A Second Container Port for Melbourne? Build It in the West for 2036

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Victoria Harbour Docklands Conservation Management

VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT PLAN VICTORIA HARBOUR DOCKLANDS Conservation Management Plan Prepared for Places Victoria & City of Melbourne June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS xi PROJECT TEAM xii 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background and brief 1 1.2 Melbourne Docklands 1 1.3 Master planning & development 2 1.4 Heritage status 2 1.5 Location 2 1.6 Methodology 2 1.7 Report content 4 1.7.1 Management and development 4 1.7.2 Background and contextual history 4 1.7.3 Physical survey and analysis 4 1.7.4 Heritage significance 4 1.7.5 Conservation policy and strategy 5 1.8 Sources 5 1.9 Historic images and documents 5 2.0 MANAGEMENT 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Management responsibilities 7 2.2.1 Management history 7 2.2.2 Current management arrangements 7 2.3 Heritage controls 10 2.3.1 Victorian Heritage Register 10 2.3.2 Victorian Heritage Inventory 10 2.3.3 Melbourne Planning Scheme 12 2.3.4 National Trust of Australia (Victoria) 12 2.4 Heritage approvals & statutory obligations 12 2.4.1 Where permits are required 12 2.4.2 Permit exemptions and minor works 12 2.4.3 Heritage Victoria permit process and requirements 13 2.4.4 Heritage impacts 14 2.4.5 Project planning and timing 14 2.4.6 Appeals 15 LOVELL CHEN i 3.0 HISTORY 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Pre-contact history 17 3.3 Early European occupation 17 3.4 Early Melbourne shipping and port activity 18 3.5 Railways development and expansion 20 3.6 Victoria Dock 21 3.6.1 Planning the dock 21 3.6.2 Constructing the dock 22 3.6.3 West Melbourne Dock opens -

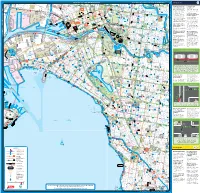

On the Road on the Paths

On the road Hospice DLEY PARK EN E Is it legal to ride E H M DA NOLA N AV RA two abreast? ER Xavier D T Prep Are the road rules the S 3101 BVD LM Coll. Yes, but you must not ride 9 Hole Par 3 ST C KEW R same when you’re on a WA A 3101 GOLF COURSE C K YARRA McEVOY ST KEVIN SYLVA ST C more than 1.5 metres apart. TANTON GV bike or driving a car? SEE ADJOINING CITY OFYARR YARRA & BOROONDARA TRAVELSMART MAPS BAN N LA ST ST HO S BVD ST GIPP W.H.S. MA V YARRA BEND PARK RAVEN ST YTON i ST ST I Dickinson PHY H T T T C R ST YARRA T GV Yes, bicycles are classified und S Res E E E S S GIPPS S ST ST T R Is it OK to occupy a ST ST ST T r Sch O T M L L O E RD ST S S HODGSO MUR 16 R REEVES L D D E E M S 350 p OU LL T PEEL ST GLASSH I as vehicles under the law L H E D D A e S AEL ST CT ST RY whole traffic lane when Steine C S ST 684 A D LAVER ST O O . STEVENSON Sophia ST T RAVE ST S ST O PH D Yarra ST W S ST EL IT ST CR R R ROBERT ST MOLLISON FIN ST Ste H 246 (H (H L ST A HEN LIT. -

Download Full Article 2.9MB .Pdf File

June 1946 MEM. NAT. Mus. V1cT., 14, PT. 2, 1946. https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1946.14.06 THE SUNKLANDS OF PORT PHILLIP BAY AND BASS STRAIT By R. A. Keble, F.G.S., Palaeontologist, National Jiiiseurn of Victoria. Figs. 1-16. (Received for publication 18th l\fay, 1945) The floors of Port Phillip Bay and Bass Strait were formerly portions of a continuous land surface joining Victoria with Tasmania. This land surface was drained by a river system of which the Riv-er Y arra was part, and was intersected by two orogenic ridges, the Bassian and King Island ridges, near its eastern and western margins respectively. \Vith progressive subsidence and eustatic adjustment, these ridges became land bridges and the main route for the migration of the flora and fauna. At present, their former trend is indicated by the chains of islands in Bass Strait and the shallower portions of the Strait. The history of the development of the River Yarra is largely that of the former land surface and the King Island land bridge, and is the main theme for this discussion. The Yarra River was developed, for the most part, during the Pleistocene or Ice Age. In Tasmania, there is direct evidence of the Ice Age in the form of U-shaped valleys, raised beaches, strandlines, and river terraces, but in Victoria the effects of glaciation are less apparent. A correlation of the Victorian with the Tasmanian deposits and land forms, and, incidentally, with the European and American, can only be obtained by ascertaining the conditions of sedimentation and accumulation of such deposits in Victoria, as can be seen at the surface1 or as have been revealed by bores, particularly those on the N epean Peninsula; by observing the succession of river terraces along the Maribyrnong River; and by reconstructing the floor of Port Phillip Bay, King Bay, and Bass Strait, and interpreting the submerged land forms revealed by the bathymetrical contours. -

