Cretaceous) of Southern Appalachia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Cretaceous Sequences and Sea-Level History, New Jersey Coastal Plain

Upper Cretaceous sequences and sea-level history, New Jersey Coastal Plain Kenneth G. Miller² Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA Peter J. Sugarman New Jersey Geological Survey, P.O. Box 427, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, USA James V. Browning Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA Michelle A. Kominz Department of Geosciences, Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan 49008-5150, USA Richard K. Olsson Mark D. Feigenson John C. HernaÂndez Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, New Jersey 08854, USA ABSTRACT pean sections, and Russian platform BACKGROUND outcrops points to a global cause. Because We developed a Late Cretaceous sea- backstripping, seismicity, seismic strati- Predictable, recurring sequences bracketed level estimate from Upper Cretaceous se- graphic data, and sediment-distribution by unconformities comprise the building quences at Bass River and Ancora, New patterns all indicate minimal tectonic ef- blocks of the stratigraphic record. Exxon Pro- Jersey (ODP [Ocean Drilling Program] Leg fects on the New Jersey Coastal Plain, we duction Research Company (EPR) de®ned a 174AX). We dated 11±14 sequences by in- interpret that we have isolated a eustatic depositional sequence as a ``stratigraphic unit tegrating Sr isotope and biostratigraphy signature. The only known mechanism composed of a relatively conformable succes- (age resolution 60.5 m.y.) and then esti- that can explain such global changesÐ sion of genetically related strata and bounded mated paleoenvironmental changes within glacio-eustasyÐis consistent with forami- at its top and base by unconformities or their the sequences from lithofacies and biofacies niferal d18O data. -

A New Hadrosauroid Dinosaur from the Early Late Cretaceous of Shanxi Province, China

A New Hadrosauroid Dinosaur from the Early Late Cretaceous of Shanxi Province, China Run-Fu Wang1, Hai-Lu You2*, Shi-Chao Xu1, Suo-Zhu Wang1,JianYi1, Li-Juan Xie1, Lei Jia1, Ya-Xian Li1 1 Shanxi Museum of Geological and Mineral Science and Technology, Taiyuan, Shanxi Province, People’s Republic of China, 2 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, People’s Republic of China Abstract Background: The origin of hadrosaurid dinosaurs is far from clear, mainly due to the paucity of their early Late Cretaceous close relatives. Compared to numerous Early Cretaceous basal hadrosauroids, which are mainly from Eastern Asia, only six early Late Cretaceous (pre-Campanian) basal hadrosauroids have been found: three from Asia and three from North America. Methodology/Principal Findings: Here we describe a new hadrosauroid dinosaur, Yunganglong datongensis gen. et sp. nov., from the early Late Cretaceous Zhumapu Formation of Shanxi Province in northern China. The new taxon is represented by an associated but disarticulated partial adult skeleton including the caudodorsal part of the skull. Cladistic analysis and comparative studies show that Yunganglong represents one of the most basal Late Cretaceous hadrosauroids and is diagnosed by a unique combination of features in its skull and femur. Conclusions/Significance: The discovery of Yunganglong adds another record of basal Hadrosauroidea in the early Late Cretaceous, and helps to elucidate the origin and evolution of Hadrosauridae. Citation: Wang R-F, You H-L, Xu S-C, Wang S-Z, Yi J, et al. -

