Culture, Healing Practice Pluralism and Living with Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

For My Short Witty Poems and for My Humorous Poems

Dear (I hope) Reader, A note from the poet: I'm probably best known (or unknown) for my short witty poems and for my humorous poems. None of the following poems are short, and most are not particularly witty or humorous, nor are they particularly rich in lyricism, image or "telling details" -- in fact, they are rather abstract, and have on occasion been praised or dismissed as "not poetry, but philosophical essays or sermons"; they are difficult, chunky with unpoeticized thought processes, perhaps arrogant and pontifical and preachy. Perhaps most are unpublishable (except here) -- though a few of them have been published. But they are the poems (of my own, that is) that please me most and seem to me, for all their faults, to do best what I want to do as a poet, something I have always felt needed doing and that few others seemed to be doing. These are the poems for which I'd most like to be remembered and the poems I feel others might find most valuable, though requiring a bit more work than my other poems. I won't try to explain what it is I want these poems to do, but hope that you'll read some of them and come to your own conclusions. Let me know what you think. Best, Dean Blehert [email protected] Lest We Forget Ronald Reagan is alive but forgetting things. An elephant never forgets, but this is personal, not political. We must make that distinction or all our politicians would be institutionalized for forgetting their promises. -

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices

Childbearing in Japanese Society: Traditional Beliefs and Contemporary Practices by Gunnella Thorgeirsdottir A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Social Sciences School of East Asian Studies August 2014 ii iii iv Abstract In recent years there has been an oft-held assumption as to the decline of traditions as well as folk belief amidst the technological modern age. The current thesis seeks to bring to light the various rituals, traditions and beliefs surrounding pregnancy in Japanese society, arguing that, although changed, they are still very much alive and a large part of the pregnancy experience. Current perception and ideas were gathered through a series of in depth interviews with 31 Japanese females of varying ages and socio-cultural backgrounds. These current perceptions were then compared to and contrasted with historical data of a folkloristic nature, seeking to highlight developments and seek out continuities. This was done within the theoretical framework of the liminal nature of that which is betwixt and between as set forth by Victor Turner, as well as theories set forth by Mary Douglas and her ideas of the polluting element of the liminal. It quickly became obvious that the beliefs were still strong having though developed from a person-to- person communication and into a set of knowledge aquired by the mother largely from books, magazines and or offline. v vi Acknowledgements This thesis would never have been written had it not been for the endless assistance, patience and good will of a good number of people. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

Panelist Bios

PANELIST BIOGRAPHIES CATE ADAIR Catherine Adair was born in England, spent her primary education in Switzerland, and then returned to the UK where she earned her degree in Set & Costume Design from the University of Nottingham. After a series of apprenticeships in the London Theater, Catherine immigrated to the United States where she initially worked as a costume designer in East Coast theater productions. Her credits there include The Kennedy Center, Washington Ballet, Onley Theater Company, The Studio and Wolf Trap. Catherine then moved to Los Angeles, joined the West Coast Costume Designers Guild, and started her film and television career. Catherine’s credits include The 70s mini-series for NBC; The District for CBS; the teen film I Know What You Did Last Summer and Dreamworks’ Win a Date with Tad Hamilton. Currently Catherine is the costume designer for the new ABC hit series Desperate Housewives. ROSE APODACA As the West Coast Bureau Chief for Women's Wear Daily (WWD) and a contributor to W, Rose Apodaca and her team cover the fashion and beauty industries in a region reaching from Seattle to Las Vegas to San Diego, as well as report on the happenings in Hollywood and the culture-at-large. Apodaca is also instrumental in the many events and related projects tied to WWD and the fashion business in Los Angeles, including the establishment of LA Fashion Week, and has long been a champion of the local design community. Before joining Fairchild Publications in June 2000, Apodaca covered fashion and both popular and counter culture for over a decade for the Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Sportswear International, Detour, Paper and others. -

