Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vampire Weekend Album Download Vampire Weekend Start '2021' with New 40:42 EP Featuring Two New Reinterpretations of Their Song

vampire weekend album download Vampire Weekend start '2021' with new 40:42 EP featuring two new reinterpretations of their song. For their new 40:42 EP released Thursday, the Grammy-winning band commissioned acclaimed jazz saxophonist Sam Gendel and the Connecticut rock quintet Goose to both create their own reinterpretations of the Father of the Bride album track. One twist though: Vampire Weekend gave Gendel and Goose the directive to turn their one minute and thirty-nine second long song into two twenty minute and twenty-one second versions (hence the title 40:42 ). In addition to fans being able to hear the two unique interpretations, Gendel and Goose both came with their own visuals. While Gendel's jazzy take comes with some improvisational animation, Goose chose to film themselves performing an intimate, up-close take on the song. Watch both Sam Gendel and Goose's versions of Vampire Weekend's "2021" above. The 40:42 EP is now available to stream across all digital platforms. Vampire Weekend. Purchase and download this album in a wide variety of formats depending on your needs. Buy the album Starting at £12.49. With the Internet able to build up or tear down artists almost as soon as they start practicing, the advance word and intense scrutiny doesn't always do a band any favors. By the time they've got a full-length album ready to go, the trend-spotters are already several Hot New Bands past them. Vampire Weekend started generating buzz in 2006 -- not long after they formed -- but their self-titled debut album didn't arrive until early 2008. -

Now Thats What I Call Love Songs 2013

Now thats what i call love songs 2013 Released three weeks prior to Valentine's Day , Now That's What I Call Love Songs compiles 18 contemporary hits dating back to. Now That's What I Call Love Songs (). TCRYA; 39 . Katy Perry - The One That Got Away (Official) Emeli Sandé - My Kind of Love. Tracklist with lyrics of the album NOW THAT'S WHAT I CALL LOVE SONGS [] from the compilation series Now That's What I Call Music! [] (compilation. This item:Now That's What I Call Love by Various Artists Audio CD £ In stock. Sold by Side . the rest of the year. Includes songs from Rihanna, Katy Perry, Cheryl Cole and Kylie among others. Byklordon 12 June Format: Audio. Jason DeruloSecret Love Song; Miley CyrusThe Climb; Nelly FurtadoI'm Like A Bird; BirdyWings; KeaneSomewhere Only We Know; Lady AntebellumNeed You. Now That's What I Call Love or Now Love is a double-disc compilation album released in the United Kingdom on 30 January Now Love features eleven songs which reached number one on the UK. Now That's What I Call Love features 20 tracks including songs from Colbie Caillat, Maroon 5, . Published on August 14, by Marion the Librarian. Various Artists - Now Love Songs - Music. $ Prime. NOW That's What I Call Love · Now Music . Published on July 17, by Amazon Fan. NOW Thats What I Call Love Songs! is a CD compilation that features some of the hottest pop artists CD Review - Reviewed by Kidzworld on Jan 29, VA – NOW That's What I Call Love Songs () [Deluxe Edition] 39 Love You Like a Love 3 · 40 Bleeding 3 · NOW That's. -

ამ რომანში ყველა კვდება Everybody Dies in This Novel Tbilisi: Bakur Sulakauri Publishing, 2018

European Union Prize for Literature Winning authors 2019 Printed by Bietlot in Belgium Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use that might be made of the following information. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2019 © European Union, 2019 Texts, translations, photos and other materials present in the publication have been licensed for use to the EUPL consortium by authors or other copyright holders who may prohibit reuse, reproduction or other use of their works. Photo credits Winners (page 2) Winners’ book covers Austria © Marianne Andrea Borowiec © Literaturverlag Droschl Finland © Mikko Rasila © Kustantama S&S France © Dominique Journet © Éditions Philippe Rey Georgia © Bakari Adamashvili © Bakur Sulakauri Publishing LTD Greece © Yiorgos Mavropoulos © Kastaniotis Editions Hungary © Gábor Valuska © Magvető Kiadó Ireland © Jonathan Ryder © Doubleday Ireland Italy © Elisa Pietrelli © minimum fax Lithuania © Daina Opolskaitė © Tyto alba Poland © Dawid Markiewicz © Fundacja Korporacja Ha!art Romania © Natalia Rusu © Editura Cartier Slovakia © Zuzana Vajdova © Marenčin PT Ukraine © Olha Zakrevska © Ranok Limited United Kingdom © Brian David Stevens © Bloomsbury Publishing Plc Please contact the EUPL consortium with any question about reuse or reproduction of specific text, translation, photo or other materials present. Print PDF ISBN 978-92-76-04610-3 ISBN 978-92-76-04574-8 doi:10.2766/810364 doi:10.2766/099051 NC-03-19-426-G0-C NC-03-19-426-G0-N European -