The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Second Edition

MASS ESTIMATES - DINOSAURS ETC (largely based on models) taxon k model femur length* model volume ml x specific gravity = model mass g specimen (modeled 1st):kilograms:femur(or other long bone length)usually in decameters kg = femur(or other long bone)length(usually in decameters)3 x k k = model volume in ml x specific gravity(usually for whole model) then divided/model femur(or other long bone)length3 (in most models femur in decameters is 0.5253 = 0.145) In sauropods the neck is assigned a distinct specific gravity; in dinosaurs with large feathers their mass is added separately; in dinosaurs with flight ablity the mass of the fight muscles is calculated separately as a range of possiblities SAUROPODS k femur trunk neck tail total neck x 0.6 rest x0.9 & legs & head super titanosaur femur:~55000-60000:~25:00 Argentinosaurus ~4 PVPH-1:~55000:~24.00 Futalognkosaurus ~3.5-4 MUCPv-323:~25000:19.80 (note:downsize correction since 2nd edition) Dreadnoughtus ~3.8 “ ~520 ~75 50 ~645 0.45+.513=.558 MPM-PV 1156:~26000:19.10 Giraffatitan 3.45 .525 480 75 25 580 .045+.455=.500 HMN MB.R.2181:31500(neck 2800):~20.90 “XV2”:~45000:~23.50 Brachiosaurus ~4.15 " ~590 ~75 ~25 ~700 " +.554=~.600 FMNH P25107:~35000:20.30 Europasaurus ~3.2 “ ~465 ~39 ~23 ~527 .023+.440=~.463 composite:~760:~6.20 Camarasaurus 4.0 " 542 51 55 648 .041+.537=.578 CMNH 11393:14200(neck 1000):15.25 AMNH 5761:~23000:18.00 juv 3.5 " 486 40 55 581 .024+.487=.511 CMNH 11338:640:5.67 Chuanjiesaurus ~4.1 “ ~550 ~105 ~38 ~693 .063+.530=.593 Lfch 1001:~10700:13.75 2 M. -

DINOQUEST: a TROPICAL TREK THROUGH TIME Featured Dinosaurs and Reptiles

DINOQUEST: A TROPICAL TREK THROUGH TIME Featured Dinosaurs and Reptiles BAMBIRAPTORS (AND EGG NEST) (BAM-bee-RAP-tors) Name Means : “Baby Raider” Description : A tiny, bird-like dinosaur that is believed to have been covered in feathers and fuzz, similar to that of a baby bird. It had long arms and hands, with a mouth full of sharp teeth and a claw similar to that of the Velociraptor. Lived : Late Cretaceous period Fossils Found : Montana, U.S. Fun Fact : Bambiraptor is an important piece of the puzzle linking dinosaurs to birds. A 90-percent complete skeleton was discovered by a 14-year-old boy in 1995. Installation Dimensions : Four four-foot-long dinosaurs; two 30-inch-diameter egg nests CITIPATI (AND EGG NEST) (sit-ih-PA-tee) Name Means : “Funeral Pyre Lord” Description : Citipati’s skull was unusually short and ended in a toothless beak. It is one of the best known of the bird-like dinosaurs. It has an unusually long neck and shortened tail, compared to most other theropods. Lived : Cretaceous period Fossils Found : Mongolia Fun Fact : At least four specimens of Citipati have been found sitting on their nests, indicating that Citipati took care of its young like modern birds. Installation Dimensions : Three three-and-a-half-foot-long dinosaurs; two 30-inch-diameter egg nests COMPSOGNATHUS (AND EGG NEST) (komp-sog-NAY-thus) Name Means : “Pretty Jaw” Description : The Compsognathus was a bird-like carnivore with short arms, two-clawed fingers, long legs and three-toed feet. It had a long neck and small head with pointy teeth. -

A Phylogenetic Analysis of the Basal Ornithischia (Reptilia, Dinosauria)

A PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THE BASAL ORNITHISCHIA (REPTILIA, DINOSAURIA) Marc Richard Spencer A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE December 2007 Committee: Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor Don C. Steinker Daniel M. Pavuk © 2007 Marc Richard Spencer All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Margaret M. Yacobucci, Advisor The placement of Lesothosaurus diagnosticus and the Heterodontosauridae within the Ornithischia has been problematic. Historically, Lesothosaurus has been regarded as a basal ornithischian dinosaur, the sister taxon to the Genasauria. Recent phylogenetic analyses, however, have placed Lesothosaurus as a more derived ornithischian within the Genasauria. The Fabrosauridae, of which Lesothosaurus was considered a member, has never been phylogenetically corroborated and has been considered a paraphyletic assemblage. Prior to recent phylogenetic analyses, the problematic Heterodontosauridae was placed within the Ornithopoda as the sister taxon to the Euornithopoda. The heterodontosaurids have also been considered as the basal member of the Cerapoda (Ornithopoda + Marginocephalia), the sister taxon to the Marginocephalia, and as the sister taxon to the Genasauria. To reevaluate the placement of these taxa, along with other basal ornithischians and more derived subclades, a phylogenetic analysis of 19 taxonomic units, including two outgroup taxa, was performed. Analysis of 97 characters and their associated character states culled, modified, and/or rescored from published literature based on published descriptions, produced four most parsimonious trees. Consistency and retention indices were calculated and a bootstrap analysis was performed to determine the relative support for the resultant phylogeny. The Ornithischia was recovered with Pisanosaurus as its basalmost member. -

