Secrets & Spies Research Dossier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Despatches Summer 2016 July 2016

Summer 2016 www.gbg-international.com DESPATCHES IN THIS ISSUE: PLUS Battlefield Guide On The River Kwai Verdun 1916 - The Longest Battle The Ardennes and Back Again AND Roman Guides Guide Books 02 | Despatches FIELD guides Our cover image: Dr John Greenacre brushing up on the facts at the Sittang River, Myanmar. Andrew Thomson explaining the Siegfried Line, Hurtgen Forest, Germany German trenches in the Bois d’Apremont, St Mihiel. www.gbg-international.com | 03 Contents P2 FIELD guides P18-20 TESTING THE TESTUDO A Guild project P5-11 HELP FOR HEROES IN THAILAND P21 FIELD guides AND MYANMAR An Opportunity Grasped P22-25 VERDUN The Longest Battle P12-16 A TALE OF TWO TOURS Two different perspectives P25 EVENT guide 2016 P17 FIELD guides P26-27 GUIDE books Under The Devil’s Eye, newly joined Associate Member, Alan Wakefield explaining the intricacies of The Birdcage Line outside Thessaloniki. (Picture StaffRideUK) 04 | Despatches OPENING shot: THE CHAIRMAN’S VIEW Welcome fellow members, Guild Partners, and positive. The cream will rise to the top and those at the Supporters to the Summer 2016 edition of fore of our trade will take those that want to raise their Despatches, the house magazine of the Guild. individual and collective standards with them. These The year so far has been dominated by FWW interesting times offer great opportunities for the commemorative events marking the centenaries of Guild. Our validation programme is an ideal vehicle Jutland, Verdun and the Somme. Recent weeks have for those seeking self-improvement and, coupled with seen the predominantly Australian ceremonies at our shared aims, encourages the raising of collective Fromelles and Pozieres. -

E&O Fact Sheet.Pub

Description • The Eastern & Oriental Express offers a luxurious journey through Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia, and Laos • Featuring comfortable and elegant compartments, delicious cuisine, superb service, the E & O is a unique way to view the mystical landscapes and the wonders of the region • Since its inaugural journey in September 1993, the E & O has received a highly regarded reputation for providing the most adventurous and exciting rail journeys in the world Sleeping Carriages Prices Include: The E&O is a quarter of a mile in length and can accommodate 126 • Cabin accommodations passengers. All carriages feature cherry wood and elm burr paneled interior walls with private en-suite with decorative marquetry and intricate inlays. shower and toilet Each cabin features large picture windows for an excellent view of the passing scen- facilities ery. Luggage is limited to 60 pounds per person for the Pullman and State cabins. • Off train excursions and The Presidential suites have no luggage onboard entertainment restrictions. • Table d’ hôte meals Pullman Single Cabin (6) -one lower berth, 54 square feet • All applicable taxes Pullman Cabin (30) – upper/lower sleeping births, 62 square feet • Complimentary Mail State Cabin (28) – Two lower single beds, 84 square feet service Presidential Suite (2) – Two single beds, 125 square feet. Includes • Limited selection of complimentary bar drinks in cabin, Ipod docks, seats 4 people & is always in middle magazines and daily of train. English newspaper Public Carriages Saloon Car (1) - small library/lounge located in the middle of the train. Also includes the E&O Boutique All Cabins Bar Car (1) – located in the center of the train, the bar has a resident Offer: pianist. -

“The Bridge on the River Kwai”

