Vol 33-4 Winter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roach and Barker Are Elected President, Vice-President Of

VOLUME XLV VIRGINIA MILITARY INSTITUTE, LEXINGTON, VIRGINIA, JANUARY 17, 1955 NUMBER 14 Eugene List^ Famous Pianist Two '53 Grads Roach And Barker Are Elected To Concertize In Lexington To Be Air Tacs Two 1953 graduates of Virginia President, Vice-President Of OGA For Rockbridge Concert Series Military Institute have been select- ed for duty on the tactical staff Last Tuesday evening, immediately following the Corps One of the most widely Itnown' of the new Air Force Academy, Meeting, the Officer of the Guard Association met for the and praised of American pianists On Lee's Birthday according to an announcen\ent by is young Eugene List, who accord- purpose of electing new officers. Bill Maddox, the Retiring Colonel Robert M. Stillman, Air ing to international critical ac- Seven score to an added eight President, announced his decision to relinquish his position Force Academy Commandant. claim, is destined for music's per- Years bence, was upon this date, because of his desire to apply him- manent "Who's Who." He will ap- They are Lieutenants Harry C. A Virginian bom on the creat of self more diligently to his studies. pear here in concert on February Gornto, HI, of Norfolk, and Charles fate. Law Would Deepen "Basically, we hope to have the R. Steward, of Coolidge, Ariz., both 3 at Lexington High School unde^ The South has cause to same objectives as before: first of- of whom entered the Air Force the auspeces of the Rockbridge commemmrate. all, to enforce the Class System; pilot training program following Army Reserves Concert Series. -

Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957) Guy Mccoy

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 1-1957 Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957) Guy McCoy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation McCoy, Guy. "Volume 75, Number 01 (January 1957)." , (1957). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/79 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. • ••• BEST "tell then certainInlvy yvou want •a Progressive Series Plan teacher. us a story ... " I ke a career of private P~ogressive .Series te~~le~a:a excellent music backgrounds ~~~n~h:eya~~~~;l~~v~tm~ the high standa~s ref~~redto (an Ada Richter musical story, of course I) be eligible for an Appointment as a teu: er 0 e Progressive, Series Plan' of Music Education. piano beginners ••. why not a musical story? Yes. YOJ.lrchild deserves the best, he deserves a (like all children) love the magic of storyland. Bright Progressive Series Plan teacher. Every year more piano teachers turn to musical stories eyes grow brighter-interest reaches a new high at I h.ild receives the BEST to enhance their regular piano lessons. -

Mancillas and Tendler Ready for Gong

•tats Llbrsry. LAS VECAS IS THE MEMBER OF NATURAL GATEWAY TO THE ASSOCIATED PRESS THE COLORADO RIVER THE WORLD'S GREATEST BOULDER DAM PROJECT NEWS SERVICE 24TH. YEAR LAS VEOAS. NEVADA, TUESDAY SEPTEMBER 11, 1928 NUMBER 89 MAINEoc aoELECTIO OE ao N REPUBLICAIOI oc 30 N LANDSLIDE MANCILLAS AND TENDLER READY FOR GONG PROGRAM FOR TEACHERS WILL ALL READY FOR AMERICAN LEGION BE ENTERTAINED 79,000 MAJORITY FIGHT ARENA FRIDAY EVENING The regular welcoming recep BIG FIGHT CARD tion for the teachers will be held BREAKS RECORDS FIGHTS START AT 7:30 P. M. on the Court House lawn Friday evening at 7:30 o'clock. Joe Manciilas. Mexican Junior JOE MANCILLAS VS. K. O. LEW TENDLER In the past it has been the cus PORTLAND, Maine, Sept. 11 Lightweight Champion, arrived in 133 POUNDS—10 ROUNDS tom for the Mesquite Club and (AP)—By the Largest majority town yesterday vwih his manager WACO PLANE IS the Parent Teacher's Association BATHING BEAUTY ever given a gubernatorial candi George Ocien and siabiemate, Manciilas is undefeated. Tendler claims the Junior to each give some social affair date in Maine, William Tudor Charlie Rivers. Lightweight title of the Rock Mountain States. This for the teachers, but this year Gardiner, Republican, swept into Manciilas worked out before a WINNER IN thetwo organizations will cooperate CONTEST TODAY his democratic opponent Edward large crowd ol boxing lans and will be a sensational fight. We will have to string in giving a reception. tbe governorship yesterday over displayed enough to convince us with Manciilas—he has yet to lose a decision. -

