2017Wachira.Pdf (1.862Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Now Thats What I Call Love Songs 2013

Now thats what i call love songs 2013 Released three weeks prior to Valentine's Day , Now That's What I Call Love Songs compiles 18 contemporary hits dating back to. Now That's What I Call Love Songs (). TCRYA; 39 . Katy Perry - The One That Got Away (Official) Emeli Sandé - My Kind of Love. Tracklist with lyrics of the album NOW THAT'S WHAT I CALL LOVE SONGS [] from the compilation series Now That's What I Call Music! [] (compilation. This item:Now That's What I Call Love by Various Artists Audio CD £ In stock. Sold by Side . the rest of the year. Includes songs from Rihanna, Katy Perry, Cheryl Cole and Kylie among others. Byklordon 12 June Format: Audio. Jason DeruloSecret Love Song; Miley CyrusThe Climb; Nelly FurtadoI'm Like A Bird; BirdyWings; KeaneSomewhere Only We Know; Lady AntebellumNeed You. Now That's What I Call Love or Now Love is a double-disc compilation album released in the United Kingdom on 30 January Now Love features eleven songs which reached number one on the UK. Now That's What I Call Love features 20 tracks including songs from Colbie Caillat, Maroon 5, . Published on August 14, by Marion the Librarian. Various Artists - Now Love Songs - Music. $ Prime. NOW That's What I Call Love · Now Music . Published on July 17, by Amazon Fan. NOW Thats What I Call Love Songs! is a CD compilation that features some of the hottest pop artists CD Review - Reviewed by Kidzworld on Jan 29, VA – NOW That's What I Call Love Songs () [Deluxe Edition] 39 Love You Like a Love 3 · 40 Bleeding 3 · NOW That's. -

Molokai Planning Commission Regular Meeting February 10, 2010

(APPROVED: 04/14/10) MOLOKAI PLANNING COMMISSION REGULAR MEETING FEBRUARY 10, 2010 ** All documents, including written testimony, that was submitted for or at this meeting are filed in the minutes file and are available for public viewing at the Maui County Department of Planning, 250 S. High St., Wailuku, Maui, and at the Planning Commission Office at the Mitchell Pauole Center, Kaunakakai, Molokai. ** A. CALL TO ORDER The regular meeting of the Molokai Planning Commission was called to order by Chairperson Joseph Kalipi at 12:08 p.m., Wednesday, February 10, 2010, at the Mitchell Pauole Center Conference Room, Kaunakakai, Molokai. A quorum of the Commission was present. (See Record of Attendance.) Mr. Joseph Kalipi: If everybody would like to -- welcome everybody to the Molokai Planning Commission. We’ll call this meeting to order. Here with us from the Planning Department: our Program Administrator, Clayton Yoshida. We have Joe Alueta. Back there, Suzie Esmeralda, Clerk. Left of me here is Corporate Counsel, Michael Hopper. Representing the Planning Department, Jane Lovell. To my far right, Commissioner Williams, Commissioner Pescaia, Commissioner Sprinzel, Commissioner Bacon, and Commissioner Vice-Chair Steve Chaikin, and myself, I’ll be Chairing the meeting today, Commissioner Kalipi. B. PUBLIC TESTIMONY ON ANY PLANNING OR LAND USE ISSUE, except Contested Cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91 Mr. Kalipi: So at this time looking at our agenda, we would like to open the floor for any public testimony on any planning or land use issue, except the contested cases as defined in Hawaii Revised Statutes Section 91. -

