The Science of Michael Crichton : an Unauthorized Exploration Into the Real Science Behind the Fic- Tional Worlds of Michael Crichton / Edited by Kevin R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note to Users

NOTE TO USERS Page(s) not included in the original manuscript are unavailable from the author or university. The manuscript was microfilmed as received 88-91 This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. AccessinglUMI the World’s Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Mi 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8820263 Leigh Brackett: American science fiction writer—her life and work Carr, John Leonard, Ph.D. -

Struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld

WiN: The EAAS Women’s Network Journal Issue 2 (2020) Skin-Deep Gender: Posthumanity and the De(con)struction of the Feminine/Masculine Dichotomy in Westworld Amaya Fernández Menicucci ABSTRACT: This article addresses the ways in which gender configurations are used as representations of the process of self-construction of both human and non-human characters in Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy’s series Westworld, produced by HBO and first launched in 2016. In particular, I explore the extent to which the process of genderization is deconstructed when human and non-human identities merge into a posthuman reality that is both material and virtual. In Westworld, both cyborg and human characters understand gender as embodiment, enactment, repetition, and codified communication. Yet, both sets of characters eventually face a process of disembodiment when their bodies are digitalized, which challenges the very nature of identity in general and gender identity in particular. Placing this digitalization of human identity against Donna Haraway’s cyborg theory and Judith Butler’s citational approach to gender identification, a question emerges, which neither Posthumanity Studies nor Gender Studies can ignore: can gender identities survive a process of disembodiment? Such, indeed, is the scenario portrayed in Westworld: a world in which bodies do not matter and gender is only skin-deep. KEYWORDS: Westworld; gender; posthumanity; embodiment; cyborg The cyborg is a creature in a post-gender world. The cyborg is also the awful apocalyptic telos of the ‘West’s’ escalating dominations . (Haraway, A Cyborg Manifesto 8) Revolution in a Post-Gender, Post-Race, Post-Class, Post-Western, Posthuman World The diegetic reality of the HBO series Westworld (2016-2018) opens up the possibility of a posthuman existence via the synthesis of individual human identities and personalities into algorithms and a post-corporeal digital life. -

Beyond Westworld

“We Don’t Know Exactly How They Work”: Making Sense of Technophobia in 1973 Westworld, Futureworld, and Beyond Westworld Stefano Bigliardi Al Akhawayn University in Ifrane - Morocco Abstract This article scrutinizes Michael Crichton’s movie Westworld (1973), its sequel Futureworld (1976), and the spin-off series Beyond Westworld (1980), as well as the critical literature that deals with them. I examine whether Crichton’s movie, its sequel, and the 1980s series contain and convey a consistent technophobic message according to the definition of “technophobia” advanced in Daniel Dinello’s 2005 monograph. I advance a proposal to develop further the concept of technophobia in order to offer a more satisfactory and unified interpretation of the narratives at stake. I connect technophobia and what I call de-theologized, epistemic hubris: the conclusion is that fearing technology is philosophically meaningful if one realizes that the limitations of technology are the consequence of its creation and usage on behalf of epistemically limited humanity (or artificial minds). Keywords: Westworld, Futureworld, Beyond Westworld, Michael Crichton, androids, technology, technophobia, Daniel Dinello, hubris. 1. Introduction The 2016 and 2018 HBO series Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy has spawned renewed interest in the 1973 movie with the same title by Michael Crichton (1942-2008), its 1976 sequel Futureworld by Richard T. Heffron (1930-2007), and the short-lived 1980 MGM TV series Beyond Westworld. The movies and the series deal with androids used for recreational purposes and raise questions about technology and its risks. I aim at an as-yet unattempted comparative analysis taking the narratives at stake as technophobic tales: each one conveys a feeling of threat and fear related to technological beings and environments. -

Between Technophobia and Futuristic Dreams. Visions of the Possible Technological Development in Black Mirror and Westworld Series

