Farming Systems of the Syrian Arab Republic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

Syrian Arab Republic

Syrian Arab Republic News Focus: Syria https://news.un.org/en/focus/syria Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria (OSES) https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/ Syrian Civil Society Voices: A Critical Part of the Political Process (In: Politically Speaking, 29 June 2021): https://bit.ly/3dYGqko Syria: a 10-year crisis in 10 figures (OCHA, 12 March 2021): https://www.unocha.org/story/syria-10-year-crisis-10-figures Secretary-General announces appointments to Independent Senior Advisory Panel on Syria Humanitarian Deconfliction System (SG/SM/20548, 21 January 2021): https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sgsm20548.doc.htm Secretary-General establishes board to investigate events in North-West Syria since signing of Russian Federation-Turkey Memorandum on Idlib (SG/SM/19685, 1 August 2019): https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sgsm19685.doc.htm Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels V Conference, 29-30 March 2021 https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2021/03/29-30/ Supporting the future of Syria and the region - Brussels IV Conference, 30 June 2020: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2020/06/30/ Third Brussels conference “Supporting the future of Syria and the region”, 12-14 March 2019: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2019/03/12-14/ Second Brussels Conference "Supporting the future of Syria and the region", 24-25 April 2018: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/meetings/international-ministerial-meetings/2018/04/24-25/ -

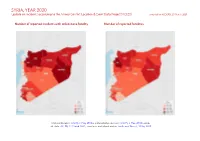

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021

SYRIA, YEAR 2020: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 25 March 2021 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, 6 May 2018a; administrative divisions: GADM, 6 May 2018b; incid- ent data: ACLED, 12 March 2021; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 6187 930 2751 violence Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 2 Battles 2465 1111 4206 Strategic developments 1517 2 2 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 1389 760 997 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 449 2 4 Riots 55 4 15 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 12062 2809 7975 Disclaimer 9 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). Development of conflict incidents from 2017 to 2020 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 12 March 2021). 2 SYRIA, YEAR 2020: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 25 MARCH 2021 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic

United Nations S/2016/534 Security Council Distr.: General 16 June 2016 English Original: Arabic Identical letters dated 13 June 2016 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council On instructions from my Government, I should like to draw your attention to the following information regarding terrorist acts committed by armed terrorist groups active in Syrian territory during the month of May 2016: 3 May • Some 19 people were killed and more than 65 others were injured, including women and children, when armed terrorist groups fired dozens of shells at Dubayt Hospital and other neighbourhoods in the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • A civilian was killed when a mortar shell landed in Khan al-Shaykh in Rif Dimashq. • A mortar shell landed in Dar‘a, injuring a civilian. • A mortar shell landed in the Tahtuh neighbourhood in Dayr al-Zawr, injuring a civilian. 4 May • Four civilians were killed and more than 15 others were injured, including women and children, when dozens of shells fell in several neighbourhoods of the city of Aleppo and its countryside. • The terrorist Nusrah Front organization perpetrated a massacre in the village of Khuwayn in Idlib, killing 15 civilians, including four children. 5 and 6 May • On Thursday, 12 civilians were killed and 40 injured when terrorist explosions occurred in the city of Upper Mukharram in the Homs countryside. • Terrorist groups fired several shells at the Maydan neighbourhood in Aleppo, killing one civilian and injuring another. Material damage was caused. -

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Quelques Plantes Présentes En Mésopotamie1 Anne-Isabelle Langlois2

Le Journal des Médecines Cunéiformes n° 18, 2011 Quelques plantes présentes en Mésopotamie1 Anne-Isabelle Langlois2 Je remercie Gilles Buisson et Annie Attia d'avoir attiré mon attention sur l'utilité pour la communauté scientifique de pouvoir accéder à une liste des plantes retrouvées par les fouilles archéologiques effectuées en Iraq et en Syrie. En me basant sur la précieuse bibliographie archéobotanique des sites du Proche-Orient élaborée par Naomi F. Miller et mise en ligne sur le site http://www.sas.upenn.edu/~nmiller0/biblio.html, j'ai examiné les rapports des différentes fouilles afin d'établir la liste suivante. Cette liste, qui ne se veut pas exhaustive, présente les plantes, selon leur nom latin et par ordre alphabétique, retrouvées lors de fouilles au Proche-Orient. Leur nom anglais, parfois, et la famille à laquelle elles appartiennent selon la classification classique des plantes sont précisés entre parenthèses. Chaque nom de plante est alors suivi par l'inventaire des sites archéologiques, eux- mêmes classés par ordre alphabétique, attestant sa présence. Abutilon theophrasti (Malvaceae) : Cafer Höyük Acer (Maple, Aceraceae) : Khirbet al Umbashi, M'lefaat, Tell al-Rawda Achillea (Asteraceae) : Umm el-Marra Adonis aestivalis (Ranunculaceae) : Cafer Höyük Adonis dentata (Ranunculaceae) : Nimrud, Tell Aswad Adonis flammea type (Ranunculaceae) : M'lefaat, Tell Nebi Mend Adonis cf. annua (Ranunculaceae) : Abu Hureyra, Tell Nebi Mend Adonis sp.3 (Pheasant's eye, Ranunculaceae) : Dja'de, Emar, Jerf el Ahmar, Qatna, Tell Bderi, Tell Halula, Tell Jerablus, Tell Jouweif, Tell Leilan, Tell Mozan, Tell Mureybet, Tell Qara Qūzāq, Tell al- Rawda, Tell Sheikh Hamad, Umm el-Marra Aegilops crassa (Goat's-face grass, Gramineae/Poaceae) : Cafer Höyük, Choga Mami, Nimrud, Tell Brak, Tell Jerablus, Tell Karrana, Tell Qara Qūzāq, Umm Qseir 1 Note des éditeurs : article reçu en décembre 2010. -