52 วารสารมนุษยศาสตร์ ฉบับบัณฑิตศึกษา “The Bridge on the River Kwai” - Memory Culture on World War II as a Product of Mass Tourism and a Hollywood Movie Felix Puelm1 Abstract During World War II the Japanese army built a railway that connected the countries of Burma and Thailand in order to create a safe supply route for their further war campaigns. Many of the Allied prisoners of war (PoWs) and the Asian laborers that were forced to build the railway died due to dreadful living and working conditions. After the war, the events of the railway’s construction and its victims were mostly forgotten until the year 1957 when the Oscar- winning Hollywood movie “The Bridge on the River Kwai” visualized this tragedy and brought it back into the public memory. In the following years western tourists arrived in Kanchanaburi in large numbers, who wanted to visit the locations of the movie. In order to satisfy the tourists’ demands a diversified memory culture developed often ignoring historical facts and geographical circumstances. This memory culture includes commercial and entertaining aspects as well as museums and war cemeteries. Nevertheless, the current narrative presents the Allied prisoners of war at the center of attention while a large group of victims is set to the outskirts of memory. Keywords: World War II, Memory Culture, Kanchanaburi, River Kwai, Japanese Atrocities Introduction Kanchanaburi in western Thailand has become an internationally well-known symbol of World War II in Southeast Asia and the Japanese atrocities. Every year more than 4 million tourists are attracted by the historical sites. At the center of attention lies a bridge that was once part of the Thailand-Burma Railway, built by the Japanese army during the war. -

Issue125 – Jan 2016

CASCABEL Journal of the ROYAL AUSTRALIAN ARTILLERY ASSOCIATION (VICTORIA) INCORPORATED ABN 22 850 898 908 ISSUE 125 Published Quarterly in JANUARY 2016 Victoria Australia Russian 6 inch 35 Calibre naval gun 1877 Refer to the Suomenlinna article on #37 Article Pages Assn Contacts, Conditions & Copyright 3 The President Writes & Membership Report 5 From The Colonel Commandant + a message from the Battery Commander 6 From the Secretary’s Table 7 A message from the Battery Commander 2/10 Light Battery RAA 8 Letters to the Editor 11 Tradition Continues– St Barbara’s Day Parade 2015 (Cont. on page 51) 13 My trip to the Western Front. 14 Saint Barbara’s Day greeting 15 RAA Luncheon 17 Broome’s One Day War 18 First to fly new flag 24 Inspiring leadership 25 Victoria Cross awarded to Lance Corporal for Afghanistan rescue 26 CANADIAN tribute to the results of PTSD. + Monopoly 27 Skunk: A Weapon From Israel + Army Remembrance Pin 28 African pouched rats 29 Collections of engraved Zippo lighters 30 Flying sisters take flight 31 A variety of links for your enjoyment 32 New grenade launcher approved + VALE Luke Worsley 33 Defence of Darwin Experience won a 2014 Travellers' Choice Award: 35 Two Hundred and Fifty Years of H M S Victory 36 Suomenlinna Island Fortress 37 National Gunner Dinner on the 27th May 2017. 38 WHEN is a veteran not a war veteran? 39 Report: British Sniper Saves Boy, Father 40 14th Annual Vivian Bullwinkel Oration 41 Some other military reflections 42 Aussies under fire "like rain on water" in Afghan ambush 45 It’s something most of us never hear / think much about.. -

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre

Rail & Sail Asia Eastern & Oriental Express 6-Night Pre-voyage Land Journey Program Begins in: Bangkok Program Concludes in: Singapore Available on these Sailings: 11-Apr-2020 Selling price from: Please call to discuss cabin options and pricing Call 1-855-AZAMARA to reserve your Land Journey Board the Eastern & Oriental Express and journey from Bangkok to Singapore in true classic fashion. Begin with a few days amid the ornate shrines and vibrant streets of the Thai capital. Then, it’s all aboard for a ride that will remain in your heart forever. Along the way, you’ll savor gourmet cuisine and enjoy a host of possibilities—from touring rice paddies and participating in a local cooking class, trekking through the Malaysian hills. Discover the cultural riches and natural beauty of Asia on a tour that gives you plenty of ways to embrace them both. Many nationals, including US and UK citizens, do not require a visa to enter Thailand or Singapore. Please check with your travel professional or directly with the Thai Embassy to confirm your specific travel document requirements. All Passport details should be confirmed at the time of booking. Passport should have at least 6 months validity at the time of travel. Sales of this program close 90 days prior; book early to avoid disappointment, as space is limited. HIGHLIGHTS: ● Bangkok: Enjoy a guided tour that visits the Grand Palace and famed Reclining Buddha. ● Eastern & Oriental Express: Spend three nights on this luxurious train, stopping along the way to discover the wonders of Asia. Savor daily four-course dinners and three-course lunches. -

