Theories for Convection in Stellar Atmospheres

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EVOLUTION of SOLAR FLUX from 0.1 Nm to 160Μm: QUANTITATIVE ESTIMATES for PLANETARY STUDIES

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository The Astrophysical Journal, 757:95 (12pp), 2012 September 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/757/1/95 C 2012. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. THE EVOLUTION OF SOLAR FLUX FROM 0.1 nm TO 160 μm: QUANTITATIVE ESTIMATES FOR PLANETARY STUDIES Mark W. Claire1,2,3, John Sheets2,4, Martin Cohen5, Ignasi Ribas6, Victoria S. Meadows2, and David C. Catling7 1 School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK NR4 7TJ; [email protected] 2 Virtual Planetary Laboratory and Department of Astronomy, University of Washington, Box 351580, Seattle, WA 98195, USA 3 Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, P.O. Box 85561, Seattle, WA 98145-1561, USA 4 Department of Physics & Astronomy, University of Wyoming, Box 204C, Physical Sciences, Laramie, WY 82070, USA 5 Radio Astronomy Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411, USA 6 Institut de Ciencies` de l’Espai (CSIC-IEEC), Facultat de Ciencies,` Torre C5 parell, 2a pl, Campus UAB, E-08193 Bellaterra, Spain 7 Virtual Planetary Laboratory and Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Washington, Box 351310, Seattle, WA 98195, USA Received 2011 December 14; accepted 2012 August 1; published 2012 September 6 ABSTRACT Understanding changes in the solar flux over geologic time is vital for understanding the evolution of planetary atmospheres because it affects atmospheric escape and chemistry, as well as climate. We describe a numerical parameterization for wavelength-dependent changes to the non-attenuated solar flux appropriate for most times and places in the solar system. -

ASTR 545 Module 2 HR Diagram 08.1.1 Spectral Classes: (A) Write out the Spectral Classes from Hottest to Coolest Stars. Broadly

ASTR 545 Module 2 HR Diagram 08.1.1 Spectral Classes: (a) Write out the spectral classes from hottest to coolest stars. Broadly speaking, what are the primary spectral features that define each class? (b) What four macroscopic properties in a stellar atmosphere predominantly govern the relative strengths of features? (c) Briefly provide a qualitative description of the physical interdependence of these quantities (hint, don’t forget about free electrons from ionized atoms). 08.1.3 Luminosity Classes: (a) For an A star, write the spectral+luminosity class for supergiant, bright giant, giant, subgiant, and main sequence star. From the HR diagram, obtain approximate luminosities for each of these A stars. (b) Compute the radius and surface gravity, log g, of each luminosity class assuming M = 3M⊙. (c) Qualitative describe how the Balmer hydrogen lines change in strength and shape with luminosity class in these A stars as a function of surface gravity. 10.1.2 Spectral Classes and Luminosity Classes: (a,b,c,d) (a) What is the single most important physical macroscopic parameter that defines the Spectral Class of a star? Write out the common Spectral Classes of stars in order of increasing value of this parameter. For one of your Spectral Classes, include the subclass (0-9). (b) Broadly speaking, what are the primary spectral features that define each Spectral Class (you are encouraged to make a small table). How/Why (physically) do each of these depend (change with) the primary macroscopic physical parameter? (c) For an A type star, write the Spectral + Luminosity Class notation for supergiant, bright giant, giant, subgiant, main sequence star, and White Dwarf. -

