Terminal Man First Appeared in Slightly Different from in Playboy Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 10 Tossups 1. This Person Is Deemed

2008 TRASH Regionals Round 10 Tossups 1. This person is deemed superior to both Francesca in the Guggenheim and a social psychology professor in Baskin- Robbins. She likes her Scotch aged eighteen years. Her name is Janine, although she doesn't want to be called that. She has been encountered in a car by the side of the road, in a tub, and on a pool table, with the latter fulfilling her paramour's prom night pact. John, played by John Cho, popularized the term "MILF" in describing, for ten points, what older woman played by Jennifer Coolidge, the lover of Finch in the American Pie movies? Answer: Stifler's Mom or Mrs. Stifler (accept Janine Stifler on early buzz) 2. His 1984 graphical text adventure, Amazon, sold 100,000 copies. A personal friend of Jasper Johns, he published an appreciation of his work, as well as a book on BASIC programming, Electronic Life. Hollywood work included the script for Extreme Close Up as well as directing Looker and Physical Evidence. His pen names included Michael Lange, a pun on the German word for "tall", and Jeffrey Hudson, the name of a 17th century dwarf, under which he wrote A Case of Need. For ten points, name this author of The Terminal Man, Congo, and State of Fear, who recently died of cancer at the age of 66. Answer: Michael Crichton 3. This show's second episode, "Birdcage," featured a cameo by Audrina Partridge from The Hills. The third, "Dosing," sees the staff's bonus checks held hostage to a feud between the general manager, Neal, and HR director Rhonda, which is defused when the owner's wife tries to seduce Neal. -

Abbey, Cherie D., Ed. Biography Today: Author Series. Profil

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 434 064 SO 031 051 AUTHOR Harris, Laurie Lanzen, Ed.; Abbey, Cherie D., Ed. TITLE Biography Today: Author Series. Profiles of People of Interest to Young Readers. Volume 5, 1999. ISBN ISBN-0-7808-0372-8 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 194p. AVAILABLE FROM Omnigraphics, Inc., 2500 Penobscot Building, Detroit, MI 48226; Tel: 800-234-1340 (Toll Free). PUB TYPE Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Authors; Biographies; Childrens Literature; Elementary Secondary Education; Language Arts; *Popular Culture; Profiles; Reading Interests; Recreational Reading; Social Studies; Student Interests; *Supplementary Reading Materials IDENTIFIERS *Biodata; *Illustrators; Writing for Children ABSTRACT As with the regular issues of "Biography Today," this special subject volume on "Authors" was created to appeal to young readers in a format they can enjoy reading and readily understand. Each volume contains alphabetically-arranged sketches. Each entry in the volume provides at least one picture of the individual profiled, and bold-faced rubrics lead readers to information on birth, youth, early memories, education, hobbies, and honors and awards. Each entry ends with a list of easily accessible sources designed to lead the student to further reading on the individual and a current address. Obituary entries are also included and clearly marked in both the table of contents and at the beginning of the entry. Ten authors are profiled in this volume:(1) Sharon Creech;(2) Michael Crichton;(3) Karen Cushman;(4) Tomie dePaola;(5) Lorraine Hansberry;(6) Karen Hesse; (7) Brian Jacques;(8) Gary Soto;(9) Richard Wright; and (10) Laurence Yep. A series of general, places of birth, and birthday indexes is included. -