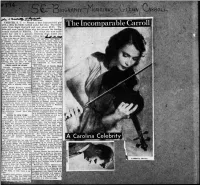

He Incomparable Carroll Came from Sears Roebuck and Cost About $2.50

QIOG-WHV ~nosic//w$ - (or * i SUSIE W. DOUGLAS CHESTER, S. C. Picture a tiny four-year-old girl with a little tin fiddle tucked under her chin. The fiddle he Incomparable Carroll came from Sears Roebuck and cost about $2.50. The little girl was Carroll Glenn who has become the leading woman violinist in America. The violin she now tucks under her chin is a genuine Cremona frojn which she draws the strains that make critics rave., This is the story of Carroll©s spec-1 tacular rise to fame. She was born The one she now uses bears a in Chester. South Carolina, of a parchment which reads: "This is to well known, well-to-do family, con certify that the violin sold this day sequently had no early struggles ex o Mrs. Carroll Glenn List is a cept thoss involved in learning that work of Joseph Guarn?rius del Gesu most difficult of instruments the of Cremona, it bears its original violin. No doubt tears rolled down abel dated 1743." No wonder Car- her pudgy cheeks, but her devoted roll guards it most carefully, tak- mother coaxed and encouraged her. ng it with her wherever she goes and saw that she had play time and placing it beside her chair. as w?ll as practice time. At the Musicians love thsir own instru age of six or seven she began les ments and will play upon no other. sons at the University of South The pianist. Arthur Rubenstetn, Carolina and was taken to and akes his piano by plane, but Car- rolls© instrument is more easily from Columbia for that purpose. -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

Chesterfield Put This Down Ac, Has Remained America’S Fastest'growing Cigarette; Over Two Billion Are Smoked Per Month

1---N /---- hililren. The unpn>tt ,d niovii Yukon Dell Yt. r.lierjfr, Alaska’s Tuner; irojector was in tin- middle of Hi* Hospital Ship now in .Juneau Phono .Juneau Music 49 ARE KILLED mil with inflanmiahU Him in uric Ready to Be Laid Up House or Hote l (last menu. —atlv. ) FAMOUS BATTLES ill a table. A caudle was hurtling ♦ ♦ ♦ WE WANT YOU TO KNOW I mil two lllms cauclil !:r< limn il TANW'A. Alaska, Sept. 7 Use the Classifieds. They pay. THAT WE SELL AND THEATRE FIRE rhere was a stillm then l In pn\eminent hospital lmat iMartlia \n for the :: ———-?!;:I trowd rushed fur llic ime dim ip line lias arrived here and wii INSTALL await orders ns to whether ii wii I I UMKRK’K, Ireland. Sept. 7- Forty ■ eo into winter hero or HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE nine prisons are reported to have quarters make other trips hefore the rive, ARCOLA -O- been killed and 10 injured in a fire in an movie theater. An SCHEDULE*FOR freeze-up. improvised By The Associated Press HEATING SYSTEMS unscreened projecting a p p a r a Mi s caught afire. One door, the onh Hauled exit, became jammed and many per- COAST LEAGUE (Garbage by J. J. WOODARD CO. Jim Jefferies knocked out Hob die (iraney, the referee, was all j sons were trampled to death and Month or Plumbing—Sheet Metal Work Fitzsimmons July 25, 11102, in the dressed up in the "conventional Opening Ibis afternoon, the clubs Trip j burned. Twenty nine bodies recov- General ; South Front Street eighth round of a bout in a vacant evening dress." if the Pacific Coast League will Contracting, Concrete ered are unrecognizable. -

