael Arriba 10305 San Antonio 10306 Frailes 10307 Patarrá 10308 San Cristóbal 10309 Rosario 10310 Damas 10311 San Rafael Abajo 10312 Gravilias 10313 Los Guido 104 CANTON PURISCAL 10401 Santiago 10402 Mercedes Sur 10403 Barbacoas 10404 Grifo Alto 10405 San Rafael 10406 Candelaria 10407 Desamparaditos 10408 San Antonio 10409 Chires 105 CANTON TARRAZU 10501 San Marcos 10502 San Lorenzo 10503 San Carlos 106 CANTON ASERRI 10601 Aserrí 10602 Tarbaca o Praga 10603 Vuelta de Jorco 10604 San Gabriel 10605 La Legua 10606 Monterrey 10607 Salitrillos 107 CANTON MORA 10701 Colón 10702 Guayabo 10703 Tabarcia 10704 Piedras Negras 10705 Picagres 108 CANTON GOICOECHEA 10801 Guadalupe 10802 San Francisco 10803 Calle Blancos 10804 Mata de Plátano 10805 Ipís 10806 Rancho Redondo 10807 Purral 109 CANTON SANTA ANA 10901 Santa Ana 10902 Salitral 10903 Pozos o Concepción 10904 Uruca o San Joaquín 10905 Piedades 10906 Brasil 110 CANTON ALAJUELITA 11001 Alajuelita 11002 San Josecito 11003 San Antonio 11004 Concepción 11005 San Felipe 111 CANTON CORONADO -

2010 Death Register

Costa Rica National Institute of Statistics and Censuses Department of Continuous Statistics Demographic Statistics Unit 2010 Death Register Study Documentation July 28, 2015 Metadata Production Metadata Producer(s) Olga Martha Araya Umaña (OMAU), INEC, Demographic Statistics Unit Coordinator Production Date July 28, 2012 Version Identification CRI-INEC-DEF 2010 Table of Contents Overview............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Scope & Coverage.............................................................................................................................................. 4 Producers & Sponsors.........................................................................................................................................5 Data Collection....................................................................................................................................................5 Data Processing & Appraisal..............................................................................................................................6 Accessibility........................................................................................................................................................ 7 Rights & Disclaimer........................................................................................................................................... 8 Files Description................................................................................................................................................ -

Breeding and Molting Periods in a Population of the Andean Sparrow

BREEDING AND MOLTING PERIODS IN A COSTA RICAN POPULATION OF THE ANDEAN SPARROW LARRY L. WOLF Department of Zoology Syracuse University Syracuse, New York 13210 Photoperiodic changes have been established Heredia to Voldn PO&. The specimens were ob- as an important environmental component tained almost exclusively from pastures, especially controlling breeding cycles in north temperate ones that contained some brush. No attempt was made to sample one area systematically or to sample all birds, but there has been little detailed in- areas. This may have biased the results slightly when vestigation of the factors controlling breeding we initially selected territorial birds and then, since seasons of tropical birds. The lack of much we traversed the same area each time, we later col- experimental examination of the controlling lected the replacement birds. Any floating population of non-breeders early in the season may have been factors in part is explained by the deficiency allowed a place in the breeding population. Later in detailed knowledge of cycles of populations samples conceivably could have been obtained from in the wild and the apparent exogenous cor- a population in which there were birds that initially relates of these cycles. There have been some had been excluded from the breeding population. Often in passerines, non-breeders are first-year birds studies in the Old World tropics (e.g., Baker which, for some species, are somewhat retarded in et al. 1940; Moreau et al. 1947). However, reaching full breeding capacity (Wright and Wright the number of studies from tropical America 1944; Selander and Hauser 1965). However, this prob- is very limited. -

Máxima Vulnerabilidad Humana En Santo Domingo De Heredia

Rev. Reflexiones 94 (1): 37-47, ISSN: 1021-1209 / 2015 MÁXIMA VULNERABILIDAD HUMANA EN SANTO DOMINGO DE HEREDIA MAXIMUM HUMAN VULNERABILITY IN SANTO DOMINGO DE HEREDIA Jonnathan Reyes Cháves* [email protected] Mario Fernández Arce** [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 19 marzo 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 25 setiembre 2014 Resumen El Preventec y la Escuela de Geografía unieron esfuerzos para realizar un análisis global de vulnera- bilidad ante amenazas tanto naturales como antrópicas en el cantón de Santo Domingo de Heredia. Para ello se evaluaron 27 indicadores de vulnerabilidad y se determinaron las áreas más vulnerables del cantón. El trabajo se llevó a cabo porque en Santo Domingo hay amenazas que han causado severo daño a los asentamientos humanos pero nunca se ha hecho una estimación de los elementos vulnerables en dicho cantón. El fin de la investigación es identificar las zonas más vulnerables y guiar los esfuerzos hacia ellas para reducir la susceptibilidad de la población al impacto de las amenazas. Para cumplir la meta, en cada Unidad Geoestadística Mínima (UGM) de Santo Domingo se obtuvo un índice de vul- nerabilidad de valor entre 0 y 1, siendo 1 el máximo valor de vulnerabilidad. Posteriormente, las áreas críticas se graficaron en un mapa. Los resultados sugieren que Santo Domingo es un cantón de baja vulnerabilidad y que las áreas críticas están restringidas a zonas inundables donde los asentamientos humanos tienen gran exposición física y poco recurso económico. Palabras clave: Vulnerabilidad, amenaza, riesgo, desastre, exposición, indicador Abstract Preventec and the Geography school, both of the University of Costa Rica, joined efforts to make a comprehensive analysis of vulnerability to natural and anthropogenic hazards in the canton (county) Santo Domingo de Heredia. -

