Halston, Netflix's New Series, Imagines How the Designer Created Halston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

The Fashion Runway Through a Critical Race Theory Lens

THE FASHION RUNWAY THROUGH A CRITICAL RACE THEORY LENS A thesis submitted to the College of the Arts of Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Sophia Adodo March, 2016 Thesis written by Sophia Adodo B.A., Texas Woman’s University, 2011 M.A., Kent State University, 2016 Approved by ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Tameka Ellington, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Kim Hahn, Thesis Supervisor ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Amoaba Gooden, Committee Member ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Catherine Amoroso Leslie, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Linda Hoeptner Poling, Graduate Studies Coordinator, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Mr. J.R. Campbell, Director, The Fashion School ___________________________________________________________ Dr. Christine Havice, Director, The School of Art ___________________________________________________________ Dr. John Crawford-Spinelli, Dean, College of the Arts TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................................................................... iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Spring 2017 Arches 5 WS V' : •• Mm

1 a farewell This will be the last issue o/Arches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefton. On the cover: President EmeritusThomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. Conference Women s Basketball Tournament versus Lewis & Clark. After being behind nearly the whole —. game and down by 10 with 3:41 left in the fourth |P^' quarter, the Loggers start chipping away at the lead Visit' and tie the score with a minute to play. On their next possession Jamie Lange '19 gets the ball under the . -oJ hoop, puts it up, and misses. She grabs the rebound, Her second try also misses, but she again gets the : rebound. A third attempt, too, bounces around the rim and out. For the fourth time, Jamie hauls down the rebound. With 10 seconds remaining and two defenders all over her, she muscles up the game winning layup. The crowd, as they say, goes wild. RITE OF SPRING March 18: The annual Puget Sound Women's League flea market fills the field house with bargain-hunting North End neighbors as it has every year since 1968 All proceeds go to student scholarships. photojournal A POST-ELECTRIC PLAY March 4: Associate Professor and Chair of Theatre Arts Sara Freeman '95 directs Anne Washburn's hit play, Mr. Burns, about six people who gather around a fire after a nationwide nuclear plant disaster that has destroyed the country and its electric grid. For comfort they turn to one thing they share: recollections of The Simpsons television series. The incredible costumes and masks you see here were designed by Mishka Navarre, the college's costumer and costume shop supervisor. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

Panelist Bios

PANELIST BIOGRAPHIES CATE ADAIR Catherine Adair was born in England, spent her primary education in Switzerland, and then returned to the UK where she earned her degree in Set & Costume Design from the University of Nottingham. After a series of apprenticeships in the London Theater, Catherine immigrated to the United States where she initially worked as a costume designer in East Coast theater productions. Her credits there include The Kennedy Center, Washington Ballet, Onley Theater Company, The Studio and Wolf Trap. Catherine then moved to Los Angeles, joined the West Coast Costume Designers Guild, and started her film and television career. Catherine’s credits include The 70s mini-series for NBC; The District for CBS; the teen film I Know What You Did Last Summer and Dreamworks’ Win a Date with Tad Hamilton. Currently Catherine is the costume designer for the new ABC hit series Desperate Housewives. ROSE APODACA As the West Coast Bureau Chief for Women's Wear Daily (WWD) and a contributor to W, Rose Apodaca and her team cover the fashion and beauty industries in a region reaching from Seattle to Las Vegas to San Diego, as well as report on the happenings in Hollywood and the culture-at-large. Apodaca is also instrumental in the many events and related projects tied to WWD and the fashion business in Los Angeles, including the establishment of LA Fashion Week, and has long been a champion of the local design community. Before joining Fairchild Publications in June 2000, Apodaca covered fashion and both popular and counter culture for over a decade for the Los Angeles Times, USA Today, Sportswear International, Detour, Paper and others. -