Volume 64, Number 04 (April 1946) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1946 Volume 64, Number 04 (April 1946) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 64, Number 04 (April 1946)." , (1946). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/196 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIETRO MASCAGNI LAURITZ MELCHIOR, sensational Wag- nerian tenor of the Metropolitan Opera Company, recently celebrated his twen- tieth anniversary with the organization. To commemorate the occasion a gala concert was arranged, in which a num- ber of his colleagues joined Mr. Melchior in singing excerpts from three of the Wagner operas. Following the concert there was a back-stage ceremony, in which all departments of the Metropol- itan, from the board of directors to the stage hands, joined in paying tribute to the distinguished tenor. AN INTERNATIONAL music festival will take place in Prague, Czechoslovakia, from May 11 to 31, in commemoration of the fiftieth birthday of the Czech Phil- harmonic Orchestra. Leonard Bernstein, composer, conductor; Samuel Barber, composer; and Eugene List, pianist, will attend, representing the U.S. cured free upon request to the National THE RESTORED Co- and Inter-American Music Week Com- lonial city of Williams- BERNARD ROGERS’ mittee, 315 Fourth Avenue, New York 10. -

EASTMAN NOTES JUNE 2005 Draft: Web Date: July 5, 2005 INSIDE

NOTES JUNE 2005 A MAGAZINE FOR ALUMNI OF THE EASTMAN SCHOOL OF MUSIC FROM THE EDITOR Loss, love, and legacies Dear Eastman Alumni: More than any time since I began editing Eastman Notes, the winter and spring of 2004¬2005 was marked by a sense of loss, with the deaths of two inimitable NOTES figures in Eastman’s history: Frederick Fennell and Ruth Watanabe, who died in Volume 23, Number 2 December 2004 and February 2005 respectively. June 2005 It’s representative of their importance, not just to the School but to the musical world in general, that everyone reading this magazine, no matter when they at- Editor tended, knows who Frederick Fennell and Ruth Watanabe are. Both are indelibly David Raymond associated with two monuments of the School—the Wind Ensemble and the Sib- Assistant editor ley Library. Fennell built a new model for wind band playing—and a repertory— Juliet Grabowski pretty much from scratch; while Ruth Watanabe didn’t found the Sibley Library, Contributing writers she certainly developed it to its present eminence over a 40-year career. (See Martial Bednar Christine Corrado pages 6 and 8 for more Susan Hawkshaw on their remarkable ca- Contributing photographers reers.) Both continued Richard Baker to be generous with Kurt Brownell their time and talent Bob Klein well after retirement— Gelfand-Piper Photography Amy Vetter Fennell visiting Eastman numerous times to con- Photography coordinators Nathan Martel duct, Watanabe as the Amy Vetter School’s historian. Design These two people were Steve Boerner Typography & Design definitely respected as professionals, but they Frederick Fennell Ruth Watanabe Published twice a year by the Office of were also loved as people— Communications, Eastman School of Music, 26 Gibbs Street, Rochester, NY, see the brief tributes to Fennell by his successors Don Hunsberger and Mark 14604, (585) 274-1050. -

Download Finding

National Federation of Music Clubs Records This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit April 05, 2018 Describing Archives: A Content Standard National Federation of Music Clubs Indianapolis, Indiana National Federation of Music Clubs Records Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 5 History and Governance.......................................................................................................................... 5 Proceedings, Minutes, Reports, Programs.............................................................................................17 Financial/Legal/Administrative..............................................................................................................34 NFMC Publications............................................................................................................................... 59 Presidential papers................................................................................................................................. 78 Activities/Projects/Programs..................................................................................................................82 Scrapbooks.......................................................................................................................................... -

