Handel Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Female Soprano Roles in Handel's Operas Simple

Female Soprano Roles in Handel's 39 Operas compiled by Jennifer Peterson, operamission a recommended online source for plot synopses Key Character Singer who originated role # of Arias/Ariosos/Duets/Accompagnati Opera, HWV (Händel-Werke-Verzeichnis) Almira, HWV 1 (1705) Almira unknown 8/1/1/2 Edilia unknown 4/1/1/0 Bellante unknown 2/2/1/1 NOTE: libretto in both German and Italian Rodrigo, HWV 5 (1707) Esilena Anna Maria Cecchi Torri, "La Beccarina" 7/1/1/1 Florinda Aurelia Marcello 5/1/0/0 Agrippina, HWV 6 (1709) Agrippina Margherita Durastanti 8/0/0 (short quartet)/0 Poppea Diamante Maria Scarabelli 9/0/0 (short trio)/0 Rinaldo, HWV 7 (1711) Armida Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 3/1/2/1 Almirena Isabella Girardeau 3/1/1/0 Il Pastor Fido, HWV 8 (1712) Amarilli Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 3/0/1/1 Eurilla Francesca Margherita de l'Épine, "La Margherita" 4/1/0/0 Page 1 of 5 Teseo, HWV 9 (1712) Agilea Francesca Margherita de l'Épine, "La Margherita" 7/0/1/0 Medea – Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 5/1/1/2 Clizia – Maria Gallia 2/0/2/0 Silla, HWV 10 (?1713) Metella unknown 4/0/0/0 Flavia unknown 3/0/2/0 Celia unknown 2/0/0/0 Amadigi di Gaula, HWV 11 (1715) Oriana Anastasia Robinson 6/0/1/0 Melissa Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti, "Pilotti" 5/1/1/0 Radamisto, HWV 12 (1720) Polissena Ann Turner Robinson 4/1/0/0 Muzio Scevola, HWV 13 (1721) Clelia Margherita Durastanti 2/0/1/1 Fidalma Maddalena Salvai 1/0/0/0 Floridante, HWV 14 (1721) Rossane Maddalena Salvai 5/1/1/0 Ottone, HWV 15 (1722) Teofane Francesca -

November 4 November 11

NOVEMBER 4 ISSUE NOVEMBER 11 Orders Due October 7 23 Orders Due October 14 axis.wmg.com 11/1/16 AUDIO & VIDEO RECAP ARTIST TITLE LBL CNF UPC SEL # SRP ORDERS DUE Hope, Bob Bob Hope: Hope for the Holidays (DVD) TL DV 610583538595 31845-X 12.95 9/30/16 Last Update: 09/20/16 For the latest up to date info on this release visit axis.wmg.com. ARTIST: Bob Hope TITLE: Bob Hope: Hope for the Holidays (DVD) Label: TL/Time Life/WEA Config & Selection #: DV 31845 X Street Date: 11/01/16 Order Due Date: 09/30/16 UPC: 610583538595 Box Count: 30 Unit Per Set: 1 SRP: $12.95 Alphabetize Under: H ALBUM FACTS Genre: Television Description: HOPE FOR THE HOLIDAYS... There’s no place like home for the holidays. And there really was no place like Bob Hope’s home for the holidays with Bob, Dolores and the Hope family. They invited friends from the world of entertainment and sports to celebrate and reminisce about vintage seasonal sketches in the 1993 special Bob Hope’s Bag Full of Christmas Memories. Bob Hope’s TV Christmas connection began on December 24, 1950, with The Comedy Hour. Heartwarming and fun—that’s the way Bob planned it. No Christmas party would be complete without music, while flubbed lines in some sketches remain intact and a blooper really hits below the belt. The host of Christmases past hands out laughs galore! HIGHLIGHTS INCLUDE: A compilation of Bob’s monologues from his many holiday tours for the USO Department store Santas Robert Cummings and Bob swap stories on the subway Redd Foxx and Bob play reindeer reluctant to guide Santa’s sleigh -