STELLAR SPECTRA A. Basic Line Formation

STELLAR SPECTRA A. Basic Line Formation R.J. Rutten Sterrekundig Instituut Utrecht February 6, 2007 Copyright c 1999 Robert J. Rutten, Sterrekundig Instuut Utrecht, The Netherlands. Copying permitted exclusively for non-commercial educational purposes. Contents Introduction 1 1 Spectral classification (“Annie Cannon”) 3 1.1 Stellar spectra morphology . 3 1.2 Data acquisition and spectral classification . 3 1.3 Introduction to IDL . 4 1.4 Introduction to LaTeX . 4 2 Saha-Boltzmann calibration of the Harvard sequence (“Cecilia Payne”) 7 2.1 Payne’s line strength diagram . 7 2.2 The Boltzmann and Saha laws . 8 2.3 Schadee’s tables for schadeenium . 12 2.4 Saha-Boltzmann populations of schadeenium . 14 2.5 Payne curves for schadeenium . 17 2.6 Discussion . 19 2.7 Saha-Boltzmann populations of hydrogen . 19 2.8 Solar Ca+ K versus Hα: line strength . 21 2.9 Solar Ca+ K versus Hα: temperature sensitivity . 24 2.10 Hot stars versus cool stars . 24 3 Fraunhofer line strengths and the curve of growth (“Marcel Minnaert”) 27 3.1 The Planck law . 27 3.2 Radiation through an isothermal layer . 29 3.3 Spectral lines from a solar reversing layer . 30 3.4 The equivalent width of spectral lines . 33 3.5 The curve of growth . 35 Epilogue 37 References 38 Text available at \tthttp://www.astro.uu.nl/~rutten/education/rjr-material/ssa (or via “Rob Rutten” in Google). Introduction These three exercises concern the appearance and nature of spectral lines in stellar spectra. Stellar spectrometry laid the foundation of astrophysics in the hands of: – Wollaston (1802): first observation of spectral lines in sunlight; – Fraunhofer (1814–1823): rediscovery of spectral lines in sunlight (“Fraunhofer lines”); their first systematic inventory. -

Spectral Classification and HR Diagram of Pre-Main Sequence Stars in NGC 6530

A&A 546, A9 (2012) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201219853 & c ESO 2012 Astrophysics Spectral classification and HR diagram of pre-main sequence stars in NGC 6530,, L. Prisinzano, G. Micela, S. Sciortino, L. Affer, and F. Damiani INAF – Osservatorio Astronomico di Palermo, Piazza del Parlamento, Italy 1, 90134 Palermo, Italy e-mail: [email protected] Received 20 June 2012 / Accepted 3 August 2012 ABSTRACT Context. Mechanisms involved in the star formation process and in particular the duration of the different phases of the cloud contrac- tion are not yet fully understood. Photometric data alone suggest that objects coexist in the young cluster NGC 6530 with ages from ∼1 Myr up to 10 Myr. Aims. We want to derive accurate stellar parameters and, in particular, stellar ages to be able to constrain a possible age spread in the star-forming region NGC 6530. Methods. We used low-resolution spectra taken with VLT/VIMOS and literature spectra of standard stars to derive spectral types of a subsample of 94 candidate members of this cluster. Results. We assign spectral types to 86 of the 88 confirmed cluster members and derive individual reddenings. Our data are better fitted by the anomalous reddening law with RV = 5. We confirm the presence of strong differential reddening in this region. We derive fundamental stellar parameters, such as effective temperatures, photospheric colors, luminosities, masses, and ages for 78 members, while for the remaining 8 YSOs we cannot determine the interstellar absorption, since they are likely accretors, and their V − I colors are bluer than their intrinsic colors. -

The Sun's Dynamic Atmosphere

Lecture 16 The Sun’s Dynamic Atmosphere Jiong Qiu, MSU Physics Department Guiding Questions 1. What is the temperature and density structure of the Sun’s atmosphere? Does the atmosphere cool off farther away from the Sun’s center? 2. What intrinsic properties of the Sun are reflected in the photospheric observations of limb darkening and granulation? 3. What are major observational signatures in the dynamic chromosphere? 4. What might cause the heating of the upper atmosphere? Can Sound waves heat the upper atmosphere of the Sun? 5. Where does the solar wind come from? 15.1 Introduction The Sun’s atmosphere is composed of three major layers, the photosphere, chromosphere, and corona. The different layers have different temperatures, densities, and distinctive features, and are observed at different wavelengths. Structure of the Sun 15.2 Photosphere The photosphere is the thin (~500 km) bottom layer in the Sun’s atmosphere, where the atmosphere is optically thin, so that photons make their way out and travel unimpeded. Ex.1: the mean free path of photons in the photosphere and the radiative zone. The photosphere is seen in visible light continuum (so- called white light). Observable features on the photosphere include: • Limb darkening: from the disk center to the limb, the brightness fades. • Sun spots: dark areas of magnetic field concentration in low-mid latitudes. • Granulation: convection cells appearing as light patches divided by dark boundaries. Q: does the full moon exhibit limb darkening? Limb Darkening: limb darkening phenomenon indicates that temperature decreases with altitude in the photosphere. Modeling the limb darkening profile tells us the structure of the stellar atmosphere. -