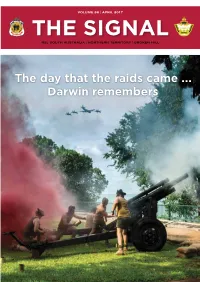

The Day That the Raids Came ... Darwin Remembers RSL CARE SA

VOLUME 86 | APRIL 2017 R E T E U U R G N A E E D L & SERVICES A F F I LI AT E RSL SOUTH AUSTRALIA | NORTHERN TERRITORY | BROKEN HILL The day that the raids came ... Darwin remembers RSL CARE SA RSL Care SA, providing a range of care and support services for the ex-service and veteran community. RSL Care SA has extensive experience and understanding of DVA and the implications of DVA entitlements entering residential aged care. For many people, considering nursing home aged care can be a stressful time. Our friendly admissions team is available to help guide you through the process and answer questions you may have. The Australian Government has strong protections in place to ensure that care is affordable for everyone and also subsidises a range of aged care services in Australia. Our nursing homes or residential aged care facilities offer short-term respite care or permanent care options. RSL Care SA has care facilities in Myrtle Bank and Angle Park. The War Veterans’ Home (WVH) is located in Myrtle Bank only 4kms from the CBD and is home to 95 residents. RSL Villas are situated next to Remembrance Park in Angle Park, 9kms north-west of the city. If you would like more information regarding residential aged care, the implications of DVA payments in aged care or to be considered for a place in one of our facilities, please call our admissions team on 08 8379 2600. For more information visit our website www.rslcaresa.com.au or www.myagedcare.gov.au War Veterans’ Home RSL Villas 55 Ferguson Avenue, Myrtle Bank SA 5064 18 Trafford Street, -

Notes on the Thai-Burma Railway Part ⅰ : "The Bridge on the River Kwai"-The Movie

- 112 - NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅰ : "THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI"-THE MOVIE Ⅰ David Boggett Ⅱ Map of the Thai-Burma Railway Kanchanaburi (Kanburi) area. The dotted line indicates the route proposed by the original (British) survey. 京都精華大学紀要 第十九号 - 113 - - 114 - NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅰ : "THE BRIDGE ON THE RIVER KWAI"-THE MOVIE () () () (1)"The Bridge on the River Kwai." (2)The end of the line today: Nam Tok Station(Tarsao). (3)Japanese-built SL for the Thai-Burma Railway, preserved at the Kwae Bridge. The locomotive was abandonned, concealed in a bomb-proof railway siding in a cave near Sangklaburi. It was discovered by a group of Australians in 1970 using an old Japanese map. (4)Today's train slowly edges round the perilous Tham Krasae (Wampo) viaduct. () 京都精華大学紀要 第十九号 - 115 - () (5)The Three Pagoda Pass where the railway crossed the Thailand-Burma border. (6)Cutting on the Konyu-Hintok section of the Railway. Preserved -

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country Starter Pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a Glance