Michael Crichton Next Pdf

Michael crichton next pdf Continue Want more? Advanced embedding details, examples and help! Author: Michael CrichtonOriginal Title: NextBook Format: HardcoverNumber Pages: 431 PagesFirst published in: November 28, 2006Clean edition: November 28, 2006ISBN Number: 9780060872984Language: Englishcategory: Fiction, science fiction, thriller, seductionForms: ePUB (Android), sound mp3, audiobook and Kindle. The translated version of this book is available in Spanish, English, Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Bengali, Arabic, Portuguese, Indonesian/Malaysian, French, Japanese, German and many others for free download. Please note that the tricks or techniques listed in this PDF are either fictional or claimed to be the work of its creator. We do not guarantee that these methods will work for you. Some of the methods listed in Next may require a good knowledge of hypnosis, users are advised to either leave these sections or should have a basic understanding of the subject before practicing them. DMCA and Copyright: The book is not hosted on our servers to remove the file, please contact the url of the source. If you see a Google Drive link instead of the source URL, it means that the witch file you receive after approval is just a summary of the original book or the file has already been deleted. Author: Michael Crichton Origin Title: TimelineBook Format: Mass Market PaperbackNumber Pages: 489 pagesFirst Published in: November 16, 1999Latist Edition: June 2000ISBN Number: 978009924721Language: Englishgorcatey: Fiction, science fiction, thriller, science fiction, time travel, historical, historical fiction, seductionForma: ePUB (Android), sound mp3, audiobook and Kindle. The translated version of this book is available in Spanish, English, Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Bengali, Arabic, Portuguese, Indonesian/Malaysian, French, Japanese, German and many others for free download. -

An Agricultural Law Research Article Regulating Agricultural Biotech

University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture [email protected] $ (479) 575-7646 An Agricultural Law Research Article Regulating Agricultural Biotech Research: An Introductory Perspective by James B. Wadley Originally published in HAMLINE LAW REVIEW 12 HAMLINE L.R. 569 (1989) www.NationalAgLawCenter.org REGULATING AGRICULTURAL BIOTECH RESEARCH: AN INTRODUCTORY PERSPECTIVE James B. Wadley* Introduction In June 1816, Mary Shelly penned a novel while at the Villa Di odati near Geneva, Switzerland.l The novel, Frankenstein: The Modern Prometheus, was the product of a nightmare suffered by Mary while she was engaged in a storytelling competition with her twenty-year-old husband, Percy Bysshe Shelly, her stepsister Claire Clarement, Lord Byron and John Polidori. On the particular night the idea occurred to her, she had been listening to Byron and Shelly argue over the origin of life and speculate whether it could be artificially created. Although man has been intrigued with the possibility of creating new lifeforms, Mary's creation of Frankenstein's monster seems to encapsulate the nightmares and fears of us all that man might actually succeed in his quest and in the process unleash upon the world an uncontrollable force that might spell its doom. That such a thing could be accomplished through re-engineering of biologic processes has been a favorite theme of the science-fiction/ horror movie makers. 2 As a child I remember that one of my own fa vorite horror movies was The Beginning of the End in which grasshop pers that had eaten irradiated tomatoes in a scientist's greenhouse be came gargantuan and escaped to wreak havoc upon Chicago. -

JOSE DELGADO: a CASE STUDY Science, Hubris, Nemesis

JOSE DELGADO: A CASE STUDY Science, Hubris, Nemesis and Redemption By Barry Blackwell, M.A, M.Phil, MB, BChir., M.D., FRCPsych. International Network for the History of Neuropsychopharmacology 2014 1 Jose Delgado: A Case Study; Science, Hubris, Nemesis and Redemption Long, long before men and women became scientists the Greek playwrights portrayed the justice meted out toward the overweening pride and ambition of their heroes by the Gods’ wrath and retribution. Hubris invited nemesis and only rarely was there hope of redemption. Nothing Freud or the analysts added altered this dynamic as the following case study from the twentieth century illustrates. The Case Jose Manuel Rodriguez Delgado (1915-2011) This biography has an unusual provenance and was not something I might have anticipated writing. Born almost twenty years after Delgado at the beginning of the neuropsychopharmacology era I was not familiar with his pioneering work in physiology using electrode implants in animals and humans to modify emotion and behavior. It might have crossed my horizon during psychiatric training (1962 – 1967) at a time when his research began attracting international attention but I was too immersed in my own animal pharmacology studies to take serious note. Jose emigrated from Spain to the USA in 1950 and spent 20 years in America before returning to Spain when controversy engulfed his career. Based on his pioneering work at Yale University he was among the small number of clinical and animal researchers who became founding members of the ACNP in 1961. Although we were fellow members for most of our careers our paths never crossed; neither of us served on any of the organization’s committees or held office nor did he receive any of its awards. -