Halston, Netflix's New Series, Imagines How the Designer Created Halston

Halston, Netflix’s new series, imagines how the designer created Halston, his spectacularly successful 1975 fragrance. Grin or groan at the screenwriter’s fiction, the truth is much more interesting. Here is the real Halston story, an excerpt from AMERICAN LEGENDS, Michael Edwards’ new book coming out in Fall 2023. Twenty years in research, it traces the evolution of American perfumery thru forty legendary fragrances. By 1972, Halston’s business was grossing nearly $30 million in retail sales. That year, he won his fourth Coty Award and was acclaimed by Women’s Wear Daily as “one of the greats”. The elegance of the new American style was never more evident than at the couture show mounted in November 1973 to raise funds for the restoration of the Palace of Versailles. Five American designers - Bill Blass, Stephen Burrows, Halston, Anne Klein and Oscar de la Renta - joined five French couturiers in presenting their collections. The French used elaborate backdrops and props. The Americans used a bare stage and ten Black models. Their spare elegance put the French to shame. In late 1973, in a move that stunned the fashion industry, Halston sold his name, his company and his design services to David Mahoney of Norton Simon for sixteen million dollars. Norton Simon Inc. was one of the conglomerates stitched together in the 1960s. It owned such diverse interests as Hunt Food, Somerset Liquor, Avis Car Rental, Hartman Luggage and McCall Patterns. “We had also just bought the Max Factor cosmetic company,” said Dan Moriarty, then assistant to chairman of the board David Mahoney. -

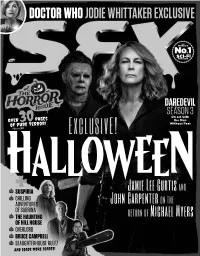

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

Claims Junta Beaten Earlier This Month, a 10-Year- the Hospital's Intensive Care Imlt

V. -A WEDNESDAY, JULY 21, 1971 PAGE THIRTY-TWO lSlanrl|(PBt?r. lEvraittg UmiUi Most Manchester Stores Open Tonight Until 9 O’Clock ed yesterday by Vernon PoUce /■ Hazards Cited V em on T eeii on a warrant issued by Circuit Average Daily Net Press Run Court 12 charging him with / The Weather breach of peace by asmult. Mmmmmmake For H m Week Ended Hurt in Fall The alleged incident happened Many Home Pools Violate ’ July 17, 1971 Fair tonight but early a.m. July 13 at a local business es fog developing; low In 60*. To From C liff tablishment. Building Code for Town ^upntnn Ulrrall) morrow clearing, becoming quite Arrested by warrant also on It a 1 5 ,0 0 0 warm; high near 90. the same charge was Gary WARNING — Swimming well. Failure to comply with the A Ifl-yearold Vernon youth Manchester— A City of Village Charm Bannon, 17, of 61 Park West pools may be hazardous to your building code is a misdemeanor who fell 80 feet over a cliff Sun health. — and each day the* pool is in Dr., Rockville. Both youths are day night in Lagiina, Calif., was According to the town build- violation is a separate offense, scheduled to appear in Circuit Restful Summer! VOL. LXXXX, NO. 248 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., THURSDAY, JULY 22, 1971 (CiMelfled Advertiatnc on Page 21) PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS described as in "very poor” con ing office, a considerable num- Any<me violating the code is Court, Rockville, Aug. 13. dition today by a spokesman ber of private swimming pools subject to a fine o f ‘up to $25 a Cook in or cook out, but select the foods that re from the South Coast Oommim- Wesley Hollister, 62, 346 Oak in violation of the town building day. -

The Russian Doll Stories

John clay SPIDERFINGERS The Russian doll Stories Photo of John Clay By Keira-Anee (additional post shoot treatment By Catherine Chambers) Copyright © John Clay 2020 All rights reserved The right of John Clay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 2 This is a work of fiction. Space and time have been rearranged to suit the convenience of the book, and with the exception of public figures, any resemblance to persons living or dead is coincidental. The opinions expressed are those of the characters and should not be confused with the author’s. 3 Index This Thing We Call A Foreword 10 ACT I 13 Chapter One: A Stage Called Shrewsbury 14 Chapter Two: The Voice 17 Chapter Three: Pretending to be David Shape 20 Chapter Four: Better Out Than In 26 Chapter Five: Magic Words 28 Chapter Six: Spiderfingers to the Rescue 31 Chapter Seven: Not Again 35 ACT II 40 Chapter Eight: They’ve Found You 41 Chapter Nine: Mine 45 Chapter Ten: There Is No Off The Radar 48 Chapter Eleven: The Sudden Conversion of Samson Owusu 53 Chapter Twelve: How The War Of The Gods Began 56 Chapter Thirteen: Spider Goes To Hollywood 60 Chapter Fourteen: A Night In The Life 63 ACT III 69 Chapter Fifteen: Far, Far Behind Me 70 Chapter Sixteen: Meeting The Cheerleader 73 Chapter Seventeen: Tend To Your Wounded 78 Chapter Eighteen: The Pseudologoi 81 Chapter Nineteen: How Do Your Powers Work? 83 Chapter Twenty: I’m Not the Bad Guy 88 Chapter Twenty One: The Best Weapons You Have Are In Your Mouth