Swiss Chamber Soloists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 31 No. 1, Spring 2015

New Horizons Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements, Part II The Viola Concertos of J. G. Graun and M. H. Graul Unconfused The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet Volume 31 Number 1 Number 31 Volume Turn-Out in Standing Journal of the American Viola Society Viola American the of Journal Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2015: Volume 31, Number 1 p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President News & Notes p. 9 Primrose Memorial Concert 2015 Myrna Layton reports on Atar Arad’s appearance at Brigham Young University as guest artist for the 33rd concert in memory of William Primrose. p. 13 42nd International Viola Congress in Review: Performing for the Future of Music Martha Evans and Lydia Handy share with us their experiences in Portugal, with a congress that focused on new horizons in viola music. Feature Articles p. 19 Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II After a fascinating look at Borisovsky’s life in the previous issue, Elena Artamonova delves into the violist’s arrangements and editions, with a particular focus on the Glinka’s viola sonata p. 31 The Viola Concertos of J.G. Graun and M.H. Graul Unconfused The late Marshall ineF examined the viola concertos of J. G. Graul, court cellist for Frederick the Great, in arguing that there may have been misattribution to M. H. Graul. Departments p. 39 With Viola in Hand: A Passion Absolute–The Absolute Zero Viola Quartet The Absolute eroZ Quartet has captured the attention of violists in some 60 countries. -

Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 9-25-2006 Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III Susan Waterbury Debra Moree Elizabeth Simkin Jennifer Hayghe Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Waterbury, Susan; Moree, Debra; Simkin, Elizabeth; and Hayghe, Jennifer, "Faculty Recital: Mozart/Shostakovich III" (2006). All Concert & Recital Programs. 5058. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/5058 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. ITHACA COLLEGE SCHOOL OF MUSIC FACULTY RECITAL MOZART/SHOSTAKOVICH III An evening of chamber music celebrating the 250th birth anniversary of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) and the 100th birth anniversary of Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Susan Waterbury, violin Debra Moree, viola Elizabeth Simkin, cello Jennifer Hayghe, piano Hockett Family Recital Hall Monday, September 25, 2006 7:00 p.m. ITHACA I PROGRAM Piano Sonata No. 18 in D Major, Wolfgang Amadeus :Mozart K576 (1789) (1756-1791) Allegro Adagio Allegretto Sonata for Viola & Piano, Op. 147 (1975) Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Moderato Allegretto Adagio INTERMISSION Trio for Violin, Cello & Piano, Dmitri Shostakovich No. 2 in e minor, Op. 67 (1944) Andante Allegro non troppo Largo Allegretto Program Notes Mozart and Shostakovitch III The pairing of Mozart and Shostakovich, born 150 years apart, is more natural than e might initially suspect. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (27 January 1756- 5 cember 1791), the seventh and last child born to Leopold Mozart and his wife Maria Anna, is the most famous musical prodigy in history. -

Numerical Listing

SEQ DISC NO LABEL CDN PRICE PERFORMER DESCRIPTION a a THREE FOR TWO! ON ALL ITEMS PRICED AT £5.00, ONE- THIRD (1/3) OFF ALL ORDERS FOR 3 OR MORE a a 23776 0 10 1441-3 Supraphon, blue m A1 £10.00 Talich, Vaclav Vol. 1. Suk: Serenade for Strings; Asrael; Ripening. Czech PO c 22047 1 11 1106 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Vlach SQ Beethoven: Quartets, Opp.18-1; 18-6 bb 22524 1 11 1755 Supraphon s A1 £5.00 Prague SQ Lubomir Zelezny: Clt. Quintet; Wind Quintet; Piano Trio. Prague Wind Quintet, Smetana Trio bb 23786 10 Penzance, USA m A1 £8.00 Callas, Maria, s Wagner: Parsifal, Act 2. Baldelli, Modesti, Pagliughi, -Gui. Live, 20.xi.50. In Italian a 22789 1007831 VdsM, References m A1 £7.00 Kreisler, Fritz, vn Beethoven; Sonatas 5, "Spring"; 9, "Kreutzer". F. Rupp, pf bb 23610 101 Rara Avis, lacquer m A-1- £10.00 Ginsburg, Grigory, pf Liszt: Bells of Geneva, Campanella, Rigoletto, Spanish Rhapsody / Weber: Rondo brillante / Chopin: Etudes, Op.25, 1-3. From 78s, semi-private issue b 22800 12T 160 Topic m A1 £7.00 Folk Songs of Britain, 1 Child Ballads 1. Various artists (field recordings) e 22707 13029 AP DGG, Archiv, Ger., m A1 £40.00 Schneiderhan, Wolfgang, vn Bach: Partita 2, D minor, for solo violin. Sleeve: buff, gatefold 10" bb 22928 133 004 SLPE DGG, Ger., tulip, 10" s A1 £12.00 Bolechowska, Alina, s Chopin: Lieder. S. Nadgrizowski, pf a 22724 133 122 SLP DGG, Ger., red, tulip, s A1 £12.00 Markevitch, Igor, dir Mozart: Coronation Mass. -

