Upper Cretaceous Sequences and Sea-Level History, New Jersey Coastal Plain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constraints on the Timescale of Animal Evolutionary History

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org Constraints on the timescale of animal evolutionary history Michael J. Benton, Philip C.J. Donoghue, Robert J. Asher, Matt Friedman, Thomas J. Near, and Jakob Vinther ABSTRACT Dating the tree of life is a core endeavor in evolutionary biology. Rates of evolution are fundamental to nearly every evolutionary model and process. Rates need dates. There is much debate on the most appropriate and reasonable ways in which to date the tree of life, and recent work has highlighted some confusions and complexities that can be avoided. Whether phylogenetic trees are dated after they have been estab- lished, or as part of the process of tree finding, practitioners need to know which cali- brations to use. We emphasize the importance of identifying crown (not stem) fossils, levels of confidence in their attribution to the crown, current chronostratigraphic preci- sion, the primacy of the host geological formation and asymmetric confidence intervals. Here we present calibrations for 88 key nodes across the phylogeny of animals, rang- ing from the root of Metazoa to the last common ancestor of Homo sapiens. Close attention to detail is constantly required: for example, the classic bird-mammal date (base of crown Amniota) has often been given as 310-315 Ma; the 2014 international time scale indicates a minimum age of 318 Ma. Michael J. Benton. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Philip C.J. Donoghue. School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1RJ, U.K. [email protected] Robert J. -

The Geology, Paleontology and Paleoecology of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation

The Geology, Paleontology and Paleoecology of the Cerro Fortaleza Formation, Patagonia (Argentina) A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Victoria Margaret Egerton in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 © Copyright 2011 Victoria M. Egerton. All Rights Reserved. ii Dedications To my mother and father iii Acknowledgments The knowledge, guidance and commitment of a great number of people have led to my success while at Drexel University. I would first like to thank Drexel University and the College of Arts and Sciences for providing world-class facilities while I pursued my PhD. I would also like to thank the Department of Biology for its support and dedication. I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Kenneth Lacovara, for his guidance and patience. Additionally, I would like to thank him for including me in his pursuit of knowledge of Argentine dinosaurs and their environments. I am also indebted to my committee members, Dr. Gail Hearn, Dr. Jake Russell, Dr. Mike O‘Connor, Dr. Matthew Lamanna, Dr. Christopher Williams and Professor Hermann Pfefferkorn for their valuable comments and time. The support of Argentine scientists has been essential for allowing me to pursue my research. I am thankful that I had the opportunity to work with such kind and knowledgeable people. I would like to thank Dr. Fernando Novas (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales) for helping me obtain specimens that allowed this research to happen. I would also like to thank Dr. Viviana Barreda (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales) for her allowing me use of her lab space while I was visiting Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. -

Highly Diversified Late Cretaceous Fish Assemblage Revealed by Otoliths (Ripley Formation and Owl Creek Formation, Northeast Mississippi, Usa)

Rivista Italiana di Paleontologia e Stratigrafia (Research in Paleontology and Stratigraphy) vol. 126(1): 111-155. March 2020 HIGHLY DIVERSIFIED LATE CRETACEOUS FISH ASSEMBLAGE REVEALED BY OTOLITHS (RIPLEY FORMATION AND OWL CREEK FORMATION, NORTHEAST MISSISSIPPI, USA) GARY L. STRINGER1, WERNER SCHWARZHANS*2 , GEORGE PHILLIPS3 & ROGER LAMBERT4 1Museum of Natural History, University of Louisiana at Monroe, Monroe, Louisiana 71209, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Natural History Museum of Denmark, Zoological Museum, Universitetsparken 15, DK-2100, Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] 3Mississippi Museum of Natural Science, 2148 Riverside Drive, Jackson, Mississippi 39202, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 4North Mississippi Gem and Mineral Society, 1817 CR 700, Corinth, Mississippi, 38834, USA. E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author To cite this article: Stringer G.L., Schwarzhans W., Phillips G. & Lambert R. (2020) - Highly diversified Late Cretaceous fish assemblage revealed by otoliths (Ripley Formation and Owl Creek Formation, Northeast Mississippi, USA). Riv. It. Paleontol. Strat., 126(1): 111-155. Keywords: Beryciformes; Holocentriformes; Aulopiformes; otolith; evolutionary implications; paleoecology. Abstract. Bulk sampling and extensive, systematic surface collecting of the Coon Creek Member of the Ripley Formation (early Maastrichtian) at the Blue Springs locality and primarily bulk sampling of the Owl Creek Formation (late Maastrichtian) at the Owl Creek type locality, both in northeast Mississippi, USA, have produced the largest and most highly diversified actinopterygian otolith (ear stone) assemblage described from the Mesozoic of North America. The 3,802 otoliths represent 30 taxa of bony fishes representing at least 22 families. In addition, there were two different morphological types of lapilli, which were not identifiable to species level. -

Publications Related to Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Paleontology (All Featured Fossils in Publications Are Self-Collected.)