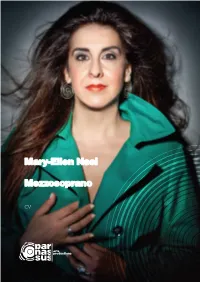

Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano

Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano CV CV PARNASSUS ARTS PRODUCTIONS Mary-Ellen Nesi Mezzosoprano A leading singer worldwide, Greek mezzo-so- prano Mary-Ellen Nesi has appeared at major international venues, including Bayerische Staatsoper, Carnegie Hall, Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Frankfurt Opera, Théâtre de Champs-Elysées, Avery Fisher Hall (NY), Strathmore Hall (Washington DC), Semperop- er (Dresden), Royal Opera of Versailles, Chun- gmu Art Hall (Seoul), Opéra National du Rhin, Theater an der Wien, Place des Arts (Mont- real), Concertgebouw, Opéra de Nice, Opera of Lausanne, Arriaga (Bilbao), Teatro de la Maes- tranza (Seville), Teatro Olimpico (Rome), Sao Carlos Opera (Lisbon), the Operas of Florence, Ferrara, Modena and Piacenza, the Wiesbaden Opera, Caio Melisso (Spoleto), the Baden Baden Festpielhaus. She has also appeared in renowned festivals around the world and she was founder and artistic director of the Opera Festival of Ancient Corinth (2003-2009). Mary-Ellen’s main focus lies in the baroque, classical and belcanto repertoire. She has performed more than 35 title and principal roles in operas by Monteverdi, Handel, Vivaldi, A.Scarlatti, Pergolesi, Porpora, Gluck, Paisiel- lo, Mozart, Rossini, Bizet, Donizetti, Bellini, R.Strauss, Verdi, Humperdinck, Mascagni, Massenet and contemporary composers. She has recorded Handel’s operas Oreste, Arianna in Creta, Tamerlano (ECHO KLASSIK 2008), Giulio Cesare, Alessando Severo, under George Petrou and Gluck’s Il Trionfo di Clelia, under G.Sigismondi (MDG), A.Scarlatti’s Tolo- meo e Alessandro(Archiv), Handel’s Berenice (Virgin) and a solo CD Salve Regina (DHM) under Alan Curtis, Vivaldi’s Il Farnace, under Diego Fasolis (Virgin), Christmas at San Marco under Peter Kopp (Berlin Classics). -

Raffaele Pe, Countertenor La Lira Di Orfeo

p h o t o © N i c o l a D a l M Raffaele Pe, countertenor a s o ( R Raffaella Lupinacci, mezzo-soprano [track 6] i b a l t a L u c e La Lira di Orfeo S t u d i o Luca Giardini, concertmaster ) ba Recorded in Lodi (Teatro alle Vigne), Italy, in November 2017 Engineered by Paolo Guerini Produced by Diego Cantalupi Music editor: Valentina Anzani Executive producer & editorial director: Carlos Céster Editorial assistance: Mark Wiggins, María Díaz Cover photos of Raffaele Pe: © Nicola Dal Maso (RibaltaLuce Studio) Design: Rosa Tendero © 2018 note 1 music gmbh Warm thanks to Paolo Monacchi (Allegorica) for his invaluable contribution to this project. giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero giulio cesare, a baroque hero 5 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo (c165 3- 1723) Sdegnoso turbine 3:02 Opera arias (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , Rome, 1713, I.2; libretto by Antonio Ottoboni) role: Giulio Cesare ba 6 George Frideric Handel Son nata a lagrimar 7:59 (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.12; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) roles: Sesto and Cornelia 1 George Frideric Handel (168 5- 1759) Va tacito e nascosto 6:34 7 Niccolò Piccinni (from Giulio Cesare in Egitto , London, 1724, I.9; libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym) Tergi le belle lagrime 6:36 role: Giulio Cesare (sung in London by Francesco Bernardi, also known as Senesino ) (from Cesare in Egitto , Milan, 1770, I.1; libretto after Giacomo Francesco Bussani) role: Giulio Cesare (sung in Milan by Giuseppe Aprile, also known as Sciroletto ) 2 Francesco Bianchi (175 2- -