The Soviet Experience Volume Iv Also with the Pacifica Quartet on Cedille Records String Quartets by Shostakovich: Quartets Nos

THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME IV ALSO WITH THE PACIFICA QUARTET ON CEDILLE RECORDS STRING QUARTETS BY SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 13-15 THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL III DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH CDR 90000 138 SCHNITTKE: QUARTET No. 3 “This Shostakovich cycle is turning out to be one of the AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES most riveting of recent years. Pacifica’s Shostakovich cycle already is shaping up as definitive.” —BBC Music Magazine THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME II STRING QUARTETS BY THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL II DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 1-- 4 CDR 90000 130 PROKOFIEV: QUARTET NO. 2 “Having reached the halfway point, the Pacifica’s Shostakovich cycle already is shaping up as definitive, even in a field stocked with . formidable Russian contenders.” PACIFICA QUARTET —The Classical Review SovietExpVol2_Mech.indd 1 12/9/11 10:41 AM THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOL I CDR 90000 127 “The excellent Pacifica Quartet . offers electrifying interpretations . The group conveys every shade of Shostakovich’s extreme emotional palette.” —The New York Times MENDELSSOHN: THE COMPLETE STRING QUARTETS CDR 90000 082 “This box sets a new gold standard for performances of Mendelssohn’s string quartets.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch PACIFICA QUARTET SovietExpVol4_MECH.indd 1 10/2/2013 2:58:04 PM Producer & Engineer Judith Sherman THE SOVIET EXPERIENCE VOLUME IV PACIFICA QUARTET Assistant Engineer & Digital Editing Bill Maylone Shostakovich Quartet No. 14 and (most of) 15 Editing James Ginsburg STRING QUARTETS BY SHOSTAKOVICH: QUARTETS NOS. 13-15 Editing Assistance Jeanne Velonis DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH SCHNITTKE: QUARTET NO. 3 Recorded Shostakovich Quartets Nos. 13 and 14: December 16–18, 2012; Shostakovich Quartet No. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 28 No. 1, Spring 2012

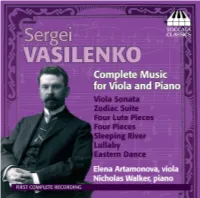

y t e i c o S a l o i V n a c i r e m A e h t Features: 1 f IVC 39 Review r e o b Bernard Zaslav: m From Broadway u l to Babbitt N a Sergey Vasilenko's 8 n Viola Compositions 2 r e m u u l o V o J Journal of the American Viola Society A publication of the American Viola Society Spring 2012 Volume 28 Number 1 Contents p. 3 From the Editor p. 5 From the President p. 7 News & Notes: Announcements ~ In Memoriam ~ IVC Host Letter Feature Articles p. 13 International Viola Congress XXXIX in Review: Andrew Filmer and John Roxburgh report from Germany p. 19 Bowing for Dollars: From Broadway to Babbitt: Bernard Zaslav highlights his career as Broadway musician, recording artist, and quartet violist p. 33 Unknown Sergey Vasilenko and His Viola Compositions: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives: Elena Artamonova uncovers works by Russian composer Sergey Vasilenko Departments p. 49 In the Studio: Yavet Boyadjiev chats with legendary Thai viola teacher Choochart Pitaksakorn p. 57 Student Life: Meet six young violists featured on NPR’s From the Top p. 65 With Viola in Hand: George Andrix reflects on his viola alta p. 69 Recording Reviews On the Cover: Karoline Leal Viola One Violist Karoline Leal uses her classical music background for inspiration in advertising, graphic design, and printmaking. Viola One is an alu - minum plate lithograph featuring her viola atop the viola part to Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony. To view more of her art, please visit: www.karolineart.daportfolio.com. -