Publications Related to Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Paleontology (All featured fossils in publications are self-collected.) 1) Becker, M., Slattery, W., and Chamberlain, J., 1996, Reworked Campanian and Maastrichtian Macrofossils in a Sequence Bounding Transgressive Lag Deposit, Monmouth County, New Jersey, Northeast Geology and Environmental Science, Vol. 18, pp. 234-252. 2) Becker, M., Slattery, W., and Chamberlain, J., 1998, Mixing of Santonian and Campanian Chondrichthyan and Ammonite Macrofossils along a Transgressive Lag Deposit, Greene County, Western Alabama, Southeastern Geology, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 1-12. 3) Becker, M., Meier, J., and Slattery, W., 1999, Spiral Coprolites from the Upper Cretaceous Wenonah-Mt. Laurel and Navesink Formations in the Northern Coastal Plain of New Jersey, Northeastern Geology and Environmental Science, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 181-187. 4) Becker, M., Chamberlain, J., and Stoffer, P., 2000, Pathological Tooth Deformities in Modern and Late Cretaceous Chondrichthyans: A Consequence of Feeding Related Injury, Lethaia, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 1-16. 5) Becker, M., and Chamberlain, J., 2001, Fossil Turtles from the Lowermost Navesink Formation (Maastrichtian) in Monmouth County New Jersey, Northeastern Geology and Environmental Science, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 332-339. 6) Chamberlain, J., Terry, D., Stoffer, P., and Becker, M., 2001, Paleontology of the K/T Boundary: Badlands National Park, South Dakota; in Santucci, V. L. and McClelland, L., eds., Proceedings of the 6th Fossil Resource Conference: National Park Service Geological Resource Division Technical Report, pp. 11-22. 7) Becker, M., Earley R., and Chamberlain, J., 2002, A Survey of Non-Tooth Chondrichthyan Hard-Parts from the Lower Navesink Formation (Maastrichtian) in Monmouth County, New Jersey, Northeastern Geology and Environmental Science, Vol. -

Uppermost Campanian–Maestrichtian Strontium Isotopic, Biostratigraphic, and Sequence Stratigraphic Framework of the New Jersey Coastal Plain

Uppermost Campanian–Maestrichtian strontium isotopic, biostratigraphic, and sequence stratigraphic framework of the New Jersey Coastal Plain Peter J. Sugarman New Jersey Geological Survey, CN 427, Trenton, New Jersey 08625, and Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903 Kenneth G. Miller Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903, and Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 David Bukry U.S. Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Road, Menlo Park, California 94025 Mark D. Feigenson Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey 08903 ABSTRACT boundaries elsewhere in the Atlantic Recent stratigraphic studies have concen- Coastal Plain (Owens and Gohn, 1985) and trated on the relationships between these se- Firm stratigraphic correlations are the inferred global sea-level record of Haq quences, their bounding surfaces (unconfor- needed to evaluate the global significance of et al. (1987); they support eustatic changes mities), and related sea-level changes. The unconformity bounded units (sequences). as the mechanism controlling depositional shoaling-upward sequences described by We correlate the well-developed uppermost history of this sequence. However, the latest Owens and Sohl (1969) have been related to Campanian and Maestrichtian sequences Maestrichtian record in New Jersey does recent sequence stratigraphic terminology of the New Jersey Coastal Plain to the geo- not agree with Haq et al. (1987); we at- (e.g., Van Wagoner et al., 1988) by Olsson magnetic polarity time scale (GPTS) by in- tribute this to correlation and time-scale (1991) and Sugarman et al. (1993). Glauco- tegrating Sr-isotopic stratigraphy and bio- differences near the Cretaceous/Paleogene nite beds are equivalent to the condensed stratigraphy. -

