Report from a Cuban Prison VII: New Year's Eve Celebration and a Little

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba Travelogue 2012

Havana, Cuba Dr. John Linantud Malecón Mirror University of Houston Downtown Republic of Cuba Political Travelogue 17-27 June 2012 The Social Science Lectures Dr. Claude Rubinson Updated 12 September 2012 UHD Faculty Development Grant Translations by Dr. Jose Alvarez, UHD Ports of Havana Port of Mariel and Matanzas Population 313 million Ethnic Cuban 1.6 million (US Statistical Abstract 2012) Miami - Havana 1 Hour Population 11 million Negative 5% annual immigration rate 1960- 2005 (Human Development Report 2009) What Normal Cuba-US Relations Would Look Like Varadero, Cuba Fisherman Being Cuban is like always being up to your neck in water -Reverend Raul Suarez, Martin Luther King Center and Member of Parliament, Marianao, Havana, Cuba 18 June 2012 Soplillar, Cuba (north of Hotel Playa Giron) Community Hall Questions So Far? José Martí (1853-95) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Che Guevara (1928-67) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Derek Chandler International Airport Exit Doctor Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-59) Havana-Plaza De La Revolución + Assorted Locations Havana Museo de la Revolución Batista Reagan Bush I Bush II JFK? Havana Museo de la Revolución + Assorted Locations The Cuban Five Havana Avenue 31 North-Eastbound M26=Moncada Barracks Attack 26 July 1953/CDR=Committees for Defense of the Revolution Armed Forces per 1,000 People Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12 Questions So Far? pt. 2 Marianao, Havana, Grade School Fidel Raul Che Fidel Che Che 2+4=6 Jerry Marianao, Havana Neighborhood Health Clinic Fidel Raul Fidel Waiting Room Administrative Area Chandler Over Entrance Front Entrance Marianao, Havana, Ration Store Food Ration Book Life Expectancy Source: World Bank (http://databank.worldbank.org/data/Home.aspx) 24 May 12. -

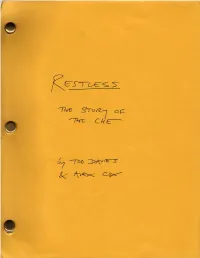

Restless.Pdf

RESTLESS THE STORY OF EL ‘CHE’ GUEVARA by ALEX COX & TOD DAVIES first draft 19 jan 1993 © Davies & Cox 1993 2 VALLEGRANDE PROVINCE, BOLIVIA EXT EARLY MORNING 30 JULY 1967 In a deep canyon beside a fast-flowing river, about TWENTY MEN are camped. Bearded, skinny, strained. Most are asleep in attitudes of exhaustion. One, awake, stares in despair at the state of his boots. Pack animals are tethered nearby. MORO, Cuban, thickly bearded, clad in the ubiquitous fatigues, prepares coffee over a smoking fire. "CHE" GUEVARA, Revolutionary Commandant and leader of this expedition, hunches wheezing over his journal - a cherry- coloured, plastic-covered agenda. Unable to sleep, CHE waits for the coffee to relieve his ASTHMA. CHE is bearded, 39 years old. A LIGHT flickers on the far side of the ravine. MORO Shit. A light -- ANGLE ON RAUL A Bolivian, picking up his M-1 rifle. RAUL Who goes there? VOICE Trinidad Detachment -- GUNFIRE BREAKS OUT. RAUL is firing across the river at the light. Incoming bullets whine through the camp. EVERYONE is awake and in a panic. ANGLE ON POMBO CHE's deputy, a tall Black Cuban, helping the weakened CHE aboard a horse. CHE's asthma worsens as the bullets fly. CHE Chino! The supplies! 3 ANGLE ON CHINO Chinese-Peruvian, round-faced and bespectacled, rounding up the frightened mounts. OTHER MEN load the horses with supplies - lashing them insecurely in their haste. It's getting light. SOLDIERS of the Bolivian Army can be seen across the ravine, firing through the trees. POMBO leads CHE's horse away from the gunfire. -