SYNTHETIC SPECTRA for SUPERNOVAE Time a Basis for a Quantitative Interpretation. Eight Typical Spectra, Show

264 ASTRONOMY: PA YNE-GAPOSCHKIN AND WIIIPPLE PROC. N. A. S. sorption. I am indebted to Dr. Morgan and to Dr. Keenan for discussions of the problems of the calibration of spectroscopic luminosities. While these results are of a preliminary nature, it is apparent that spec- troscopic absolute magnitudes of the supergiants can be accurately cali- brated, even if few stars are available. For a calibration of a group of ten stars within Om5 a mean distance greater than one kiloparsec is necessary; for supergiants this requirement would be fulfilled for stars fainter than the sixth magnitude. The errors of the measured radial velocities need only be less than the velocity dispersion, that is, less than 8 km/sec. 1 Stebbins, Huffer and Whitford, Ap. J., 91, 20 (1940). 2 Greenstein, Ibid., 87, 151 (1938). 1 Stebbins, Huffer and Whitford, Ibid., 90, 459 (1939). 4Pub. Dom., Alp. Obs. Victoria, 5, 289 (1936). 5 Merrill, Sanford and Burwell, Ap. J., 86, 205 (1937). 6 Pub. Washburn Obs., 15, Part 5 (1934). 7Ap. J., 89, 271 (1939). 8 Van Rhijn, Gron. Pub., 47 (1936). 9 Adams, Joy, Humason and Brayton, Ap. J., 81, 187 (1935). 10 Merrill, Ibid., 81, 351 (1935). 11 Stars of High Luminosity, Appendix A (1930). SYNTHETIC SPECTRA FOR SUPERNOVAE By CECILIA PAYNE-GAPOSCHKIN AND FRED L. WHIPPLE HARVARD COLLEGE OBSERVATORY Communicated March 14, 1940 Introduction.-The excellent series of spectra of the supernovae in I. C. 4182 and N. G. C. 1003, published by Minkowski,I present for the first time a basis for a quantitative interpretation. Eight typical spectra, show- ing the major stages of the development during the first two hundred days, are shown in figure 1; they are directly reproduced from Minkowski's microphotometer tracings, with some smoothing for plate grain. -

Stellar Atmospheres I – Overview

Indo-German Winter School on Astrophysics Stellar atmospheres I { overview Hans-G. Ludwig ZAH { Landessternwarte, Heidelberg ZAH { Landessternwarte 0.1 Overview What is the stellar atmosphere? • observational view Where are stellar atmosphere models needed today? • ::: or why do we do this to us? How do we model stellar atmospheres? • admittedly sketchy presentation • which physical processes? which approximations? • shocking? Next step: using model atmospheres as \background" to calculate the formation of spectral lines •! exercises associated with the lecture ! Linux users? Overview . TOC . FIN 1.1 What is the atmosphere? Light emitting surface layers of a star • directly accessible to (remote) observations • photosphere (dominant radiation source) • chromosphere • corona • wind (mass outflow, e.g. solar wind) Transition zone from stellar interior to interstellar medium • connects the star to the 'outside world' All energy generated in a star has to pass through the atmosphere Atmosphere itself usually does not produce additional energy! What? . TOC . FIN 2.1 The photosphere Most light emitted by photosphere • stellar model atmospheres often focus on this layer • also focus of these lectures ! chemical abundances Thickness ∆h, some numbers: • Sun: ∆h ≈ 1000 km ? Sun appears to have a sharp limb ? curvature effects on the photospheric properties small solar surface almost ’flat’ • white dwarf: ∆h ≤ 100 m • red super giant: ∆h=R ≈ 1 Stellar evolution, often: atmosphere = photosphere = R(T = Teff) What? . TOC . FIN 2.2 Solar photosphere: rather homogeneous but ::: What? . TOC . FIN 2.3 Magnetically active region, optical spectral range, T≈ 6000 K c Royal Swedish Academy of Science (1000 km=tick) What? . TOC . FIN 2.4 Corona, ultraviolet spectral range, T≈ 106 K (Fe IX) c Solar and Heliospheric Observatory, ESA & NASA (EIT 171 A˚ ) What? . -

