The Voices of Girl Child Soldiers C O L O M B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jul Aug 2016 Newsletter WEB VERSION

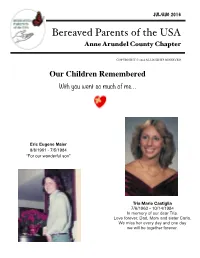

JUL/AUG 2016 Bereaved Parents of the USA Anne Arundel County Chapter COPYRIGHT © 2016 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Our Children Remembered With you went so much of me… Eric Eugene Maier 8/8/1961 - 7/5/1984 “For our wonderful son” Tria Marie Castiglia 7/6/1963 - 10/14/1984 In memory of our dear Tria. Love forever, Dad, Mom and sister Carla. We miss her every day and one day we will be together forever. JUL/AUG 2016 Healing with my Hands In September of 2010 my 25 year old son went into the hospital with a flare up of the Crohn's disease that had been interfering with his life for over 12 years. We expected a 3-4 day stay which was his norm. After a few days of fluids and steroids he would be on his way to a quick recovery. What really happened is that he barely made it home after 2 1/2 months of intensive care and rehab, multiple surgeries, dozens of procedures, a weight loss of 50 pounds and the loss of the life he knew. For this Mama it was the most frightening, agonizing, and heartbreaking time of her life. I plummeted into a dark abyss of which I had never experienced before. Fear and anxiety plagued my every waking moment. Without the aid of a sleeping pill, it also visited me in my sleep. When Tommy died suddenly in March of 2011, I fell even deeper into the abyss. I cared not for surviving and thought endlessly of joining him. Along with my intense need to see him again, my heart and soul needed a respite from the excruciating heartbreak. -

George Gebhardt Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

George Gebhardt 电影 串行 (大全) The Dishonored https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-dishonored-medal-3823055/actors Medal A Rural Elopement https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-rural-elopement-925215/actors The Fascinating https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-fascinating-mrs.-francis-3203424/actors Mrs. Francis Mr. Jones at the https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mr.-jones-at-the-ball-3327168/actors Ball A Woman's Way https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-woman%27s-way-3221137/actors For Love of Gold https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/for-love-of-gold-3400439/actors The Sacrifice https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-sacrifice-3522582/actors The Honor of https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-honor-of-thieves-3521294/actors Thieves The Greaser's https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-greaser%27s-gauntlet-3521123/actors Gauntlet The Tavern https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-tavern-keeper%27s-daughter-1756994/actors Keeper's Daughter The Stolen Jewels https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-stolen-jewels-3231041/actors Love Finds a Way https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/love-finds-a-way-3264157/actors An Awful Moment https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/an-awful-moment-2844877/actors The Unknown https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-unknown-3989786/actors The Fatal Hour https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-fatal-hour-961681/actors The Curtain Pole https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-curtain-pole-1983212/actors -

Stern Book4print Rev.Pdf

HOME ECONOMICS Stern_final_rev.indb 1 3/28/2008 3:50:37 PM Stern_final_rev.indb 2 3/28/2008 3:50:37 PM HOME ECONOMICS Domestic Fraud in Victorian England R EBECCA S TE R N The Ohio State University Press / C o l u m b u s Stern_final_rev.indb 3 3/28/2008 3:50:40 PM Copyright ©2008 by The Ohio State University. All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stern, Rebecca. Home economics : domestic fraud in Victorian England / Rebecca Stern. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8142-1090-1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Fraud in literature. 2. English literature—19th century—History and criticism. 3. Popular literature—Great Britain—History and criticism. 4. Home economics in literature 5. Swindlers and swindling in literature. 6. Capitalism in literature. 7. Fraud in popular cul- ture. 8. Fraud—Great Britain—History—19th century. I. Title. PR468.F72S74 2008 820.9'355—dc22 2007035891 This book is available in the following editions: Cloth (ISBN 978-0-8142-1090-1) CD (ISBN 978-0-8142-9170-2) Cover by Janna Thompson Chordas Text design and typesetting by Jennifer Shoffey Forsythe Type set in Adobe Garamond Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials. ANSI Z39.48-1992. 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Stern_final_rev.indb 4 3/28/2008 3:50:40 PM For my parents, Annette and Mel, who make all the world a home Stern_final_rev.indb 5 3/28/2008 3:50:40 -

