The Rise and Fall of Vaporwave: Resistance and Sublimation in On-Line Counter- Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Troy High School Vol

FEBRUARY 16, 2018ORACLETROY HIGH SCHOOL VOL. 53, ISSUE 7 2200 E. DOROTHY LANE, FULLERTON, CA 92831 What is Bitcoin and cryptocurrency? Cryptocurrency is a transferable, digital currency which operates independently of a central bank. Users can ex- change virtual money in peer-to-peer transactions while “miners,” people who run the software, encrypt data to protect users’ money. By doing so, they create more bit- coins which can then affect the overall value of bitcoins. The more bitcoins sold, the more their value decreases. cryptocurrency transactions By Faith-Carmen Le develop blockchains. Addition- of Feb. 8, one bitcoin was worth STAFF WRITER ally, millions of users send their $7744.27, exemplifying the Photo by Ashley Branson private information across the dramatic fluctuations in crypto- PHOTO world using different servers currency cost. Warriors should which can potentially threaten avoid wrongly treating Bitcoin their personal security. as a joke since real money can We’ve all heard about it. Cryptocurrency is relatively be lost by investing in bitcoins. How six years ago one bitcoin new, and it may feel exciting to Moreover, because crypto- was worth less than a Big currency can be used to Person A and Person B want to perform a bitcoin transaction Mac, but is now worth buy and sell almost any- thousands today. Bitcoin is “The world of thing, the world of crypto- currently the most popular cryptocurrency opens up a new currency opens up a new form of cryptocurrency. avenue for criminals to In fact, many tech-savvy avenue for criminals to exploit. exploit. Bitcoin can poten- Warriors own bitcoins and Any item from cars to concert tially increase crime be- use cryptocurrency be- tickets to drugs is fair game for cause illegal transactions cause it does not require a bitcoin transaction.” become easier to complete Cryptographic keys are assigned to the transaction that investors to go through and harder to track. -

Exploring Queer Expressions in Mens Underwear Through Post Internet Aesthetic As Vaporwave

Mens underwear :Exploring queer expressions in mens underwear through post internet aesthetic as Vaporwave. Master in fashion design Mario Eurenius 2018.6.09. 1. Abstract This work explores norms of dress design by the use of post internet aesthetics in mens underwear. The exploration of underwear is based on methods formed to create a wider concept of how mens underwear could look like regarding shape, color, material and details. Explorations of stereotypical and significant elements of underwear such as graphics and logotypes has been reworked to create a graphical identity bound to a brand. This is made to contextualize the work aiming to present new options and variety in mens underwear rather than stating examples using symbols or stereotypic elements. In the making of the examples for this work the process goes front and back from digital to physical using different media to create compositions of color, graphic designs and outlines using transfer printer, digital print, and laser cutting machine. Key words: Mens underwear, graphic, colour, norm, identity, post internet, laser cut. P: P: 2 Introduction to the field 3 Method 15 What is underwear? 39 Shape, Rough draping Historical perspective 17 Male underwear and nudity 41 From un-dressed to dressed 18 Graphics in fashion and textiles 42 Illustrator sketching 19 Differencesin type and categories of mensunderwear 43 shape grapich design 2,1 Background 3.1 Developement 45 collection of pictures 49 Colour 20 Vaporwave 50 Rough draping Japanese culture 21 Mucis 55 Rough draping 2 22 -

RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY and MEMORY in HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF FILM AND MEDIA ARTS (2019) Vol. 4, Nº. 2 pp. 24-37 © 2019 BY-NC-ND ijfma.ulusofona.pt DOI: 10.24140/ijfma.v4.n2.02 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MATERIALITY AND MEMORY IN HAUNTOLOGICAL APPROPRIATION Abstract This research examines the spectrality of an- MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD imation and other media based on the photo- graphic trace. Using diverse examples from pop- ular culture and the author’s own investigative practice in media art, this paper looks at how ar- chival media is re-used and can be brought back to life in new moving image works, in a gesture we might call hauntological appropriation. While sampling and re-using old materials is nothing new, over the last 15 years we have seen an ongoing tendency to foreground the ghostly qualities of vintage recordings and found foot- age, and a recurrent fetishisation and simula- tion of obsolete technologies. Here we examine the philosophies and productions behind this hauntological turn and why the materiality of still and moving image media has become such a focus. We ask how that materiality effects the machines that remember for us, and how we re- use these analogue memories in digital cultures. Due to the multimodal nature of the author’s creative practice, photography, video art, doc- umentary film and animation, are interrogated here theoretically. Re-animating the ghosts of old media can reveal ontological differences between these forms, and a ghostly synergy be- tween the animated and the photographic. Keywords: hauntology, animation, memory, media * University of Leeds, United Kingdom archaeology, appropriation, ontology, animated [email protected] documentary 24 RE-ANIMATING GHOSTS MICHAEL PETER SCHOFIELD Every culture has its phantoms and the spectral- how we can foreground their specific materiality, and the ity that is conditioned by its technology (Derrida, haunting associations with personal and cultural memory Amelunxen, Wetzel, Richter, & Fort, 2010, p. -

