The Entanglement of Climate Change, Capitalism and Oppression in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Cecilia Mancuso [email protected] Office: One Bow Street #340 Office Hours: TBD and by Appointment – Please Visit Cecimancuso.Youcanbook.Me

Cecilia Mancuso [email protected] Office: One Bow Street #340 Office Hours: TBD and by appointment – please visit cecimancuso.youcanbook.me Contemporary Science Fiction and Critical Theory [COURSE DESCRIPTION] Science fiction (sf) has often been defined as a “literature of ideas” – everything from a vector for hard scientific knowledge to a soft-science thought experiment. But which “ideas” is sf particularly good at communicating, and why those ideas? In this course, students will familiarize themselves with a number of theoretical and literary-critical approaches to the study of literature through the lens of contemporary science fiction and its principal genres (dystopia, cyberpunk, space opera, afrofuturism, and hard sf). This course also takes a multimedia approach to sf as a genre, including novels, short stories, TV, and video games as primary texts. Students will leave the tutorial with a 20-25 page research-based junior essay which engages substantively with literary theory and a working methodology for how to approach producing extended-length scholarly papers. [REQUIRED COURSE TEXTS] • N.K. Jemisin, The Fifth Season (ISBN9780316229296) • Cixin Liu, The Three-Body Problem (ISBN 9780765382030) • Annalee Newitz, Autonomous (ISBN 978065392077) • Ann Leckie, Ancillary Justice (ISBN 9780316246620) [COURSE MATERIALS ENCOURAGED BUT NOT REQUIRED] • Supergiant Games, Transistor (available for iOS, PC, and Mac) • A Netflix subscription (or access to one) PDFs of all other course readings will be made available either as paper copies or through the course site. [GRADING] • Participation and weekly assignments: 10% • First paper, 5-7 pages, due Feb 8 by 5pm: 15% • Proposal & annotated bibliography, 2 pages and 8-10 sources, due March 1 by 5pm: 15% • Rough draft, 15-20 pages, due April 11 by 5pm: 20% • Final draft, 20-25 pages, due May 2 by 5pm: 40% [SOME EXPECTATIONS] 1. -

Science Fiction List Literature 1

Science Fiction List Literature 1. “The Unparalleled Adventure of One Hans Pfaall,” Edgar Allan Poe (1835, US, short story) 2. Looking Backward, Edward Bellamy (1888, US, novel) 3. A Princess of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1912, US, novel) 4. Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1915, US, novel) 5. “The Comet,” W.E.B. Du Bois (1920, US, short story) 6. Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury (1951, US, novel) 7. Limbo, Bernard Wolfe (1952, US, novel) 8. The Stars My Destination, Alfred Bester (1956, US, novel) 9. Venus Plus X, Theodore Sturgeon (1960, US, novel) 10. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Philip K. Dick (1968, US, novel) 11. The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula K. Le Guin (1969, US, novel) 12. The Female Man, Joanna Russ (1975, US, novel) 13. “The Screwfly Solution,” “The Girl Who Was Plugged In,” “The Women Men Don’t See,” “Houston, Houston Do You Read?”, James Tiptree Jr./Alice Sheldon (1977, 1973, 1973, 1976, US, novelettes, novella) 14. Native Tongue, Suzette Haden Elgin (1984, US, novel) 15. Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand, Samuel R. Delany (1984, US, novel) 16. Neuromancer, William Gibson (1984, US-Canada, novel) 17. The Handmaid’s Tale, Margaret Atwood (1985, Canada, novel) 18. The Gilda Stories, Jewelle L. Gómez (1991, US, novel; extended edition 2016) 19. Dawn, Octavia E. Butler (1987, US, novel); Parable of the Sower, Butler (1993, US, novel); Bloodchild and Other Stories, Butler (1995, US, short stories; extended edition 2005) 20. Red Spider, White Web, Misha Nogha/Misha (1990, US, novel) 21. The Rag Doll Plagues, Alejandro Morales (1991, US, novel) 22. -