Toccata Classics TOCC 0127 Notes

SERGEI VASILENKO AND THE VIOLA by Elena Artamonova The viola is occasionally referred to as ‘the Cinderella of instruments’ – and, indeed, it used to take a fairy godmother of a player to allow this particular Cinderella to go to the ball; the example usually cited in the liberation of the viola in a solo role is the British violist Lionel Tertis. Another musician to pay the instrument a similar honour – as a composer rather than a player – was the Russian Sergei Vasilenko (1872–1956), all of whose known compositions for viola, published and unpublished, are to be heard on this CD, the fruit of my investigations in libraries and archives in Moscow and London. None is well known; some are not even included in any of the published catalogues of Vasilenko’s music. Only the Sonata was recorded previously, first in the 1960s by Georgy Bezrukov, viola, and Anatoly Spivak, piano,1 and again in 2007 by Igor Fedotov, viola, and Leonid Vechkhayzer, piano;2 the other compositions receive their first recordings here. Sergei Nikiforovich Vasilenko had a long and distinguished career as composer, conductor and pedagogue in the first half of the twentieth century. He was born in Moscow on 30 March 1872 into an aristocratic family, whose inner circle of friends consisted of the leading writers and artists of the time, but his interest in music was rather capricious in his early childhood: he started to play piano from the age of six only to give it up a year later, although he eventually resumed his lessons. In his mid-teens, after two years of tuition on the clarinet, he likewise gave it up in favour of the oboe. -

Dissertation First Pages

Dissertation in Music Performance by Joachim C. Angster A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2020 Dissertation Committee: Assistant Professor Caroline Coade, Co-Chair Professor David Halen, Co-Chair Professor Colleen Conway Associate Professor Max Dimoff Professor Daniel Herwitz Joachim C. Angster [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2563-2819 © Joachim C. Angster 2020 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to members of my Doctoral Committee and to my teacher Professor Caroline Coade in particular, for making me a better musician. I also would like to give special thanks to my collaborators Arianna Dotto, Meridian Prall, Ji-Hyang Gwak, Taylor Flowers, and Nathaniel Pierce. Finally, I am grateful for the continuous support of my parents, and for the invaluable help of Anna Herklotz and Gabriele Dotto. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT iv FIRST DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 1 Program Notes 2 SECOND DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 18 Program Notes 19 THIRD DISSERTATION RECITAL: Program 27 Program Notes 28 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 iii ABSTRACT This dissertation pertains to three viola recitals, which were respectively performed on 2 October 2019, 20 January 2020, and 9 March 2020. Each recital program embraced a specific theme involving little-performed works as well as staples from the viola repertoire, and covered a wide range of different musical styles. The first recital, performed with violinist Arianna Dotto, focused on violin and viola duo repertoire. Two pieces in the Classical and early Romantic styles by W. A. Mozart and L. -

Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova

Feature Article Vadim Borisovsky and His Viola Arrangements: Recent Discoveries in Russian Archives and Libraries, Part II Elena Artamonova Forty-two years after Vadim Borisovsky’s death, the rubato balanced with an immaculate sense for rhythm, recent re-publication of some of his arrangements were never at the expense of the coherence of music he and recordings has generated further interest in the performed, regardless of its period, as his recordings violist. The appeal of his works attests to the depth eloquently attest. and significance of his legacy for violists in the twenty- first century. The first part of this article focused on The discography of Borisovsky as a member of the previously unknown but important biographical facts Beethoven String Quartet is far more extensive, with about Borisovsky’s formation and establishment as a more than 150 works on audio recordings. It comprises viola soloist and his extensive poetic legacy that have music by Beethoven, Haydn, Mozart, Schubert, Ravel, only recently come to light. The second part of this Chausson, Berg, Hindemith, and other composers article provides an analysis of Borisovsky’s style of playing of the twentieth century, with a strong emphasis on based on his recordings, concert collaborations, and Russian heritage from Glinka and Rachmaninov to transcription choices and reveals Borisovsky’s special Miaskovsky, Prokofiev, and Shostakovich. This repertoire approach to the enhancement and enrichment of the was undoubtedly influential for Borisovsky in his own viola’s instrumental and timbral possibilities in his selection of transcription choices for the viola. performing editions, in which he closely followed the historical and stylistic background of the composers’ Performing Collaborations manuscripts. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 100, 1980