Surgery for Psychiatric Disorders

Neurosurg Clin N Am 14 (2003) xiii–xiv Preface Surgery for psychiatric disorders Ali R. Rezai, MD Steven A. Rasmussen, MD Benjamin D. Greenberg, MD, PhD Guest Editors Surgery for psychiatric disorders has intrigued negative effects on marital, parental, social, voca- the psychiatric, neurological, and neurosurgical tional, and other life functions. communities as well as the lay public for the past Advances in the efficacy, safety, and tolerabi- 70 years. Few other therapies have generated such lity of treatments for OCD and depression have controversy, enthusiasm, misconception, and, at been made in the past 20 years. However, a signif- times, indiscriminate use. Recent advances in image icant number of patients with OCD and major guidance, devices, and stereotactic procedures, as depression refractory to nonsurgical treatments well as rapid expansion of our knowledge of the remain severely ill. These individuals, who are liv- functional neuroanatomy of the major psychiatric ing lives of hopeless desperation, may ultimately disorders has led to renewed interest in neurosurgi- face the tragic end of suicide. The hope that sur- cal approaches to these conditions. This issue of gery can offer relief to these patients from agony the Neurosurgery Clinics of North America was and suffering is the fundamental imperative that envisioned with the purpose of compiling the demands ongoing research in this area. perspectives of experts on the cutting edge of It is clear that psychiatric neurosurgery research in the neurosurgical treatment of psychi- will undergo a rapid evolution over the next atric disorders. decade. Today, dedicated multidisciplinary teams Currently, the two most common psychiatric specializing in treating psychiatric patients have disorders amenable to surgical intervention are at their disposal the entire spectrum of modern obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and major functional neurosurgical techniques, including depression. -

Five Patients in 50 Years: Revisiting the Speculations of Michael Crichton’S Medical School Nonfiction

Five Patients in 50 years: Revisiting the speculations of Michael Crichton’s medical school nonfiction Tyler D. Barrett, MA, MPS Tyler Barrett is an Assessment Clinician at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute, Seattle, WA. “We’re talking about what the future is; no one knows what the future is!” – Michael Crichton, 20071 uthor Michael Crichton (1942-2008) crafted con- vincing stories of speculative science and tech- nology into Hollywood blockbusters and wide Acommercial success. Throughout his career, he leveraged his medical education to construct an identity as an au- thority on science. In merging facts and scientific processes with plausible speculation, he earned a reputation for fore- sight intermittently at odds with scientific accuracy. By December 1969, the 27-year-old Crichton had al- picture industry for film adaptation. Among them was ready written 10 novels, published mostly under pseud- The Andromeda Strain, which became a New York Times onyms from the 1960s to early 1970s. Three of the Best Seller. By his own admission, Crichton was enjoy- novels had recently been purchased by the motion ing his success and recognition as an author, with trips 8 The Pharos/Winter 2021 to Hollywood and meetings with high-profile entertain- was followed by two additional Lange potboilers, and a ment executives.2. He was, at the time, also a fourth-year crime fiction collaboration with his brother under the medical student at Harvard completing clinical rotations alias Michael Douglas. at Massachusetts General Hospital. When he did return to publishing as Michael Crichton, in 1970, it was for Five Patients: The Hospital Explained, Medical school bookends a work of educative nonfiction interspersed with specu- Crichton’s experiences in medical school were both lation. -

Filozofická Fakulta Univerzity Palackého

Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Palackého Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Themes and Conflicts in Michael Crichton’s Novels Bakalářská práce Autor: Jan David (Anglická – Německá filologie) Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Libor Práger Olomouc 2012 Prohlašuji, že jsem tuto bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a uvedl úplný seznam citované a použité literatury. V Olomouci dne 17.8.2012 ___________________________ Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Biography of Michael Crichton and the Influences of His Life on His Literary Career .... 3 2.1 Michael Crichton’s Life ............................................................................................... 3 2.2 Influences on Michael Crichton’s Work and Choice of Themes ................................ 6 2.2.1 Childhood and Undergraduate College Experience ............................................. 6 2.2.2 Studies at Harvard Medical School ...................................................................... 6 2.2.3 Making Movies .................................................................................................... 8 2.2.4 Traveling .............................................................................................................. 9 2.2.5 Contact with Psychic Powers ............................................................................. 10 3. Themes and Conflicts in Michael Crichton’s Works ....................................................... -