Inside and Outside Joshua Harry George Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2012 Inside and outside Joshua Harry George Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Fine Arts Commons Recommended Citation George, Joshua Harry, "Inside and outside" (2012). LSU Master's Theses. 1647. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/1647 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INSIDE AND OUTSIDE A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and College of Arts and Design in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in The School of Art by Joshua Harry George B.F.A. University of Kansas, 2009 May, 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I’d like to thank Coach Dave Pichon of the 14th Street Gym in Baton Rouge, LA. From the very 1st time I met him, he was excited about my goals, and he was very welcoming. I also want to express thanks to Gary Riley, Chris Pham, and Corey Dyer for reaching out to me as much as they have. These are young men that share a passion for boxing, and they’ve also supported me from my very 1st visit to the gym. I’d also like to thank Coach Tafari Beard from Sports Academy in Baton Rouge, LA as well as the boxers of that gym. -

Ring Magazine

The Boxing Collector’s Index Book By Mike DeLisa ●Boxing Magazine Checklist & Cover Guide ●Boxing Films ●Boxing Cards ●Record Books BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INSERT INTRODUCTION Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 2 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK INDEX MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS Ring Magazine Boxing Illustrated-Wrestling News, Boxing Illustrated Ringside News; Boxing Illustrated; International Boxing Digest; Boxing Digest Boxing News (USA) The Arena The Ring Magazine Hank Kaplan’s Boxing Digest Fight game Flash Bang Marie Waxman’s Fight Facts Boxing Kayo Magazine World Boxing World Champion RECORD BOOKS Comments, Critiques, or Questions -- write to [email protected] 3 BOXING COLLECTOR'S INDEX BOOK RING MAGAZINE [ ] Nov Sammy Mandell [ ] Dec Frankie Jerome 1924 [ ] Jan Jack Bernstein [ ] Feb Joe Scoppotune [ ] Mar Carl Duane [ ] Apr Bobby Wolgast [ ] May Abe Goldstein [ ] Jun Jack Delaney [ ] Jul Sid Terris [ ] Aug Fistic Stars of J. Bronson & L.Brown [ ] Sep Tony Vaccarelli [ ] Oct Young Stribling & Parents [ ] Nov Ad Stone [ ] Dec Sid Barbarian 1925 [ ] Jan T. Gibbons and Sammy Mandell [ ] Feb Corp. Izzy Schwartz [ ] Mar Babe Herman [ ] Apr Harry Felix [ ] May Charley Phil Rosenberg [ ] Jun Tom Gibbons, Gene Tunney [ ] Jul Weinert, Wells, Walker, Greb [ ] Aug Jimmy Goodrich [ ] Sep Solly Seeman [ ] Oct Ruby Goldstein [ ] Nov Mayor Jimmy Walker 1922 [ ] Dec Tommy Milligan & Frank Moody [ ] Feb Vol. 1 #1 Tex Rickard & Lord Lonsdale [ ] Mar McAuliffe, Dempsey & Non Pareil 1926 Dempsey [ ] Jan -

An Analysis and Performance Guide to Benjamin Lees's Odyssey I and II / by Youmee

AN ANALYSIS AND PERFORMANCE GUIDE TO BENJAMIN LEES’S ODYSSEY I AND II D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for The Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Youmee Kim * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Document Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Glaser, Advisor Dr. Patrick Woliver ________________ Advisor Dr. Mellasenah Morris Graduate Program in Music Copyright by Youmee Kim 2008 ABSTRACT This document provides analyses and performance guidelines for Benjamin Lees’ Odyssey I (1970) and II (1986). This paper also discusses the composer’s biographical background and musical style. I will identify in particular the similarity between art and music from a surrealistic perspective. This document contains five chapters: Chapter 1, Introduction; Chapter 2, biography of Benjamin Lees and surrealism; Chapter 3, style analyses of Lees’s Odyssey I and II ; Chapter 4, performance guidelines for Odyssey I and II ; Chapter 5, conclusion. Musical examples are included and the email correspondence from the composer, the catalogue of Lees’ piano music and the discography are provided in the Appendix. ii Dedicated to my mom in Heaven iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor, Professor Steven M. Glaser of the Ohio State University, for his guidance and sincere support throughout the entire process of writing this document. Without his valuable suggestions and advice, this paper would not have been possible. I am blessed to have met Dr. Patrick Woliver, who served on my D.M.A. committee throughout my four recitals and candidacy examination.