Molokai Planning Commission Regular Meeting February 10, 2010

(APPROVED: 04/14/10) MOLOKAI PLANNING COMMISSION REGULAR MEETING FEBRUARY 10, 2010 ** All documents, including written testimony, that was submitted for or at this meeting are filed in the minutes file and are available for public viewing at the Maui County Department of Planning, 250 S. High St., Wailuku, Maui, and at the Planning Commission Office at the Mitchell Pauole Center, Kaunakakai, Molokai. ** A. CALL TO ORDER The regular meeting of the Molokai Planning Commission was called to order by Chairperson Joseph Kalipi at 12:08 p.m., Wednesday, February 10, 2010, at the Mitchell Pauole Center Conference Room, Kaunakakai, Molokai. A quorum of the Commission was present. (See Record of Attendance.) Mr. Joseph Kalipi: If everybody would like to -- welcome everybody to the Molokai Planning Commission. We’ll call this meeting to order. Here with us from the Planning Department: our Program Administrator, Clayton Yoshida. We have Joe Alueta. Back there, Suzie Esmeralda, Clerk. Left of me here is Corporate Counsel, Michael Hopper. Representing the Planning Department, Jane Lovell. To my far right, Commissioner Williams, Commissioner Pescaia, Commissioner Sprinzel, Commissioner Bacon, and Commissioner Vice-Chair Steve Chaikin, and myself, I’ll be Chairing the meeting today, Commissioner Kalipi. B. PUBLIC TESTIMONY ON ANY PLANNING OR LAND USE ISSUE, except Contested Cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91 Mr. Kalipi: So at this time looking at our agenda, we would like to open the floor for any public testimony on any planning or land use issue, except the contested cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91. -

Roadside Picnic

ROADSIDE PICNIC Arkady and Boris Strugatsky Translated from the Russian by Antonina W. Bouis Cryptomaoist Editions FROM AN INTERVIEW BY A SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT FROM HARMONT RADIO WITH DOCTOR VALENTINE PILMAN, RECIPIENT OF THE NOBEL PRIZE IN PHYSICS FOR 19.. "I suppose that your first serious discovery, Dr. Pilman, should be considered what is now called the Pilman Radiant?" "I don't think so. The Pilman Radiant wasn't the first, nor was it serious, nor was it really a discovery. And it wasn't completely mine, either." "Surely you're joking, doctor. The Pilman Radiant is a concept known to every schoolchild." "That doesn't surprise me. According to some sources, the Pilman Radiant was discovered by a schoolboy. Unfortunately, I don't remember his name. Look it up in Stetson's History of the Visitation -- it's described in full detail there. His version is that the radiant was discovered by a schoolboy, that a college student published the coordinates, but that for some unknown reason it was named after me." "Yes, many amazing things can happen with a discovery. Would you mind explaining it to our listeners, Dr. Pilman?" "The Pilman Radiant is simplicity itself. Imagine that you spin a huge globe and you start firing bullets into it. The bullet holes would lie on the surface in a smooth curve. The whole point of what you call my first serious discovery lies in the simple fact that all six Visitation Zones are situated on the surface of our planet as though someone had taken six shots at Earth from a pistol located some- where along the Earth-Deneb line. -