Metamodernism and Vaporwave: a Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture

Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology Volume 14 | Issue 1 Article 3 Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Nicholas Morrissey University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Recommended Citation Morrissey, Nicholas. “Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture.” Nota Bene: Canadian Undergraduate Journal of Musicology 14, no. 1 (2021): 64-82. https://doi.org/10.5206/notabene.v14i1.13361. Metamodernism and Vaporwave: A Study of Web 2.0 Aesthetic Culture Abstract With the advent of Web 2.0, new forms of cultural and aesthetic texts, including memes and user generated content (UGC), have become increasingly popular worldwide as streaming and social media services have become more ubiquitous. In order to acknowledge the relevance and importance of these texts in academia and art, this paper conducts a three-part analysis of Vaporwave—a unique multimedia style that originated within Web 2.0—through the lens of a new cultural philosophy known as metamodernism. Relying upon a breadth of cultural theory and first-hand observations, this paper questions the extent to which Vaporwave is interested in metamodernist constructs and asks whether or not the genre can be classed as a metamodernist text, noting the dichotomy and extrapolation of nostalgia promoted by the genre and the unique instrumentality it offers to its consumers both visually and sonically. This paper ultimately theorizes that online culture will continue to play an important role in cultural production, aesthetic mediation, and even -

The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks As Source Identifiers for Expressive Works*

YAQUINTO.TOPRINTER (DO NOT DELETE) 2/8/2017 11:25 AM The Social Significance of Modern Trademarks: Authorizing the Appropriation of Marks as Source Identifiers for * Expressive Works Dieuson Octave is a nineteen-year-old rapper from Florida that recently signed a deal with Atlantic Records. His YouTube videos have millions of views. He releases his music under the name Kodak Black. Some graffiti writers use stickers in addition to spray paint. In San Francisco, a writer named Ther had stickers appropriating the The North Face logo. Instead of reading The North Face in stacked type, Ther’s stickers read “Ther Norco Face.” Norco is a brand of prescription painkiller. Vaporwave is an obscure genre of music. Largely sample-based, it is characterized by an obsession with retro aesthetics, new technology, and consumerism. Songs range from upbeat to hypnogogic. They sometimes incorporate sound marks. Vaporwave musicians have monikers like Saint Pepsi and Macintosh Plus. Gucci Mane is a rap star and actor from Atlanta. All nine of his studio albums have placed on the Billboard Top 200. In 2013, he starred alongside James Franco and Selena Gomez in Spring Breakers, which competed for the Golden Lion award at the sixty-ninth Venice International Film Festival. Stuart Helm is an artist who formerly used the moniker King VelVeeda. Until the early 2000s, he operated cheeseygraphics.com, a website that sold his bawdy-themed art and advertised commercial art services. Horst Simco is a recording artist from Houston who goes by Riff Raff. His collection of tattoos includes the NBA logo, the MTV logo, and the BET logo. -