Agnieszka Kiejziewicz Between technophobia and futuristic dreams. Visions of the possible technological development in Black Mirror and Westworld series Jagiellonian University Introduction The dualism in perceiving the technology on the Western ground, not only as a blessing connected with the rapid development of the civilization but also as a possible reason for the future fall of the humanity, can be dated back to the literary works such as Frankenstein (1818) by Marry Shelley, dystopian Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley (1894–1963)1 or Fritz Lang’s filmMetropolis (1927). However, it was no sooner than in the late 1950s when the discourse about the influence of technology on the society appeared in numerous forms of art. The writers such as William Burroughs (1914–1997)2, Phillip K. Dick (1928–1982)3 or the techno-prophet Marshall McLuhan (1918–1980)4 observed that to extend their perception, sensations and abilities, people cling to technology represented by various devices, what brings the humanity closer to the apocalypse the overused technology is to cause. The inspiration of the findings provided by the theorists in 1 See: Bloom, Harold, ed. Aldous Huxley. New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2010. 2 See: Hibbard, Allen. Conversations with William S. Burroughs. Jackson: University Press of Missis- sippi, 1999. W. Burroughs, alongside Jack Kerouack and Allen Ginsberg was a distinctive figure of the Beat Generation. He was the author of the novels as, later filmed by David Cronenberg,Naked Lunch (1959) or The Nova Trilogy (1961-1967), many short stories and non-fictional contributions. 3 See: Palmer, Christopher. -

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of Fc Available for $4.00 From: TRISKELL PRESS P

FANTASY FAIRE 19 81 of fc Available for $4.00 from: TRISKELL PRESS P. 0. Box 9480 Ottawa, Ontario Canada K1G 3V2 J&u) (B.Mn'^mTuer KOKTAL ADD IHHOHTAl LOVERS TRAPPED Is AS ASCIEST FEUD... 11th ANNUAL FANTASY FAIRS JULY 17, 18, 19, 1981 AMFAC HOTEL MASTERS OF CEREMONIES STEPHEN GOLDIN, KATHLEEN SKY RON WILSON CONTENTS page GUEST OF HONOR ... 4 ■ GUEST LIST . 5 WELCOME TO FANTASY FAIRE by’Keith Williams’ 7 PROGRAM 8 COMMITTEE...................... .. W . ... .10 RULES FOR BEHAVIOR 10 WALKING GUIDE by Bill Conlln 12 MAP OF AREA ........................................................ UPCOMING FPCI CONVENTIONS 14 ADVERTISERS Triskell Press Barry Levin Books Pfeiffer's Books & Tiques Dangerous Visions Cover Design From A Painting By Morris Scott Dollens GUEST OF HONOR FRITZ LEIBER was bom in 1910. Son of a Shakespearean actor, Fritz was at one time an actor himself and a mem ber of his father’s troupe. He made a cameo appearance in the film "Equinox." Fritz has studied many sciences and was once editor of Science Digest. His writing career began prior to World War 11 with some stories in Weird Tales. Soon Unknown published his novel "Conjure Wife, " which was made into a movie under the title (of all things) "Bum, Witch, Bum!" His Gray Mouser stories (which were the inspira tion for the Fantasy Faire "Fritz Leiber Fantasy Award") were started in Unknown and continued in Fantastic, which magazine devoted its entire Nov., 1959 issue to Fritz's stories. In 1959 Fritz was awarded a Hugo, by the World Science Fiction Convention for his novel "The Big Time." His novel "The Wanderer," about an interloper into our solar system, won the Hugo again in 1965.'-His novelettes Gonna Roll the Bones," "Ship of Shadows" and "Ill Met in Lankhmar” won the Hugo in 1968, 1970 and 1971 in that order. -

There Is More Than 3TG the Need for the Inclusion of All Minerals in EU Regulation for Conflict Due Diligence