Read an Excerpt

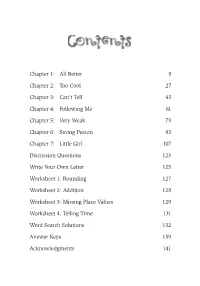

SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 7 Chapter 1: All Better 9 Chapter 2: Too Cool 27 Chapter 3: Can’t Tell 43 Chapter 4: Following Me 61 Chapter 5: Very Weak 79 Chapter 6: Strong Person 93 Chapter 7: Little Girl 107 Discussion Questions 123 Write Your Own Letter 125 Worksheet 1: Rounding 127 Worksheet 2: Addition 128 Worksheet 3: Missing Place Values 129 Worksheet 4: Telling Time 131 Word Search Solutions 132 Answer Keys 139 Acknowledgments 141 SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 9 Chapter 1 “W here are you going? I just know you don’t think you’re going with us, Morgan.” My new cousin Drake, who was my stepdaddy’s nephew, was acting like I had the plague or something. Placing my hands on my hips, I said back with attitude, “Yes, I’m going. That’s why I’m getting my coat. Can you tell Daddy Derek to hold on a second, please?” Since it was December, I also needed to grab my gloves and hat to keep warm. Just as I was heading quickly to my room, I felt somebody behind me stepping on my heel. I knew it was that rude Drake, and he didn’t even say that he was sorry. “No. I won’t tell him that,” Drake said, as he continued to follow me. SpeakUp 5.25X7.5 FINAL.qxp:RagontDesign 2/16/11 8:16 AM Page 10 Speak Up! “Ouch!” I yelled out. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents A+Attitude Speak Up Something Special Right Thing No Fear MOODY PUBLISHERS CHICAGO Chapter 1: No Pep 9 Chapter 2: Real Sad 27 Chapter 3: Great News 41 Chapter 4: Low Energy 59 Chapter 5: Bright Spark 77 Chapter 6: Outgoing Kid 95 Chapter 7: Much Charm 111 Discussion Questions 127 Write Your Own Letter 129 Word Keep Book 130 Bonus English Grammar Pages 131 Word Search Solutions 135 Answer Keys 142 Acknowledgments 143 Chapter 1 “Morgan Noelle Love! You have got to get out of the car and let go of my waist, girl. I’m going to be late. You’re squeezing me like I’m a lemon and you’re trying to make lemonade.” My dad said this to me as I hugged him tighter than I used to hold my teddy bear, Goldie, when I was in kindergarten. Now that I was going into the second grade, there was a lot going on. Can’t a kid get a break? I am a big girl now. I don’t need Goldie to make sure I can sleep at night. I’m big enough to know that the bed bugs won’t bite. What I do need is my father, First-Class Captain, Monty Love. He’s leaving me again to go back to the U.S. Navy to serve our country off the coast of Africa. We spent the last two months together, and they were so great. Now our fun time is over. It made me sad to hear him say good-bye, not knowing when he was coming back to Georgia. -

The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan

Episode 34: The Power of Simply Answering Questions with Marcus Sheridan E34: THE POWER OF SIMPLY ANSWERING QUESTIONS WITH MARCUS SHERIDAN 00:00 Announcer: Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast. Your home for learning ways to attract more traffic to your websites, generate more leads, convert more leads into customers, and build stronger relationships with your customers. And now your hosts Justin Johnson and Ken Franzen. 00:18 Justin Johnson: Hey, hey, hey, Neon Noise nation. Welcome to the Neon Noise podcast, where we decode marketing and sales topics to help you grow your business. I am Justin and with me, I have my co- host, Ken. Ken, what's going on today? 00:31 Ken Franzen: Not too much, Justin. How are you doing yourself? 00:34 Justin Johnson: I am doing fantastic, thank you. I am extremely excited to talk to our featured guest today. He's got an awesome story, I can't wait to dive in. Today we have on Marcus Sheridan. He is called a web marketing guru by the New York Times. The story of how Marcus was able to save his swimming pool company, River Pools, from the economic crash of 2008 has been featured in multiple books, publications, and stories around the world. And it is also the inspiration for his newest book, "They Ask, You Answer," which is dubbed, "The number one marketing book to read in 2017" by Mashable. Today, Marcus has become a highly sought after global speaker and consultant in the digital sales and marketing space, working with hundreds of businesses and brands alike to become the most trusted voice in their industry while navigating the ultrafast rate of change occurring within consumers and buyers today. -

STATE of ILLINOIS 94Th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE

STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “The House shall be in order. We shall be led in prayer today by Lee Crawford, the Assistant Pastor of the Victory Temple Church in Springfield. Members and their guests are asked to refrain from starting their laptops, turn off all cell phones and pagers and rise for the invocation and for the Pledge of Allegiance. Lee Crawford.” Pastor Crawford: “Let us pray. Most gracious God, who art in heaven, Father, we invoke Your glory into this house. We’re thankful to be able to come before Your holy presence and to declare that Your name alone is holy and undefiled. We ask that this day that Your kingdom would come, that Your will will be done on this earth as it is in heaven. We ask that You would give us this day our daily bread and the things that we have need of, for we are in need of wisdom, understanding, strength, both physical and spiritual. Father, I ask that You would forgive us all of our debts, as we forgive all of our debtors. Lead us not into temptation, but we ask that You would deliver us from all evil. For Thine is the kingdom and the power and the glory this day and forever more. Amen.” Speaker Turner: “We shall be led in the Pledge today by the Gentleman from Tazewell, Representative Sommer.” Sommer – et al: “I pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.” 09400020.doc 1 STATE OF ILLINOIS 94th GENERAL ASSEMBLY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES TRANSCRIPTION DEBATE 20th Legislative Day 2/24/2005 Speaker Turner: “Roll Call for Attendance. -

Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Songs for cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson, Michael, "Songs for cripples" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2119 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Songs for Cripples by Michael Nelson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Rita Ciresi, M.F.A. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Ms. Suzanne Strempek Shea, M.F.A. Date of Approval: May 1, 2009 Keywords: Love, sex, God, abuse, death © Copyright 2009, Michael Nelson Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 Songs for Cripples 4 Sorehead 25 God’s Presents 41 In and Out of Holes 56 The Whispers of Little Pricks 81 Acts of Animals 99 Picture Books of Injured Children 115 Old Monkey 132 Epilogue 154 i Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson ABSTRACT Songs for Cripples is a fragmented novel or collection of stories which attempts to commingle the profound and the profane while scrutinizing the absurdity of inexplicable hope and the endless pursuit of avoiding loneliness. ii Introduction There is a woman I know who wears pink mittens in summer, only makes right-hand turns and carries a spiral notebook filled with numbers. -

Buntgemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB

Seite 1 von 284 -BuntGemischt 7356 Titel, 19,2 Tage, 43,26 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Hey, hey Helen 3:15 ABBA - ABBA - 1975 (LP-192) ABBA 2 Eagle 5:48 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 3 Take a chance on me 4:00 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 4 One man, one woman 4:34 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 5 The name of the game 4:53 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 6 Move on 4:39 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 7 Thank you for the music 3:47 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 8 I wonder 4:31 The Album - ABBA -1977 (LP-192) ABBA 9 When i kissed the teacher 3:01 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 10 Dancing queen 3:51 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 11 My love, my life 3:51 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 12 Knowing me, knowing you 4:01 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 13 Money money money 3:06 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 14 That's me 3:16 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 15 Why did it have to be me 3:19 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 16 Tiger 2:54 Arrival - ABBA - 1976 (LP) ABBA 17 The winner takes it all 4:56 Golden Love Songs 15 - I'll Write A Song For You (RS) ABBA 18 Fernando 4:15 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 19 S.O.S. 3:22 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 20 Ring ring 3:07 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 21 Nina, pretty ballerina 2:53 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 22 Honey honey 2:57 Greatest Hits (30th Anniversary Edition) - ABBA - Comp 2006 (… ABBA 23 So long -

Orange County Board of Education Meeting, January 13, 2016

Orange County Board of Education Meeting, January 13, 2016 Call to Order Hammond: Alright the Orange County Board of Education is getting started here and as always I read a little something here and you know for a couple of our honored guests here as I see we’ve really packed out the place and um, basically you all know the drill. It’s like in our meetings are held usually at 11:00 am and anybody wanting to address the board on any matter, whether it appears or not on the agenda, please fill out an “a request to address the board card” which is on the table near the door. If you got any questions obviously our staff can help you out. Each person is allowed 3 minutes and with that I will get ready to go. Ron, counselor, quick question for you. And thank you for the awesome job you and your staff do. Is there anything you feel on the agenda that there’s any conflict? Wenkart: Um, no. Not at this time. I just wanted to point out that when there’s a difference of opinion between an individual board member and myself on a legal opinion, that doesn’t constitute a conflict of interest. But when there is one I will certainly let the board know. Thank you. Hammond: Awesome. Thanks Ron. Appreciate that. So for the benefit of the record this regular meeting of the Orange County Board of Education is called to order and with that we will now start off with our invocation and we have our good friend Pastor Gale Oliver back once again and would you be so kind as to lead us sir. -

Cover 02.07 1 5/1/07, 4:42:18 Pm Line Dance Weekends from HOLIDAYS 20072007 £69.00

