Mizraḥ U-Ma'arav (East and West)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Privatizing Religion: the Transformation of Israel's

Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious- Zionist community BY Yair ETTINGER The Brookings Institution is a nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. This paper is part of a series on Imagining Israel’s Future, made possible by support from the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund. The views expressed in this report are those of its author and do not represent the views of the Morningstar Philanthropic Fund, their officers, or employees. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, NW Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu Table of Contents 1 The Author 2 Acknowlegements 3 Introduction 4 The Religious Zionist tribe 5 Bennett, the Jewish Home, and religious privatization 7 New disputes 10 Implications 12 Conclusion: The Bennett era 14 The Center for Middle East Policy 1 | Privatizing religion: The transformation of Israel’s Religious-Zionist community The Author air Ettinger has served as a journalist with Haaretz since 1997. His work primarily fo- cuses on the internal dynamics and process- Yes within Haredi communities. Previously, he cov- ered issues relating to Palestinian citizens of Israel and was a foreign affairs correspondent in Paris. Et- tinger studied Middle Eastern affairs at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and is currently writing a book on Jewish Modern Orthodoxy. -

Aliyah and Settlement Process?

Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel HBI SERIES ON JEWISH WOMEN Shulamit Reinharz, General Editor Joyce Antler, Associate Editor Sylvia Barack Fishman, Associate Editor The HBI Series on Jewish Women, created by the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute, pub- lishes a wide range of books by and about Jewish women in diverse contexts and time periods. Of interest to scholars and the educated public, the HBI Series on Jewish Women fills major gaps in Jewish Studies and in Women and Gender Studies as well as their intersection. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com and www.upne.com/series/BSJW.html. Ruth Kark, Margalit Shilo, and Galit Hasan-Rokem, editors, Jewish Women in Pre-State Israel: Life History, Politics, and Culture Tova Hartman, Feminism Encounters Traditional Judaism: Resistance and Accommodation Anne Lapidus Lerner, Eternally Eve: Images of Eve in the Hebrew Bible, Midrash, and Modern Jewish Poetry Margalit Shilo, Princess or Prisoner? Jewish Women in Jerusalem, 1840–1914 Marcia Falk, translator, The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible Sylvia Barack Fishman, Double or Nothing? Jewish Families and Mixed Marriage Avraham Grossman, Pious and Rebellious: Jewish Women in Medieval Europe Iris Parush, Reading Jewish Women: Marginality and Modernization in Nineteenth-Century Eastern European Jewish Society Shulamit Reinharz and Mark A. Raider, editors, American Jewish Women and the Zionist Enterprise Tamar Ross, Expanding the Palace of Torah: Orthodoxy and Feminism Farideh Goldin, Wedding Song: Memoirs of an Iranian Jewish Woman Elizabeth Wyner Mark, editor, The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite Rochelle L. -

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940

Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Open Jerusalem Edited by Vincent Lemire (Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée University) and Angelos Dalachanis (French School at Athens) VOLUME 1 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/opje Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access Ordinary Jerusalem 1840–1940 Opening New Archives, Revisiting a Global City Edited by Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire LEIDEN | BOSTON Angelos Dalachanis and Vincent Lemire - 978-90-04-37574-1 Downloaded from Brill.com03/21/2019 10:36:34AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing CC-BY-NC-ND License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. The Open Jerusalem project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) (starting grant No 337895) Note for the cover image: Photograph of two women making Palestinian point lace seated outdoors on a balcony, with the Old City of Jerusalem in the background. American Colony School of Handicrafts, Jerusalem, Palestine, ca. 1930. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/item/mamcol.054/ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Dalachanis, Angelos, editor. -