Huber Matos Incansable Defensor De La Libertad En Cuba

Personajes Públicos Nº 003 Marzo de 2014 Huber Matos Incansable defensor de la libertad en Cuba. Este 27 de febrero murió en Miami, de un ataque al corazón, a los 95 años. , Huber Matos nació en 1928 en Yara, Cuba. guerra le valió entrar con Castro y Cienfue- El golpe de Estado de Fulgencio Batista (10 gos en La Habana, en la marcha de los vence- de marzo de 1952) lo sorprendió a sus veinti- dores (como se muestra en la imagen). cinco años, ejerciendo el papel de profesor en una escuela de Manzanillo. Años antes había conseguido un doctorado en Pedagogía por la Universidad de La Habana, lo cual no impidió, sin embargo, que se acoplara como paramili- tar a la lucha revolucionaria de Fidel Castro. Simpatizante activo del Partido Ortodoxo (de ideas nacionalistas y marxistas), se unió al Movimiento 26 de Julio (nacionalista y antiimperialista) para hacer frente a la dicta- dura de Fulgencio Batista, tras enterarse de la muerte de algunos de sus pupilos en la batalla De izquierda a derecha y en primer plano: de Alegría de Pío. El movimiento le pareció Camilo Cienfuegos, Fidel Castro y Huber Matos. atractivo, además, porque prometía volver a la legalidad y la democracia, y respetar la Una vez conquistado el país, recibió la Constitución de 1940. Arrestado por su comandancia del Ejército en Camagüey, pero oposición a Batista, escapó exitosamente a adoptó una posición discrepante de Fidel, a Costa Rica, país que perduró sentimental- quien atribuyó un planteamiento comunista, mente en su memoria por la acogida que le compartido por el Ché Guevara y Raúl dio como exiliado político. -

RESEÑAS 326 Reseñas

RESEÑAS 326 Reseñas Alarcón Ramírez, Dariel (“Benigno”). Memorias de un soldado cubano: Vida y muerte de la Revolución. Barcelona: Lumen&Tusquets Editores, 1a. edición en español, 1997, Colección Andanzas; 3a. edición en español, 2004, Colección Fábula. 360 páginas. Título original en francés: Vie et mort de la révolution cubaine. Fernando Cubides Profesor Titular, Departamento de Sociología Universidad Nacional de Colombia, sede Bogotá Sobreviviente. Así de escueta es la definición final que la editora de estas memorias ofrece del personaje que las relata. Parece evocar la manera en que se definía uno de los protagonistas claves de la Revolución Francesa para resumir los méritos de su propia participación: el Abate Sieyès, cuando la misma había terminado su ciclo histórico: “Sobreviví” ( “J’ai véçu”). Y es que, por lo visto, tratándose de revoluciones, haber participado en una de ellas, y haberla sobrevivi- do, es ya un mérito formidable. “Benigno”, el nombre de guerra con el que figura en el diario del Ché en Bolivia; o Dariel Alarcón Ramírez, como figura en el pasaporte francés como asilado político; o Dariel Roselló Ramírez, como debería haberse llamado este hijo de militar español y criolla cubana, si las circunstancias no lo hubiesen separado de sus padres en la primera infancia; es pues, ante todo un sobreviviente. Condición que impresiona más si se tiene en cuenta que al triunfo de la Revolución no inicia un ascenso en cargos de responsabilidad política, pues su analfabetismo sumado a una ingenuidad campesina –guajira– se lo impiden, sino que es asignado a las misiones más difíciles para las que ya fuere Camilo Cienfuegos, o el Ché Guevara, o el propio Fidel, lo consideran especialmente dotado dada sus cualidades de hombre de guerra, probadas desde las primeras acciones en las que toma parte. -