Thailand COUNTRY STARTER PACK Country starter pack 2 Introduction to Thailand Thailand at a glance POPULATION - 2014 GNI PER CAPITA (PPP) - 2014* US$13,950 68.7 INCOME LEVEL million Upper middle *Gross National Income (Purchasing Power Parity) World Bank GDP GROWTH 2014 CAPITAL CITY 1% GDP GROWTH FORECAST (IMF) 3.7% (2015), 3.9% (2016), 4% (2017) Bangkok RELIGION CLIMATE CURRENCY FISCAL YEAR jan-dec Buddhism (90%) 3 distinct seasons THAI BAHT (THB) calendar year SUMMER, RAINY, COOL > TIME DIFFERENCE AUSTRALIAN IMPORTS AUSTRALIAN EXPORTS EXCHANGE RATE TO BANGKOK (ICT) FROM THAILAND (2014) TO THAILAND (2014) (2014 AVERAGE) 3 hours A$10.94 A$5.17 ( THB/AUD) behind (AEST) Billion Billion A$1 = THB 29.3 SURFACE AREA Contents 513,115 1. Introduction to Thailand 4 1.1 Why Thailand? 5 square kmS Opportunities for Australian businesses 1.2 Thailand overview 8 1.3 Thailand and Australia: the bilateral relationship 16 GDP 2014 2. Getting started in Thailand 20 2.1 What you need to consider 22 2.2 Researching Thailand 32 US$387.3 billion 2.3 Possible business structures 34 2.4 Manufacturing in Thailand 37 3. Sales & marketing in Thailand 40 POLITICAL STRUCTURE 3.1 Direct exporting 42 3.2 Franchising 44 Constitutional 3.3 Licensing 46 3.4 Online sales 46 Monarchy 3.5 Marketing 46 3.6 Labelling requirements 47 GENERAL BANKING HOURS 4. Conducting business in Thailand 48 4.1 Thai culture and business etiquette 49 Monday to Friday 4.2 Building relationships with Thais 53 4.3 Negotiations and meetings 54 9:30AM to 3:30PM 4.4 Due diligence and avoiding scams 56 5. -

But with the Defeat of the Japanese (The Railway) Vanished Forever and Only the Most Lurid Wartime Memories and Stories Remain

-104- NOTES ON THE THAI-BURMA RAILWAY PART Ⅳ: "AN APPALLING MASS CRIME" But with the defeat of the Japanese (the railway) vanished forever and only the most lurid wartime memories and stories remain. The region is once again a wilderness, except for a few neatly kept graveyards where many British dead now sleep in peace and dignity. As for the Asians who died there, both Burmese and Japanese, their ashes lie scattered and lost and forgotten forever. - Ba Maw in his diary, "Breakthrough In Burma" (Yale University, 1968). To get the job done, the Japanese had mainly human flesh for tools, but flesh was cheap. Later there was an even more plentiful supply of native flesh - Burmese, Thais, Malays, Chinese, Tamils and Javanese - ..., all beaten, starved, overworked and, when broken, thrown carelessly on that human rubbish-heap, the Railway of Death. -Ernest Gordon, former British POW, in his book, "Miracle on the River Kwai" (Collins, 1963). The Sweat Army, one of the biggest rackets of the Japanese interlude in Burma is an equivalent of the slave labour of Nazi Germany. It all began this way. The Japanese needed a land route from China to Malaya and Burma, and Burma as a member or a future member of the Co-prosperity Sphere was required to contribute her share in the construction of the Burma-Thailand (Rail) Road.... The greatest publicity was given to the labour recruitment campaign. The rosiest of wage terms and tempting pictures of commodities coming in by way of Thailand filled the newspapers. Special medical treatment for workers and rewards for those remaining at home were publicised. -

CODE NC302: 3 Days 2 Nights RIVER KWAI Nature & Culture

CODE NC302: 3 days 2 nights RIVER KWAI Nature & Culture Highlight: Thailand–Burma Railway Centre, War Cemetery, River Kwai Bridge, Hellfire Pass Memorial, Mon Tribal Village & Temple, Elephant Ride, Bamboo Rafting and Death Railway Train. Day 1 - / L / D Thailand–Burma Railway Centre 06.00-06.30 Pick up from major hotel in Bangkok downtown area. Depart to Kanchanaburi province (128 km. to the west of Bangkok) 09.00 Arrive Kanchanaburi province Visit Thailand–Burma Railway Centre an interactive museum, information and research facility dedicated to presenting the history of the Thailand-Burma Railway. The fully air-conditioned center offers the visitor an educational and moving experience Allied War Cemetery Visit Allied War Cemetery which is memorial to some 6000 allied prisoners of war (POWs) who perished along the death railway line and were moved post-war to this eternal resting place. Visit the world famous Bridge over the River Kwai, a part of Death Railway constructed by Allied POWs. 12.00 Take a long–tailed boat on River Kwai to River Kwai Jungle Rafts. Check–in and have Lunch upon arrival. 14.45 Take a long-tailed boat ride downstream to Resotel Pier and continue on Bridge over the River Kwai road to visit the Hellfire Pass Memorial. Then return to the rafts 19.00 Dinner followed by a 45–minute presentation of traditional Mon Dance and overnight at the River Kwai Jungle Rafts. Day 2 B / L / D 07.00 Breakfast. 09.00 Visit nearby ethnic Mon Tribal village & Temple and Elephant Ride River Kwai Jungle Rafts through bamboo forest. -