A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY of SUPERNOVAE MODELING By

A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF SUPERNOVAE MODELING by Chengdong Li BS, University of Science and Technology of China, 2006 MS, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Dietrich School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2013 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PHYSICS AND ASTRONOMY DEPARTMENT This dissertation was presented by Chengdong Li It was defended on January 22nd 2013 and approved by John Hillier, Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy Rupert Croft, Associate Professor, Department of Physics Steven Dytman, Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy Michael Wood-Vasey, Assistant Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy Andrew Zentner, Associate Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy Dissertation Director: John Hillier, Professor, Department of Physics and Astronomy ii Copyright ⃝c by Chengdong Li 2013 iii A COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF SUPERNOVAE MODELING Chengdong Li, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2013 The evolution of massive stars, as well as their endpoints as supernovae (SNe), is important both in astrophysics and cosmology. While tremendous progress towards an understanding of SNe has been made, there are still many unanswered questions. The goal of this thesis is to study the evolution of massive stars, both before and after explosion. In the case of SNe, we synthesize supernova light curves and spectra by relaxing two assumptions made in previous investigations with the the radiative transfer code cmfgen, and explore the effects of these two assumptions. Previous studies with cmfgen assumed γ-rays from radioactive decay deposit all energy into heating. However, some of the energy excites and ionizes the medium. -

Solar and Stellar Atmospheric Modeling Using the Pandora Computer Program

**TITLE** ASP Conference Series, Vol. **VOLUME**, **PUBLICATION YEAR** **EDITORS** Solar and Stellar Atmospheric Modeling Using the Pandora Computer Program Eugene H. Avrett and Rudolf Loeser Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA avrett,[email protected] Abstract. The Pandora computer program is a general-purpose non- LTE atmospheric modeling and spectrum synthesis code which has been used extensively to determine models of the solar atmosphere, other stel- lar atmospheres, and nebulae. The Pandora program takes into account, for a model atmosphere which is either planar or spherical, which is ei- ther stationary or in motion, and which may have an external source of illumination, the time-independent optically-thick non-LTE transfer of line and continuum radiation for multilevel atoms and multiple stages of ionization, with partial frequency redistribution, fluorescence, and other physical processes and constraints, including momentum balance and ra- diative energy balance with mechanical heating. Pandora includes the detailed effects of both particle diffusion and flow velocities in the equa- tions of ionization equilibrium. Such effects must be taken into account whenever the temperature gradient is large, such as in a chromosphere- corona transition region. 1. Introduction In this paper we first present a description of four different types of model atmo- sphere calculations: radiative equilibrium, general equilibrium, semi-empirical, and hydrodynamical, followed by a brief discussion of the important effects that should be included in model calculations. Then we describe the Pandora pro- gram which can be used for many different purposes, but is restricted at present by the assumptions of one-dimensionality and time-independence. -