Infrastructure Victoria Second Container Port Advice

Infrastructure Victoria Second Container Port Advice Port Strategic Transport Modelling Final | 2.5 4 April 2017 Todd Road / Cook Street / Webb Dock Drive / Westgate Freeway Port Strategic Transport Modelling Infrastructure Victoria Second Container Port Advice Project No: IS175000 Document Title: Port Strategic Transport Modelling Document No.: Final Revision: V2.5 Date: 4 April 2017 Client Name: Client No: Project Manager: John Richardson Author: John Richardson File Name: J:\IE\Projects\03_Southern\IS175000\06 Technical\IV Ports Advice VITM Modelling Report V2.5.docx Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited ABN 37 001 024 095 Floor 11, 452 Flinders Street Melbourne VIC 3000 PO Box 312, Flinders Lane Melbourne VIC 8009 Australia T +61 3 8668 3000 F +61 3 8668 3001 www.jacobs.com © Copyright 2017 Jacobs Group (Australia) Pty Limited. The concepts and information contained in this document are the property of Jacobs. Use or copying of this document in whole or in part without the written permission of Jacobs constitutes an infringement of copyright. Limitation: This report has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Jacobs’ Client, and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between Jacobs and the Client. Jacobs accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this report by any third party. Document history and status Revision Date Description By Review Approved 1 31/01/2017 Limited to a list of model inputs for the purpose of J Richardson confirming all inputs. 2 10/03/2017 Modelling outputs added J Richardson A Newman 3 27/03/2017 Updated with Deloitte comments J Richardson A Newman 4 04/04/2017 Updated with IV comments J Richardson A Newman i Port Strategic Transport Modelling Contents 1. -

UNLEASHING the POTENTIAL of NATURE DISCUSSION PAPER on CITY ECOLOGY, ECOSYSTEMS and BIODIVERSITY Join the Discussion Online at Participate.Melbourne.Vic.Gov.Au/Nature

UNLEASHING THE POTENTIAL OF NATURE DISCUSSION PAPER ON CITY ECOLOGY, ECOSYSTEMS AND BIODIVERSITY Join the discussion online at participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/nature Acknowledgements Many people have contributed ideas presented within this Discussion Paper including within the City of Melbourne, and researchers at the Australian Research Centre for Urban Ecology (ARCUE), RMIT, University of Melbourne and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. Cover image of Blue Banded Bee, Amegilla bee Source: Museum Victoria participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/nature CONTENTS Purpose and process 03 Key terms 04 Chapter 1: Nature in Melbourne 05 Chapter 2: How does our city contribute to the Australian landscape? 09 Chapter 3: Why should we care about urban ecosystems? 11 Chapter 4: How can we better value and manage nature? 15 Chapter 5: How can we undertake nature sensitive urban design and planning? 17 Chapter 6: Should we increase nature in the private realm? 21 Chapter 7: What symbolises nature for Melburnians? 23 Chapter 8: How can ecology help us respond to climate change? 28 Chapter 9: How can Melbourne demonstrate leadership? 31 Selected resources 33 References 34 2 participate.melbourne.vic.gov.au/nature Purpose and process Purpose Process The purpose of this discussion paper is to An indicative timeline for the process support conversation and seek comment is shown below: from our community and stakeholders to contribute to the development of a strategic policy framework for municipal ecology, biodiversity and ecosystem services, or nature within our city. February 2015 City of Melbourne has not previously Discussion paper released for public comment. formulated a comprehensive policy position on urban nature. -

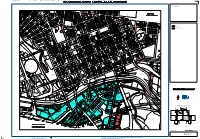

Melbourne Metro Rail Project 20 April 2016 Revision: C1 MMR-AJM-PWAA-RP-NN-000815 Reference: CMS332569