A Revised Taxonomy of the Iguanodont Dinosaur Genera and Species

ARTICLE IN PRESS + MODEL Cretaceous Research xx (2007) 1e25 www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes A revised taxonomy of the iguanodont dinosaur genera and species Gregory S. Paul 3109 North Calvert Station, Side Apartment, Baltimore, MD 21218-3807, USA Received 20 April 2006; accepted in revised form 27 April 2007 Abstract Criteria for designating dinosaur genera are inconsistent; some very similar species are highly split at the generic level, other anatomically disparate species are united at the same rank. Since the mid-1800s the classic genus Iguanodon has become a taxonomic grab-bag containing species spanning most of the Early Cretaceous of the northern hemisphere. Recently the genus was radically redesignated when the type was shifted from nondiagnostic English Valanginian teeth to a complete skull and skeleton of the heavily built, semi-quadrupedal I. bernissartensis from much younger Belgian sediments, even though the latter is very different in form from the gracile skeletal remains described by Mantell. Currently, iguanodont remains from Europe are usually assigned to either robust I. bernissartensis or gracile I. atherfieldensis, regardless of lo- cation or stage. A stratigraphic analysis is combined with a character census that shows the European iguanodonts are markedly more morpho- logically divergent than other dinosaur genera, and some appear phylogenetically more derived than others. Two new genera and a new species have been or are named for the gracile iguanodonts of the Wealden Supergroup; strongly bipedal Mantellisaurus atherfieldensis Paul (2006. Turning the old into the new: a separate genus for the gracile iguanodont from the Wealden of England. In: Carpenter, K. (Ed.), Horns and Beaks: Ceratopsian and Ornithopod Dinosaurs. -

Zootaxa, Glishades Ericksoni, a New Hadrosauroid

Zootaxa 2452: 1–17 (2010) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2010 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Glishades ericksoni, a new hadrosauroid (Dinosauria: Ornithopoda) from the Late Cretaceous of North America ALBERT PRIETO-MÁRQUEZ Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024, USA. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new genus and species of hadrosauroid dinosaur, Glishades ericksoni, is described based on paired partial premaxillae collected from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation of Montana, in the Western Interior of the United States of America. This taxon is diagnosed on the basis of a unique combination of characters: absence of everted oral margin, arcuate oral margin with wide and straight, obliquely oriented, and undeflected anterolateral corner, grooved transversal thickening on ventral surface of premaxilla posterior to denticulate oral margin, and foramina on anteromedial surface above oral edge and adjacent to proximal end of narial bar. Maximum parsimony analysis positioned G. ericksoni as a derived hadrosauroid. Exclusion of G. ericksoni from Hadrosauridae was unambiguously supported by the lack in AMNH 27414 of a dorsomedially reflected premaxillary oral margin. Furthermore, the maximum agreement subtree positioned G. ericksoni as the sister taxon to Bactrosaurus johnsoni. This position was unambiguously supported by posteroventral thickening on the ventral surface of the premaxilla (independently derived in saurolophid hadrosaurids and Ouranosaurus nigeriensis) and having foramina on each premaxilla on the anterior surface, adjacent to the parasagittal plane of the rostrum (reconstructed as independently derived in Brachylophosaurus canadensis, Maiasaura peeblesorum, and Edmontosaurus annectens). -

