Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 No. 1, Spring 2015

New Horizons Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part II The Viola Concertos of J. G. Graun and M. H. Graul Unconfused The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Volume 31 Number 1 Number 31 Volume Turn-Out in Standing Journal of the American Viola Society Viola American the of Journal Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2015: Volume 31, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 9 Primrose Memorial Concert 2015 Myrna Layton reports on Atar Arad’s appearance at Brigham Young University as guest artist for the 33rd concert in memory of William Primrose. p. 13 42nd International Viola Congress in Review: Performing for the Future of Music Martha Evans and Lydia Handy share with us their experiences in Portugal, with a congress that focused on new horizons in viola music. Feature Articles p. 19 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II After a fascinating look at Borisovsky’s life in the previous issue, Elena Artamonova delves into the violist’s arrangements and editions, with a particular focus on the Glinka’s viola sonata p. 31 The Viola Concertos of J.G. Graun and M.H. Graul Unconfused The late Marshall ineF examined the viola concertos of J. G. Graul, court cellist for Frederick the Great, in arguing that there may have been misattribution to M. H. Graul. Departments p. 39 With Viola in Hand: A Passion Absolute–The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet The Absolute eroZ Quartet has captured the attention of violists in some 60 countries. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 28 No. 1, Spring 2012

y t e i c o S a l o i V n a c i r e m A e h t Features: 1 f IVC 39 Review r e o b Bernard Zaslav: m From Broadway u l to Babbitt N a Sergey Vasilenko's 8 n Viola Compositions 2 r e m u u l o V o J Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2012 Volume 28 Number 1 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In Memoriam ~ IVC Host Letter Feature Articles p. 13 International Viola Congress XXXIX in Review: Andrew Filmer and John Roxburgh report from Germany p. 19 Bowing for Dollars: From Broadway to Babbitt: Bernard Zaslav highlights his career as Broadway musician, recording artist, and quartet violist p. 33 Unknown Sergey Vasilenko and His Viola Compositions: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives: Elena Artamonova uncovers works by Russian composer Sergey Vasilenko Departments p. 49 In the Studio: Yavet Boyadjiev chats with legendary Thai viola teacher Choochart Pitaksakorn p. 57 Student Life: Meet six young violists featured on NPR’s From the Top p. 65 With Viola in Hand: George Andrix reflects on his viola alta p. 69 Recording Reviews On the Cover: Karoline Leal Viola One Violist Karoline Leal uses her classical music background for inspiration in advertising, graphic design, and printmaking. Viola One is an alu - minum plate lithograph featuring her viola atop the viola part to Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. To view more of her art, please visit: www.karolineart.daportfolio.com. -

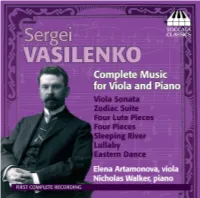

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova

Feature Article Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova Forty-two years after Vadim Borisovsky’s death, the rubato balanced with an immaculate sense for rhythm, recent re-publication of some of his arrangements were never at the expense of the coherence of music he and recordings has generated further interest in the performed, regardless of its period, as his recordings violist. The appeal of his works attests to the depth eloquently attest. and significance of his legacy for violists in the twenty- first century. The first part of this article focused on The discography of Borisovsky as a member of the previously unknown but important biographical facts Beethoven String Quartet is far more extensive, with about Borisovsky’s formation and establishment as a more than 150 works on audio recordings. It comprises viola soloist and his extensive poetic legacy that have music by Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Ravel, only recently come to light. The second part of this Chausson, Berg, Hindemith, and other composers article provides an analysis of Borisovsky’s style of playing of the twentieth century, with a strong emphasis on based on his recordings, concert collaborations, and Russian heritage from Glinka and Rachmaninov to transcription choices and reveals Borisovsky’s special Miaskovsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. This repertoire approach to the enhancement and enrichment of the was undoubtedly influential for Borisovsky in his own viola’s instrumental and timbral possibilities in his selection of transcription choices for the viola. performing editions, in which he closely followed the historical and stylistic background of the composers’ Performing Collaborations manuscripts. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 100, 1980