Está Tudo Em Suas Mãos”: O Desenvolvimento Do Movimento Vaporwave Na Internet1

Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação XIX Congresso de Ciências da Comunicação na Região Nordeste – Fortaleza - CE – 29/06 a 01/07/2017 “Está Tudo Em Suas Mãos”: O Desenvolvimento do Movimento Vaporwave na Internet1 Gabriel Holanda MONTEIRO2 Liana Viana do AMARAL3 José Riverson Araújo Cysne RIOS4 Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE Resumo O seguinte artigo pretende analisar o Vaporwave enquanto movimento artístico (por meio de suas nuances musicais, estéticas e ideológicas) e fenômeno cibercultural através de uma análise de seu histórico, levando ao seu recente declínio ocasionado por diversos fatores, dentre eles a apropriação pela emissora MTV, que utilizou a estética do movimento em sua nova identidade visual de marca em 2015. A fundamentação teórica do trabalho abordará conceitos de indústria cultural, democratização da produção cultural e remediação midiática, entre outros. Foram usados autores como Bolter, Anderson, Tanner, Ramos, Duarte e Kellner, de suma importância para a estruturação da pesquisa. Palavras-Chave: Vaporwave; MTV; Cibercultura; Indústria Cultural; Remediação Midiática. Introdução No ciberespaço surgem as tendências mais improváveis possíveis. Desde os memes até as obras de arte digitais, de teorias conspiratórias a tutoriais inusitados, tudo pode acontecer. No meio disso, eis que no início da década surge uma tendência estética e musical que mais tarde se configuraria como um movimento artístico denominado Vaporwave, com suas esculturas de cabeças sobrevoando em fundos degradês junto a garrafas de água Fiji e personagens do jogo Sonic rodando, em um visual que poderia ser facilmente categorizado como “brega”, além de suas músicas desconcertantes que invocam desde sons de sistemas operacionais com vozes robóticas até a voz de uma apresentadora de infomercial. -

Music That Laughs 2017

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Adam Harper Music that laughs 2017 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Harper, Adam: Music that laughs. In: POP. Kultur und Kritik, Jg. 6 (2017), Nr. 1, S. 60– 65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1817. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:101:1-2020052211120328716628 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under a Deposit License (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, non-transferable, individual, and limited right for using this persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses document. This document is solely intended for your personal, Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für non-commercial use. All copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute, or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the conditions of vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder use stated above. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

University of Birmingham from Microsound to Vaporwave

University of Birmingham From Microsound to Vaporwave Born, Georgina; Haworth, Christopher DOI: 10.1093/ml/gcx095 Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Born, G & Haworth, C 2018, 'From Microsound to Vaporwave: internet-mediated musics, online methods, and genre', Music and Letters, vol. 98, no. 4, pp. 601–647. https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Checked for eligibility: 30/03/2017 This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Music and Letters following peer review. The version of record Georgina Born, Christopher Haworth; From Microsound to Vaporwave: Internet-Mediated Musics, Online Methods, and Genre, Music and Letters, Volume 98, Issue 4, 1 November 2017, Pages 601–647 is available online at: https://doi.org/10.1093/ml/gcx095 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. -

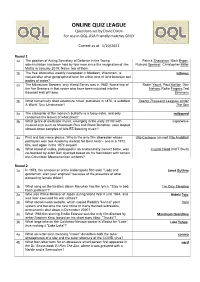

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions Set by David Dixon for Use in OQL-USA Friendly Matches ONLY

ONLINE QUIZ LEAGUE Questions set by David Dixon For use in OQL-USA Friendly matches ONLY Correct as at 1/10/2021 Round 1 1a The position of Acting Secretary of Defense in the Trump Patrick Shanahan, Mark Esper, administration has been held by four men since the resignation of Jim Richard Spencer, Christopher Miller Mattis in January 2019. Name two of them 1b The free alternative weekly newspaper in Madison, Wisconsin, is Isthmus named after what geographical term for a thin strip of land between two bodies of water? 2a The Milwaukee Brewers' only World Series was in 1982. Name two of Robin Yount, Paul Molitor, Don the five Brewers in that roster who have been inducted into the Nelson, Rollie Fingers,Ted Baseball Hall of Fame. Simmons 2b What numerically titled adventure novel, published in 1870, is subtitled Twenty Thousand Leagues Under A World Tour Underwater? The Sea 3a The caterpillar of the monarch butterfly is a fussy eater, and only milkweed consumes the leaves of what plant? 3b What genre of electronic music, emerging in the early 2010s with vaporwave musical acts such as Macintosh Plus and Blank Banshee, uses looped, slowed-down samples of 80s EZ-listening music? 4a First and last name please. Who is the only film character whose Vito Corleone (accept Vito Andolini) portrayals won two Academy Awards for Best Actor-- one in a 1972 film, and again in the 1974 sequel? 4b What brand of vodka, packaged in an anatomically-correct bottle, was Crystal Head (NOT Skull) co-founded by actor Dan Aykroyd based on his fascination with certain -