Handel Arias

ALICE COOTE THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET HANDEL ARIAS HERCULES·ARIODANTE·ALCINA RADAMISTO·GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL A portrait attributed to Balthasar Denner (1685–1749) 2 CONTENTS TRACK LISTING page 4 ENGLISH page 5 Sung texts and translation page 10 FRANÇAIS page 16 DEUTSCH Seite 20 3 GEORGE FRIDERIC HANDEL (1685–1759) Radamisto HWV12a (1720) 1 Quando mai, spietata sorte Act 2 Scene 1 .................. [3'08] Alcina HWV34 (1735) 2 Mi lusinga il dolce affetto Act 2 Scene 3 .................... [7'45] 3 Verdi prati Act 2 Scene 12 ................................. [4'50] 4 Stà nell’Ircana Act 3 Scene 3 .............................. [6'00] Hercules HWV60 (1745) 5 There in myrtle shades reclined Act 1 Scene 2 ............. [3'55] 6 Cease, ruler of the day, to rise Act 2 Scene 6 ............... [5'35] 7 Where shall I fly? Act 3 Scene 3 ............................ [6'45] Giulio Cesare in Egitto HWV17 (1724) 8 Cara speme, questo core Act 1 Scene 8 .................... [5'55] Ariodante HWV33 (1735) 9 Con l’ali di costanza Act 1 Scene 8 ......................... [5'42] bl Scherza infida! Act 2 Scene 3 ............................. [11'41] bm Dopo notte Act 3 Scene 9 .................................. [7'15] ALICE COOTE mezzo-soprano THE ENGLISH CONCERT HARRY BICKET conductor 4 Radamisto Handel diplomatically dedicated to King George) is an ‘Since the introduction of Italian operas here our men are adaptation, probably by the Royal Academy’s cellist/house grown insensibly more and more effeminate, and whereas poet Nicola Francesco Haym, of Domenico Lalli’s L’amor they used to go from a good comedy warmed by the fire of tirannico, o Zenobia, based in turn on the play L’amour love and a good tragedy fired with the spirit of glory, they sit tyrannique by Georges de Scudéry. -

Jonathan Leif Thomas, Countertenor Dr

The University of North Carolina at Pembroke Department of Music Presents Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan Leif Thomas, countertenor Dr. Seung-Ah Kim, piano Presentation of Research Findings Jonathan Thomas INTERMISSION Dove sei, amato bene? (from Rodelinda).. George Frideric Handel (1685-1759) Ch'io mai vi possa (from Siroe) fl fervido desiderio .Vincenzo Bellini (1801-1835) Ma rendi pur contento Now sleeps the crimson petal.. .. Roger Quilter (1877-1953) Blow, blow, thou winter wind Pie Jesu (from Requiem) .. Andrew Lloyd Webber Dr. Jaeyoon Kim, tenor (b.1948) THESIS COMMITTEE Dr. Valerie Austin Thesis Advisor Dr. Jaeyoon Kim Studio Professor Dr. Jose Rivera Dr. Katie White This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in Music Education. Jonathan Thomas is a graduate student of Dr. Valerie Austin and studies voice with Dr. Jaeyoon Kim. As a courtesy to the performers and audience, please adjust all mobile devices for no sound and no light. Please enter and exit during applause only. March 27,2014 7:30 PM Moore Hall Auditorium This publication is available in alternative formats upon request. Please contact Disability Support Services, OF Lowry Building, 521.6695. Effective Instructional Strategies for Middle School Choral Teachers: Teaching Middle School Boys to Sing During Vocal Transition UNCP Graduate Lecture Recital Jonathan L. Thomas / Abstract Teaching vocal skills to male students whose voices are transitioning is an undertaking that many middle school choral teachers find challenging. Research suggests that one reason why challenges exist is because of teachers' limited knowledge about the transitioning male voice. The development of self-identity, peer pressure, and the understanding of social norms, which will be associated with psychological transitions for this study, is another factor that creates instructional challenges for choral teachers. -

Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel

Six Hundred Forty-Third Program of the 2008-09 Season ____________________ Indiana University Opera Theater presents as its 404th production Giulio Cesare Music by George Frideric Handel Libretto by Nicola Francesco Haym (adapted from G. F. Bussani) Gary Thor Wedow,Conductor Tom Diamond, Stage Director Robert O’Hearn,Costumes and Set Designer Michael Schwandt, Lighting Designer Eiddwen Harrhy, Guest Coach Wendy Gillespie, Elisabeth Wright, Master Classes Paul Elliott, Additional Coachings Michael McGraw, Director, Early Music Institute Chris Faesi, Choreographer Adam Noble, Fight Choreographer Marcello Cormio, Italian Diction Coach Giulio Cesare was first performed in the King’s Theatre of London on Feb. 20, 1724. ____________________ Musical Arts Center Friday Evening, February Twenty-Seventh Saturday Evening, February Twenty-Eighth Friday Evening, March Sixth Saturday Evening, March Seventh Eight O’Clock music.indiana.edu Cast (in order of appearance) Giulio Cesare (Julius Caesar) . Daniel Bubeck, Andrew Rader Curio, a Roman tribune . Daniel Lentz, Antonio Santos Cornelia, widow of Pompeo . Lindsay Ammann, Julia Pefanis Sesto, son to Cornelia and Pompeo . Ann Sauder Archilla, general and counselor to Tolomeo . Adonis Abuyen, Cody Medina Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt . Jacqueline Brecheen, Meghan Dewald Nireno, Cleopatra’s confidant . Lydia Dahling, Clara Nieman Tolomeo, King of Egypt . Dominic Lim, Peter Thoresen Onstage Violinist . Romuald Grimbert-Barre Continuo Group: Harpsichord . Yonit Kosovske Theorbeo, Archlute, and Baroque Guitar . Adam Wead Cello . Alan Ohkubo Supernumeraries . Suna Avci, Joseph Beutel, Curtis Crafton, Serena Eduljee, Jason Jacobs, Christopher Johnson, Kenneth Marks, Alyssa Martin, Meg Musick, Kimberly Redick, Christiaan Smith-Kotlarek, Beverly Thompson 2008-2009 IU OPERA theater SEASON Dedicates this evening’s performance of by George Frideric Handel Giulioto Georgina Joshi andCesare Louise Addicott Synopsis Place: Egypt Time: 48 B.C. -

