The Thailand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Despatches Summer 2016 July 2016

Summer 2016 www.gbg-international.com DESPATCHES IN THIS ISSUE: PLUS Battlefield Guide On The River Kwai Verdun 1916 - The Longest Battle The Ardennes and Back Again AND Roman Guides Guide Books 02 | Despatches FIELD guides Our cover image: Dr John Greenacre brushing up on the facts at the Sittang River, Myanmar. Andrew Thomson explaining the Siegfried Line, Hurtgen Forest, Germany German trenches in the Bois d’Apremont, St Mihiel. www.gbg-international.com | 03 Contents P2 FIELD guides P18-20 TESTING THE TESTUDO A Guild project P5-11 HELP FOR HEROES IN THAILAND P21 FIELD guides AND MYANMAR An Opportunity Grasped P22-25 VERDUN The Longest Battle P12-16 A TALE OF TWO TOURS Two different perspectives P25 EVENT guide 2016 P17 FIELD guides P26-27 GUIDE books Under The Devil’s Eye, newly joined Associate Member, Alan Wakefield explaining the intricacies of The Birdcage Line outside Thessaloniki. (Picture StaffRideUK) 04 | Despatches OPENING shot: THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW Welcome fellow members, Guild Partners, and positive. The cream will rise to the top and those at the Supporters to the Summer 2016 edition of fore of our trade will take those that want to raise their Despatches, the house magazine of the Guild. individual and collective standards with them. These The year so far has been dominated by FWW interesting times offer great opportunities for the commemorative events marking the centenaries of Guild. Our validation programme is an ideal vehicle Jutland, Verdun and the Somme. Recent weeks have for those seeking self-improvement and, coupled with seen the predominantly Australian ceremonies at our shared aims, encourages the raising of collective Fromelles and Pozieres. -

E&O Fact Sheet.Pub

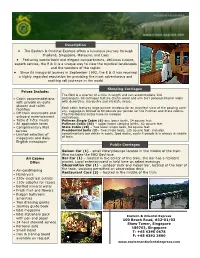

Description • The Eastern & Oriental Express offers a luxurious journey through Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Laos • Featuring comfortable and elegant compartments, delicious cuisine, superb service, the E & O is a unique way to view the mystical landscapes and the wonders of the region • Since its inaugural journey in September 1993, the E & O has received a highly regarded reputation for providing the most adventurous and exciting rail journeys in the world Sleeping Carriages Prices Include: The E&O is a quarter of a mile in length and can accommodate 126 • Cabin accommodations passengers. All carriages feature cherry wood and elm burr paneled interior walls with private en-suite with decorative marquetry and intricate inlays. shower and toilet Each cabin features large picture windows for an excellent view of the passing scen- facilities ery. Luggage is limited to 60 pounds per person for the Pullman and State cabins. • Off train excursions and The Presidential suites have no luggage onboard entertainment restrictions. • Table d’ hôte meals Pullman Single Cabin (6) -one lower berth, 54 square feet • All applicable taxes Pullman Cabin (30) – upper/lower sleeping births, 62 square feet • Complimentary Mail State Cabin (28) – Two lower single beds, 84 square feet service Presidential Suite (2) – Two single beds, 125 square feet. Includes • Limited selection of complimentary bar drinks in cabin, Ipod docks, seats 4 people & is always in middle magazines and daily of train. English newspaper Public Carriages Saloon Car (1) - small library/lounge located in the middle of the train. Also includes the E&O Boutique All Cabins Bar Car (1) – located in the center of the train, the bar has a resident Offer: pianist. -

“The Bridge on the River Kwai”

52 วารสารมนุษยศาสตร์ ฉบับบัณฑิตศึกษา “The Bridge on the River Kwai” - Memory Culture on World War II as a Product of Mass Tourism and a Hollywood Movie Felix Puelm1 Abstract During World War II the Japanese army built a railway that connected the countries of Burma and Thailand in order to create a safe supply route for their further war campaigns. Many of the Allied prisoners of war (PoWs) and the Asian laborers that were forced to build the railway died due to dreadful living and working conditions. After the war, the events of the railway’s construction and its victims were mostly forgotten until the year 1957 when the Oscar- winning Hollywood movie “The Bridge on the River Kwai” visualized this tragedy and brought it back into the public memory. In the following years western tourists arrived in Kanchanaburi in large numbers, who wanted to visit the locations of the movie. In order to satisfy the tourists’ demands a diversified memory culture developed often ignoring historical facts and geographical circumstances. This memory culture includes commercial and entertaining aspects as well as museums and war cemeteries. Nevertheless, the current narrative presents the Allied prisoners of war at the center of attention while a large group of victims is set to the outskirts of memory. Keywords: World War II, Memory Culture, Kanchanaburi, River Kwai, Japanese Atrocities Introduction Kanchanaburi in western Thailand has become an internationally well-known symbol of World War II in Southeast Asia and the Japanese atrocities. Every year more than 4 million tourists are attracted by the historical sites. At the center of attention lies a bridge that was once part of the Thailand-Burma Railway, built by the Japanese army during the war. -