Special Lecture by Dr. Marc Shapiro,New

The Nazir in New York ב”ה The Nazir in New York Josh Rosenfeld I. Mishnat ha-Nazir הוצאת נזר דוד שע”י מכון אריאל ירושלים, 2005 קכ’36+ עמודים הראל כהן וידידיה כהן, עורכים A few years ago, during his daily shiur, R. Herschel Schachter related that he and his wife had met someone called ‘the Nazir’ during a trip to Israel. R. Schachter quoted the Nazir’s regarding the difficulty Moshe had with the division of the land in the matter the daughters of Zelophehad and the Talmudic assertion (Baba Batra 158b) that “the air of the Land of Israel enlightens”. Although the gist of the connection I have by now unfortunately forgotten, what I do remember is R. Schachter citing the hiddush of a modern-day Nazir, and how much of a curio it was at the time. ‘The Nazir’, or R. David Cohen (1887-1972) probably would have been quite satisfied with that. Towards the end of Mishnat ha-Nazir (Jerusalem, 2005) – to my knowledge, the most extensive excerpting of the Nazir’s diaries since the the three-volume gedenkschrift Nezir Ehav (Jerusalem, 1978), and the selections printed in Prof. Dov Schwartz’ “Religious Zionism: Between Messianism and Rationalism” (Tel Aviv, 1999) – we see the Nazir himself fully conscious of the hiddush :(עמ’ ע) of his personal status נזיר הנני, שם זה הנני נושא בהדר קודש. אלמלא לא באתי אלא בשביל זה, לפרסם שם זה, להיות בלבות זרע קודש ישראל, צעירי הצאן, זכרונות קודשי עברם הגדול, בגילוי שכינה, טהרה וקדושה, להכות בלבם הרך גלי געגועים לעבר זה שיקום ויהיה לעתיד, חידוש ימינו כקדם, גם בשביל זה כדאי לשאת ולסבול and :(זכרונות מבית אבא מארי ,similarly (p. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents From the Editors 3 From the President 3 From the Executive Director 5 The Sound Issue “Overtures” Music, the “Jew” of Jewish Studies: Updated Readers’ Digest 6 Edwin Seroussi To Hear the World through Jewish Ears 9 Judah M. Cohen “The Sound of Music” The Birth and Demise of Vocal Communities 12 Ruth HaCohen Brass Bands, Jewish Youth, and the Sonorities of a Global Perspective 14 Maureen Jackson How to Get out of Here: Sounding Silence in the Jewish Cabaretesque 20 Philip V. Bohlman Listening Contrapuntally; or What Happened When I Went Bach to the Archives 22 Amy Lynn Wlodarski The Trouble with Jewish Musical Genres: The Orquesta Kef in the Americas 26 Lillian M. Wohl Singing a New Song 28 Joshua Jacobson “Sounds of a Nation” When Josef (Tal) Laughed; Notes on Musical (Mis)representations 34 Assaf Shelleg From “Ha-tikvah” to KISS; or, The Sounds of a Jewish Nation 36 Miryam Segal An Issue in Hebrew Poetic Rhythm: A Cognitive-Structuralist Approach 38 Reuven Tsur Words, Melodies, Hands, and Feet: Musical Sounds of a Kerala Jewish Women’s Dance 42 Barbara C. Johnson Sound and Imagined Border Transgressions in Israel-Palestine 44 Michael Figueroa The Siren’s Song: Sound, Conflict, and the Politics of Public Space in Tel Aviv 46 Abigail Wood “Surround Sound” Sensory History, Deep Listening, and Field Recording 50 Kim Haines-Eitzen Remembering Sound 52 Alanna E. Cooper Some Things I Heard at the Yeshiva 54 Jonathan Boyarin The Questionnaire What are ways that you find most useful to incorporate sound, images, or other nontextual media into your Jewish Studies classrooms? 56 Read AJS Perspectives Online at perspectives.ajsnet.org AJS Perspectives: The Magazine of President Please direct correspondence to: the Association for Jewish Studies Pamela Nadell Association for Jewish Studies From the Editors perspectives.ajsnet.org American University Center for Jewish History 15 West 16th Street Dear Colleagues, Vice President / Program New York, NY 10011 Editors Sounds surround us. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