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundredth Season, 1980-81 PRE-SYMPHONY CHAMBER CONCERTS Thursday, 20 November at 6 Saturday, 22 November at 6 SHEILA FIEKOWSKY, violin NANCY BRACKEN, violin BERNARD KADINOFF, viola ROBERT RIPLEY, cello MICHAEL ZARETSKY, viola TATIANA YAMPOLSKY, piano SHOSTAKOVICH String Quartet No. 7, Opus 108 Allegretto Lento Allegro Mmes. FIEKOWSKY and BRACKEN, Messrs. KADINOFF and RIPLEY SHOSTAKOVICH Viola Sonata, Opus 147 Moderato Allegretto Adagio Mr. ZARETSKY and Ms. YAMPOLSKY made possible by ^S StateStreet Baldwin piano Please exit to your left for supper following the concert. 35 This is a CoacH Belt It is one of eleven models we make out of real Glove Tanned Cowhide in ten colors and eight lengths for men 5 and women from size 26 to 40. Coach Belts are sold in many nice stores throughout the country. If you cannot find the one you want in a store near you, you can also order it directly from the Coach Factory in New York. For Catalogue and Store List write: Consumer Service, Coach Leatherware, 516 West 34th Street, New York City 10001. 36 Dmitri Shostakovich String Quartet No. 7, Opus 108 Shostakovich wrote the seventh of his fifteen string quartets in 1960, a memorial tribute to his first wife, Nina Vasilyevna. Like so much of the chamber music of his last years, this quartet is imbued with an inwardness, a sense of personal expression that is not always present in the sometimes bombastic public statements that were his symphonies. -

Download Booklet

572318bk Prokofiev:570034bk Hasse 22/5/11 9:33 PM Page 4 Matthew Jones Matthew is violist of the Bridge Duo (with pianist Michael Hampton) and the Debussy Ensemble. Recent recital and chamber music venues include the Wigmore Hall, London’s South Bank and the Forbidden City Concert Hall in Beijing; he made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in 2008. He was also a member of the Badke String Quartet when they won the 2007 Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition, and performs regularly with Ensemble MidtVest in Denmark. He is greatly in demand as a concerto soloist, festival artist and contemporary music performer. Matthew is a professor at Trinity College of Music, Royal Welsh College and Charterhouse International Music Festival, PROKOFIEV and has given masterclasses in the USA, Australia, Malaysia, Japan and throughout Europe. His extensive discography includes two Bridge Duo recordings of English music, Hilary Tann’s chamber music and Haflidi Hallgrimsson’s chamber works. Born in Swansea, Wales, Matthew is also a composer, conductor, mathematics graduate and Suite from teacher of the Alexander Technique and Kundalini Yoga. For more information, visit www.matt-jones.com. Rivka Golani Romeo and Rivka Golani is recognized as one of the great violists and musicians of modern times. BBC Music Magazine included her in its list of the 200 most important instrumentalists and the five most important violists currently performing. Her contributions to the Juliet advancement of viola technique have already given her a place in the history of the instrument and have been a source of inspiration not only to other players but to many composers who have been motivated by her mastery: more than 215 works have been (arr. -

Ideazione E Coordinamento Della Programmazione a Cura Di Massimo Di Pinto Con La Collaborazione Di Leonardo Gragnoli

Ideazione e coordinamento della programmazione a cura di Massimo Di Pinto con la collaborazione di Leonardo Gragnoli gli orari indicati possono variare nell'ambito di 4 minuti per eccesso o difetto Venerdì 29 luglio 2016 00:00 - 02:00 euroclassic notturno martinu, bohuslav (1890-1959) sonatina per cl e pf moderato, allegro - andante - poco allegro. valentin uriupin, cl; yelena komissarova, pf durata: 11.23 CR redio ceka bartók, béla (1881-1945) danze popolari rumene (SZ 68) orchestraz. dell'autore dall'orig per pf (SZ 56). danza del bastone (energico e festoso) - danza della fascia (allegro) - danza sul posto (andante) - danza del corno (moderato) - polka rumena (allegro) - danza veloce (allegro) - danza veloce (più allegro). BBC national orch of wales dir. james clark (reg. cardiff, 31/01/2001) durata: 6.42 BBC british broadcasting corporation prokofiev, sergei (1891-1953) romeo e giulietta: danza dei cavalieri arrang. per vla e pf di vadim borisovsky gyözö máté, vla; balázs szokolay, pf durata: 5.36 MR radiotelevisione ungherese gluck, christoph willibald (1714-1787) paride ed elena: danze dall'opera allegro con spirito - ciaccona (moderato con grazia) - gavotte. radio bratislava symphony orch dir. ludovít rajter durata: 12.01 SR radio slovacca telemann, georg philipp (1681-1767) trio per fl traverso vla da gamba e b. c. n. 6 da "essercizii musici" camerata köln: karl kaiser, fl traverso; rainer zipperling e ghislaine wauters, vla da gamba; yasunori imamura, tiorba; sabine bauer, org durata: 7.36 WDR radio della germania occidentale lasso, orlando di (1532-1594) tre composizioni vocali jubilate deo, mottetto - io ti voria contar la pena mia, villanella alla napoletana - tristis est anima mea, mottetto. -