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Bangkok Program Concludes in: Singapore Available on these Sailings: 11-Apr-2020 Selling price from: Please call to discuss cabin options and pricing Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Board the Eastern & Oriental Express and journey from Bangkok to Singapore in true classic fashion. Begin with a few days amid the ornate shrines and vibrant streets of the Thai capital. Then, it’s all aboard for a ride that will remain in your heart forever. Along the way, you’ll savor gourmet cuisine and enjoy a host of possibilities—from touring rice paddies and participating in a local cooking class, trekking through the Malaysian hills. Discover the cultural riches and natural beauty of Asia on a tour that gives you plenty of ways to embrace them both. Many nationals, including US and UK citizens, do not require a visa to enter Thailand or Singapore. Please check with your travel professional or directly with the Thai Embassy to confirm your specific travel document requirements. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. Passport should have at least 6 months validity at the time of travel. Sales of this program close 90 days prior; book early to avoid disappointment, as space is limited. HIGHLIGHTS: ● Bangkok: Enjoy a guided tour that visits the Grand Palace and famed Reclining Buddha. ● Eastern & Oriental Express: Spend three nights on this luxurious train, stopping along the way to discover the wonders of Asia. Savor daily four-course dinners and three-course lunches. -

Notes on the Thai-Burma Railway Part ⅰ : "The Bridge on the River Kwai"-The Movie

- 112 - NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅰ : "THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI"-THE MOVIE Ⅰ David Boggett Ⅱ Map of the Thai-Burma Railway Kanchanaburi (Kanburi) area. The dotted line indicates the route proposed by the original (British) survey. 京都精華大学紀要 第十九号 - 113 - - 114 - NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅰ : "THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI"-THE MOVIE () () () (1)"The Bridge on the River Kwai." (2)The end of the line today: Nam Tok Station(Tarsao). (3)Japanese-built SL for the Thai-Burma Railway, preserved at the Kwae Bridge. The locomotive was abandonned, concealed in a bomb-proof railway siding in a cave near Sangklaburi. It was discovered by a group of Australians in 1970 using an old Japanese map. (4)Today's train slowly edges round the perilous Tham Krasae (Wampo) viaduct. () 京都精華大学紀要 第十九号 - 115 - () (5)The Three Pagoda Pass where the railway crossed the Thailand-Burma border. (6)Cutting on the Konyu-Hintok section of the Railway. Preserved -

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country Starter Pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a Glance

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country starter pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a glance POPULATION - 2014 GNI PER CAPITA (PPP) - 2014* US$13,950 68.7 INCOME LEVEL million Upper middle *Gross National Income (Purchasing Power Parity) World Bank GDP GROWTH 2014 CAPITAL CITY 1% GDP GROWTH FORECAST (IMF) 3.7% (2015), 3.9% (2016), 4% (2017) Bangkok RELIGION CLIMATE CURRENCY FISCAL YEAR jan-dec Buddhism (90%) 3 distinct seasons THAI BAHT (THB) calendar year SUMMER, RAINY, COOL > TIME DIFFERENCE AUSTRALIAN IMPORTS AUSTRALIAN EXPORTS EXCHANGE RATE TO BANGKOK (ICT) FROM THAILAND (2014) TO THAILAND (2014) (2014 AVERAGE) 3 hours A$10.94 A$5.17 ( THB/AUD) behind (AEST) Billion Billion A$1 = THB 29.3 SURFACE AREA Contents 513,115 1. Introduction to Thailand 4 1.1 Why Thailand? 5 square kmS Opportunities for Australian businesses 1.2 Thailand overview 8 1.3 Thailand and Australia: the bilateral relationship 16 GDP 2014 2. Getting started in Thailand 20 2.1 What you need to consider 22 2.2 Researching Thailand 32 US$387.3 billion 2.3 Possible business structures 34 2.4 Manufacturing in Thailand 37 3. Sales & marketing in Thailand 40 POLITICAL STRUCTURE 3.1 Direct exporting 42 3.2 Franchising 44 Constitutional 3.3 Licensing 46 3.4 Online sales 46 Monarchy 3.5 Marketing 46 3.6 Labelling requirements 47 GENERAL BANKING HOURS 4. Conducting business in Thailand 48 4.1 Thai culture and business etiquette 49 Monday to Friday 4.2 Building relationships with Thais 53 4.3 Negotiations and meetings 54 9:30AM to 3:30PM 4.4 Due diligence and avoiding scams 56 5. -