Read an Excerpt

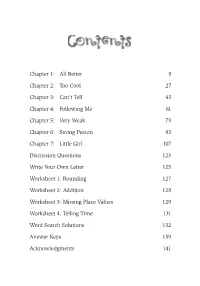

SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 7 Chapter 1: All Better 9 Chapter 2: Too Cool 27 Chapter 3: Can’t Tell 43 Chapter 4: Following Me 61 Chapter 5: Very Weak 79 Chapter 6: Strong Person 93 Chapter 7: Little Girl 107 Discussion Questions 123 Write Your Own Letter 125 Worksheet 1: Rounding 127 Worksheet 2: Addition 128 Worksheet 3: Missing Place Values 129 Worksheet 4: Telling Time 131 Word Search Solutions 132 Answer Keys 139 Acknowledgments 141 SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 9 Chapter 1 “W here are you going? I just know you don’t think you’re going with us, Morgan.” My new cousin Drake, who was my stepdaddy’s nephew, was acting like I had the plague or something. Placing my hands on my hips, I said back with attitude, “Yes, I’m going. That’s why I’m getting my coat. Can you tell Daddy Derek to hold on a second, please?” Since it was December, I also needed to grab my gloves and hat to keep warm. Just as I was heading quickly to my room, I felt somebody behind me stepping on my heel. I knew it was that rude Drake, and he didn’t even say that he was sorry. “No. I won’t tell him that,” Drake said, as he continued to follow me. SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 10 Speak Up! “Ouch!” I yelled out. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents A+Attitude Speak Up Something Special Right Thing No Fear MOODY PUBLISHERS CHICAGO Chapter 1: No Pep 9 Chapter 2: Real Sad 27 Chapter 3: Great News 41 Chapter 4: Low Energy 59 Chapter 5: Bright Spark 77 Chapter 6: Outgoing Kid 95 Chapter 7: Much Charm 111 Discussion Questions 127 Write Your Own Letter 129 Word Keep Book 130 Bonus English Grammar Pages 131 Word Search Solutions 135 Answer Keys 142 Acknowledgments 143 Chapter 1 “Morgan Noelle Love! You have got to get out of the car and let go of my waist, girl. I’m going to be late. You’re squeezing me like I’m a lemon and you’re trying to make lemonade.” My dad said this to me as I hugged him tighter than I used to hold my teddy bear, Goldie, when I was in kindergarten. Now that I was going into the second grade, there was a lot going on. Can’t a kid get a break? I am a big girl now. I don’t need Goldie to make sure I can sleep at night. I’m big enough to know that the bed bugs won’t bite. What I do need is my father, First-Class Captain, Monty Love. He’s leaving me again to go back to the U.S. Navy to serve our country off the coast of Africa. We spent the last two months together, and they were so great. Now our fun time is over. It made me sad to hear him say good-bye, not knowing when he was coming back to Georgia. -

The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan

Episode 34: The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan E34: THE POWER OF SIMPLY ANSWERING QUESTIONS WITH MARCUS SHERIDAN 00:00 Announcer: Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast. Your home for learning ways to attract more traffic to your websites, generate more leads, convert more leads into customers, and build stronger relationships with your customers. And now your hosts Justin Johnson and Ken Franzen. 00:18 Justin Johnson: Hey, hey, hey, Neon Noise nation. Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast, where we decode marketing and sales topics to help you grow your business. I am Justin and with me, I have my co- host, Ken. Ken, what's going on today? 00:31 Ken Franzen: Not too much, Justin. How are you doing yourself? 00:34 Justin Johnson: I am doing fantastic, thank you. I am extremely excited to talk to our featured guest today. He's got an awesome story, I can't wait to dive in. Today we have on Marcus Sheridan. He is called a web marketing guru by the New York Times. The story of how Marcus was able to save his swimming pool company, River Pools, from the economic crash of 2008 has been featured in multiple books, publications, and stories around the world. And it is also the inspiration for his newest book, "They Ask, You Answer," which is dubbed, "The number one marketing book to read in 2017" by Mashable. Today, Marcus has become a highly sought after global speaker and consultant in the digital sales and marketing space, working with hundreds of businesses and brands alike to become the most trusted voice in their industry while navigating the ultrafast rate of change occurring within consumers and buyers today. -

Cook to Learn: a Food-Focused Curriculum for Grades 3-5

Bank Street College of Education Educate Graduate Student Independent Studies Spring 5-1-2017 Cook to learn: A Food-Focused Curriculum for Grades 3-5 Ryan R. Cherecwich Bank Street College of Education, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://educate.bankstreet.edu/independent-studies Part of the Curriculum and Instruction Commons, Elementary Education Commons, and the Health and Physical Education Commons Recommended Citation Cherecwich, R. R. (2017). Cook to learn: A Food-Focused Curriculum for Grades 3-5. New York : Bank Street College of Education. Retrieved from https://educate.bankstreet.edu/independent-studies/178 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Educate. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Independent Studies by an authorized administrator of Educate. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Cook to Learn: A Food-Focused Curriculum for Grades 3-5 By Ryan R. Cherecwich Literacy and Childhood Education Mentor: Mollie Welsh Kruger Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master in Science of Education Bank Street College of Education 2017 2 Abstract Ryan R. Cherecwich Cook to Learn: A Food-Focused Curriculum for Grades 3-5 In this Integrated Master’s Project, I argue that a new curriculum is needed to address the following: (a) plant-based foods and from-scratch food preparation practices are strongly connected to positive outcomes for children, (b) diets high in processed foods can lead to negative health outcomes (c) students aged 8-10 are particularly well suited to learn more about food, (d) studying food offers many opportunities for interdisciplinary learning across many subjects (literacy, math, science and social studies) and (d) food-focused learning connects particularly well to common learning objectives for students in grades 3-5, yet (e) there is currently a dearth of appropriate curricular materials to meet the needs of today’s student population. -