Diversity of Birds Along an Elevational Gradient in the Cordillera Central, Costa Rica

The Auk 117(3):663-686, 2000 DIVERSITY OF BIRDS ALONG AN ELEVATIONAL GRADIENT IN THE CORDILLERA CENTRAL, COSTA RICA JOHN G. BLAKE• AND BETTEA. LOISELLE Departmentof Biologyand International Center for TropicalEcology, University of Missouri-St.Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63121, USA ABSTRACT.--Speciesdiversity and communitycomposition of birds changerapidly along elevationalgradients in CostaRica. Suchchanges are of interestecologically and illustrate the value of protectingcontinuous gradients of forest.We used mist nets and point counts to samplebirds alongan elevationalgradient on the northeasternCaribbean slope of the Cordillera Central in Costa Rica. Sites included mature tropical wet forest (50 m); tropical wet, cool transition forest (500 m); tropical premontanerain forest (1,000 m); and tropical lower montane rain forest (1,500 and 2,000 m). We recorded 261 speciesfrom 40 families, including 168 speciescaptured in mist nets (7,312 captures)and 226 detectedduring point counts(17,071 observations). The sampleincluded 40 threatenedspecies, 56 elevationalmi- grants,and 22 latitudinalmigrants. Species richness (based on rarefaction analyses) changed little from 50 to 1,000rn but was lower at 1,500 and 2,000 m. Mist nets and point countsoften provided similar views of community structure among sites based on relative importance of differencecategories of species(e.g. migrant status,trophic status). Nonetheless, impor- tant differencesexisted in numbersand typesof speciesrepresented by the two methods. Ninety-threespecies were detectedon point countsonly and 35 were capturedonly. Ten families,including ecologically important ones such as Psittacidae and Cotingidae, were not representedby captures.Elevational migrants and threatenedspecies occurred throughout the gradient,illustrating the needto protectforest at all elevations.A comparablestudy from the Cordillera de Tilaran (Younget al. -

Personas Menores De Edad a La Luz Del Censo 2011

Personas menores de edad a la luz del Censo 2011 Proyecto Sistema de Información Estadística en Derechos de la Niñez y Adolescencia (SIEDNA) San José, Costa Rica MARZO, 2013 Personas menores de edad a la luz del Censo 2011 Se permite la reproducción total o parcial con propósitos educativos y sin fines de lucro, con la condición de que se indique la fuente. Diseño de los cuadros y procesamiento de la información: Proyecto SIEDNA - Universidad de Costa Rica Patricia Delvó Gutiérrez, Coordinadora del Proyecto Sofía Bartels Gómez, Asistente del Proyecto Producción Gráfica: Douglas Rivera Solano Adriana Fernández Gamboa. PERSonas mENoRES DE EDAD CENSo 2011 3 Índice General Página Presentación . 7 Cuadros .sobre .personas .menores .de .edad .según .provincia, .cantón .y .distrito . 8 Cuadros .sobre .personas .menores .de .edad .según .regionalizacion .del . Patronato .Nacional .de .la .Infancia .a .nivel .de .distrito . .210 Anexo .1 . .Ficha .metodológica . .412 Anexo .2 . .Cuadro .sinóptico . .417 Anexo .3 . .Boleta .censal . 418 PERSonas mENoRES DE EDAD CENSo 2011 4 Índice de cuadros sobre personas menores de edad según provincia, cantón y distrito Página Cuadro 1. Costa Rica: Población total y personas menores de edad por sexo, según provincia, cantón y distrito . 9 Cuadro 2. Costa Rica: Población de menores de edad por grupo y sexo, según provincia, cantón y distrito, . 27 Cuadro 3. Costa Rica: Personas menores de edad por grupo de edad y sexo, según provincia, cantón y distrito . 45 Cuadro 4. Costa Rica: Personas menores de edad con al menos una discapacidad por tipo, según provincia, cantón y distrito . 81 Cuadro 5. Costa Rica: Personas menores de edad que asisten por lugar de asistencia y que no asisten, según provincia, cantón y distrito, .