The Solo Violin in London 1650-1705

‘Florish in the Key’ – the solo violin in London 1650-1705 Played on: Anon – ‘Charles II’ Violin 1664 (tracks 1-34); Girolamo Amati – Violin 1629 (tracks 35-44) (A=416Hz) by Peter Sheppard Skærved Works from ‘Preludes or Voluntarys’ (1705) 1 Arcangelo Corelli D major Prelude 1:10 26 Marc ’Antonio Ziani F minor Prelude 2:21 2 Giuseppe Torelli E minor Prelude 2:53 27 Gottfried Finger E major Prelude 1:25 3 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:37 28 ‘Mr Hills’ A major Prelude 1:40 4 Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber D major Prelude 0:48 29 Johann Christoph Pepusch B flat major Prelude 1:16 5 Giovanni Bononcini D minor Prelude 1:08 30 Giuseppe Torelli C minor Prelude 1:01 6 Nicola Matteis A major Prelude 1:16 31 Nicola Francesco Haym D minor Prelude 1:14 7 Francesco Gasparini D major Prelude 1:31 32 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni C major Prelude 1:19 8 Nicola Francesco Haym F major Prelude 0:50 33 Francesco Gasparini C major Prelude 1:33 9 Johann Gottfried Keller D major Prelude 1:44 34 Nicola Matteis C minor Prelude 2:09 10 ‘Mr Dean’ A major Prelude 2:10 11 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni D major Prelude 1:34 Works from ‘A Set of Tunings by Mr Baltzar’) 12 William Corbett A major Prelude 1:42 35 Thomas Baltzar A major Allemande 1 1:48 13 Henry Eccles A minor Prelude 1:57 36 Thomas Baltzar A major Allemande 2 2:06 14 Arcangelo Corelli A major Prelude 1:23 37 Thomas Baltzar A major ‘Corant.’ 1:21 15 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:26 38 Thomas Baltzar A major ‘Sarabrand.’ 1:30 16 Tomaso Vitali D minor Prelude 1:31 17 John Banister B flat major Prelude 1:12 Other -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XXI, Number 3 Winter 2006 AMERICAN HANDEL SOCIETY- PRELIMINARY SCHEDULE (Paper titles and other details of program to be announced) Thursday, April 19, 2006 Check-in at Nassau Inn, Ten Palmer Square, Princeton, NJ (Check in time 3:00 PM) 6:00 PM Welcome Dinner Reception, Woolworth Center for Musical Studies Covent Garden before 1808, watercolor by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. 8:00 PM Concert: “Rule Britannia”: Richardson Auditorium in Alexander Hall SOME OVERLOOKED REFERENCES TO HANDEL Friday, April 20, 2006 In his book North Country Life in the Eighteenth Morning: Century: The North-East 1700-1750 (London: Oxford University Press, 1952), the historian Edward Hughes 8:45-9:15 AM: Breakfast, Lobby, Taplin Auditorium, quoted from the correspondence of the Ellison family of Hebburn Hall and the Cotesworth family of Gateshead Fine Hall Park1. These two families were based in Newcastle and related through the marriage of Henry Ellison (1699-1775) 9:15-12:00 AM:Paper Session 1, Taplin Auditorium, to Hannah Cotesworth in 1729. The Ellisons were also Fine Hall related to the Liddell family of Ravenscroft Castle near Durham through the marriage of Henry’s father Robert 12:00-1:30 AM: Lunch Break (restaurant list will be Ellison (1665-1726) to Elizabeth Liddell (d. 1750). Music provided) played an important role in all of these families, and since a number of the sons were trained at the Middle Temple and 12:15-1:15: Board Meeting, American Handel Society, other members of the families – including Elizabeth Liddell Prospect House Ellison in her widowhood – lived in London for various lengths of time, there are occasional references to musical Afternoon and Evening: activities in the capital. -

NEWSLETTER of the American Handel Society

NEWSLETTER of The American Handel Society Volume XVI, Number 1 April 2001 HANDEL’S SCIPIONE AND THE NEUTRALIZATION OF POLITICS1 This is an essay about possibilities, an observation of what Handel and his librettist wrote rather than what was finally performed. Handel composed his opera Scipione in 1726 for a text by Paolo Rolli, who adapted a libretto by Antonio Salvi written for a Medici performance in Livorno in 1704.2 Handel’s and Rolli’s version was performed at the King’s Theater in the Haymarket for the Royal Academy of Music.3 The opera has suffered in critical esteem not so much from its own failings as from its proximity in time to the great productions of Giulio Cesare, Tamerlano and Rodelinda which preceeded it. I would like to argue, however, that even in this opera Handel and Rolli were working on an interesting idea: a presentation of Roman historical material in ways that anticipated the ethical discussions that we now associate with the oratorios. If that potential was undermined by what was finally put on stage, it is nevertheless interesting to observe what might have been. Narrative material from the Roman republic was potentially difficult on the English stage of the early eighteenth century. The conquering heroes of the late Roman republic particularly—Sulla, Pompey, and especially Caesar—might most easily be associated with the monarch; but these historical figures were also tainted by the fact that they could be identified as tyrants responsible for demolishing republican freedom. Addison’s Cato had caused a virtual riot in the theatre in 1713, as Whigs and Tories vied to distance themselves from the (unseen) villain Caesar and claim the play’s stoic hero Cato as their own. -

Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques Unearth the Impropriety of the Gods in a Staging of Legrenzi’S La Divisione Del Mondo

Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques unearth the impropriety of the Gods in a staging of Legrenzi’s La Divisione del Mondo 8-16 February 1, 3 March 9 March Strasbourg Mulhouse Colmar 20-27 March Legrenzi La 13, 14 April Nancy Divisione del Mondo Versailles “La Divisione del Mondo shows us a most complicated and modern dysfunctional family - the Roman Gods seem to offer a hilarious mirror of our human misconduct and failures.” - Jetske Mijnssen Christophe Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques tour Giovanni Legrenzi’s rarely-performed La Divisione del Mondo in France from 8 February to 14 April. Directed by Jetske Mijnssen, fifteen performances will be given from Strasbourg to Versailles, via Mulhouse, Colmar, and Nancy, in a co-production with the Opéra national du Rhin and the Opéra national de Lorraine. Seen in its first modern staging in France, the revival of La Divisione del Mondo forms part of Les Talens Lyriques’ season theme, The Temptation of Italy, tracking Italian influences on French writing. Venetian opera had influenced French operatic tradition since its inception, and the only surviving score for La Divisione del Mondo is found in the Bibliothèque nationale de Paris. First performed in a lavish staging with great success at the Venetian Teatro San Salvador in 1675, La Divisione del Mondo depicts the division of the world following the victory of the Olympian gods over the Titan deities: the world inhabited by Madeline Miller’s novel Circe, recently a runaway best-seller in both the New York Times and The Sunday Times. Far from being a banal tale of morals and virtues, instead it unearths dreadful impropriety, with the goddess Venus leading all the other gods (with the exception of Saturn) through a series of moral temptations into debauchery. -

Il Complesso Barocco Edition

Handel: ADMETO (1726) Full score and piano-vocal Vivaldi: ERCOLE SUL TERMODONTE (1723) Full score and piano-vocal ISMN 979-0-2025-3382-6 Alan Curtis’ 1977 performance in Amsterdam‘s Concertgebouw, This important opera, performed in Rome a year earlier than DVD recorded by EMI with René Jacobs singing the title role, has now itself Il Giustino, was long thought to be lost. Nearly all the arias have Stains / Nesi / Cherici / become historical. Curtis has gone over the work and its sources again however been found, some missing their orchestral accompaniments, Dordolo / Bartoli / Scotting / and come up with new conclusions. Although the opera is published in various locations, and the lost recitatives and other missing parts Il Complesso Barocco / complete, he suggests ways to emend, cut, or compensate for the have been composed by Alessandro Ciccolini. Alan Curtis / directed by weaknesses of the outmoded libretto and restore Admeto to the John Pascoe (Spoleto position it deserves, as musically one of Handel’s greatest operas. Festival, 2006) Dynamic (2007) D. Scarlatti: TOLOMEO E ALESSANDRO (1711) Full score and piano-vocal Universally admired for his keyboard music, the vocal music of CD Domenico Scarlatti has until very recently been largely ignored. Hallenberg / Ek / Tolomeo e Alessandro was known only from a manuscript of Act I Invernizzi / Baka / Milanesi / in a private collection in Milan. Recently the entire opera turned up Nesi / Il Complesso Traetta: BUOVO D’ANTONA (1758) Full score and piano-vocal NEW in England and surprisingly revealed that Domenico was after all Barocco / Alan Curtis A charmingly light-hearted libretto by the well-known Venetian CD a very fi ne dramatic composer, perhaps even more appealingly so Universal Music Spain / playwright Carlo Goldoni, was set to music by the as-yet- Trogu-Röhrich / Russo- than his father Alessandro.