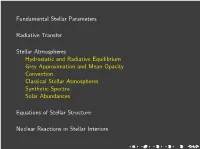

Fundamental Stellar Parameters Radiative Transfer Stellar

Fundamental Stellar Parameters Radiative Transfer Stellar Atmospheres Hydrostatic and Radiative Equilibrium Grey Approximation and Mean Opacity Convection Classical Stellar Atmospheres Synthetic Spectra Solar Abundances Equations of Stellar Structure Nuclear Reactions in Stellar Interiors Stellar Atmospheres Introduction Synthetic stellar spectra used for the determination of chemical element abun- dances were, until recently, based on one-dimensional model stellar atmospheres. At any optical (or geometric) depth, gravity is exactly balanced by pressure • (gas, electron and radiation) – hydrostatic equilibrium A constant temperature is maintained at every depth; radiative energy • received from below is equal to the energy radiated to layers above although frequency redistribution will have occurred – radiative equilibrium. Atmosphere assumed to be static and convection treated with crude mixing • length theory, using an empirically determined mixing length. Opacities needed are dependent on abundances sought. • Model stellar atmosphere may be obtained empirically, in the case of the Sun, by direct measurement of limb-darkening; for other cases where only Fν is ob- servable, an iterative calculation is needed with some realistic estimate used as a starting approximation. Hydrostatic Equilibrium { I P (r + dr) Consider a cylindrical element of mass ∆M and surface area dS dS between radii r and r + dr r + dr in a star. r Mass of gas in the star at smaller radii = m = m(r). O P (r) ∆M g 1 Hydrostatic Equilibrium { II Radial forces acting on the element Gravity (inward) • G m ∆M Fg = − r2 Pressure Difference (outward – net force due to difference in pressure • between upper and lower faces) F = P (r) dS P (r + dr) dS p − dP = P (r) dS P (r) + dr dS − dr × dP = dr dS − dr × If ρ is gas density in element ∆M = ρ dr dS. -

The Sun As a Guide to Stellar Physics This Page Intentionally Left Blank the Sun As a Guide to Stellar Physics

The Sun as a Guide to Stellar Physics This page intentionally left blank The Sun as a Guide to Stellar Physics Edited by Oddbjørn Engvold Professor emeritus, Rosseland Centre for Solar Physics, Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway Jean-Claude Vial Emeritus Senior Scientist, Institut d’Astrophysique Spatiale, CNRS-Universite´ Paris-Sud, Orsay, France Andrew Skumanich Emeritus Senior Scientist, High Altitude Observatory, National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Colorado, United States Elsevier Radarweg 29, PO Box 211, 1000 AE Amsterdam, Netherlands The Boulevard, Langford Lane, Kidlington, Oxford OX5 1GB, United Kingdom 50 Hampshire Street, 5th Floor, Cambridge, MA 02139, United States Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Details on how to seek permission, further information about the Publisher’s permissions policies and our arrangements with organizations such as the Copyright Clearance Center and the Copyright Licensing Agency, can be found at our website: www.elsevier.com/permissions. This book and the individual contributions contained in it are protected under copyright by the Publisher (other than as may be noted herein). Notices Knowledge and best practice in this field are constantly changing. As new research and experience broaden our understanding, changes in research methods, professional practices, or medical treatment may become necessary. Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. -

Stellar Atmospheres Now Becomes

9StellarAtmospheres Having developed the machinery to understand the spectral lines we see in stellar spectra, we’re now going to continue peeling our onion by examining its thin, outermost layer – the stellar atmosphere. Our goal is to understand how specific intensityI ν varies as a function of increasing depth in a stellar atmosphere, and also how it changes depending on the angle relative to the radial direction. 9.1 The Plane-parallel Approximation Fig. 14 gives a general overview of the geometry in what follows. The star is spherical (or close enough as makes no odds), but when we zoom in on a small enough patch the geometry becomes essentially plane-parallel. In that geometry,S ν andI ν depend on both altitudez as well as the angleθ from the normal direction. We assume that the radiation has no intrinsic dependence on eithert orφ – i.e., the radiation is in steady state and is isotropic. We need to develop a few new conventions before we can proceed. This is because in our definition of optical depth,dτ ν = ανds, the path length ds travels along the path. This Lagrangian description can be a bit annoying, so it’s common to formulate our radiative transfer in a path-independent, Eulerian, prescription. Let’s call our previously-defined optical depth (Eq. 71)τ ν� . We’ll then create a slightly altered definition of optical depth – a vertical,ingoing optical depth (this is the convention). The new definition is almost identical to the old one: (130)dτ = α dz ν − ν But now our optical depth, is vertical and oriented to measure inward, toward the star’s interior.