Melbourne Metro Rail Project 20 April 2016 Revision: C1 MMR-AJM-PWAA-RP-NN-000815 Reference: CMS332569 Transport Impact Assessment Melbourne Metro Rail Authority Document control record 121 Exhibition Street Melbourne VIC 3000 PO Box 23061 Docklands VIC 8012 Australia A person using AJM JV documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by AJM JV. Document control Report title Transport Impact Assessment Document ID MMR-AJM-PWAA-RP-NN-000815 Contract No. CMS332569 File path Client Melbourne Metro Rail Authority Client contact Daniel Cullen Revision Rev Date Prepared by Author/s Verifier Approver details/status Peter Hunkin Final issued for David C1 20/04/2016 Peter Hunkin & Katherine Lisa Ryan Exhibition Anderson Mitchell Current revision C1 Approval Approver Author signature signature Name Peter Hunkin Name Lisa Ryan © Copyright 2016 AJM Joint Venture. The concepts, data and information contained in this document are the property of AJM Joint Venture. No part of this document may be reproduced, used, copied, published or adapted for use except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 or with the consent of AJM Joint Venture. This report has been prepared on behalf of, and for the exclusive use of Melbourne Metro Rail Authority (“MMRA”), and is subject to, and issued in accordance with, the provisions of the contract between AJM Joint Venture and MMRA. AJM Joint Venture makes no representations and undertakes no duty to any third party who may use or rely upon this report, and accepts no liability or responsibility whatsoever for, or in respect of, any use of, or reliance upon, this report by any third party. -

Ocklandsstrategy

OCKLANDSSTRATEGY 711.5 099451 DOC strategy Reference map overleaf ELBUURNE DOCKLANDS: STRATEGY FOR REDEVELOPMENT DOCKLANDS TASK FORCE JUNE 1992 •0) 0> 'tl .... • 0) U 0) 1:1 "is -g :>- o~ Reference map o~ ... §~ [-< p.. ;:::10) ~ \ o ;::l E-<E-<~ victoria Street '" ~ortn Dynon Road ... To Foots-1-----cray ., ,. ., ,.. DoCkraUhne ~-bb ,- - • Existing road and rail network • Proposed road and rail network • Docklands 1 Spencer Street Station 2 Former Railways Administration Building 3 World Congress Centre 4 World Trade Centre 5 Museum of Victoria 6 Charles Grimes Bridge 7 Flagstaff Gardens 8 Flagstaff Station 9 North Melbourne Station 250 500 750 1000 scale of metres 11Ii\fl~ lilllllll~11 ~I~ ~11111~1\~li lili\~\ M0052705 Melbourne Docklands: Strategy for Redevelopment A guide to redevelopment of Docklands, providing a broad framework within which further detailed planning and design and, ultimately, development can be undertaken. Docklands Task Force June 1992 Infrastructure Library 711.5 8489276 099451 Melbourne docklands : DOC strategy strategy for redevelopment CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 3 4.3.3.2 The internal road network 52 1.1 THE SITE 5 4.3.3.3 Traffic impacts 56 1.2 BRIEF HISTORY 5 4.3.4 Webb Dock rail line 57 1.3 STATE GOVERNMENT 4.3.5 Cars and parking 58 OBJECTIVES 6 4.3.6 Water transport 58 1.4 DOCKLANDSTASKFORCE 6 4.4 ECONOMIC 1~5 PUBLIC CONSULTATION 7 DEVELOPMENT 59· 1.6 DOCKLANDS AUTHORITY 7 4.4.1 Entertainment, leisure and 2 THE VISION 9 tourism 60 3 EXISTING 4.4.2 Transport 60 CHARACTERISTICS 17 4.4.3 Telecommunications 60 -