Sweig, Julia. Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground

ACHSC / 32 / Romero Sweig, Julia. Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. Cambridge (Massachusetts): Harvard University Press, 2002. 254 páginas. Susana Romero Sánchez Estudiante, Maestría en Historia Universidad Nacional de Colombia Inside the Cuban Revolution es uno de los últimos trabajos sobre la revolución cubana, incluso se ha dicho que es el definitivo, escrito por la investigadora en relaciones internacionales con América Latina y Cuba, Julia Sweig, del Consejo para las Relaciones Internacionales de Estados Unidos y de la Universidad John Hopkins. El libro trata a la revolución cubana desde dentro (como su título lo insinúa), es decir, narra la historia del Movimiento 26 de julio (M267) –sus conflictos y sus disputas internas; mientras, paralelamente, explica cómo ese movimiento logró liderar la oposición a Fulgencio Batista y cómo se produjo el proceso revolucionario, en un período que comprende desde los primeros meses de 1957 hasta la formación del primer gabinete del gobierno revolucionario, durante los primeros días de enero de 1959. En lo que respecta a la historia del 26 de julio, la autora se preocupa principalmente de la relación entre las fuerzas del llano y de la sierra, y sobre el proceso revolucionario, el libro profundiza en cómo el M267 se convirtió en la fuerza más popular de la oposición y en su relación con las demás organizaciones. Uno de los grandes aportes de Sweig es que logra poner en evidencia fuentes documentales cubanas, a las cuales ningún investigador había podido tener acceso con anterioridad. Esas nuevas fuentes consisten en el fondo documental Celia Sánchez, de la Oficina de Asuntos Históricos de La Habana, el cual contiene correspondencia entre los dirigentes –civiles y militares–1 del Movimiento 26 de julio, informes y planes operacionales durante la “lucha contra la tiranía”, es decir, desde que Fulgencio Batista dio el golpe de estado a Carlos Prío Socarrás, el 10 de marzo de 1952, hasta el triunfo de la revolución cubana, en enero de 1959. -

A Missing Story in Havana: a Conversation with Juan Moreira July 8, 2016 Juan Moreira Studio, Havana, Cuba

Zheng Shengtian A Missing Story in Havana: A Conversation with Juan Moreira July 8, 2016 Juan Moreira Studio, Havana, Cuba This interview is an extension of my research into exchanges between Latin Left to right: Zheng Shengtian, Marisol Villela, Juan Moreira. America and China during the 1950s and 60s—in particular with Chilean Photo: Don Li-Leger. artist José Venturelli and his influence in mainland China. In the 1960s, Cuban artist Juan Moreira assisted Venturelli in the painting of two large murals in Havana.1 Zheng Shengtian: May I call you Juan? We are of the same generation. 44 Vol. 16 No. 1 Juan Moreira: Yes, of course. Zheng Shengtian: Juan, when I was a young artist in the early 1960s, I was in China, in Beijing, and we learned about the painting Camilo Cienfuegos (1961). Juan Moreira: It is José Venturelli’s mural. Zheng Shengtian: Venturelli lived in Beijing at that time, and he came to Havana and made two murals—Camilo Cienfuegos, in the Medical Retreat (now the Ministry of Health), and another, Sovereignty and Peace, in the Hall of Solidarity at Habana Libre, the former Havana Hilton hotel that was once the headquarters of Fidel Castro. In 1962 Venturelli went back to Beijing and showed his drawings of the mural Camilo Cienfuegos as well as photographs of it. So many artists in China, in Beijing, were very impressed by this mural. In more than half a century, however, no one in China actually has seen the painting, no one has seen the original. But we saw it today, with Chinese artists Zhang Peili and Geng Jianyi who are visiting Havana with me. -