The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First Century American Fiction Edited by Joshua Miller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83827-6 — The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First Century American Fiction Edited by Joshua Miller Frontmatter More Information -- Reading lists, course syllabi, and prizes include the phrase “twenty-first-century American literature,” but no critical consensus exists regarding when the period began, which works typify it, how to conceptualize its aesthetic priorities, and where its geographical boundaries lie. Considerable criticism has been published on this extraordinary era, but little programmatic analysis has assessed comprehensively the literary and critical/theoretical output to help readers navigate the labyrinth of critical pathways. In addition to ensuring broad coverage of many essential texts, The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First- Century American Fiction offers state-of-the-field analyses of contemporary narrative studies that set the terms of current and future research and teaching. Individual chapters illuminate critical engagements with emergent genres and concepts, including flash fiction, speculative fiction, digital fiction, alternative temporalities, Afro-Futurism, ecocriticism, transgender/queer studies, anti- carceral fiction, precarity, and post-9/11 fiction. . is Associate Professor of English at the University of Michigan. He is the author of Accented America: The Cultural Politics of Multilingual Modernism (2011), editor of The Cambridge Companion to the American Modernist Novel (2015), and coeditor of Languages of Modern Jewish Cultures: Comparative Perspectives (2016). © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-83827-6 — The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First Century American Fiction Edited by Joshua Miller Frontmatter More Information THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO TWENTY-FIRST- CENTURY AMERICAN FICTION EDITED BY JOSHUA L. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

Afrofuturism and Generational Trauma in N. K. Jemisin's

Department of English Afrofuturism and Generational Trauma in N. K. Jemisin‘s Broken Earth Trilogy Imogen Bagnall Master‘s Degree Thesis Literature Spring 2021 Supervisor: Joakim Wrethed Abstract N. K. Jemisin‘s Broken Earth Trilogy explores the methods and effects of systemic oppression. Orogenes are historically oppressed and dehumanised by the wider society of The Stillness. In this thesis, I will be exploring the ways in which trauma experienced by orogenes is repeated through generations, as presented through Essun‘s varied and complex relationships with her children, and with the Fulcrum Guardian Schaffa. The collective trauma of orogenes is perpetuated through different direct and indirect actions in a repetitive cycle, on societal, interpersonal and familial levels. My reading will be in conversation with theories of trauma literature and cultural trauma, and will be informed by Afrofuturist cultural theory. Although science fiction and fantasy encourage the imagination, worldbuilding is inherently influenced by lived experiences. It could thus be stated that the trauma experienced by orogenes is informed by the collective trauma of African-Americans, as experienced by N. K. Jemisin. Afrofuturism is an aesthetic mode and critical lens which prioritises the imagining of a liberated future. Writing science fiction and fantasy through an Afrofuturist aesthetic mode encourages authors to explore forms of collective trauma as well as methods of healing. Jemisin creates an explicit parallel between the traumatic African-American experience and that of orogenes. Afrofuturist art disrupts linear time and addresses past and present trauma through the imagining of the future. The Broken Earth Trilogy provides a blueprint for the imagined liberation of oppressed groups. -

LFA Library: New Materials (October - November 2017)

LFA Library: New Materials (October - November 2017) *Books marked with an asterisk are related to the current HOS Symposium Topic. Overdrive eBooks (Red= Fiction; Black= Non-Fiction) Title Author American Street Ibi Zoboi (Finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction) *Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst Robert M. Sopolsky *Feeling Beauty: The Neuroscience of Aesthetic Experience G. Gabrielle Starr The Future is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia Masha Gessen (Winner of the National Book Award for Non Fiction) The General vs. the President: MacArthur and Truman at the Brink of Nuclear War H.W. Brands Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow Yuval Noah Harari History of Wolves: A Novel Emily Fridlund (Finalist for the Man Booker Prize) Little & Lion Brandy Colbert Miss Burma Charmaine Craig *The River of Consciousness Oliver Sacks Swing Time Zadie Smith (Finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for Fiction; Longlisted for the Man Booker Prize) We Will Not Be Silent: The White Rose Student Resistance Movement That Defied Adolf Hitler Russell Freedman (Winner of an American Library Association Informational Book Honor) The Windfall Diksha Basu You Don’t Have to Say You Love Me: A Memoir Sherman Alexie Print Collection (Red= Fiction; Black= Non-Fiction) Title Author The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation v.2: The Kingdom on the Waves M.T. Anderson (Winner of the American Library Association’s Award for Best Book for Young Adults; Sequel to the National Book Award Winner, The Pox Party) Astrophysics for People in a Hurry Neil deGrasse Tyson Beowulf (A Graphic Novel) Santiago Garcia Bix: The Definitive Biography of a Jazz Legend Jean Pierre Lion The Broken Earth Trilogy Book 1: The Fifth Season N.K. -