Syria Crisis

Syria 0146/Noorani 0146/Noorani Crisis - Monthly humanitarian situation report © UNICEF/NYHQ2014 © 18 MARCH – 17 APRIL 2014: SYRIA, JORDAN, LEBANON, IRAQ, TURKEY AND EGYPT SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights In Syria • During the reporting period, UNICEF participated in four inter-agency convoys in Syria, reaching 2,800 families in Douma, in Rural Damascus; 3,500 families 4,299,600 in Sarmada and 4,000 families in Saraqib in Idleb; as well as 3,000 families in #of children affected Termalleh and 1,000 in Al Ghanto, in Homs. 9,347,000 • The UNICEF-led WASH Sector organized a nationwide workshop from 7-9 # 0f people affected April in Damascus bringing together 150 participants from across the (SHARP 2014) country. During the reporting period, UNICEF and ICRC provided chlorine supplies for the purification of public water supplies, benefitting Outside Syria approximately 16.9 million people. 1,379,986 • On 30 March, Ministry of Health of Iraq declared the first polio outbreak in #of registered refugee children and the country since 2000. UNICEF continues to support the on-going polio children awaiting registration campaigns for all children under 5, with the most recent campaign having been held 6-10 April with preliminary results showing 5.2 million children 2,700,560 vaccinated. # of registered refugees and persons awaiting registration • Preliminary results from the April polio vaccination campaign in Syria show (17 April 2014) an estimated 2.9 million children reached. A round of vaccinations was also undertaken in Lebanon in April with results pending. Syria Appeal 2014* • UNICEF has supported 61,490 children (including 17,957 vulnerable Lebanese children) to enrol in public schools, with over 139,000 children supported by US$ 222.19 million the sector. -

Exhibition Checklist I. Creating Palmyra's Legacy

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1. Caravan en route to Palmyra, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799. Proof-plate etching. 15.5 x 27.3 in. (29.2 x 39.5 cm). The Getty Research Institute, 840011 I. CREATING PALMYRA'S LEGACY Louis-François Cassas Artist and Architect 2. Colonnade Street with Temple of Bel in background, Georges Malbeste and Robert Daudet after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 16.9 x 36.6 in. (43 x 93 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 58. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 1 3. Architectural ornament from Palmyra tomb, Jean-Baptiste Réville and M. A. Benoist after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 18.3 x 11.8 in. (28.5 x 45 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 137. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 4. Louis-François Cassas sketching outside of Homs before his journey to Palmyra (detail), Simon-Charles Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 20. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 5. Louis-François Cassas presenting gifts to Bedouin sheikhs, Simon Charles-Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41 cm). -

A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2015 A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's Euphrates Valley Expedition Metal Collection Jamie Patrick Henry University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons, Islamic World and Near East History Commons, and the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Henry, Jamie Patrick, "A Preliminary Museological Analysis of the Milwaukee Public Museum's Euphrates Valley Expedition Metal Collection" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 1054. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1054 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A PRELIMINARY MUSEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S EUPHRATES VALLEY EXPEDITION METAL COLLECTION by Jamie Patrick Henry A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Anthropology at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2015 ABSTRACT A PRELIMINARY MUSEOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF THE MILWAUKEE PUBLIC MUSEUM’S EUPHRATES VALLEY EXPEDITION METAL COLLECTION by Jamie Patrick Henry The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2015 Under the Supervision of Professor Bettina Arnold Destruction of ancient sites along the Euphrates River in northern Syria due to the construction of the Tabqa Dam and the formation of Lake Assad led to many international salvage expeditions, including those conducted between 1974 and 1978 by the Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) at the site of Tell Hadidi, Syria under the direction of Dr. -

The Euphrates River: an Analysis of a Shared River System in the Middle East

/?2S THE EUPHRATES RIVER: AN ANALYSIS OF A SHARED RIVER SYSTEM IN THE MIDDLE EAST by ARNON MEDZINI THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SCHOOL OF ORIENTAL AND AFRICAN STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF LONDON September 1994 ProQuest Number: 11010336 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010336 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract In a world where the amount of resources is constant and unchanging but where their use and exploitation is growing because of the rapid population growth, a rise in standards of living and the development of industrialization, the resource of water has become a critical issue in the foreign relations between different states. As a result of this many research scholars claim that, today, we are facing the beginning of the "Geopolitical era of water". The danger of conflict of water is especially severe in the Middle East which is characterized by the low level of precipitation and high temperatures. The Middle Eastern countries have been involved in a constant state of political tension and the gap between the growing number of inhabitants and the fixed supply of water and land has been a factor in contributing to this tension.