STATE of ILLINOIS 94Th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE

STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “The House shall be in order. We shall be led in prayer today by Lee Crawford, the Assistant Pastor of the Victory Temple Church in Springfield. Members and their guests are asked to refrain from starting their laptops, turn off all cell phones and pagers and rise for the invocation and for the Pledge of Allegiance. Lee Crawford.” Pastor Crawford: “Let us pray. Most gracious God, who art in heaven, Father, we invoke Your glory into this house. We’re thankful to be able to come before Your holy presence and to declare that Your name alone is holy and undefiled. We ask that this day that Your kingdom would come, that Your will will be done on this earth as it is in heaven. We ask that You would give us this day our daily bread and the things that we have need of, for we are in need of wisdom, understanding, strength, both physical and spiritual. Father, I ask that You would forgive us all of our debts, as we forgive all of our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but we ask that You would deliver us from all evil. For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory this day and forever more. Amen.” Speaker Turner: “We shall be led in the Pledge today by the Gentleman from Tazewell, Representative Sommer.” Sommer – et al: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” 09400020.doc 1 STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “Roll Call for Attendance. -

Vampire Weekend Father of the Bride Album Download Zippyshare Vampire Weekend Father of the Bride Album Download Zippyshare

vampire weekend father of the bride album download zippyshare Vampire weekend father of the bride album download zippyshare. Father of the Bride is the fourth studio album by American indie rock band Vampire Weekend. It wasreleased on May 3, 2019 by Columbia Records as their first album on a major label, and was preceded by three double singles: "Harmony Hall" / "2021", "Sunflower" / "Big Blue" and "This Life" / "Unbearably White". The album is the band's first project in nearly six years, following Modern Vampires of the City (2013),and the group's first album since multi-instrumentalist and producer Rostam Batmanglij's departurefrom the group. The album was primarily produced by Modern Vampires of the City collaborator ArielRechtshaid and lead singer Ezra Koenig, and features numerous external collaborators, including Danielle Haim, Steve Lacy, Dave Macklovitch of Chromeo. DJ Dahi, David Longstreth, BloodPop, MarkRonson, and Batmanglij. Year: 2019 Genre: Indie Pop / Indie Rock Quality: mp3, 320 kbps. Track list: 01. Hold You Now (feat. Danielle Haim) 02. Harmony Hall 03. Bambina 04. This Life 05. Big Blue 06. How Long? 07. Unbearably White 08. Rich Man 09. Married in a Gold Rush (feat. Danielle Haim) 10. My Mistake 11. Sympathy 12. Sunflower (feat. Steve Lacy) 13. Flower Moon (feat. Steve Lacy) 14. 2021 15. We Belong Together (feat. Danielle Haim) 16. Stranger 17. Spring Snow 18. Jerusalem, New York, Berlin. The "lurching" art pop of "How Long?" contrasts jovial keyboards, sound effects, harmonies and funky 1970s-inspired guitars against dark and bitter lyrics about the potential demise of Los Angeles.[20][27][17] "Unbearably White" is a "colorful" art pop song, which grows and shifts to reveal isolated vocals, handbells, jazz fusion-inspired bass guitar, and orchestral surges, and lyrically discusses a failing relationship. -

Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Songs for cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson, Michael, "Songs for cripples" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2119 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Songs for Cripples by Michael Nelson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Rita Ciresi, M.F.A. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Ms. Suzanne Strempek Shea, M.F.A. Date of Approval: May 1, 2009 Keywords: Love, sex, God, abuse, death © Copyright 2009, Michael Nelson Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 Songs for Cripples 4 Sorehead 25 God’s Presents 41 In and Out of Holes 56 The Whispers of Little Pricks 81 Acts of Animals 99 Picture Books of Injured Children 115 Old Monkey 132 Epilogue 154 i Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson ABSTRACT Songs for Cripples is a fragmented novel or collection of stories which attempts to commingle the profound and the profane while scrutinizing the absurdity of inexplicable hope and the endless pursuit of avoiding loneliness. ii Introduction There is a woman I know who wears pink mittens in summer, only makes right-hand turns and carries a spiral notebook filled with numbers.