A Study of Arondizuogu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources

nvironm E en l & ta i l iv E C n g Okoro et al., J Civil Environ Eng 2014, 4:1 f o i n l Journal of Civil & Environmental e a e n r r i DOI: 10.4172/2165-784X.1000134 n u g o J ISSN: 2165-784X Engineering Review Article Open Access River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources Management BC Okoro1*, RA Uzoukwu2 and NM Chimezie2 1Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria 2Department of Civil Engineering Technology, Federal Polytechnic Nekede, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria Abstract The river basins of Imo state, Nigeria are presented as a natural vital resource for sustainable water resources management in the area. The study identified most of all the known rivers in Imo State and provided information like relief, topography and other geographical features of the major rivers which are crucial to aid water management for a sustainable water infrastructure in the communities of the watershed. The rivers and lakes are classified into five watersheds (river basins) such as Okigwe watershed, Mbaise / Mbano watershed, Orlu watershed, Oguta watershed and finally, Owerri watershed. The knowledge of the river basins in Imo State will help analyze the problems involved in water resources allocation and to provide guidance for the planning and management of water resources in the state for sustainable development. Keywords: Rivers; Basins/Watersheds; Water allocation; • What minimum reservoir capacity will be sufficient to assure Sustainability adequate water for irrigation or municipal water supply, during droughts? Introduction • How much quantity of water will become available at a reservoir An understanding of the hydrology of a region or state is paramount site, and when will it become available? In other words, what in the development of such region (state). -

List of Community Banks Converted to Microfinance Banks As at 31St

CENTRAL BANK OF NIGERIA IMPORTANT NOTICE LIST OF COMMUNITY BANKS THAT HAVE SUCESSFULLY CONVERTED TO MICROFINANCE BANKS AS AT DECEMBER 31, 2007 Following the expiration of December 31, 2007 deadline for all existing community banks to re-capitalize to a minimum of N20 million shareholders’ fund, unimpaired by losses, and consequently convert to microfinance banks (MFB), it is imperative to publish the outcome of the conversion exercise for the guidance of the general public. Accordingly, the attached list represents 607 erstwhile community banks that have successfully converted to microfinance banks with either final licence or provisional approval. This list does not, however, include new investors that have been granted Final Licences or Approvals-In- Principle to operate as microfinance banks since the launch of Microfinance Policy on December 15, 2005. The Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) hereby states categorically that only the community banks on this list that have successfully converted to microfinance banks shall continue to be supervised by the CBN. Members of the public are hereby advised not to transact business with any community bank which is not on the list of these successfully converted microfinance banks. Any member of the public, who transacts business with any community bank that failed to convert to MFB does so at his/her own risk. Members of the public are also to note that the operating licences of community banks that failed to re-capitalize and consequently do not appear on this list, have automatically been revoked pursuant to Section 12 of BOFIA, 1991 (as amended). For the avoidance of the doubt, new applications either as a Unit or State Microfinance Banks from potential investors or promoters shall continue to be received and processed for licensing by the Central Bank of Nigeria. -