Z O N E S MAP No 8

ST LT.ERROL PL PL CAPEL ST DRYBURGH ST PL MAGENTA LIT LOTHIAN ST ST PL LIT. RAGLAN LA LT HOWARD ST GARDINER MM EE LL BB OO UU RR NN EE PP LL AA NN NN II NN GG SS CC HH EE MM EE -LITTLE- CARDIGAN LL OO CC AA LL PP RR OO VV II SS II OO NN WARWICK MM EE LL BB OO UU RR NN EE PP LL AA NN NN II NN GG SS CC HH EE MM EE -- LL OO CC AA LL PP RR OO VV II SS II OO NN ST MELBOURNE EXHIBITION BUILDING ST LOTHIAN ST MISSION ERROL CURZON ST QUEENSBERRY LEVESON PL HOWARD PL CURZON BLAIRS TRAFALGAR LEVESON PL MOSS LT. COBDEN CORNELL ST LT. PL LA ERROL LANSDOWNE ST VICTORIA LITTLE PRINCESS PL PL ST st PL GRACIE LA ST IEVERS PL QUEENSBURY CHETWYND Z O N E S st VICTORIA PL CARLTON PL KING HOWARD ST HUDSON ST ALMA DRYBURGH PL GARDENS LOTHIAN ABBOTSFORD Pond CAPEL ESSEX PEEL SPENCER BOUVERIE PL EARL ELM TREE COBDEN TCE CARDIGAN ST LYGON ST LEICESTER BOUVERIE ST ST SWANSTON NICHOLSON DRUMMOND MILLER RATHDOWNE ST PL CARDIGAN EADES St. Mary's SPENCER ALLISON MILLER R.C. Church LA ST ST VICTORIA ST PL ST SAN ST ST ST KING West ST ST Melbourne ST ST ST ST State MARCO TCE ST WILLIAM School CARDIGAN ST LA ST ORR PL ST Melbourne Pond SPENCER CARDIGAN SWANSTON Trades Hall SS ee ee YY AA RR RR AA LYGON SS ee ee YY AA RR RR AA PL SS ee ee YY AA RR RR AA ST TRADESHALL DRUMMOND ST CARLTON PL ST STANLEY RATHDOWNE ZEPLIN VICTORIA GARDENS PP LL AA NN NN II NN GG SS CC HH EE MM EE HOWARD VICTORIA EMILY VICTORIAN HORT. -

Docklands and Major Projects Committee Report

Page 1 of 5 DOCKLANDS AND MAJOR PROJECTS Agenda Item 5.6 COMMITTEE REPORT 7 August 2007 WEBB DOCK RAIL LINK Division Sustainability & Regulatory Services Presenter Geoff Lawler, Director Sustainability & Regulatory Services Purpose 1. To advise the Committee on planning for the reinstatement of the Webb Dock railway line. Recommendation from Management 2. The Docklands and Major Projects Committee resolve that: 2.1. the City of Melbourne host a public information meeting on the Webb Dock Rail Link Environment Report, once it is released by the Port of Melbourne Corporation, to ensure that stakeholders are well informed of the technical issues associated with the proposal. Key Issues 3. The Victorian Government has established a process to consider a proposal by the Port of Melbourne Corporation to reinstate the rail line from the Dynon Rail Terminal through to Webb Dock, which was discontinued in 1996. 4. Webb Dock is mainly used currently for roll-on/roll-off freight between Melbourne and Tasmania, and the import and export of cars. It is the only major terminal in the Port that does not have direct rail access. The Port of Melbourne Corporation’s draft Port Development Plan envisages that Webb Dock will be developed from 2015-2035 to handle 50% of the Port’s international container trade and to be the major terminal for Bass Strait/Coastal freight. It is unlikely that this could happen without reinstatement of a rail option. 5. To avoid the congestion in inner Melbourne that would eventuate from not doing so, long-standing Council policy has been to support the reinstatement of the rail line, on the alignment currently under consideration (i.e. -

Jmmv1914501.Pdf

Memoirs of the National Museum, Melbourne July 1914 https://doi.org/10.24199/j.mmv.1914.5.01 ON THE SUCCESSION AND HOMOTAXIAL RELATIONSHIPS OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAINOZOIC SYSTEM. By Frederick Chapman, A.L.8., F.R.lll.8., Palccontologist to the N :itional 111 usewn, Jf elbourne. CONTENTS. l'.\llE Previous Opinions of Time Equivalents . 5 The Relative Values of the Percentage l\Tcthod; and the Uomparison of Typical Faunas, in determining the Ages of the Austrnlian Cainozoic Strata . 10 Some Cosmopolitan and Widely-distributed Fossil Types and their Significance . 13 On the Absence o( Nununnlites in the Cainozotcs of ::,outhem Austrnli11. 20 The Evidence of the Complex-strnctured Foraminif era in the Australian Cainozoic System . 23 8tratigraphical Notes bearing on the Sequence of the Strata 2G 'l'able o{ Cainozoic Rtrat.a in Australia : 50 Summary of Conclw1ion1:1 50 PREVIOUS OPINIONS OF TIME EQUIVALENTS. In the earlier day::; of palrnontological work in Victoria, the conclusions as to the age of the rich Tertiary faunas of southern Australia* were necessarily founded on limited evidence, derived from an imperfectly-known series of fosf3ils. The palmontology of these beds had then been scarcely touched by systematic worker::;, so that the small number of specie:-: available for purposes of com parison. both in relation to the question of local stratigraphical sequence and the wider one of correlating them with the well-studied Tertiary fauna:-; of Europe, rendered a solution of the probk'm one of great difficulty. The first effort at correlation was ma.de by Sir A. R. C. Selwyn in 18/54, who, in a "Report on the Geology, Palreontology, and }lineralogy of the Country situated between Melbourne, ,Vestern rort Bay, Cape Schanck, and Point Nepcan, "t :-:;tatecl, "Both the clay and limestone" [ of the l\fornington beds= Balcombian] :: arc very rich in fossil remains, and both in general lithological character, * By southern Australi:t it is intended to include the State� of South Australia n.ml Victoria. -