Audiofile Editors Announce 2016 Best Audiobooks

Press Release--EMBARGOED UNTIL DECEMBER 1, 2016 AudioFile Editors Announce 2016 Best Audiobooks AudioFile celebrates standout audiobook performances with a special EZine, blog partners, and listener sweepstakes, recognizing the growing diversity and popularity of audiobooks. (Portland, Maine, December 1, 2016) AudioFile Magazine announced the winners of the 2016 Best Audiobooks today, recognizing standout audiobook performances in nine categories. “This year’s lineup includes diverse, deeply personal, and timely storytelling and celebrates the skill and dedication of the narrators as well as everyone who works behind the scenes to bring us the art form of the audiobook,” said Robin Whitten, Editor and Founder of AudioFile Magazine. The 2016 Best Audiobooks are selected by AudioFile editors in nine genres: Fiction, Nonfiction & Culture, Memoir, Biography & History, Mystery & Suspense, Science Fiction & Fantasy, Children & Family Listening, Young Adult, and Romance. AudioFile Magazine editors review and recommend audiobooks weekly and maintain an archive of more than 40,000 reviews. Reviews are available in print on their website, www.AudioFilemagazine.com, and via e-newsletters and daily Sound Reviews, which you can subscribe to directly in iTunes or follow and share with friends on SoundCloud. Now in its seventh year, the annual ‘Best Audiobooks’ list highlights the ever-expanding genre of audiobooks, celebrating 126 audio titles, all of which are the result of inspiring writers and narrators who have combined their talents to create compelling listening for all ages. This year’s winners include authors Stephen King, Amy Schumer, Stephenie Meyer, Kate DiCamillo, Rick Riordan, William Shatner, Eric Ripert, Cory Booker, Glennon Doyle Melton, Colson Whitehead, and Jacqueline Woodson, among many others. -

Issue 388, July 2018

President’s Column Why Thanos Flunked Sociology MONTH Parsec Meeting Minutes Fantastic Artist Of The Month Right the First Time - Harlan Ellison Brief Bios Belated reflections on the nebula awards Parsec Meeting Schedule Kumori And The Lucky Cat Two Alpha book signings President’s Column exceptions, I can tick on one gnarled hand.” Is it possible I have become an old codger? Do I limp around the house and chant,“These damn kids don’t read and write anymore? They watch movies and play video games that they then make into movies. They have forsaken the world of science fiction for the world of fantasy and horror?” I do not. It is a fact that I am more at ease with change than many people a quarter my age. I also realize that what I think doesn’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Read, write, watch and enjoy whatever it is that stokes your passion. I finally gave up mucking around for an answer. Decided to just let it be. To apprecite and study. I just read and enjoyed the thirteen Lancelot Biggs stories written from 1940 until 1945 in Amazing Stories, Fantastic Stories, and Weird Tales by Nelson S. Bond. Next, who knows, I might even begin a story that was written after I was born. I thought you all should know as President of Parsec and co-editor of Sigma, I am not against printing articles about present-day science fiction. I hope that someone will take it as a challenge and write something for the Parsec newsletter. -

Science Fiction & Fantasy Book Group List 2010 to 2020.Xlsx

Science Fiction & Fantasy Book List 2010-2020 Date discussed Title Author Pub Date Genre Tuesday, August 17, 2010 Eyes of the Overworld Jack Vance 1966 Fantasy Tuesday, September 21, 2010 Boneshaker Cherie Priest 2009 Science Fiction/Steampunk Tuesday, October 19, 2010 Hood (King Raven #1) Steve Lawhead 2006 Fantasy/Historical Fiction Tuesday, November 16, 2010 Hyperion (Hyperion Cantos #1) Dan Simmons 1989 Science Fiction Tuesday, December 21, 2010 Swords and Deviltry (Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser #1) Fritz Leiber 1970 Fantasy/Sword and Sorcery Tuesday, January 18, 2011 Brave New World Aldous Huxley 1931 Science Fiction/Dystopia Tuesday, February 15, 2011 A Game of Thrones (A Song of Ice and Fire, Book 1) George R.R. Martin 1996 Fantasy Tuesday, March 15, 2011 Hull Zero Three Greg Bear 2010 Science Fiction Tuesday, April 19, 2011 The Lies of Locke Lamora (Gentleman Bastard, #1) Scott Lynch 2006 Fantasy Tuesday, May 17, 2011 Never Let Me Go Kazuo Ishiguro 2005 Science Fiction/Dystopia Tuesday, June 21, 2011 The Name of the Wind (The Kingkiller Chronicle #1) Patrick Rothfuss 2007 Fantasy Tuesday, July 19, 2011 Old Man's War (Old Man's War, #1) John Scalzi 2005 Science Fiction NO MEETING Tuesday, August 16, 2011 Wednesday, September 07, 2011 Something Wicked This Way Comes (Green Town #2) Ray Bradbury 1962 Fantasy Wednesday, October 05, 2011 Altered Carbon (Takeshi Kovacs #1) Richard Morgan 2002 Science Fiction Wednesday, November 02, 2011 Prospero's Children Jan Siegel 1999 Fantasy Wednesday, December 07, 2011 Replay Ken Grimwood 1986 Science Fiction/Time Travel Wednesday, January 04, 2012 Raising Stony Mayhall Daryl Gregory 2011 Fantasy/Horror/Zombies Wednesday, February 01, 2012 The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress Heinlein, Robert 1966 Science Fiction Wednesday, March 07, 2012 Talion: Revenant Michael A. -