Women in Hebrew and Ancient Near Eastern Law

Studia Antiqua Volume 3 Number 1 Article 5 June 2003 Women in Hebrew and Ancient Near Eastern Law Carol Pratt Bradley Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Bradley, Carol P. "Women in Hebrew and Ancient Near Eastern Law." Studia Antiqua 3, no. 1 (2003). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol3/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Women in Hebrew and Ancient Near Eastern Law Carol Pratt Bradley The place of women in ancient history is a subject of much scholarly interest and debate. This paper approaches the issue by examining the laws of ancient Israel, along with other ancient law codes such as the Code of Hammurabi, the Laws of Urnammu, Lipit-Ishtar, Eshnunna, Hittite, Middle Assyrian, etc. Because laws reflect the values of the societies which developed them, they can be beneficial in assessing how women functioned and were esteemed within those cultures. A major consensus among scholars and students of ancient studies is that women in ancient times were second class, op- pressed, and subservient to men. This paper approaches the subject of the status of women anciently by examining the laws involving women in Hebrew law as found in the Old Testament, and in other law codes of the ancient Near East. -

Possibility-Space and Its Imaginative Variations in Alice Munro’S Short Stories

POSSIBILITY-SPACE AND ITS IMAGINATIVE VARIATIONS IN ALICE MUNRO’S SHORT STORIES Ulrica Skagert . Possibility-Space and Its Imaginative Variations in Alice Munro’s Short Stories Ulrica Skagert Stockholm University ©Ulrica Skagert, Stockholm 2008 ISBN 978-91-7155-770-4 Cover photograph: Edith Maybin. Courtesy of The New Yorker. To the memory of my father who showed me the pleasures of reading. Abstract Skagert, Ulrica, 2008. Possibility-Space and Its Imaginative Variations in Alice Munro’s Short Stories. Pp.192. Stockholm: ISBN: 978-91-7155-770-4 With its perennial interest in the seemingly ordinary lives of small-town people, Alice Munro’s fiction displays a deceptively simple surface reality that on closer scrutiny reveals intricate levels of unexpected complexity about the fundamentals of human experience: love, choice, mortality, faith and the force of language. This study takes as its main purpose the explora- tion of Munro’s stories in terms of the intricacy of emotions in the face of commonplace events of life and their emerging possibilities. I argue that the ontological levels of fiction and reality remain in the realm of the real; these levels exist and merge as the possibilities of each other. Munro’s realism is explored in terms of its connection to possibilities that arise out of a particu- lar type of fatality. The phenomenon of possibility permeates Munro’s stories. An inves- tigation of this phenomenon shows a curious paradox between possibility and necessity. In order to discuss the complexity of this paradox I introduce the temporal/spatial concept of possibility-space and notions of the fatal. -

Staging Executions: the Theater of Punishment in Early Modern England Sarah N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Staging Executions: The Theater of Punishment in Early Modern England Sarah N. Redmond Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY THE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES “STAGING EXECUTIONS: THE THEATER OF PUNISHMENT IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND” By SARAH N. REDMOND This thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sarah N. Redmond, Defended on the 2nd of April, 2007 _______________________ Daniel Vitkus Professor Directing Thesis _______________________ Gary Taylor Committee Member _______________________ Celia Daileader Committee Member Approved: _______________________ Nancy Warren Director of Graduate Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Daniel Vitkus, for his wonderful and invaluable ideas concerning this project, and Dr. Gary Taylor and Dr. Celia Daileader for serving on my thesis committee. I would also like to thank Drs. Daileader and Vitkus for their courses in the Fall 2006, which inspired elements of this thesis. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures . v Abstract . vi INTRODUCTION: Executions in Early Modern England: Practices, Conventions, Experiences, and Interpretations . .1 CHAPTER ONE: “Blood is an Incessant Crier”: Sensationalist Accounts of Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Print Culture . .11 CHAPTER TWO “Violence Prevails”: Death on the Stage in Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy and Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy . -

E C H O E S 1 L U M O E V

E M U L 1 O V of memory e c h o e s UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM score echoes of memory - volume United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, WashinGton, D.C. 1 spine trim United States Holocaust Memorial Museum 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place, SW Washington, DC 20024-2126 ECHOES L U M O E of memory V 1 STORIES FROM THE MEMORY PROJECT UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM This program has been made possible in part with support from the Helena Rubinstein Foundation. • CONTENTS Echoes of Memory LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR ................................................................ i FOREWORD ...................................................................................... iii Elizabeth Anthony, Memory Project Coordinator INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. v Margaret Peterson, Memory Project Instructor ERIKA ECKSTUT ................................................................................ 1 Teach Love, Not Hate .................................................................... 2 Lasting Memory .......................................................................... 4 FRANK EPHRAIM ................................................................................ 5 Sardines .................................................................................... 6 Lunch Trade * .............................................................................. 7 Teapot in a Tempest * .................................................................... 12 MANYA FRIEDMAN -

"CAIN ROSE up AGAINST His BROTHER ABEL and KILLED HIM": MURDER OR MANSLAUGHTER?