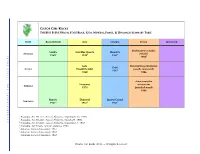

State Rocks Table.Pdf

GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Basilosaurus cetoides Marble Star Blue Quartz Hematite ALABAMA [whale] 19691 19902 19673 19844 Jade Mammuthus primigenius Gold ALASKA [Nephrite Jade] [woolly mammoth] 1967 1968 1986 STATE ROCKS STATE – Araucarioxylon Turquoise arizonicum ARIZONA 1974 [petrified wood] 1988 Bauxite Diamond Quartz Crystal ARKANSAS 19675 19676 19677 1 Alabama, Act 69-755, Acts of Alabama, September 12, 1969. 2 Alabama, Act 90-203. Acts of Alabama, March 29, 1990. GATORGIRLROCKS.COM GATORGIRLROCKS.COM 3 Alabama, Act 67-503, Acts of Alabama, September 7, 1967. 4 Alabama, Act 84-66, Acts of Alabama, 1984. 5 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 6 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. 7 Arkansas General Assembly 1967. ©Gator Girl Rocks (2012) – All Rights Reserved GATOR GIRL ROCKS THE BEST EVER OFFICIAL STATE ROCK, GEM, MINERAL, FOSSIL, & DINOSAUR SUMMARY TABLE STATE ROCK/(STONE) GEM MINERAL FOSSIL DINOSAUR Smilodon californicus Serpentine Benitoite Native Gold CALIFORNIA 8 9 10 [saber-tooth cat] 1965 1985 1965 11 1973 Stegosaurus stenops Yule Marble Aquamarine Rhodochrosite COLORADO [dinosaur] 200412 197113 200214 198215 STATE ROCKS STATE Garnet Eubrontes Giganteus – CONNECTICUT [almandine garnet] [dinosaur tracks] 197716 1991 8 California Gov. Code § 425.2. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. 1) was signed by Govenor Brown on April 20, 1965. California designated the very first official state rock with this legislation (which also created the first official state mineral). 9 California State Legislature October 1, 1985. 10 California Gov. Code § 425.1. Senate Bill 265 (Laws Chap. 89, Sec. -

Highly Diversified Late Cretaceous Fish Assemblage Revealed by Otoliths (Ripley Formation and Owl Creek Formation, Northeast Mississippi, Usa)

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 126(1): 111-155. March 2020 HIGHLY DIVERSIFIED LATE CRETACEOUS FISH ASSEMBLAGE REVEALED BY OTOLITHS (RIPLEY FORMATION AND OWL CREEK FORMATION, NORTHEAST MISSISSIPPI, USA) GARY L. STRINGER1, WERNER SCHWARZHANS*2 , GEORGE PHILLIPS3 & ROGER LAMBERT4 1Museum of Natural History, University of Louisiana at Monroe, Monroe, Louisiana 71209, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] 3Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, 2148 Riverside Drive, Jackson, Mississippi 39202, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4North Mississippi Gem and Mineral Society, 1817 CR 700, Corinth, Mississippi, 38834, USA. E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author To cite this article: Stringer G.L., Schwarzhans W., Phillips G. & Lambert R. (2020) - Highly diversified Late Cretaceous fish assemblage revealed by otoliths (Ripley Formation and Owl Creek Formation, Northeast Mississippi, USA). Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 126(1): 111-155. Keywords: Beryciformes; Holocentriformes; Aulopiformes; otolith; evolutionary implications; paleoecology. Abstract. Bulk sampling and extensive, systematic surface collecting of the Coon Creek Member of the Ripley Formation (early Maastrichtian) at the Blue Springs locality and primarily bulk sampling of the Owl Creek Formation (late Maastrichtian) at the Owl Creek type locality, both in northeast Mississippi, USA, have produced the largest and most highly diversified actinopterygian otolith (ear stone) assemblage described from the Mesozoic of North America. The 3,802 otoliths represent 30 taxa of bony fishes representing at least 22 families. In addition, there were two different morphological types of lapilli, which were not identifiable to species level. -