ERIKA ECKERT, Viola

ERIKA ECKERT, viola University of Colorado Boulder College of Music Boulder, CO 80309 [email protected] EDUCATION Eastman School of Music – Rochester, NY -- Bachelor of Music – 1987 Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music – Cincinnati, OH – 1984 - 1985 Ohio State University – Columbus, OH – 1982 - 1984 FACULTY APPOINTMENTS 1994 - Present University of Colorado at Boulder Boulder, CO Assistant Professor of Viola – 1994 - 2002 Associate Professor of Viola – 2002 - present Chair of Strings – 2014 - present Duties include teaching applied viola majors at the undergraduate, masters and doctoral level, coaching and assist in coordinating chamber music, and some years, co-teaching Orchestral Repertoire. Chairing Strings encompasses the usual administrative responsibilities. 2011 – Present Brevard Music Center Brevard, NC Viola Instruction and Chamber Music Coaching Duties include teaching eight talented high school, undergraduate and graduate viola students, coaching string quartets, and playing, side-by-side the students, in the Brevard Music Center Orchestra. 1994 – 1996 Chautauqua Institution Chautauqua, NY Chamber Music Coordinator and Viola Instructor For three summers, coordinated the chamber music program for the Music Festival Symphony Orchestra, a college-level orchestra of approximately one hundred members. Proctored the chamber music auditions at the beginning of the summer and put ensembles together for two three-week sessions, coordinated coaching assignments, master classes and performances, and maintained a full studio of viola students and chamber music groups. 1993 – 1994 Baldwin Wallace College-Conservatory of Music Berea, OH Viola Instruction and Chamber Music Coaching Duties included teaching undergraduate viola majors and non-majors and coaching chamber music. 1988 – 1994 Cleveland Institute of Music Cleveland, OH Viola Instruction and Chamber Music Coaching As a member of the Cavani String Quartet, coordinated the chamber music program, including the Intensive Quartet Seminar and the Apprenticeship Quartet Program. -

Of New Collected Works

DSCH PUBLISHERS CATALOGUE of New Collected Works FOR HIRE For information on purchasing our publications and hiring material, please apply to DSCH Publishers, 8, bld. 5, Olsufievsky pereulok, Moscow, 119021, Russia. Phone: 7 (499) 255-3265, 7 (499) 766-4199 E-mail: [email protected] www.shostakovich.ru © DSCH Publishers, Moscow, 2019 CONTENTS CATALOGUE OF PUBLICATIONS . 5 New Collected Works of Dmitri Shostakovich .................6 Series I. Symphonies ...............................6 Series II. Orchestral Compositions .....................8 Series III. Instrumental Concertos .....................10 Series IV. Compositions for the Stage ..................11 Series V. Suites from Operas and Ballets ...............12 Series VI. Compositions for Choir and Orchestra (with or without soloists) ....................13 Series VII. Choral Compositions .......................14 Series VIII. Compositions for Solo Voice(s) and Orchestra ...15 Series IX. Chamber Compositions for Voice and Songs ....15 Series X. Chamber Instrumental Ensembles ............17 Series XI. Instrumental Sonatas . 18 Series ХII. Piano Compositions ........................18 Series ХIII. Incidental Music ...........................19 Series XIV. Film Music ...............................20 Series XV. Orchestrations of Works by Other Composers ...22 Publications ............................................24 Dmitri Shostakovich’s Archive Series .....................27 Books ..............................................27 FOR HIRE ..............................................30 -