Trent Burnard Trent Burnard Lieutenant Colonel Commanding Officer 10Th/27Th Battalion, the Royal South Australia Regiment

Official Newsletter of the Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Editor - David Laing 0407 791 822 MARCH 2017 Inside this issue: Association BBQ Support for the Battalion Darwin - 75 Years Ago 2 About 4 weeks ago Rodney Beames received a mid week telephone call from the CO of 10/27 Bn RSAR requesting catering support for a Battalion Leadership Week- LETTERS 3 end at Keswick Barracks. “No problem!” said Beamsey, “When is it?” he asked, an- ticipating about a 10 day lead. “This weekend!” said the CO! CPL Davo’s page 4 How could Rod say anything but “How many are we feeding and what times are they dining?” How To Contact Us 5 Once that was worked out, Rod got on the phone to some members and got a reli- able, well oiled (in more ways than one) crew together, to provide sustenance for up The Radji Beach 6/7 Massacre 1942 to 30 Officers and Other Ranks attending the Leadership Exercise. The RSARA crew were present on both days to ensure the soldiers were well fed, ANZAC Day plan 8 and the fact that there was very little wastage showed how much the Diggers en- joyed the food. (See letter below.) One of our own from 9 the 10th Bn AIF Rod wishes to thank Nat Cooke, Mick Standing, Russ Durdin and Norm Rathmann, and of course Mrs Cheryl Beames who all made the support successful. Again! Members List 10 Purple & Blue Brothers 11 12 Letter of Appreciation Mr Rod Beames President Royal South Australia Regiment Association Inc Dear Rod LETTER OF APPRECIATION - SUPPORT TO 10/27 BN RSAR LEADERSHIP WEEKEND I would like to express my warmest thanks to you and your team for the support you provided to the Battalion Command Team with the provision of the lunchtime BBQ’s on our recent training weekend. -

The Road Into Burma from Thailand Into Myanmar 25

THE ROAD INTO BURMA FROM THAILAND INTO MYANMAR 25 FEBRUARY TO 19 MARCH 2017 THE ROAD INTO BURMA Modern Burma offers us a series of contradictions and makes a fascinating country to visit. We will enter the country close to the route of the ‘Burma Railway’, the name given to the railway access from Thailand constructed under the Japanese during the Second World War by prison- ners of war, with terrible loss of life. We will visit some of the war graves, as well as the bridge over the River Kwai. In Moulmein we will see the stupa celebrated in Kipling’s poem The Road to Mandalay. In Yangon, former Rangoon, and colonial capital, a number of interesting early 20th century buildings have survived which make for a good city walk. In Bagan, a landscape filled with stupas amongst the acacia trees is one of the most extraordinary sights imaginable: during the medieval period it’s been calculated that a new stupa was erected every few weeks. The tran- sition, in recent years, from military dictatorship to democracy has had us all rivetted: we have witnessed the extraordinary tenacity of Aung San Suu Kyi as she has gone from political prisoner, Nobel prize winner, to elected politician. Our journey through the country continues to the very peaceful lake at Inle. Here our hotel is raised on stilts over the lake water. We will travel to Man- dalay, whose heart is formed by a huge moated palace. In the hills above the city is the colonial summer capital at Pyin Oo Lwin, complete with clocktower, botanical gardens and half timbered houses.