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Sir Colin Davis, Principal Guest Conductor Joseph Silverstein, Assistant Conductor One Hundredth Season, 1980-81 PRE-SYMPHONY CHAMBER CONCERTS Thursday, 20 November at 6 Saturday, 22 November at 6 SHEILA FIEKOWSKY, violin NANCY BRACKEN, violin BERNARD KADINOFF, viola ROBERT RIPLEY, cello MICHAEL ZARETSKY, viola TATIANA YAMPOLSKY, piano SHOSTAKOVICH String Quartet No. 7, Opus 108 Allegretto Lento Allegro Mmes. FIEKOWSKY and BRACKEN, Messrs. KADINOFF and RIPLEY SHOSTAKOVICH Viola Sonata, Opus 147 Moderato Allegretto Adagio Mr. ZARETSKY and Ms. YAMPOLSKY made possible by ^S StateStreet Baldwin piano Please exit to your left for supper following the concert. 35 This is a CoacH Belt It is one of eleven models we make out of real Glove Tanned Cowhide in ten colors and eight lengths for men 5 and women from size 26 to 40. Coach Belts are sold in many nice stores throughout the country. If you cannot find the one you want in a store near you, you can also order it directly from the Coach Factory in New York. For Catalogue and Store List write: Consumer Service, Coach Leatherware, 516 West 34th Street, New York City 10001. 36 Dmitri Shostakovich String Quartet No. 7, Opus 108 Shostakovich wrote the seventh of his fifteen string quartets in 1960, a memorial tribute to his first wife, Nina Vasilyevna. Like so much of the chamber music of his last years, this quartet is imbued with an inwardness, a sense of personal expression that is not always present in the sometimes bombastic public statements that were his symphonies. -

Pragadigitals English 03-2018

catalogue Praga Digitals PRAGA DIGITALS CATALOGUE 03-2018 http://www.pragadigitals.com ISAAC ALBENIZ (1860-1909) CD1 : IBERIA, 12 “Impressions”, for piano (1905-1908) / Book I, dedicated to Madame Ernest Chausson (1906) /Book II, dedicated to Blanche Selva (1906) / Book III, dedicated to Marguerite Hasselmans (1907) / Book IV, dedicated to Madame Pierre Lalo (1908) PRD/DSD 350 075 CD2 : IBERIA Suite (transcriptions for orchestra by E.Fernández Arbós, 1909-1927) / CANTOS DE ESPAÑA, Op.232, for piano / ESPAÑA, “Souvenirs” for piano (1897) / MALLORCA, barcarola Op.202 (1891) / RECUERDOS DE VIAJE, Op.71 (1887) 3,149,028,025,927 SACD Alicia de LARROCHA, p (CD1) - Orchestre du Théâtre National de l’Opéra de Paris, Manuel ROSENTHAL - Jean-Joël BARBIER, p JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685-1750) PRD 250 103 SONATAS BWV 1020,1022,1027-1029, WRITTEN FOR HARPSICHORD & VIOLA 794,881,396,023 Zuzana Řů žicková (harpsichord), Josef Suk (viola) Mily BALAKIREV (1837-1910) Russian Symphonies (I) : PRD 250 363 SYMPHONY No.1 in C major (1866-99) SYMPHONY No.2 in D minor (1900-8) 3,149,028,102,024 Genuine Stereo The Philharmonia, London - Herbert von KARAJAN - Moscow Radio Symphony Gennadi ROZHDESTVENSKY BÉLA BARTÓK (1881-1945) PRD 250 135 VIOLIN SONATAS No 1 Sz.75 (1921) & No. 2 Sz.76 794,881,602,124 Peter Csaba (violin), Jean-François Heisser (piano) SONATAS FOR TWO PIANOS AND PERCUSSION Sz. 110. THE MIRACULOUS MANDARIN (written by Bartok for two pianos) . TWO PRD/DSD 250 184 PICTURES (written by Z.Kocsis for two pianos) 794,881,680,924 SACD Jean-François Heisser, Marie-Josèphe Jude (pianos), Florent Jodelet, Michel Cerutti (percussions) RHAPSODY Nos 1, 2 FOR VIOLIN and PIANO Sz.86 & Sz 89 (first release of the original Friss ), HUNGARIAN FOLK SONGS (26) (from PRD/DSD 250 190 FOR THE CHILDREN), RUMANIAN FOLK DANCES, SONATINA Sz 56 794,881,681,525 SACD Peter Csaba (violin), Peter Frankl (piano) STRING QUARTET No 1 SZ 40 PRD/DSD 250 235 STRING QUARTET No 2 SZ 67 794,881,822,423 SACD Parkanyi Quartet Page 1 de 58 catalogue Praga Digitals STRING QUARTET No. -

Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-Musical References in Shostakovich’S Viola Sonata

Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-musical References in Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata By John David Roxburgh Exegesis Submitted to Massey University and Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Musical Arts In Performance New Zealand School of Music 2013 i Abstract Approaches to the Performance of Musical and Extra-musical References in Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata by John David Roxburgh Supervisor: Professor Donald Maurice Secondary Supervisor: Dr David Cosper This paper is an examination of Shostakovich’s Viola Sonata, op. 147, for developing a stylistically informed performance practice. It is divided into three parts: The first is an investigation of symbolism present within the work itself; the second a comparative analysis of recordings; and the third a discussion of how the author uses these approaches to make performance decisions. The first aspect looks to the score itself to identify quotations of and allusions to other works, and considers the reasoning for this. The second analyses string choice and tempo of recordings to consider how these might reflect symbolic considerations. The third part discusses specific performance decisions, and the reasons on which they are based. ii Table of Contents Title Page i Abstract ii Table of Contents iii List of Recording Examples iv Introduction 1 Part I: Investigation of Musical and Extra-Musical References 4 Part II: Comparative Analysis of Recordings 23 Part III: Discussion of Performance Decisions 36 Conclusion 39 Bibliography 42 Appendix I: String Choice Analysis 45 Appendix II: Tempo Analysis 91 iii List of Recording Examples (on audio CD attached) Track No. -

Download Booklet

572318bk Prokofiev:570034bk Hasse 22/5/11 9:33 PM Page 4 Matthew Jones Matthew is violist of the Bridge Duo (with pianist Michael Hampton) and the Debussy Ensemble. Recent recital and chamber music venues include the Wigmore Hall, London’s South Bank and the Forbidden City Concert Hall in Beijing; he made his Carnegie Hall recital debut in 2008. He was also a member of the Badke String Quartet when they won the 2007 Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition, and performs regularly with Ensemble MidtVest in Denmark. He is greatly in demand as a concerto soloist, festival artist and contemporary music performer. Matthew is a professor at Trinity College of Music, Royal Welsh College and Charterhouse International Music Festival, PROKOFIEV and has given masterclasses in the USA, Australia, Malaysia, Japan and throughout Europe. His extensive discography includes two Bridge Duo recordings of English music, Hilary Tann’s chamber music and Haflidi Hallgrimsson’s chamber works. Born in Swansea, Wales, Matthew is also a composer, conductor, mathematics graduate and Suite from teacher of the Alexander Technique and Kundalini Yoga. For more information, visit www.matt-jones.com. Rivka Golani Romeo and Rivka Golani is recognized as one of the great violists and musicians of modern times. BBC Music Magazine included her in its list of the 200 most important instrumentalists and the five most important violists currently performing. Her contributions to the Juliet advancement of viola technique have already given her a place in the history of the instrument and have been a source of inspiration not only to other players but to many composers who have been motivated by her mastery: more than 215 works have been (arr.