There is more than 3TG The need for the inclusion of all minerals in EU regulation for conflict due diligence SOMO Paper | January 2015 Companies that use minerals in their products risk International standards and regulation contributing to conflict financing or human rights abuses via their mineral supply chains, especially if upstream Normative standards suppliers are located in conflict zones. This problem is Under the European Convention on Human Rights and being addressed by the European Commission (EC), international human rights law, European member states which has proposed a new regulation with a voluntary have an obligation to ensure that business enterprises due diligence framework to address the risk of financing operating within their jurisdiction do not cause or armed groups and security forces, and mitigate other contribute to human rights violations. The United Nations adverse impacts associated with the extraction, transport Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP) and trade of four particular minerals: tin, tantalum, and the Organisation for Economic Development and tungsten and gold (3TG). Cooperation’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD Guidelines) set clear standards for business enter- This briefing paper discusses one specific issue in the prises to respect human rights, conduct human rights due proposed EC regulation – the limited number of conflict diligence and implement measures to prevent, address and minerals it includes. It puts the case that the decision to redress any human rights violations.1 The UNGP prescribe focus on the import of minerals and metals containing or that states need to “ensure that their current policies, consisting of 3TG is arbitrary and far too limited to achieve legislation, regulations and enforcement measures are the proposal’s objective of reducing the financing of armed effective in addressing the risks of business involvement groups and security forces through mineral proceeds in in gross human rights abuses”.2 The UNGP have special conflict-affected and high-risk areas. -

Niven Ring Gravitational Stability Carl A

Niven Ring Gravitational Stability Carl A. Brannen 8500 148th Ave. NE #T-1064, Redmond, WA USA, [email protected] Abstract. A “Niven ring” is a ring of material placed around a star so as to provide a very large inhabitable region. The ring would be solid, about a million miles wide and would be at about earth’s orbit, around 100 million miles from the sun. The ring would be set spinning so that it would provide an equivalent to earth’s gravity field by the action of centrifugal force. Walls a thousand miles high along the edges hold in the atmosphere. The origin of the Niven ring idea is L. Niven’s 1970 novel “Ringworld”. Sometime after writing this book, the author was informed that a Niven ring would be gravitationally unstable. This resulted in further plot development by the author in his 1980 novel, “The Ringworld Engineers”, which describes the efforts necessary to keep the Niven ring orbiting stably. In this short paper we derive the gravitational instability of a Niven ring without calculus. We show that the ring orbit decays exponentially with a time period t of about two months. Keywords: Larry Niven, Ringworld, stability, engineer PACS: 96.15.De, 12.10.Dm 1. INTRODUCTION Larry Niven’s book “Ringworld” [1] describes what is now known as a “Niven ring”, a ring of material surrounding a star at a comfortable (for life) distance, and set in motion so as to provide centrifugal acceleration equivalent to earth’s gravitational field. The orbit of a planet in the gravitational field of the sun is stable, that is, if we make small changes to the orbital parameters this will result in only small changes to the orbit of the planet. -

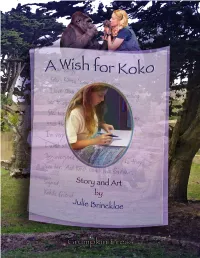

Finding Koko

1 A Wish for Koko by Julie Brinckloe 2 This book was created as a gift to the Gorilla Foundation. 100% of the proceeds will go directly to the Foundation to help all the Kokos of the World. Copyright © by Julie Brinckloe 2019 Grumpkin Press All rights reserved. Photographs and likenesses of Koko, Penny and Michael © by Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation Koko’s Kitten © by Penny Patterson, Ron Cohn and the Gorilla Foundation No part of this book may be used or reproduced in whole or in part without prior written consent of Julie Brinckloe and the Gorilla Foundation. Library of Congress U.S. Copyright Office Registration Number TXu 2-131-759 ISBN 978-0-578-51838-1 Printed in the U.S.A. 0 Thank You This story needed inspired players to give it authenticity. I found them at La Honda Elementary School, a stone’s throw from where Koko lived her extraordinary life. And I found it in the spirited souls of Stella Machado and her family. Principal Liz Morgan and teacher Brett Miller embraced Koko with open hearts, and the generous consent of parents paved the way for students to participate in the story. Ms. Miller’s classroom was the creative, warm place I had envisioned. And her fourth and fifth grade students were the kids I’d crossed my fingers for. They lit up the story with exuberance, inspired by true affection for Koko and her friends. I thank them all. And following the story they shall all be named. I thank the San Francisco Zoo for permission to use my photographs taken at the Gorilla Preserve in this book. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