Jason P. Schein

Curriculum Vitae JASON P. SCHEIN EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR BIGHORN BASIN PALEONTOLOGICAL INSTITUTE 3959 Welsh Road, Ste. 208 Willow Grove, Pennsylvania 19090 Office: (406) 998-1390 Cell: (610) 996-1055 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. Student Drexel University, Department of Biology, Earth and Environmental Science, 2005-2013 M.Sc., Auburn University, Department of Geology and Geography, 2004 B.Sc., Auburn University, Department of Geology and Geography, 2000 RESEARCH AND PROFESSIONAL INTERESTS Mesozoic vertebrate marine and terrestrial faunas, paleoecology, paleobiogeography, faunistics, taphonomy, biostratigraphy, functional morphology, sedimentology, general natural history, education and outreach, paleontological resource assessment, and entrepreneurial academic paleontology. ACADEMIC, PROFESSIONAL, & BOARD POSITIONS 2019-Present Member of the Board, Yellowstone-Bighorn Research Association 2017-Present Founding Executive Director, Bighorn Basin Paleontological Institute 2017-Present Member of the Board, Delaware Valley Paleontological Society 2016-Present Scientific and Educational Consultant, Field Station: Dinosaurs 2015-Present Graduate Research Associate, Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University 2007-2017 Assistant Curator of Natural History Collections and Exhibits, New Jersey State Museum 2015-2017 Co-founder, Co-leader, Bighorn Basin Dinosaur Project 2010-2015 International Research Associate, Palaeontology Research Team, University of Manchester 2010-2014 Co-leader, New Jersey State Museum’s Paleontology Field Camp 2007-2009 Interim Assistant Curator of Natural History, New Jersey State Museum 2006-2007 Manager, Dinosaur Hall Fossil Preparation Laboratory 2004-2005 Staff Environmental Geologist, Cobb Environmental and Technical Services, Inc. 1 FIELD EXPERIENCE 2010-2019 Beartooth Butte, Morrison, Lance, and Fort Union formations, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming and Montana, U.S.A. (Devonian, Jurassic, Late Cretaceous, and earliest Paleocene, respectively) 2010 Hell Creek Formation, South Dakota, U.S.A. -

Recent Mosasaur Discoveries from New Jersey and Delaware, USA: Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Implications for Mosasaur Extinction

r fs| Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 84 - 3 | 241 - 245 | 2005 Recent mosasaur discoveries from New Jersey and Delaware, USA: stratigraphy, taphonomy and implications for mosasaur extinction W.B. Gallagher1' 1 Bureau of Natural History, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ 08625-0530, USA. Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08855, USA. Manuscript received: December 2004; accepted: January 2005 Abstract The Upper Cretaceous deposits of New Jersey and Delaware produced the first mosasaur specimens collected in North America. Recent recovery of mosasaur specimens from streambank exposures and new excavation sites has increased our knowledge of the stratigraphic distribution of these animals in the northern Atlantic coastal plain. Reassessment of the source and age of mosasaur specimens from the Big Brook site and other localities in Monmouth County (NJ) has greatly increased the number of known Campanian mosasaur specimens from this region. Two main taphonomic occurrence modes are noted: 1 - single, worn and broken bones and isolated teeth in mixed faunal deposits probably accumulated due to current action in nearshore environments; 2 - partial skeletons, skulls and single bones in deeper-water settings were the aftermath of biological modification of carcasses and deadfalls. The mosasaurs of the New Egypt Formation represent some of the last (i.e., stratigraphically highest) mosasaur fossils in North America. Mosasaur extinction was due to the collapse of the rich Late Cretaceous marine food web at the K/T boundary. Subsequently in the early Paleocene, with the disappearance of the mosasaurs, crocodilians became the apical predators of the marine environment in this area. -

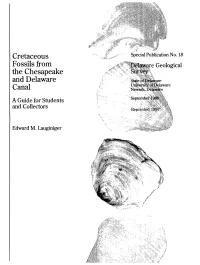

Cretaceous Fossils from the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal

Cretaceous S;cial Publication No. 18 Fossils from the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal A Guide for Students and Collectors Edward M. Lauginiger / /~ / CRETACEOUS FOSSILS FROM THE CHESAPEAKE AND DELAWARE CANAL: A GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AND COLLECTORS By Edward M. Lauginiger Biology Teacher Academy Park High School Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania September 1988 Reprinted 1997 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION. • 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 PREVIOUS STUDIES. 3 FOSSILS AND FOSSILIZATION 5 Requirements for Fossilization 6 Types of Fossilization 7 GEOLOGY •• 10 CLASSIFICATON OF FOSSILS. 12 Kingdom Monera • 13 Kindgom Protista 1 3 Kingdom Plantae. 1 4 Kingdom Animalia 15 Phylum Porifera 15 Phylum Cnidaria (Coelenterata). 16 Phylum Bryozoa. 16 Phylum Brachiopoda. 17 Phylum Mollusca • 18 Phylum Annelida •. 22 Phylum Arthropoda • 23 Phylum Echinodermata. 24 Phylum Chordata 24 COLLECTING LOCALITIES 28 FOSSIL CHECK LIST 30 BIBLIOGRAPHY. 33 PLATES. ••• 39 iii FIGURES Page Figure 1 • Index map of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal Area. .. .. 2 Figure 2. Generalized stratigraphic column of the formations exposed at the C & D Canal. 11 Figure 3. Foraminifera 14 Figure 4. Porifera 16 Figure 5. Cnidaria 16 Figure 6. Bryozoa. 17 Figure 7. Brachiopoda. 18 Figure 8. Mollusca-Gastropoda. 19 Figure 9. Mollusca-Pelecypoda. 21 Figure 10. Mollusca-Cephalopoda 22 Figure 11. Annelida . 22 Figure 12. Arthropoda 23 Figure 13. Echinodermata. 25 Figure 1 4. Chordata . 27 Figure 1 5. Collecting localities at the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal . ... .. 29 v CRETACEOUS FOSSILS FROM THE CHESAPEAKE AND DELAWARE CANAL: A GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AND COLLECTORS Edward M. Lauginiger INTRODUCTION Fossil collectors have been attracted to Delaware since the late 1820s when the excavation of the Chesapeake and Delaware (C&D) Canal first exposed marine fossils of Cretaceous age (Fig. -

PSEG POWER, LLC (Environmental Report), Rev. 0

Occurrence in Formation/Unit Primary Lithologies Geologic Conditions Unit Thickness Site Area Quaternary Marsh deposits muck and peat; silt, sand and clay aggradation of Delaware Bay estuary variable thickness present over most of the site area in low lying areas Holocene ~~~~~~~~~~ unconformity ~~~~~~~~~~ DELAWARE NEW JERSEY Scotts Corners Formation outcrops in eastern and Cape May estuarine terrace deposits with coarse to fine sand and pebbles with Quaternary ~~ unconformity ~~ transgressive and regressive cycles western portions of the site concentrations of heavy minerals; peat; isolated fluvial deposits? variable thickness Formation area Group Lynch Heights Pleistocene Delaware Bay Formation ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ unconformity ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ regression and erosion CENOZOIC 90 feet at southern portions Kirkwood Formation clay silt and sand deposited in two or three marine cycles polycyclic transgression and regression phases subcrop only of site area; pinches out northward Upper Tertiary (Miocene) ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ unconformity ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ regression and erosion Shark River Formation glauconitic sand and mudstone low sediment input 70 feet (Reference 2.6-10) subcrop only ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ unconformity ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ regression and erosion Tertiary Manasquan Formation lower glauconitic member; upper clayey sand to silt member low sediment input and bioturbation 40 feet (Reference 2.6-10) subcrop only ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ -

Short−Term Survival of Ammonites in New Jersey After the End−Cretaceous Bolide Impact

Short−term survival of ammonites in New Jersey after the end−Cretaceous bolide impact NEIL H. LANDMAN, MATTHEW P. GARB, REMY ROVELLI, DENTON S. EBEL, and LUCY E. EDWARDS Landman, N.H., Garb, M.P., Rovelli, R., Ebel, D.S., and Edwards, L.E. 2012. Short−term survival of ammonites in New Jersey after the end−Cretaceous bolide impact. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 57 (4): 703–715. A section containing the Cretaceous/Paleogene (= Cretaceous/Tertiary) boundary in Monmouth County, New Jersey, pre− serves a record of ammonites extending from the end of the Cretaceous into possibly the beginning of the Danian. The sec− tion includes the upper part of the Tinton Formation and lower part of the Hornerstown Formation. The top of the Tinton Formation is represented by a richly fossiliferous unit (the Pinna Layer) that contains many bivalves in life position as well as ammonite jaws preserved inside body chambers. Ammonites include Pachydiscus (Neodesmoceras) mokotibensis, Sphenodiscus lobatus, Eubaculites carinatus, E. latecarinatus, Discoscaphites iris, D. sphaeroidalis, D. minardi,andD. jerseyensis.ThePinna Layer probably represents a relatively short interval of time lasting tens to hundreds of years; it is conformably overlain by the Burrowed Unit, which contains a single fragment of Discoscaphites sp. and several fragments of E. latecarinatus, as well as several isolated specimens of ammonite jaws including two of Eubaculites. Examination of the mode of preservation of the ammonites and jaws suggests that they were fossilized during deposition of the Burrowed Unit and were not reworked from older deposits. Based on the ammonites and dinoflagellates in the Pinna Layer and the Burrowed Unit, these strata traditionally would be assigned to the uppermost Maastrichtian, corresponding to calcareous nannofossil Subzone CC26b. -