Vaporwave: Microculturas Artísticas Na Era Da Internet

Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisual e Publicidade Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso em Publicidade e Propaganda Orientadora: Isabella Lara Oliveira Vaporwave: Microculturas artísticas na era da internet. Caio Roberto Costa Caldas 14/0055983 Brasília - DF 1/2018 Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisual e Publicidade Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso em Publicidade e Propaganda Vaporwave: Microculturas artísticas na era da internet. Caio Roberto Costa Caldas Monografia apresentada como pré-requisito para obtenção do grau de Bacharel em Comunicação Social do curso de Publicidade e Propaganda, da Faculdade de Comunicação, Universidade de Brasília, tendo como orientadora a professora Isabella de Oliveira Lara. Brasília - DF 1/2018 1 Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Comunicação Departamento de Audiovisual e Publicidade Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso em Publicidade e Propaganda Caio Roberto Costa Caldas - 14/0055983 Banca Examinadora ____________________________________ Professora Isabella Lara Oliveira (Orientadora) ____________________________________ Professor Wagner Antônio Rizzo (Examinador) ____________________________________ Professor Rafael Dietzsch (Examinador) ____________________________________ Professora Selma Regina Nunes Oliveira (Examinadora suplente) 2 “A teoria e cultura pós-modernas celebram o fim da história e, de certa forma, o fim da razão, renunciando a nossa capacidade de entender e encontrar sentido até no que não tem sentido.” Manuel Castells, -

The Influence of Internet Culture on the Shifts in Aesthetics. a Practice-Based Approach to Vaporwave

VAKARŲ ESTETIKA IR MENO FILOSOFIJA The Influence of Internet Culture on the Shifts in Aesthetics. A Practice-based Approach to Vaporwave VYGINTAS ORLOVAS Vilnius Academy of Arts [email protected] The roots of the cultural object called vaporwave are often traced to the year 2009, however, the qualities that define it are still being discussed in both the discourse of popular culture as well as in an academic context. Ranging from being defined as a microgenre of electronic music, a meme, an art movement, a critique of capitalism to a being defined as a form of pure aesthetics it remains a multifaceted object for research. In this paper, I explore examples of vaporwave in order to distinguish the methods and strategies used for creating something that is called vaporwave, rather than in an attempt to label it as some particular thing. As a further step in this inquiry to vaporwave, I document an attempt to apply these methods and strategies that resulted in a published music album. A practice- based approach to analyzing vaporwave by creating and publishing it does help to understand some core qualities of it. Keywords: vaporwave, aesthetics, plunderphonics, internet culture, practice-based research. Introduction: Definitions and roots scribing it through precise definitions and distinct qualities what would they be? Often Metaphorically speaking vaporwave can be it is described as a microgenre of electronic described as „the muzak that plays in an music, a meme, an art movement, a critique elevator in a mall in a futuristic Japanese of capitalism or as a form of aesthetics. -

Altered States: the American Psychedelic Aesthetic

ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC A Dissertation Presented by Lana Cook to The Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April, 2014 1 © Copyright by Lana Cook All Rights Reserved 2 ALTERED STATES: THE AMERICAN PSYCHEDELIC AESTHETIC by Lana Cook ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University, April, 2014 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation traces the development of the American psychedelic aesthetic alongside mid-twentieth century American aesthetic practices and postmodern philosophies. Psychedelic aesthetics are the varied creative practices used to represent altered states of consciousness and perception achieved via psychedelic drug use. Thematically, these works are concerned with transcendental states of subjectivity, psychic evolution of humankind, awakenings of global consciousness, and the perceptual and affective nature of reality in relation to social constructions of the self. Formally, these works strategically blend realist and fantastic languages, invent new language, experimental typography and visual form, disrupt Western narrative conventions of space, time, and causality, mix genres and combine disparate aesthetic and cultural traditions such as romanticism, surrealism, the medieval, magical realism, science fiction, documentary, and scientific reportage. This project attends to early exemplars of the psychedelic aesthetic, as in the case of Aldous Huxley’s early landmark text The Doors of Perception (1954), forgotten pioneers such as Jane Dunlap’s Exploring Inner Space (1961), Constance Newland’s My Self and I (1962), and Storm de Hirsch’s Peyote Queen (1965), cult classics such as Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), and ends with the psychedelic aesthetics’ popularization in films like Roger Corman’s The Trip (1967).