TThehe mmonthlyonthly mmagazineagazine dedicateddedicated ttoo LLineine ddancingancing IIssue:ssue: 112929 • FFebruaryebruary 22007007 • ££33 • BBarryarry & DDariari AAnnenne AAmatomato • BBritishritish MMastersasters IInn LLineine • KKateate SSalaala iinn TTurkeyurkey • A DayDay InIn TheThe LLifeife ooff GGerieri MorrisonMorrison IITALIANTALIAN LOVELOVE SSTORYTORY 02 Patrizio shares his Valentine’s secrets 771366 650031 9 14 DANCES INCLUDING: SAY HEY · BEFORE YOU LEAVE · WRAP AROUND · WANT 2 cover 02.07 1 5/1/07, 4:42:18 pm Line Dance Weekends from HOLIDAYS 20072007 £69.00 Carlisle Canters Torquay Toe Tappers at Grosvenor Hotel at Crown and Mitre Hotel 3 Days /2 nights SELF DRIVE - £89 Artists- Real Deal (Saturday) Dance Instruction and Disco: Richard and Susan Wynn Starts: Friday 13 April Finishes: Sunday 15 April 2007 3 Days /2 nights SELF DRIVE - £89 Artist- Billy Bubba King (Saturday) Dance Instruction and Disco: Chris and Sandy Jackson Starts: Friday 5 Oct Finishes: Sunday 7 Oct 2007 3 Days /2 nights SELF DRIVE - £89 Artists – Rick Storm (Saturday) Dance Instruction and Disco: Richard and Susan Wynn Starts: Friday 16 Nov Finishes: Sunday 18 Nov 2007 3 Days /2 nights SELF DRIVE - £99 BY COACH - £129 Artists- Glenn Rogers (Friday) M T Allan (Saturday) St. Annes Shimmys at Langdales Hotel Dance Instruction and Disco: Yvonne Anderson 3 Days /2 nights SELF DRIVE - £93 Starts: Friday 16 Feb Finishes: Sunday 18 Feb 2007 Dance Instruction and Disco: Brenda Scott Coach available from Scotland, Tyneside & Teesside. Starts: Friday 11 May Finishes: -

Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Scholar Commons | University of South Florida Research University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2009 Songs for cripples Michael Nelson University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Nelson, Michael, "Songs for cripples" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2119 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Songs for Cripples by Michael Nelson A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Rita Ciresi, M.F.A. Lawrence Broer, Ph.D. Ms. Suzanne Strempek Shea, M.F.A. Date of Approval: May 1, 2009 Keywords: Love, sex, God, abuse, death © Copyright 2009, Michael Nelson Table of Contents Abstract ii Introduction 1 Songs for Cripples 4 Sorehead 25 God’s Presents 41 In and Out of Holes 56 The Whispers of Little Pricks 81 Acts of Animals 99 Picture Books of Injured Children 115 Old Monkey 132 Epilogue 154 i Songs for Cripples Michael Nelson ABSTRACT Songs for Cripples is a fragmented novel or collection of stories which attempts to commingle the profound and the profane while scrutinizing the absurdity of inexplicable hope and the endless pursuit of avoiding loneliness. -

All That I Am

All That I Am.. Count: 48 Wall: 4 Level: Intermediate level Choreographer: Neville Fitzgerald (UK) & Julie Harris (UK) Music: This Life - LeAnn Rimes : (Album: Whatever We Wanna) Starts on Vocal (24 Counts) Diagonal Walk, Step, 1/2 Pivot, Walk, 1/2 Turn, 1/4 Turn. 1-3 Step forward on Left 1/8 turn to Right, (1.30) step forward on Right, pivot 1/2 turn to Left. (7.30) 4-6 Step forward on Right, make 1/2 turn to Right stepping back on Left, (1.30) 1/4 turn to Right stepping forward on Right. (4.30) Diagonal Walk, Step, 1/2 Pivot, Walk, 1/2 Turn, 1/4 Turn. 1-3 Step forward on Left, step forward on Right, pivot 1/2 turn to Left. (10.30) 4-6 Step forward on Right, make 1/2 turn to Right stepping back on Left, (4.30) 1/4 turn to Right stepping forward on Right. (7.30) Twinkle Step, Cross Side Behind. 1-3 Cross step Left over Right, step Right to Right side, step Left to Left side. (straighten up to face 6.00 Wall) 4-6 Cross step Right over Left, step Left to Left side, cross step Right behind Left. Side, Drag, 1/4, 1/2 , Back. 1-3 Step Left large step to Left side, drag Right toe next to Left over 2 counts. 4-6 Make 1/4 turn to Right stepping forward on Right, 1/2 turn to Right stepping back on Left,step back on Right. Basic Waltz Back, Step, 1/4 , 1/2 , 1-3 Step Back on Left, step Right next to Left, step Left in place.