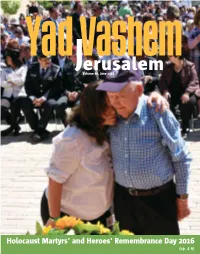

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

JEWISH HISTORY in CONFLICT

JEWISH HISTORY in CONFLICT JEWISH HISTORY in CONFLICT MITCHELL FIRST JASON ARONSON INC. Northvale, New Jersey Jerusalem This book was set in 11 pt. Weiss by Alabama Book Compos~tionof Deatsville, Alabama, and printed and bound by Book-mart Press of North Bergen, New Jersey. Copyright O 1997 by Mitchell First All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from Jason Aronson Inc, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data First, Mitchell, 1958- Jewish history in conflict : a study of the discrepancy between rabbinic and conventional chronology 1 ~MitchellFirst. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978- 1-5682 1-970-7 1. Seder olam rabbah. 2. Jews-History-586 B.C.-70 A.D.- Chronology. 3. Jews-History-586 B.C.-70 A.D.-Historiography. 4. Jewish historians-Attitudes. I. Title. DS 1 14.F57 1997 909'.04924-dc20 96-28086 Manufactured in the United States of America. Jason Aronson Inc. offers books and cassettes For information and catalog write to Jason Aronson Inc., 230 Livingston Street, Northvale, New Jersey 07647. To my wife, Sharon and To our children, Shaya, Daniel, and Rachel and To my parents Con tents Acknowledgments xiii Abbreviations xv Diagram xvii Statement of Purpose xix PARTI: INTRODUCTION TO THE DISCREPANCY The SO Chronology The Conventional Chronology The Discrepancy PART11: THEEARLIEST JEWISH RESPONSESTO THE DISCREPANCY 1 Saadiah Gaon 11 2 Seder Malkhei Romi 13 3 Josippon 14 4 Isaac Abravanel 17 5 Abraham Zacuto 19 Category A-SO Chronology Is Correct: Conventional Chronology Is in Error 2 6 i David Canz 27 2 Judah Loew 2 9 , , . -

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D

Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs by Daniel D. Stuhlman BHL, BA, MS LS, MHL In support of the Doctor of Hebrew Literature degree Jewish University of America Skokie, IL 2004 Page 1 Abstract Hebrew Names and Name Authority in Library Catalogs By Daniel D. Stuhlman, BA, BHL, MS LS, MHL Because of the differences in alphabets, entering Hebrew names and words in English works has always been a challenge. The Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) is the source for many names both in American, Jewish and European society. This work examines given names, starting with theophoric names in the Bible, then continues with other names from the Bible and contemporary sources. The list of theophoric names is comprehensive. The other names are chosen from library catalogs and the personal records of the author. Hebrew names present challenges because of the variety of pronunciations. The same name is transliterated differently for a writer in Yiddish and Hebrew, but Yiddish names are not covered in this document. Family names are included only as they relate to the study of given names. One chapter deals with why Jacob and Joseph start with “J.” Transliteration tables from many sources are included for comparison purposes. Because parents may give any name they desire, there can be no absolute rules for using Hebrew names in English (or Latin character) library catalogs. When the cataloger can not find the Latin letter version of a name that the author prefers, the cataloger uses the rules for systematic Romanization. Through the use of rules and the understanding of the history of orthography, a library research can find the materials needed. -

Reform Or Consensus? Choral Synagogues in the Russian Empire

arts Article Reform or Consensus? Choral Synagogues in the Russian Empire Vladimir Levin The Center for Jewish Art, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 9190501, Israel; [email protected] Received: 5 May 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020; Published: 23 June 2020 Abstract: Many scholars view the choral synagogues in the Russian Empire as Reform synagogues, influenced by the German Reform movement. This article analyzes the features characteristic of Reform synagogues in central and Western Europe, and demonstrates that only a small number of these features were implemented in the choral synagogues of Russia. The article describes the history, architecture, and reception of choral synagogues in different geographical areas of the Russian Empire, from the first maskilic synagogues of the 1820s–1840s to the revolution of 1917. The majority of changes, this article argues, introduced in choral synagogues were of an aesthetic nature. The changes concerned decorum, not the religious meaning or essence of the prayer service. The initial wave of choral synagogues were established by maskilim, and modernized Jews became a catalyst for the adoption of the choral rite by other groups. Eventually, the choral synagogue became the “sectorial” synagogue of the modernized elite. It did not have special religious significance, but it did offer social prestige and architectural prominence. Keywords: synagogue; Jewish history in Russia; reform movement; Haskalah; synagogue architecture; Jewish cultural studies; Jewish architecture 1. Introduction The synagogue was the most important Jewish public space until the emergence of secular institutions in the late nineteenth century. As such, it was a powerful means of representation of the Jewish community in its own eyes and in the eyes of the non-Jewish population. -