Proquest Dissertations

M u Ottawa L'Unh-wsiie eanadienne Canada's university FACULTE DES ETUDES SUPERIEURES IfisSJ FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND ET POSTOCTORALES U Ottawa POSDOCTORAL STUDIES L'Universite canadienne Canada's university Jada Watson AUTEUR DE LA THESE /AUTHOR OF THESIS M.A. (Musicology) GRADE/DEGREE Department of Music lATJULfEJ^LTbliP^ Aspects of the "Jewish" Folk Idiom in Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 4, OP.83 (1949) TITREDE LA THESE/TITLE OF THESIS Phillip Murray Dineen _________________^ Douglas Clayton _______________ __^ EXAMINATEURS (EXAMINATRICES) DE LA THESE / THESIS EXAMINERS Lori Burns Roxane Prevost Gary W, Slater Le Doyen de la Faculte des etudes superieures et postdoctorales / Dean of the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies ASPECTS OF THE "JEWISH" FOLK IDIOM IN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH'S STRING QUARTET NO. 4, OP. 83 (1949) BY JADA WATSON Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master's of Arts degree in Musicology Department of Music Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Jada Watson, Ottawa, Canada, 2008 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-48520-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant -

Kevin Lin, Viola Graduate Recital Beilin Han, Piano

Thursday, November 10, 2016 • 7:00 p.m Kevin Lin Graduate Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Thursday, November 10, 2016 • 7:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Kevin Lin, viola Graduate Recital Beilin Han, piano PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827); ed. & arr. William Primrose Notturno for Viola and Piano, Op. 42 (1796-1797, 1803) Marcia: Allegro Adagio Menuetto and Trio: Allegretto Adagio - Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegretto alla Polacca Theme and Variations: Andante quasi Allegretto Marcia: Allegro Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 147 (1975) Moderato Allegretto Adagio Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1953); arr. Vadim Borisovsky Selected pieces from the ballet Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64 (1935) I. Introduction III. Juliet the Young Girl V. Dance of the Knights Kevin Lin is from the studio of Rami Solomonow. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Master of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Kevin Lin • November 10, 2016 PROGRAM NOTES Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827); ed. & arr. William Primrose Notturno for Viola and Piano, Op. 42 (1796-1797, 1803) Duration: 23 minutes The Notturno for Viola and Piano was originally composed by Beethoven as the Serenade for Violin, Viola, and Cello, Op. 8. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, there was growing demand by amateur musicians for arrangements of works that would otherwise require larger number of instrumentalists to perform, and music publishers were more than happy to oblige the demands of the public. -

Disdamusica Cp 2020 Programm.Pdf

5. Engadiner Kammermusiktage 29.08-13.09.2020 29.08.2020, 16:30 Uhr, Gemeindesaal Samedan Trio Aventia 1. Ludwig van Beethoven: Trio op. 11 B-Dur “Gassenhauer” Allegro con brio; Adagio; Tema con variazioni 2. Robert Muczynski: „Fantasy“ Trio op. 26 Allegro energico; Andante con espressione; Allegro deciso 3. Alexander von Zemlinsky: Trio op. 3 d-Moll Allegro ma non troppo; Andante; Allegro 05.09.2020, 16:30 Uhr, Chesa Planta Musiktage zu Gast im historischen Gemeindesaal Samedan Kammermusik aus 4 Jahrhunderten mit 9 Solisten 1. Antonín Dvořák: Quintett für Streichquartett und Klavier op. 81 Allegro, ma non tanto; Dumka 2. Camille Saint-Saens: Dance Macabre „Totentanz“ op. 40 3. Elias Parish Alvar: Introduction, Cadenza und Rondo op. 57 4. Eugène Bozza: Image pour flute seule op. 38 5. Astor Piazzolla: Le Grand Tango 6. Jean Cras: Quintett für Harfe, Flöte, und Streichtrio Assez animé; Animé 7. Johannes Brahms: Klarinettensonate Nr. 2 Es-Dur op. 120 Andante con moto 8. Franz Strauss: Nocturno op. 7 9. Sergei Sergejewitsch Prokofjew: 3 Stücke aus dem Ballet Romeo und Julia für Viola und Klavier, Bearbeitung von Vadim Borisovsky, Introduction, Julia, Tanz der Ritter 10. Ernő Dohnányi: Sextett C-Dur op. 37. Allegro appassionata Die Engadiner Kammermusiktage unter dem Patronat der Freunde der Chesa Planta und der Zürcher Hochschule der Künste ZHdK werden ermöglicht durch die G. und H. Kuck - Stiftung für Musik und Kultur. 06.09.2020, 10:30 Uhr, Chesa Planta Musiktage zu Gast im historischen Gemeindesaal Samedan Kammermusik-Matinée: Musik aus 4 Jahrhunderten mit 9 Solisten 1. Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonate für Horn und Klavier F-Dur op.