Notes on British Dinosaurs. Part I: Hypsilophodon

Dr. Francis Baron Nopcsa—British Dinosaurs. 203 II.—NOTES ON BRITISH DINOSAURS. PAET I: ffrpsiLOPHODOK. By Dr. FRANCIS BARON NOPCSA. (WITH A PAGE-ILLUSTRATION.) URING a recent stay in London the kindness of Dr. A. S. Woodward enabled me to study some of the splendid Dinosaurian remainD s in the British Museum. Having principally occupied myself till now with Ornithopodous Dinosaurs, first of all Hypsilophodon attracted my attention, and my expectation that this type would prove to be the clue for the- understanding of all the other Orthopoda has been perfectly fulfilled. Hypsilophodon was described and figured at various times by Owen, Huxley, and Hulke; a restoration of this animal was given by Marsh in the GEOLOGICAL MAGAZINE for 1896 (p. 6, Fig. 2), and the complete bibliographical list concerning this Dinosaur is compiled in my paper "Synopsis und Abstammung der Dinosaurier" (Foldtani Xozlony, 1901, Budapest). In consequence of our more recent knowledge of Dinosaurs in general I managed to detect some new points of remarkable interest. Mandible. What Hulke, in describing the Hypsilophodon skull, No. 110, supposed to be the parietal, frontal, and post-frontal bones (Phil. Trans., 1882, pi. lxxi, fig. 1, pa., fr., ps.f.), turned out to be the outer view of a complete right mandibular ramus, so that the parietal changes into an articular, the frontal becomes the dentary, and the post-frontal the coronoid bone. This piece (p. 207, Fig. 4) is, in fact, the finest mandibulum of Hypsilophodon I have seen in the whole collection, and as such worthy to be refigured. The general outline of the mandibulum, with its strongly ab- breviated post-coronoidal part and its blunt processus coronoideum, reminds one somewhat of the under jaw of Placodus gigas, though it differs of course in nearly every detail, being built up after the Iguanodon type. -

The Dinosaurs Transylvanian Province in Hungary

COMMUNICATIONS OF THE YEARBOOK OF THE ROYAL HUNGARIAN GEOLOGICAL IMPERIAL INSTITUTE ================================================================== VOL. XXIII, NUMBER 1. ================================================================== THE DINOSAURS OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN PROVINCE IN HUNGARY. BY Dr. FRANZ BARON NOPCSA. WITH PLATES I-IV AND 3 FIGURES IN THE TEXT. Published by The Royal Hungarian Geological Imperial Institute which is subject to The Royal Hungarian Agricultural Ministry BUDAPEST. BOOK-PUBLISHER OF THE FRANKLIN ASSOCIATION. 1915. THE DINOSAURS OF THE TRANSYLVANIAN PROVINCE IN HUNGARY. BY Dr. FRANZ BARON NOPCSA. WITH PLATES I-IV AND 3 FIGURES IN THE TEXT. Mit. a. d. Jahrb. d. kgl. ungar. Geolog. Reichsanst. XXIII. Bd. 1 heft I. Introduction. Since it appears doubtful when my monographic description of the dinosaurs of Transylvania1 that formed my so-to-speak preparatory works to my current dinosaur studies can be completed, due on one hand to outside circumstances, but on the other hand to the new arrangement of the vertebrate material in the kgl. ungar. geologischen Reichsanstalt accomplished by Dr. KORMOS, the necessity emerged of also exhibiting some of the dinosaur material located here, so that L. v. LÓCZY left the revision to me; I view the occasion, already briefly anticipating my final work at this point, to give diagnoses of the dinosaurs from the Transylvanian Cretaceous known up to now made possible from a systematic division of the current material, as well as to discuss their biology. The reptile remains known from the Danian of Transylvania will be mentioned only incidentally. Concerning the literature, I believe in refraining from more exact citations, since this work presents only a preliminary note. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex By Karen E. Poole B.A. in Geology, May 2004, University of Pennsylvania M.A. in Earth and Planetary Sciences, August 2008, Washington University in St. Louis A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2015 Dissertation Directed by Catherine Forster Professor of Biology The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Karen Poole has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 10th, 2015. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex Karen E. Poole Dissertation Research Committee: Catherine A. Forster, Professor of Biology, Dissertation Director James M. Clark, Ronald Weintraub Professor of Biology, Committee Member R. Alexander Pyron, Robert F. Griggs Assistant Professor of Biology, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Karen Poole All rights reserved iii Dedication To Joseph Theis, for his unending support, and for always reminding me what matters most in life. To my parents, who have always encouraged me to pursue my dreams, even those they didn’t understand. iv Acknowledgements First, a heartfelt thank you is due to my advisor, Cathy Forster, for giving me free reign in this dissertation, but always providing valuable commentary on any piece of writing I sent her, no matter how messy.