N1i19 Briefing Book

INCIDENT N1I19 N1I19 BRIEFING BOOK INCIDENT N - 01 - I - 019 INCIDENT AND ANALYSIS WITH SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL COVERING THE TIME LINE 67-070 THRU 73-013 INCLUDING INVESTIGATIVE REPORT [C] 1983 BY W. C. VETSCH SECTION ONE - TIME LINE PERIOD ONE 003 PERIOD TWO 017 PERIOD THREE 023 PERIOD FOUR 027 INCIDENT N1I19 PERIOD FIVE 030 PERIOD SIX 036 PERIOD SEVEN 040 PERIOD EIGHT 051 PERIOD NINE 054 PERIOD TEN 055 N1I19 RELATED INCIDENTS 057 SECTION TWO - CASE HISTORIES THE PSYCHIATRIST 060 G E HERNDON 061 Q-273 063 MAGGIE 064 R WALTON 065 INCIDENT N1I19 THE ELECTRICIAN 067 MR. KENNEDY 067 THE NYMPHOMANIAC 068 EDWARD 068 THE SOLDIER 069 THE GIRL FROM LSU 070 THE GIRL WITH THE SCAR 071 CLAUDIA 071 SECTION THREE - STAFF DOSSIERS POLICY STATEMENT 074 PATRICIA B. WEST 074 DEARMAN 075 JAMES HENRY 075 BILLY GRAHAM 077 WILLIAM CHRISTIAN SUPER 077 CHARLOTTE LAMAR 079 INCIDENT N1I19 PHILIP A. SCHAEFER 079 W. L. WAALS 080 MARY JANE ALEXANDER 081 RALPH WELLS BUDDINGTON 082 JOYCE JEAN LEMMONS 083 DR & MRS METZ 083 MARTHA WICKETT 084 WALKER 084 SEVERENCE KELLY 085 J. B. LA ROSE 086 SECTION FOUR - SETS CHARITY HOSPITAL OF NEW ORLEANS (HB5) 087 SOUTHEAST LOUISIANA HOSPITAL (HB6) 095 SOUTHEASTERN M H CLINIC (HB7) 105 EAST LOUISIANA HOSPITAL (HB9) 111 SECTION FIVE - DRUGS AND OTHER TREATMENTS INCIDENT N1I19 INTRODUCTION 123 OBSOLETE PROCEDURES 124 MELLARIL 125 THORAZINE 127 STELAZINE 129 HALDOL 130 PROLIXIN 131 LSD-25 133 FUTURE SHOCK 135 ANTI PSYCHOTIC DRUGS 136 SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON DRUGS 137 THE SECRET OF THE MAJOR TRANQUILIZERS 140 THE METAPHYSICS OF THE MAJOR TRANQUILIZERS 140 SUMMARY 142 SECTION SIX - LAW THE MENTAL HOSPITAL SYSTEM AND CIVIL RIGHTS 143 ORIGIN OF THE "OLD LAW" 146 THE "OLD LAW" IN PRACTICE 147 ORIGIN OF THE "NEW LAW" 151 THE "NEW LAW" IN PRACTICE 151 THE 1978-1979 LA. -