Ags Cover-R1

TASK FORCE REPORT U.S.-Cuban Relations in the 21st Century U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS IN THE 21 A FOLLOW-ON CHAIRMAN’S REPORT OF AN INDEPENDENT TASK FORCE SPONSORED BY THE COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS U.S.-CUBAN In a significant departure from legislation passed by Congress and signed into law by the president in October 2000, a high-level Task Force of conservatives and lib- erals recommends the United States move quickly to clear away the policy under- ST brush and prepare for the next stage in U.S.-Cuban relations. This report, a follow- CENTURY up to the 1999 report also sponsored by the Council on Foreign Relations, sets forth a number of useful steps—short of lifting general economic sanctions and establish- ing diplomatic relations—that it says can and should be taken to prepare for the tran- RELATIONS IN THE sition in bilateral relations and on the island. Headed by former Assistant Secretaries of State for Inter-American Affairs Bernard W. Aronson and William D. Rogers, this report calls for new initiatives beyond recent congressional action. For example: it urges the sale of agricultural and ST medical products with commercial U.S. financing and allowing travel to Cuba by all Americans. The report also recommends: 21 CENTURY: • limited American investment to support the Cuban private sector and increased American travel to Cuba; • resolving expropriation claims by licensing American claimants to negotiate set- tlements directly with Cuba, including equity participation; A FOLLOW-ON • actively promoting international labor standards in Cuba; • supporting Cuban observer status in the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and Inter-American Development Bank; • direct commercial flights and ferry services; REPORT • increasing counternarcotics cooperation; • developing exchanges between the U.S. -

Los Días Del Triunfo

Los días del triunfo Cuando el Palacio pasó a ser nada atista tomó las de Villadiego cuando la candela lo sacó de su concha de caracol, dejando en una situación embarazosa a B quienes confiaron en él hasta el último momento. Abandonó el Palacio Presidencial pasadas las 2:00 de la tarde del miércoles 31 de diciembre de 1959 para dirigirse a su finca Kuquine y ya jamás volvería a poner un pie en el despacho del se- gundo piso, donde tan jugosos frutos había cosechado de la Silla de doña Pilar. O de la otra que la había sustituido por órdenes expresas suyas. Su mujer e hijos habían salido con rumbo a la Casa Militar del Presidente en Columbia, donde se les unió Batista cuando iban a dar las 12:00 de la noche. Y de allí a la fuga. De modo que al menos durante cinco días el Palacio resultó un edificio tan inútil en su función ejecutiva como pudo serlo cual- quier otro de los alrededores. Era la primera vez que se producía una circunstancia de esa naturaleza desde el 31 de enero de 1920, cuando fue inaugurado con bombos y platillos por Mario García Menocal. Hubo, sí, un intento por ocupar el sillón vacío el 1ro de enero de 1959; pero la cosa no pasó de ahí. Los ideólogos de aquel plan fueron el propio Batista y el general Eulogio Cantillo, quien enca- bezó una junta militar y ordenó ir en busca del magistrado de más antigüedad en la Audiencia, a quien correspondía asumir el cargo por imposibilidad del vicepresidente y el secretario de Estado, ambos dados a la fuga junto a Fulgencio Batista. -

Review of Julia E. Sweig's Inside the Cuban Revolution

Inside the Cuban Revolution: Fidel Castro and the Urban Underground. By Julia E. Sweig. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2002. xx, 255 pp. List of illustrations, acknowledgments, abbre- viations, about the research, notes, bibliography, index. $29.95 cloth.) Cuban studies, like former Soviet studies, is a bipolar field. This is partly because the Castro regime is a zealous guardian of its revolutionary image as it plays into current politics. As a result, the Cuban government carefully screens the writings and political ide- ology of all scholars allowed access to official documents. Julia Sweig arrived in Havana in 1995 with the right credentials. Her book preface expresses gratitude to various Cuban government officials and friends comprising a who's who of activists against the U.S. embargo on Cuba during the last three decades. This work, a revision of the author's Ph.D. dissertation, ana- lyzes the struggle of Fidel Castro's 26th of July Movement (M-26-7) against the Fulgencio Batista dictatorship from November 1956 to July 1958. Sweig recounts how the M-26-7 urban underground, which provided the recruits, weapons, and funds for the guerrillas in the mountains, initially had a leading role in decision making, until Castro imposed absolute control over the movement. The "heart and soul" of this book is based on nearly one thousand his- toric documents from the Cuban Council of State Archives, previ- ously unavailable to scholars. Yet, the author admits that there is "still-classified" material that she was unable to examine, despite her repeated requests, especially the correspondence between Fidel Castro and former president Carlos Prio, and the Celia Sánchez collection. -