"CAIN ROSE UP AGAINST His BROTHER ABEL AND KILLED HIM": MURDER OR MANSLAUGHTER? Irene Merker Rosenberg* Yale L. Rosenberg** I. INTRODUCTION The world's first case of man slaying man,' and, indeed, the earliest recorded crime,2 is dealt with in a series of terse verses in Genesis, the first of the five Books of the Torah,3 the Jewish Bible: * Royce R. Till Professor of Law, University of Houston Law Center. B.A., College of the City of New York, 1961; LL.B., New York University School of Law, 1964. ** A.A. White Professor of Law, University ofHouston Law Center. B.A., Rice University, 1959; LL.B., New York University School of Law, 1964. We extend special thanks to Rabbi Arnold Greenman for his invaluable assistance on the Jewish law segment of this article. Thanks also to Harriet Richman, Director, Faculty Research Services, University of Houston Law Library, and the students under her supervision, especially Stewart Schmella, Class of 2001, University of Houston Law Center. In addition, we have profited greatly from the suggestions of our colleagues in the "Thursday Thoughts" faculty workshop, especially Joseph Sanders. In our citations to Jewish law materials, we have used English translations whenever possible, verifying their accuracy by comparing them with the original sources. In some cases, however, this means that the same word will be transliterated differently by various translators. For example, the Hebrew letter equivalents of"s" and "t" are sometimes used interchangeably. With respect to Hebrew and Aramaic sources that have not been translated into English, we of course vouch for the accuracy of the translations. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Rise of the Feminine Voice and a Renewed Consciousness in Spanish Contemporary Literature "Cronica Del Desamor" Por Rosa Montero

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1998 Rise of the feminine voice and a renewed consciousness in Spanish contemporary literature "Cronica del Desamor" por Rosa Montero Rhonda L. Moore The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Moore, Rhonda L., "Rise of the feminine voice and a renewed consciousness in Spanish contemporary literature "Cronica del Desamor" por Rosa Montero" (1998). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3448. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3448 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of MONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission ^ No, I do not grant permission Author's Signature^^^^^^^ Date 7^/^^ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. THE RISE OF THE FEMININE VOICE AND A RENEWED CONSCIOUSNESS IN SPANISH CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE: CRONICA DEL DESAMOR POR ROSA MONTERO by Rhonda L. -

Luke Mivers' Harvest

Luke Mivers' Harvest Swan, N. Walter (Nathaniel Walter) (1834-1884) University of Sydney Library Sydney 2000 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/ ©Introduction Harry Heseltine; Electronic Text, University of New South Wales Press; University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by University of New South Wales Press Sydney 1991 Colonial Texts Series General Editorial Committee: Harry Heseltine Paul Eggert Joy Hooton Originally published serially in the Sydney Mail, March-July, 1879. The body of the text was received from Paul Eggert at the Scholarly Editions Centre in Pagemaker5 format. These files were exported to text format and encoded manually to TEI.2 conformance by C.Cole at . Any errors resulting from the manual encoding of the text are the responsibility of . Known problem in conversion to text file from Pagemaker5 is stripping of dashes other than hyphens. Replaced manually. All quotation marks retained as data Full list of editor's emendations at the end of the text. First Published: 1879 Australian Etexts novels 1840-1879 prose fiction 8th September 2000 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Luke Mivers' Harvest Sydney University of New South Wales Press 1991 Images N.W. Swan's Ireland [Map p.xiv] N.W. Swan's Victoria [Map p. 284] General Editorial Foreword The Colonial Texts Series provides reliable texts of nineteeth century Australian literary works which have been out of print or difficult of access throughout most of the present century. The selection of titles is deliberately slanted towards works of fiction-novels and collections of short stories—because their length has militated even more than in the case of verse against their re-publication. -

Outdoor No Contact Games and Activities Ideas - Primary

Physical, Social and Arty Outdoor No Contact Games and Activities Ideas - Primary Here are 50 ideas for physical, social and arty outdoor games and activities. They are divided into Physical, Social, and Arty sections to reflect their main theme, although they might cover two or three of the areas. This is not to suggest that all the children’s time should be directed and guided. It’s recognised that it is also important to let the children create their own games and activities and have time to be creative. Thank you to everyone who gave ideas. Physical Game 1 - Riverbank In this simple game, players will put their listening skills, concentration and reflexes to the test. Equipment: A long rope or ribbon Lay the rope (or ribbon) on the ground in a spacious area, and get all the players to line up along it. Be sure there’s enough space either side for players to safely jump over the rope. Explain to the children that the side of the rope where they’re stood is the “bank” and the other is the “river”. When the game leader (this could be you or a designated person) calls the word “river”, the players must jump over the rope and “into the river”. When they call “bank” they must jump over the rope and back “onto the bank”. The game leader can call “river” or “bank” in any order, as many times as they wish! If a player jumps “into the river” or “onto the bank” when they are not supposed to, they are out of the game.