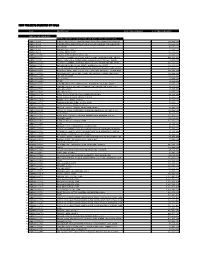

2015 Appropriation Bill

2015 APPROPRIATION ACT ZONAL INTERVENTION PROJECTS Federal Government of Nigeria APPROPRIATION ACT 2015 APPROPRIATION ACT S/N PROJECT TITLE STATE AGENCY MDA AMOUNT 1 CONSTRUCTION OF SOKOTO - JEGA - KONTAGORA ROAD SOKOTO WORKS WORKS 1,500,000,000 2 CONSTRUCTION OF MBAISE RING ROAD, IMO STATE IMO NIGER DELTA NIGER DELTA 400,000,000 3 CONSTRUCTION OF OKPALA-IGWURITA ROAD, IMO STATE IMO NIGER DELTA NIGER DELTA 100,000,000 CONSTUCTION OF CASSAVA PROCESSING FACILITY AT OKWEKENTA, NGOR OKPALA, IMO STATE 4 IMO NIGER DELTA NIGER DELTA 20,000,000 CONSTRUCTION OF CASSAVA PROCESSING FACILITY MBUTU, ABOH MBAISE, IMO STATE 5 IMO NIGER DELTA NIGER DELTA 20,000,000 6 132KVA/33 SUBSTATION AT IBEKU/AMAOHURU NGURU, IMO STATE IMO TCN POWER 90,000,000 PROCUREMENT AND INSTALLATION OF 1X15MVA/33/11KVA TRANSFORMERS AND CONSTRUCTION OF INJECTION SUBSTATION 7 AT ONICHA EZINIHITTE, IMO STATE IMO TCN POWER 60,000,000 FURNISHING OF YOUTH DEVELOPMENT CENTRE AT ABOH MBAISE, IMO STATE 8 IMO YOUTH YOUTH 20,000,000 CONSTRUCTION OF AGRICULTURE MACHINERY DEVELOPMENT INSTITUTE, MBAISE 9 IMO NASENI SCIENCE 80,000,000 LIABILITY FOR THE NODAL EXPANSION FOR NASENI PROGRAMME AT AHIARA, AHIAZU MBAISE, IMO STATE 10 IMO NASENI SCIENCE 30,000,000 LIABILITY FOR THE INSTALLATION OF SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN COMMUNITIES IN IMO STATE 11 IMO CERD, NSUKKA SCIENCE 50,000,000 PROCUREMENT AND INSTALLATION OF EQUIPMENT AT WASTE RECYCLING FACILITY AT OWERRI, IMO STATE 12 IMO ENVIRONMENT ENVIRONMENT 80,000,000 COMPLETION OF THE RECONSTRUCTIONOF CHEMISTRY AD BIOLOGY LABORATORY AT ST. PATRICK'S SECONDARY SCHOOL, OGBE AHIARA, IMO STATE 13 IMO AIRBDA WATER 8,000,000 CPMPLETION OF REHABILITATION OF FATHER WELSH ROAD EMEKUKU, OWERRI NORTH, IMO STATE 14 IMO AIRBDA WATER 30,000,000 COMPLETION OF CONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR POWERED BOREHOLE 15 AT ST. -

Godwin Valentine O= University of Nigeria, Nsukka

EZE, CAROLINE NGOZI PG/Ph.D/10/57530 MOTIVATIONAL INITIATIVES FOR CITIZENS’ PARTICIPATION IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES IN ANAMBRA AND IMO STATES OF NIGERIA FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA MURAL STUDIES Digitally Signed by: Content manager’s Name DN : CN = Webmaster’s name Godwin Valentine O= University of Nigeria, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre ii MOTIVATIONAL INITIATIVES FOR CITIZENS’ PARTICIPATION IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES IN ANAMBRA AND IMO STATES OF NIGERIA By EZE, CAROLINE NGOZI PG/Ph.D/10/57530 DEPARTMENT OF ADULT EDUCATION AND EXTRA MURAL STUDIES FACULTY OF EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA NSUKKA JULY, 2016 i TITLE PAGE MOTIVATIONAL INITIATIVES FOR CITIZENS’ PARTICIPATION IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES IN ANAMBRA AND IMO STATES OF NIGERIA By EZE, CAROLINE NGOZI PG/Ph.D/10/57530 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (Ph.D) IN ADULT EDUCATION/COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT SUPERVISOR: PROF. (MRS.) C.I. OREH JULY, 2016 ii APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved for the Department of Adult Education and Extral Mural Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. By ……………………………… …………………………… Prof. (Mrs) C.I. Oreh Thesis Supervisor Internal Examiner ……………………….. ……………………………. External Examiner Prof. S.C. Nwizu Head of Department …………………………………… Prof. Uju Umo Dean, Faculty of Education iii CERTIFICATION Eze, Caroline Ngozi a Postgraduate Student in the Department of Adult Education and Extral Mural Studies, with registration Number PG/Ph.D/10/57530, has satisfactorily completed the requirements for research work for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Adult Education/Community Development. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 22, 2017 # Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 Abatete Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abatete Town, Idemili Local Govt Area, Anambra State ANAMBRA 4 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 5 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 6 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 7 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 8 Abokie Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Plot 2, Murtala Mohammed Square, By Independence Way, Kaduna State. KADUNA 9 Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi Bauchi 10 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 11 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 12 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 13 Acheajebwa Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Sarkin Pawa Town, Muya L.G.A Niger State NIGER 14 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 15 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 16 Acuity Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 167, Adeniji Adele Road, Lagos LAGOS 17 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. -