The Sephardim of the United States: an Exploratory Study

The Sephardim of the United States: An Exploratory Study by MARC D. ANGEL WESTERN AND LEVANTINE SEPHARDIM • EARLY AMERICAN SETTLEMENT • DEVELOPMENT OF AMERICAN COMMUNITY • IMMIGRATION FROM LEVANT • JUDEO-SPANISH COMMUNITY • JUDEO-GREEK COMMUNITY • JUDEO-ARABIC COMMUNITY • SURVEY OF AMERICAN SEPHARDIM • BIRTHRATE • ECO- NOMIC STATUS • SECULAR AND RELIGIOUS EDUCATION • HISPANIC CHARACTER • SEPHARDI-ASHKENAZI INTERMARRIAGE • COMPARISON OF FOUR COMMUNITIES INTRODUCTION IN ITS MOST LITERAL SENSE the term Sephardi refers to Jews of Iberian origin. Sepharad is the Hebrew word for Spain. However, the term has generally come to include almost any Jew who is not Ashkenazi, who does not have a German- or Yiddish-language background.1 Although there are wide cultural divergences within the Note: It was necessary to consult many unpublished sources for this pioneering study. I am especially grateful to the Trustees of Congregation Shearith Israel, the Spanish and Portuguese Synagogue in New York City, for permitting me to use minutes of meetings, letters, and other unpublished materials. I am also indebted to the Synagogue's Sisterhood for making available its minutes. I wish to express my profound appreciation to Professor Nathan Goldberg of Yeshiva University for his guidance throughout every phase of this study. My special thanks go also to Messrs. Edgar J. Nathan 3rd, Joseph Papo, and Victor Tarry for reading the historical part of this essay and offering valuable suggestions and corrections, and to my wife for her excellent cooperation and assistance. Cecil Roth, "On Sephardi Jewry," Kol Sepharad, September-October 1966, pp. 2-6; Solomon Sassoon, "The Spiritual Heritage of the Sephardim," in Richard Barnett, ed., The Sephardi Heritage (New York, 1971), pp. -

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’Vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn

צב | עב January Tevet | Sh’vat Capricorn Saturn | Aquarius Saturn Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 | 17th of Tevet* 2 | 18th of Tevet* New Year’s Day Parashat Vayechi Abraham Moshe Hillel Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech of Dinov Rabbi Salman Mutzfi Rabbi Huna bar Mar Zutra & Rabbi Rabbi Yaakov Krantz Mesharshya bar Pakod Rabbi Moshe Kalfon Ha-Cohen of Jerba 3 | 19th of Tevet * 4* | 20th of Tevet 5 | 21st of Tevet * 6 | 22nd of Tevet* 7 | 23rd of Tevet* 8 | 24th of Tevet* 9 | 25th of Tevet* Parashat Shemot Rabbi Menchachem Mendel Yosef Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon Rabbi Leib Mochiach of Polnoi Rabbi Hillel ben Naphtali Zevi Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi Rabbi Yaakov Abuchatzeira Rabbi Yisrael Dov of Vilednik Rabbi Schulem Moshkovitz Rabbi Naphtali Cohen Miriam Mizrachi Rabbi Shmuel Bornsztain Rabbi Eliyahu Eliezer Dessler 10 | 26th of Tevet* 11 | 27th of Tevet* 12 | 28th of Tevet* 13* | 29th of Tevet 14* | 1st of Sh’vat 15* | 2nd of Sh’vat 16 | 3rd of Sh’vat* Rosh Chodesh Sh’vat Parashat Vaera Rabbeinu Avraham bar Dovid mi Rabbi Shimshon Raphael Hirsch HaRav Yitzhak Kaduri Rabbi Meshulam Zusha of Anipoli Posquires Rabbi Yehoshua Yehuda Leib Diskin Rabbi Menahem Mendel ben Rabbi Shlomo Leib Brevda Rabbi Eliyahu Moshe Panigel Abraham Krochmal Rabbi Aryeh Leib Malin 17* | 4th of Sh’vat 18 | 5th of Sh’vat* 19 | 6th of Sh’vat* 20 | 7th of Sh’vat* 21 | 8th of Sh’vat* 22 | 9th of Sh’vat* 23* | 10th of Sh’vat* Parashat Bo Rabbi Yisrael Abuchatzeirah Rabbi Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter Rabbi Chaim Tzvi Teitelbaum Rabbi Nathan David Rabinowitz