Reseña De" Cómo Llegó La Noche. Revolución Y Condena De Un

Revista Mexicana del Caribe ISSN: 1405-2962 [email protected] Universidad de Quintana Roo México Camacho Navarro, Enrique Reseña de "Cómo llegó la noche. Revolución y condena de un idealista cubano. Memorias" de Huber Matos Revista Mexicana del Caribe, vol. VII, núm. 14, 2002, pp. 217-224 Universidad de Quintana Roo Chetumal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=12871407 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto RESEÑAS Huber Matos, Cómo llegó la noche. Revolución y condena de un idealista cubano. Memorias, prólogos de Hugh Thomas y Carlos Echeverría, Barce- lona, Tusquets (Tiempo de Memoria, 19), 2002. n marzo de 2003 tuve en mis manos un libro que se había E editado un año atrás. Se trataba del material que en el 2001 fue galardonado por el jurado del Premio Comillas de biografía, autobiografía y memorias. Jorge Semprún, en calidad de presi- dente, además de Miguel Ángel Aguilar, Ma. Teresa Castells, Jorge Edwards, Santos Juliá y Antonio López Lamadrid en representa- ción de Tusquets Editores, fueron los integrantes de dicho jurado. Desde su publicación se desarrolló una fuerte promoción en torno a ese texto y a su autor. En México se realizaron varias presen- taciones del autor e innumerables reseñas. Pese a que mi contacto con la obra fue tardío —es decir, sin estar al ritmo urgente de las modas académicas—, llevé a cabo mi lectura de Cómo llegó la noche. -

Stifling Dissent in the Midst of Crisis

February, 1994 Volume VI, Number 2 CUBA STIFLING DISSENT IN THE MIDST OF CRISIS INDEX FOREWORD..................................................................................................................2 I. THE STATE OF HUMAN RIGHTS IN CUBA TODAY................................... 3 II. DANGEROUSNESS .............................................................................................. 4 III. DESPITE LOOSENED TRAVEL, RESTRICTIONS REMAIN....................... 5 IV. POLITICAL PRISONERS RELEASED.............................................................. 6 V. HUMAN RIGHTS MONITORING, ADVOCACY PROHIBITED................ 7 a. Cuban Committee for Human Rights ........................................................... 8 b. Cuban Commission for Human Rights and National Reconciliation......8 c. José Martí National Commission on Human Rights ...................................9 d. Association of Defenders of Political Rights.................................................9 e. Indio Feria Democratic Union .........................................................................9 f. Cuban Humanitarian Women's Movement ..................................................9 g. International Human Rights Monitoring Curtailed..................................10 VI. ARRESTS AND IMPRISONMENT OF DEMOCRACY ACTIVISTS........ 10 a. Harmony Movement.......................................................................................10 b. Liberación..........................................................................................................10 -

Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies Hispanic Studies 2012 Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity Krissie Butler University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Butler, Krissie, "Deconstructing an Icon: Fidel Castro and Revolutionary Masculinity" (2012). Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies. 10. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/hisp_etds/10 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Hispanic Studies at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Hispanic Studies by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained and attached hereto needed written permission statements(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine). I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the non-exclusive license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless a preapproved embargo applies. I retain all other ownership rights to the copyright of my work.