THIS IS CONGO a Film by Daniel Mccabe

PRESENTS THIS IS CONGO A film by Daniel McCabe Running Time: 91 minutes Language: English, French, Swahili and Lingala with English subtitles The Democratic Republic of the Congo / United States / Canada PRESS CONTACT: SALES CONTACT: Dogwoof. Dogwoof Yung Kha +44(0)20 7253 6244 Ana Vicente +44 7977 051577 CONFIDENTIAL: The information contained in this document may contain confidential information and is intended only for the individual(s) or entity(ies) to whom it is addressed. The information contained in this document may also be protected by legal privilege, federal law or other applicable law. Any distribution, dissemination or duplication of this docu- ment is strictly prohibited. SYNOPSIS Why is it that some countries seem to be continually mired in cyclical wars, political instability and economic crises? The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one such a place, a mineral-rich Central African country that, over the last two decades, has seen more than five million conflict-related deaths, multiple regime changes and the wholesale impoverishment of its people. Yet though this ongoing conflict is the world’s bloodiest since WWII, little is known in the West about the players or stakes involved. THIS IS CONGO provides an immersive and unfiltered look into the Africa’s longest continuing conflict and those who are surviving within it. By following four compelling characters — a whistleblower, a patriotic military commander, a mineral dealer and a displaced tailor — the film offers viewers a truly Congolese perspective on the problems that plague this lushly beautiful nation. Colonel ‘Kasongo’, Mamadou Ndala, Mama Romance and Hakiza Nyantaba exemplify the unique resilience of a people who have lived and died through the generations due to the cycle of brutality generated by this conflict. -

An Interview with John Gurdon Aidan Maartens*,‡

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Development (2017) 144, 1581-1583 doi:10.1242/dev.152058 SPOTLIGHT An interview with John Gurdon Aidan Maartens*,‡ John Gurdon is a Distinguished Group Leader in the Wellcome Trust/ Cancer Research UK Gurdon Institute and Professor Emeritus in the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge. In 2012, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with Shinya Yamanaka for work on the reprogramming of mature cells to pluripotency, and his lab continues to investigate the molecular mechanisms of nuclear reprogramming by oocytes and eggs. We met John in his Cambridge office to discuss his career and hear his thoughts on the past, present and future of reprogramming. Your first paper was published in 1954 and concerned not embryology but entomology. How did that come about? Well, that early paper was published in the Entomologist’s Monthly Magazine. Throughout my early life, I really was interested in insects, and used to collect butterflies and moths. When I was an undergraduate I liked to take time off and go out to Wytham Woods near Oxford to see what I could find. So I went out one cold spring day and there were no butterflies about, nor any moths, but, out of nowhere, there was a fly – I caught it, put it in my bottle, and had a look at it. The first thing that was obvious was that it wasn’t a fly, it was a hymenopteran, but when I tried to identify it I simply could cells in the body have the same genes. -

Network Aesthetics

Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 ABSTRACT Network Aesthetics: American Fictions in the Culture of Interconnection by Patrick Jagoda Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Priscilla Wald, Supervisor __________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy W. Lenoir ___________________________ Frederick C. Moten An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Patrick Jagoda 2010 Abstract Following World War II, the network emerged as both a major material structure and one of the most ubiquitous metaphors of the globalizing world. Over subsequent decades, scientists and social scientists increasingly applied the language of interconnection to such diverse collective forms as computer webs, terrorist networks, economic systems, and disease ecologies. The prehistory of network discourse can be