Download Program Book

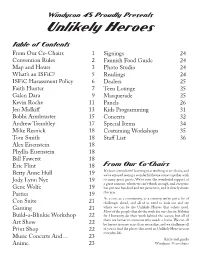

Windycon 45 Proudly Presents Unlikely Heroes Table of Contents From Our Co-Chairs 1 Signings 24 Convention Rules 2 Fannish Food Guide 24 Map and Hours 3 Photo Studio 24 What’s an ISFiC? 5 Readings 24 ISFiC Harassment Policy 6 Dealers 25 Faith Hunter 7 Teen Lounge 25 Galen Dara 9 Masquerade 25 Kevin Roche 11 Panels 26 Jen Midkiff 13 Kids Programming 31 Bobbi Armbruster 15 Concerts 32 Andrew Trembley 17 Special Items 34 Mike Resnick 18 Costuming Workshops 35 Tom Smith 18 Staff List 36 Alex Eisenstein 18 Phyllis Eisenstein 18 Bill Fawcett 18 From Our Co-Chairs Eric Flint 18 It’s been a wonderful learning year working as co-chairs, and Betty Anne Hull 19 we’ve enjoyed seeing a wonderful theme come together with so many great guests. We’ve seen the wonderful support of Jody Lynn Nye 19 a great concom, whom we can’t thank enough, and everyone Gene Wolfe 19 has put one hundred and ten percent in, and it clearly shows Parties 19 this year. As a con, as a community, as a country, we’ve got a lot of Con Suite 21 challenges ahead, and all of us need to look out and see where we can be the Unlikely Heroes that others need. Gaming 21 Most of the people that do the work for our charity, Habitat Build-a-Blinkie Workshop 22 for Humanity, do their work behind the scenes, but all of them are heroes to someone who needs a home. We can all Art Show 22 be heroes in more ways than we realize, and we challenge all of you to find the places that need an Unlikely Hero in your Print Shop 22 everyday life. -

Master´S Thesis Project Cover Page for the Master's Thesis

The Faculty of Humanities Master´s Thesis Project Cover page for the Master’s thesis Submission January: [year] June: 2020 Other: [Date and year] Supervisor: Bryan Yazell Department: HUM Title, Danish: Title, English: On Magic: How Magic Systems in Modern Fantasy Disrupt Power Structures of Race, Class, and Gender Min./Max. number of characters: 144,000 – 192,000 Number of characters in assignment1: (60 – 80 normal pages) 169,570 (1 norm page = 2400 characters incl. blank spaces) Please notice that in case your Master’s thesis project does not meet the minimum/maximum requirements stipulated in the curriculum your assignment will be dismissed and you will have used up one examination attempt. (Please The Master’s thesis may in anonymized form be used for teaching/guidance of mark) future thesis students __X__ Solemn declaration I hereby declare that I have drawn up the assignment single-handed and independently. All quotes are marked as such and duly referenced. The full assignment or parts thereof have not been handed in as full or partial fulfilment of examination requirements in any other courses. Read more here: http://www.sdu.dk/en/Information_til/Studerende_ved_SDU/Eksamen.aspx Handed in by: First name: Helen Last name: Jones Date of birth: 02/02/1996 1 Characters are counted from the first character in the introduction until and including the last character in the conclusion. Footnotes are included. Charts are counted with theirs characters. The following is excluded from the total count: abstract, table of contents, bibliography, list of references, appendix. For more information, see the examination regulations of the course in the curriculum.