But with the Defeat of the Japanese (The Railway) Vanished Forever and Only the Most Lurid Wartime Memories and Stories Remain

-104- NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅳ: "AN APPALLING MASS CRIME" But with the defeat of the Japanese (the railway) vanished forever and only the most lurid wartime memories and stories remain. The region is once again a wilderness, except for a few neatly kept graveyards where many British dead now sleep in peace and dignity. As for the Asians who died there, both Burmese and Japanese, their ashes lie scattered and lost and forgotten forever. - Ba Maw in his diary, "Breakthrough In Burma" (Yale University, 1968). To get the job done, the Japanese had mainly human flesh for tools, but flesh was cheap. Later there was an even more plentiful supply of native flesh - Burmese, Thais, Malays, Chinese, Tamils and Javanese - ..., all beaten, starved, overworked and, when broken, thrown carelessly on that human rubbish-heap, the Railway of Death. -Ernest Gordon, former British POW, in his book, "Miracle on the River Kwai" (Collins, 1963). The Sweat Army, one of the biggest rackets of the Japanese interlude in Burma is an equivalent of the slave labour of Nazi Germany. It all began this way. The Japanese needed a land route from China to Malaya and Burma, and Burma as a member or a future member of the Co-prosperity Sphere was required to contribute her share in the construction of the Burma-Thailand (Rail) Road.... The greatest publicity was given to the labour recruitment campaign. The rosiest of wage terms and tempting pictures of commodities coming in by way of Thailand filled the newspapers. Special medical treatment for workers and rewards for those remaining at home were publicised. -

CODE NC302: 3 Days 2 Nights RIVER KWAI Nature & Culture

CODE NC302: 3 days 2 nights RIVER KWAI Nature & Culture Highlight: Thailand–Burma Railway Centre, War Cemetery, River Kwai Bridge, Hellfire Pass Memorial, Mon Tribal Village & Temple, Elephant Ride, Bamboo Rafting and Death Railway Train. Day 1 - / L / D Thailand–Burma Railway Centre 06.00-06.30 Pick up from major hotel in Bangkok downtown area. Depart to Kanchanaburi province (128 km. to the west of Bangkok) 09.00 Arrive Kanchanaburi province Visit Thailand–Burma Railway Centre an interactive museum, information and research facility dedicated to presenting the history of the Thailand-Burma Railway. The fully air-conditioned center offers the visitor an educational and moving experience Allied War Cemetery Visit Allied War Cemetery which is memorial to some 6000 allied prisoners of war (POWs) who perished along the death railway line and were moved post-war to this eternal resting place. Visit the world famous Bridge over the River Kwai, a part of Death Railway constructed by Allied POWs. 12.00 Take a long–tailed boat on River Kwai to River Kwai Jungle Rafts. Check–in and have Lunch upon arrival. 14.45 Take a long-tailed boat ride downstream to Resotel Pier and continue on Bridge over the River Kwai road to visit the Hellfire Pass Memorial. Then return to the rafts 19.00 Dinner followed by a 45–minute presentation of traditional Mon Dance and overnight at the River Kwai Jungle Rafts. Day 2 B / L / D 07.00 Breakfast. 09.00 Visit nearby ethnic Mon Tribal village & Temple and Elephant Ride River Kwai Jungle Rafts through bamboo forest. -

The Road Into Burma from Thailand Into Myanmar 25

THE ROAD INTO BURMA FROM THAILAND INTO MYANMAR 25 FEBRUARY TO 19 MARCH 2017 THE ROAD INTO BURMA Modern Burma offers us a series of contradictions and makes a fascinating country to visit. We will enter the country close to the route of the ‘Burma Railway’, the name given to the railway access from Thailand constructed under the Japanese during the Second World War by prison- ners of war, with terrible loss of life. We will visit some of the war graves, as well as the bridge over the River Kwai. In Moulmein we will see the stupa celebrated in Kipling’s poem The Road to Mandalay. In Yangon, former Rangoon, and colonial capital, a number of interesting early 20th century buildings have survived which make for a good city walk. In Bagan, a landscape filled with stupas amongst the acacia trees is one of the most extraordinary sights imaginable: during the medieval period it’s been calculated that a new stupa was erected every few weeks. The tran- sition, in recent years, from military dictatorship to democracy has had us all rivetted: we have witnessed the extraordinary tenacity of Aung San Suu Kyi as she has gone from political prisoner, Nobel prize winner, to elected politician. Our journey through the country continues to the very peaceful lake at Inle. Here our hotel is raised on stilts over the lake water. We will travel to Man- dalay, whose heart is formed by a huge moated palace. In the hills above the city is the colonial summer capital at Pyin Oo Lwin, complete with clocktower, botanical gardens and half timbered houses. -