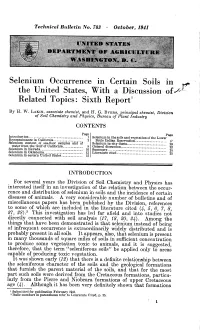

Selenium Occurrence in Certain Soils in the United States, with a Discussion Of- .R Related Topics: Sixth Report'

Technical Bulletin No. 783 ■ October, 1941 »»FAItT»f¿A|^«F,Atí»ÍClíl.l'«J«íl Selenium Occurrence in Certain Soils in the United States, With a Discussion of- .r Related Topics: Sixth Report' By H. W. LAKIN, associate chemist, and H. G. BYEKS, principal chemist, Division of Soil Chemistry and Physics, Bureau of Plant Industry CONTENTS Page lEtroduction 1 Selenium in the soils and vegetation of the Lower Reconnaissance in California 2 Brule Indian Reservation 17 Selenium content of sea-floor samples and of Selenium in city dusts 20 water from the Gulf of California 8 General discussion __ 22 Selenium in Nevada 10 Summary _._ 24 Selenium in Oklahoma 12 Literature cited '.'] 25 Selenium in eastern United States 15 INTRODUCTION For several years the Division of Soil Chemistry and Physics has interested itself in an investigation of the relation between the occur- rence and distribution of selenium in soils and the incidence of certain diseases of animals. A very considerable number of bulletins and of miscellaneous papers has been published by the Division, references to some of which are included in the hterature cited (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 27, 28)} This investigation has led far afield and into studies not directly connected with soil analysis {17, 18, 20, 24). Among the things that have been demonstrated is that selenium instead of being of infrequent occurrence is extraordinarily widely distributed and is probably present in all soils. It appears, also, that selenium is present in many thousands of square miles of soils in sufficient concentration to produce some vegetation toxic to animals, and it is suggested, therefore, that the term ''seleniferous soils'' be appHed only to areas capable of producing toxic vegetation. -

Stratigraphy, Taphonomy and Implications for Mosasaur Extinction

r fs| Netherlands Journal of Geosciences — Geologie en Mijnbouw | 84 - 3 | 241 - 245 | 2005 Recent mosasaur discoveries from New Jersey and Delaware, USA: stratigraphy, taphonomy and implications for mosasaur extinction W.B. Gallagher1' 1 Bureau of Natural History, New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, NJ 08625-0530, USA. Email: [email protected] 2 Department of Geological Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08855, USA. Manuscript received: December 2004; accepted: January 2005 Abstract The Upper Cretaceous deposits of New Jersey and Delaware produced the first mosasaur specimens collected in North America. Recent recovery of mosasaur specimens from streambank exposures and new excavation sites has increased our knowledge of the stratigraphic distribution of these animals in the northern Atlantic coastal plain. Reassessment of the source and age of mosasaur specimens from the Big Brook site and other localities in Monmouth County (NJ) has greatly increased the number of known Campanian mosasaur specimens from this region. Two main taphonomic occurrence modes are noted: 1 - single, worn and broken bones and isolated teeth in mixed faunal deposits probably accumulated due to current action in nearshore environments; 2 - partial skeletons, skulls and single bones in deeper-water settings were the aftermath of biological modification of carcasses and deadfalls. The mosasaurs of the New Egypt Formation represent some of the last (i.e., stratigraphically highest) mosasaur fossils in North America. Mosasaur extinction was due to the collapse of the rich Late Cretaceous marine food web at the K/T boundary. Subsequently in the early Paleocene, with the disappearance of the mosasaurs, crocodilians became the apical predators of the marine environment in this area.