Lucy F. Kweskin Matthew A. Skrzynski PROSKAUER ROSE LLP Eleven

20-12097-scc Doc 505 Filed 01/22/21 Entered 01/22/21 18:51:52 Main Document Pg 1 of 186 Hearing Date: February 12, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. (Prevailing Eastern Time) Objection Deadline: February 5, 2021 at 4:00 p.m. (Prevailing Eastern Time) Lucy F. Kweskin Jeff J. Marwil (admitted pro hac vice) Matthew A. Skrzynski Jordan E. Sazant (admitted pro hac vice) PROSKAUER ROSE LLP Brooke H. Blackwell (admitted pro hac vice) Eleven Times Square PROSKAUER ROSE LLP New York, New York 10036 70 West Madison, Suite 3800 Telephone: (212) 969-3000 Chicago, IL 60602 Facsimile: (212) 969-2900 Telephone: (312) 962-3550 Facsimile: (312) 962-3551 Peter J. Young (admitted pro hac vice) PROSKAUER ROSE LLP 2029 Century Park East, Suite 2400 Los Angeles, CA 90067-3010 Telephone: (310) 557-2900 Facsimile: (310) 557-2193 Attorneys for Debtors and Debtors in Possession UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK In re Chapter 11 CENTURY 21 DEPARTMENT STORES LLC, et al., Case No. 20-12097 (SCC) Debtors.1 (Jointly Administered) NOTICE OF APPLICATION OF DEBTORS FOR ENTRY OF AN ORDER AUTHORIZING THE EMPLOYMENT AND RETENTION OF BERDON LLP AS TAX PREPARER AND CONSULTANT EFFECTIVE AS OF THE PETITION DATE PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that a hearing (the “Hearing”) will be held on the Application of Debtors for Entry of an Order Authorizing the Employment and Retention of Berdon LLP as 1 The Debtors in these chapter 11 cases (the “Chapter 11 Cases”), along with the last four digits of each Debtor’s federal tax identification number, as applicable, are Century 21 Department Stores LLC (4073), L.I. -

(Roy Halston Frowick) (1932-1990) by Shaun Cole

Halston (Roy Halston Frowick) (1932-1990) by Shaun Cole Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The first international fashion superstar, Halston was a master of cut, detail, and finish. He dressed and befriended some of America's most glamorous women. Jackie Kennedy Onassis, Elizabeth Taylor, Babe Paley, Barbara Walters, Lauren Bacall, Bianca Jagger, and Liza Minnelli were just some of the women who wore Halston. Roy Halston Frowick was born on April 23, 1932 in Des Moines, Iowa, the second son of a Norwegian- American accountant with a passion for inventing. Roy developed an interest in sewing from his mother. As an adolescent he began creating hats and embellishing outfits for his mother and sister. Roy graduated from high school in 1950 then attended Indiana University for one semester. After the family moved to Chicago in 1952, he enrolled in a night course at the Chicago Art Institute and worked as a window dresser. Frowick's first big break came when the Chicago Daily News ran a brief story on his fashionable hats. In 1957 he opened his first shop, the Boulevard Salon, on Michigan Avenue. It was at this point that he began to use his middle name as his professional moniker. With the help of a lover twenty-five years his senior, celebrity hair stylist André Basil, Halston further developed his career by moving to New York later in 1957. Basil introduced Halston to milliner Lilly Daché, who offered him a job. Within a year he had been named co-designer at Daché, become the new best friend of several fashion editors and publishers, and left Daché's studio to become head milliner for department store Bergdorf Goodman. -

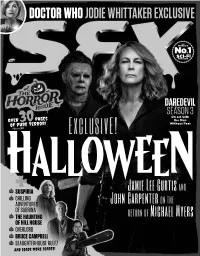

SFX’S Horror Columnist Peers Into If You’Re New to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones Movie

DOCTOR WHO JODIE WHITTAKER EXCLUSIVE SCI-FI 306 DAREDEVIL SEASON 3 On set with Over 30 pages the Man of pure terror! Without Fear featuring EXCLUSIVE! HALLOWEEN Jamie Lee Curtis and SUSPIRIA CHILLING John Carpenter on the ADVENTURES OF SABRINA return of Michael Myers THE HAUNTING OF HILL HOUSE OVERLORD BRUCE CAMPBELL SLAUGHTERHOUSE RULEZ AND LOADS MORE SCARES! ISSUE 306 NOVEMBER Contents2018 34 56 61 68 HALLOWEEN CHILLING DRACUL DOCTOR WHO Jamie Lee Curtis and John ADVENTURES Bram Stoker’s great-grandson We speak to the new Time Lord Carpenter tell us about new OF SABRINA unearths the iconic vamp for Jodie Whittaker about series 11 Michael Myers sightings in Remember Melissa Joan Hart another toothsome tale. and her Heroes & Inspirations. Haddonfield. That place really playing the teenage witch on CITV needs a Neighbourhood Watch. in the ’90s? Well this version is And a can of pepper spray. nothing like that. 62 74 OVERLORD TADE THOMPSON A WW2 zombie horror from the The award-winning Rosewater 48 56 JJ Abrams stable and it’s not a author tells us all about his THE HAUNTING OF Cloverfield movie? brilliant Nigeria-set novel. HILL HOUSE Shirley Jackson’s horror classic gets a new Netflix treatment. 66 76 Who knows, it might just be better PENNY DREADFUL DAREDEVIL than the 1999 Liam Neeson/ SFX’s horror columnist peers into If you’re new to the Netflix Catherine Zeta-Jones movie. her crystal ball to pick out the superhero shows, this third season Fingers crossed! hottest upcoming scares. is probably a bad place to start. -