Eastern&Oriental Express

Reserve your Bangkok to Bali trip today! NOT INCLUDED-Fees for passports and, if applicable, visas, entry/departure fees; personal gratuities; laundry and dry cleaning; excursions, wines, liquors, mineral waters and Dear Duke Alumni and Friends, Trip #:10-22214W meals not mentioned in this brochure under included fea- | INCLUDED FEATURES | tures; travel insurance; all items of a strictly personal nature. LAND PROGRAM Send to: Eastern & Oriental Express MOBILITY AND FITNESS TO TRAVEL-The right is retained to Join us on the journey of a lifetime as we explore Thailand, “To travel by train is Duke Alumni Travel decline to accept or to retain any person as a member of this October 8-18, 2016 ACCOMMODATIONS trip who, in the opinion of AHI Travel is unfit for travel or Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia. On this 10-night adventure, take in Paid P.O. Box 90572 to see nature and Durham, NC 27708-0572 whose physical or mental condition may constitute a danger to themselves or to others on the trip, subject only to the • Three nights in Bangkok, Thailand, at jaw-dropping tropical scenery from the refined Eastern & Oriental AHI Travel Phone: 800-FOR-DUKE Travel Fax: 919-660-0148 Postage U.S. requirement that the portion of the total amount paid which human beings, towns Std. Presorted corresponds to the unused services and accommodations be Special Price* The Peninsula Bangkok, a deluxe hotel. Please contact Duke Alumni Travel at 800-367-3853 to reserve your space or refunded. Passengers requiring special assistance, including Full Price Special Savings Express, ride tuk-tuks through colorful Bangkok and float down the AHI Travel 855-385-3885 with questions. -

Opportunities for British Companies in Burma's Infrastructure Sector

Opportunities for British companies in Burma’s Infrastructure sector 2 Opportunities for British companies in Burma’s Infrastructure sector Opportunities for British companies in Burma’s Infrastructure sector 3 Contents Executive summary p. 4 Company profile p. 5 Macroeconomic and business environment in Burma p. 6 Aviation sector p. 14 Road p. 22 Rail p. 31 Ports p. 39 Industrial p. 46 Energy P. 54 4 Opportunities for British companies in Burma’s Infrastructure sector Executive Summary There are few countries in today’s Higher incomes and relaxed rules Industrial production is becoming world that are changing as rapidly have led to a surge in car and an important economic driver, as Burma. Its economy is expanding motorbike ownership, with over five as Burma’s political transition by some of the highest rates in the million vehicles now registered. The inspires renewed confidence in its world, while politically the country road network is being quickly built economic production. Development has undergone a bold transition up to handle the increase in vehicle of industrial zones and special towards democracy in just a few numbers, and neighbouring countries economic zones will continue to be years. New businesses are opening, are keen to extend international important as companies look for and incomes are rising. The highways through Burma to improve locations for their businesses. population is young and dynamic, regional transportation. and Burma is strategically located Powering Burma is a major challenge. between China, India and ASEAN, The domestic railway network is the Officials have stated an aim to move three important centres of growth longest among the ten Southeast from roughly 35% electrification in the 21st century. -

Thailand Sears Eldredge Macalester College

Macalester College DigitalCommons@Macalester College Book Chapters Captive Audiences/Captive Performers 2014 Chapter 2. "Jungle Shows" Thailand Sears Eldredge Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks Recommended Citation Eldredge, Sears, "Chapter 2. "Jungle Shows" Thailand" (2014). Book Chapters. Book 20. http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/thdabooks/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Captive Audiences/Captive Performers at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 48 Chapter 2: “Jungle Shows” Thailand Those jungle shows striving to create laughter amid exhaustion and cruelty. Jimmy Walker, Of Rice and Men 1942 Up Country The first POWs from Changi POW Camp, Singapore, were sent Up Country to Thailand during the monsoon season in mid-June 1942 as “Mainland No. 1 Work Party”—an advance group whose job was to assist the I. J. A. engineers in surveying the route of the projected railway and to build the supply depot at Nong Pladuk/000 Kilo, the transit camp at Ban Pong/003 Kilo, and the first leg of the railway to the Kanchanaburi area. It wasn’t until October, when the monsoon season was drawing to a close, that thousands of POWs followed, crammed into steel boxcars like so much chattel for the train trip north. FIGURE 2.1. “SINGAPORE—BANGKOK.” JACK CHALKER. COURTESY OF JACK CHALKER. “The next stage of our journey, to be repeated every day,” Laurie Allisoni remembered, “was sheer hell with shortage of water, shortage of food, jammed stinking bodies and short tempers.