The Beatification of Chris Mccandless: from Thieving Poacher Into Saint

Opinions The beatification of Chris McCandless: From thieving poacher into saint Author: Craig Medred Updated: September 27, 2016 Published September 20, 2013 Thanks to the magic of words -- and words can indeed be magic -- the poacher Chris McCandless was transformed in his afterlife into some sort of poor, admirable romantic soul lost in the wilds of Alaska, and now appears on the verge of becoming some sort of beloved vampire. Given the way things are going, the dead McCandless is sure to live on longer than the live McCandless, who starved to death in Interior Alaska because he wasn't quite successful enough as a poacher. Alaska moose hunters in August 1992 found the remains of his 67-pound body in a sleeping bag in a deserted bus not far off the George Parks Highway west of Healy. Author Jon Krakauer later immortalized McCandless in the 1996 book "Into the Wild," conspired with director Sean Penn to bring him back to life again in the 2007 movie of the same name, and is now playing the media to resurrect McCandless once more with a new theory as to how the 24-year-old died. Since Krakauer, the maker of the literary magic and a man who seems interested in nothing in life so much as book sales, wants to revisit his defining character, isn't it about time for a painful and objective public consideration of the real McCandless, given that he has now been dead long enough that no one really needs to play nice about his behaviors preceding his death. -

Open Jenelljohnsondissertation.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts ECHOES OF THE SOUL: A RHETORICAL HISTORY OF LOBOTOMY A Dissertation in English by Jenell M. Johnson Copyright 2008 Jenell M. Johnson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2008 The dissertation of Jenell M. Johnson was reviewed and approved* by the following: Susan Merrill Squier Brill Professor of Women’s Studies and English Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Michael Bérubé Paterno Family Professor of English Rosa Eberly Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and English Stephen H. Browne Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Robin Schulze Professor of English Head of the English Department *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract Using critical techniques drawn from rhetorical studies, science studies, and cultural studies, Echoes of the Soul: A Rhetorical History of Lobotomy examines one of the most controversial chapters in American medicine by analyzing its rhetorical life in biomedical and popular discourses. Rather than divide these sites of discursive production, this project uses their points of articulation to explore the reciprocal relationship between biomedicine and other forms of culture. Echoes of the Soul first argues for the contribution of a rhetorical perspective to the history of medicine, and then presents lobotomy as a compelling case study. Chapter 2 troubles the demarcation between clinical practice and biomedical research by analyzing the arguments for lobotomy’s contribution to neurophysiology in Walter Freeman and James Watts’ Psychosurgery (1942). The next two chapters trace lobotomy’s rise and fall in American medicine by positioning this trajectory next to the shifting evaluation of the operation in popular discourse from the mid-1930s to the mid-1950s. -

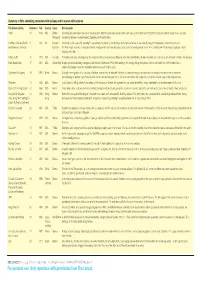

For Personal Use. Only Reproduce with Permission from the Lancet

Summary of films containing characters with epilepsy and/or scenes with seizures Film (Release Date) Reference Year Country Genre Brief Synopsis 1900 15 1976 Italy Drama Set in Italy, this epic follows the lives of two boys from different social classes born on the same day, over the first half of the 20th Century. A prostitute experiences a seizure (Historical) sandwiched between a naked Gerard Depardieu and Robert DeNiro. A Matter of Life and Death 5 1946 UK Romantic An airman is shot down after donating his parachute to his friend. As his life hangs in the balance he tries to persuade the angels in the heavenly realm that he should (aka Stairway to Heaven) Comedy live. Each angel encounter is associated with a simple partial seizure (an olfactory sensation) and a complex partial seizure in the earthly realm. No mention of epilepsy is made throughout the film. A Wedding** 16 1978 USA Comedy On hearing bad news, a teenage boy has a seizure, but then recovers immediately once the misunderstanding has been resolved. John Considine, one of the film’s writers, has epilepsy. Black Hawk Down 17 2001 USA Action (War) Graphic war drama detailing a dangerous US mission in Somalia in 1993. While waiting in the hanger, during the build up to the vicious battle one of the soldiers has a seizure. This seizure is also documented in a factual account of the mission. Capitalismo Selvagem) 18 1993 Brazil Drama During the investigation of his company, a Brazilian journalist has an affair with the head of a wealthy mining corporation who has epilepsy and whose wife is presumed dead following an airplane crash.