White Webb Creates VIP Lounge at Studio 54

New York, NY (PRWEB) September 30, 2007 White Webb creates VIP lounge at Studio 54. Who said disco is dead? Thanks to those superfly guys at White Webb, it lives again at Studio 54. The former digs of the infamous dance club have been reborn as one of the funkiest theaters on Broadway thanks to the creative imaginings of The Roundabout Theatre Company. Originally an opera house, the building became notorious for its second life as the Big Apple’s most happening nightspot, Studio 54. Today, the Roundabout has replaced the dance floor debauchery with some of the world’s finest theater, but it hasn’t forgotten the building’s special history. In memory of the funk ‘n fantasy that cavorted within its walls, the Roundabout commissioned White Webb to bring back the disco beat. Seeking to create a lounge for its patrons, the Roundabout asked the design team to turn a long-forgotten basement space into Broadway’s classiest VIP room. Blending 70’s swank with modern luxe, White Webb’s design winks at Studio’s glory days while making every visitor feel like a coddled celebrity. Among the room’s ostrich walls, leopard carpeting, and luxurious velvet-covered banquettes, one wouldn’t be surprised to see Bianca Jagger (well, maybe Lindsay Lohan) riding in on a white horse. As the piece-de-resistance, White Webb designed a resplendent sculpture made of forged iron, gold balls and magnifying glasses. Commanding center stage in the room, the artwork evokes a huge sunburst – just what every room needs to be a true disco inferno! So how do you get past the velvet ropes? It’s not hard at all. -

Bare Witness

are • THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART "This is a backless age and there is no single smarter sunburn gesture than to hm'c every low-backed cos tume cut on exactly the same lines, so that each one makes a perfect frame for a smooth brown back." British Vogue, July 1929 "iVladame du V. , a French lady, appeared in public in a dress entirely a Ia guil lotine. That is to say ... covered with a slight transparent gauze; the breasts entirely bare, as well as the arms up as high as the shoulders.... " Gemleman's A·1agazine, 1801 "Silk stockings made short skirts wearable." Fortune, January 1932 "In Defence ofSh** ld*rs" Punch, 1920s "Sweet hem·ting matches arc very often made up at these parties. It's quite disgusting to a modest eye to see the way the young ladies dress to attract the notice of the gentlemen. They are nearly naked to the waist, only just a little bit of dress hanging on the shoulder, the breasts are quite exposed except a little bit coming up to hide the nipples." \ Villiam Taylor, 1837 "The greatest provocation oflust comes from our apparel." Robert Burton, Anatomy ofi\Jelancholy, 1651 "The fashionable woman has long legs and aristocratic ankles but no knees. She has thin, veiled arms and fluttering hands but no elbows." Kennedy Fraser, The Fashionahlc 1VIind, 1981 "A lady's leg is a dangerous sight, in whatever colour it appears; but, when it is enclosed in white, it makes an irresistible attack upon us." The Unil'ersol !:lpectator, 1737 "'Miladi' very handsome woman, but she and all the women were dccollctees in a beastly fashion-damn the aristocratic standard of fashion; nothing will ever make me think it right or decent that I should see a lady's armpit flesh-folds when I am speaking to her." Georges Du ~ - laurier, 1862 "I would need the pen of Carlyle to describe adequately the sensa tion caused by the young lady who first tr.od the streets of New York in a skirt ..