Usein Imo State, Nigeria

Nigerian Agricultural Policy Research Journal. Volume 1, Issue 1, 2016. http://aprnetworkng.org Usein Imo State, Nigeria A. O. Ejiogu and E.C. Onyenoneke Department of Agricultural Economics, Imo State University, Owerri Corresponding author email: [email protected] Abstract child labour use in Imo State of Nigeria. Specifically, the study determined the effect of the socioeconomic factors that -stage random sampling was employed in choosing the respondents for this study. One local government area (LGA) in each of the three agricultural zones was purposively selected for the study based on suitability for rice production. Communities which are known for rice production were purposively selected from the selected LGAs. The list of rice farmers in each chosen community was obtained from Imo ADP. The list formed the sampling frame from which the respondent rice farmers were selected using random sampling procedure. Thirty rice farmers were selected from each community, making a sample size of 90.Data was analyzed with binary logistic regression technique. The variables namely gender, marital ge and educational attainment were significant at 1% level. Furthermore, gender, marital status, family size, farm size, educational attainment and rice farm experience were statistically significant variables with negatively effect on the use of child labour. Age though statistically significant, had positive effect on the use of child labour. Efforts aimed at curbing the adverse effects of child labour should to all intents and purposes be fundamentally targeted at the predisposing socioeconomic factors. Key Words: Rice farmers, labour use, socioeconomic, Imo State 1. Introduction Rice is a staple food for many people in Imo rice production in Nigeria has been identified to State, Nigeria. -

2015 Constituency Projects)

2015 FEDERAL CONSTITUENCY PROJECTS LESSONS AND FINDINGS FROM FOCUS STATES www.tracka.ng D R I V I N G S E RV I C E D E L I V E RY T H R O U G H A D V O C A C Y 16 FOCUS STATES (2015 CONSTITUENCY PROJECTS) TRACKING CONSTITUENCY PROJECTS IN SOME FOCUS STATES 17 Projects 33 Tracked 29 Projects Projects Tracked Tracked JIGAWA 33 32 KANO Projects GOMBE Projects Tracked KEBBI Tracked KADUNA 39 33 NIGER Projects Projects Tracked 31 Tracked OYO Projects Tracked KOGI OGUN ONDO A N 26 A R M E 33 Projects B V R I Projects Tracked A R S S Tracked O IMO R C DELTA 24 29 Projects Projects Tracked Tracked 29 Projects 30 Tracked Projects 18 Tracked Projects www.yourbudgit.com Tracked www.tracka.ng Tracka seeks to address a lack of access of citizens to the information of budget formulation and execution in Nigeria; it aims to empower citizens to demand transparency and accountability in the Nigerian government. The project kicked off with 16 States of the Federation, namely- Kogi, Ogun, Oyo, Kano, Edo, Delta, Anambra, Kaduna, Niger, Gombe, Lagos, Ondo, Imo, Cross River, Kebbi, and Jigawa. There are Project Tracking Officers to monitor the progress of constituency projects across the 16 focus states, exploring the use of technology to track budgets and also report feedbacks to the related executive and legislative bodies. D R I V I N G S E RV I C E D E L I V E RY T H R O U G H A D V O C A C Y INTRODUCTION Citizen-government engagement in Nigeria remains at abysmally low levels due to vestiges of past military rule, in which autocratic regimes kept the populace in obscurity about data and acts of public governance. -

2013 Federal Capital Budget Pull for South East

2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET Of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) ii 2013 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the South East Geo-Political Zone Compiled by ……………………… For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) iii First Published in September 2013 By Citizens Wealth Platform C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja Email: [email protected] iv Table of Contents Acknowledgment vi Foreword vii Abia State 1 Anambra State 16 Ebonyi State 25 Enugu State 29 Imo State 42 v Acknowledgment Citizens Wealth Platform acknowledges the financial and secretariat support of Centre for Social Justice towards the publication of this Capital Budget Pull-Out. vi Foreword This is the second year of the publication of Capital Budget Pull-outs for the six geo-political zones. Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) is setting the agenda of public participation in fiscal governance especially in monitoring and tracking capital budget implementation. Popular and targeted participation is essential to hold government accountable to the promises made in the annual budget particularly the aspects of the budget that touch on the lives of the common people. In 2013, the Federal Government of Nigeria (FGN) promised to build roads, bridges, hospitals, renovate airports and generally take actions to improve living standards. -

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: the GENDERED STRUGGLE for POWER in SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 by Leonard Ndubueze Mbah a DISSERTAT

EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2013 ABSTRACT EMERGENT MASCULINITIES: THE GENDERED STRUGGLE FOR POWER IN SOUTHEASTERN NIGERIA, 1850-1920 By Leonard Ndubueze Mbah This dissertation uses oral history, written sources, and emic interpretations of material culture and rituals to explore the impact of changes in gender constructions on the historical processes of socio-political transformation among the Ohafia-Igbo of southeastern Nigeria between 1850 and 1920. Centering Ohafia-Igbo men and women as innovative historical actors, this dissertation examines the gendered impact of Ohafia-Igbo engagements with the Atlantic and domestic slave trade, legitimate commerce, British colonialism, Scottish Christian missionary evangelism, and Western education in the 19th and 20th centuries. It argues that the struggles for social mobility, economic and political power between and among men and women shaped dynamic constructions of gender identities in this West African society, and defined changes in lineage ideologies, and the borrowing and adaptation of new political institutions. It concludes that competitive performances of masculinity and political power by Ohafia men and women underlines the dramatic shift from a pre-colonial period characterized by female bread- winners and more powerful and effective female socio-political institutions, to a colonial period of male socio-political domination in southeastern Nigeria. DEDICATION To the memory of my father, late Chief Ndubueze C. Mbah, my mother, Mrs. Janet Mbah, my teachers and Ohafia-Igbo men and women, whose forbearance made this study a reality. -

Available Online Journal of Scientific And

Available online www.jsaer.com Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 2020, 7(2):53-68 ISSN: 2394-2630 Research Article CODEN(USA): JSERBR Application of Vertical Electrical Sounding Method to Delineate Subsurface Stratification and Groundwater Occurrence in Ideato Area of Imo State, Nigeria Nwosu, L. I., Ledogo, Bright E. Department of Physics University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Twenty vertical electrical soundings (VES) were carried out in Ideato North and South areas of Imo State to delineate subsurface stratification and groundwater occurrence. Field data were acquired using Ohmega- 500 resistivity meter. The Schlumberger electrode configuration and maximum electrode spread of 900m were used. The data were interpreted using the Advanced Geosciences Incorporation (AGI) ID software and the Schlumberger automatic analysis version. Interpretative geoelectric cross-sections constructed along three profile lines delineated the subsurface stratification. The sediments consist of sequence of shale, sandstone, siltstone and clay. Around Dikenafai in Ideato-South the geology tended towards the Benin Formation. Ideato- North is more shaly than Ideato-South. Groundwater was delineated within the zone interpreted to be fractured shale with aquifer materials composed of sand, sandstone and clay sandstone and resistivity ranging from 0.10Ωm recorded at Urualla to 1035Ωm observed at Obodoukwu. Depth to water table is quite high and varied from 71.90m to 138.32m. Aquifer thickness varied across the study area with high values at Obodoukwu, Ndiadumora and Dikenafai. These areas are good prospects for groundwater development. Analysis of pumping test and VES data led to estimation of aquifer parameters for the study area. -

The Communicativeness of Incantations in the Traditional Igbo Society

Vol. 8(7),pp. 63-70, October 2016 DOI: 10.5897/JMCS2016.0512 Article Number: 3ABBDF561047 ISSN: 2141-2545 Journal of Media and Communication Studies Copyright ©2016 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournlas.org/JMCS Full Length Research Paper The communicativeness of incantations in the traditional Igbo society Walter Duru Department of Communication Arts, University of Uyo, Uyo, Nigeria. Received 06 June, 2016; Accepted 19 September, 2016 This paper examines the communicativeness of incantations in the traditional Igbo society. Incantations are given force by oral tradition, a practice whereby the social, political, economic and cultural heritage of the people is communicated by word of mouth from one generation to another. It was the most predominant part of communication in many parts of Africa. Prior to colonialism, the African society, including the Igbo used oral tradition as a veritable tool in information gathering, sharing/dissemination and indeed worship. They lived normal and satisfactory lives, cultivated, built, ate, sang, danced, healed their sick, created and communicated. Incantation is one of the modes of communication in the traditional Igbo society. In an incantation, all words stand for something and are meaningful. Most of the cultural displays of the Igbo society employ incantations in communicating with spirits. While some aspects of the practice may appear fetish and obsolete, several others are purely traditional and, destroying it out-rightly amounts to throwing away a baby with the dirty water. This article traces the effectiveness of incantation as a mode of communication, examines its uses and purposes, while highlighting the implications of allowing it go into extinction.