The Graptolite-Bearing Rocks of Victoria, Australia

T. S. Hall—Graptolite Rocks, Victoria, Australia. 439 II.—THE GRAPTOLITE-BEARING ROOKS OF VICTORIA, AUSTRALIA. By T. S. HALL, M.A., Melbourne University. (PLATE XXII.) INTRODUCTION. rriHE area occupied by Lower Palasozoic rocks in Victoria is an 1_ extensive one, and is pretty equally divided between Ordovician and Silurian, the part occupied by Cambrian being small. According to Dr. A. R. C. Selwyn, formerly Director of the Geological Survey of the Colony, the total area amounts to somewhere about 30,000 square miles in extent,1 and although in this estimate he included all areas occupied by these rocks provided the cover was not more than .'350 feet in thickness, it will still leave us with a large extent of country over which graptolites may be found. The earliest record of the occurrence of these fossils in Victoria is on a map of Selwyn's published in 1856, where it is Btated in a note that graptolites were found for the first time in Australia by C. D. H. Aplin in May, 1856, at a locality indicated on the Saltwater River near Keilor, about ten miles north-west of Melbourne. No identi- fications have ever been made from these beds, which yield a few species of Monograptida3 in a poor state of preservation. Very shortly after this graptolites were found in the Lower Ordovician rocks of Bendigo. In an essay contributed to the Catalogue of the Victorian Exhibition of 1861, Professor McCoy recorded from various localities several species which included Diplograptidae, Dichograptidae, and Dicranograptidse, as well as Monograptus ludensis, which showed that even thus early almost the whole range of graptolite-bearing rocks had been examined. -

To View Asset

4 ~ 18. nJ I :11 I I I INTERIM REPORT I BY I' ~~I. , t- . V\ INVESTIGATION.' COMMITTEE I ~ .,.. I FOH • I GOVERJ\1J;H<:NT PROJECTS IN THE I PORT OF :rvlELBODRNE/SODTH 'MELB01JRNE AREA I I I I I I I I . I ....-'-----------...--:---~ X 711. 4099 62210~71 C}:::.a.trr!'1F.tl"i : ,I: 45J DOC: Interim;report by Investigation Committee .J. R. Ashworth for' Government Projects Ex.cell tive Director in·the Port 'of Melbourne Public Works Department . ~-Ir I So~!.h·¥~lb?urne f.re~ 30th October, 1~75. ____ ~ ____~_~ __ ._ .. _.c.._ . ./ . ~ .. I CONTENTS I I 1 • PREANBLE I 2. TERMS OF REFERENCE I 3. , 'HEHBERSHIP HEETINGS AND PROCEDURES I 4 ~ l}-1eetings I 4.2 Sub-Committees 4.3 Sources and Pres~ntation of Information to the Committee II 5. SALIE1'\T ISSUES I 5.1 N.H.T. Commissioners proposed develupment pl~n 5.2 '''est Gate Bridge Approaches I 5.3 Johnson Stree,t Bridge Approaches, 5.4 ~ropo5ed ,{orld Trade Centre " 'I 5.5 Residential Areas and Developments I 6 . PORT OF NELBOURNE DEVELOPMENT I 6.1 Ba.ckground 6,.2' Trade Forecasts I 6.3 Dock Locations - Possible Alternatives I 6.4 Webb Dock Facilities 6.5 Generation of Road Traffic I 6.6 Rail Service to Webb Dock 6'.7 'Environmental Considerations - General - Physical Aspects I 6.8 Environmental Considerations - Sociological Aspects I 7. TRANSPOHT ASSOCIATED 'HTH I{EST GATE AND' JOHNSON STHEET BRIDGE 1 7 . 1 Gen era,l 7.2 Initial Considerations I 7 • J Traffic Pr'edic tions 7.4 Recent Investigatio~s and Situation I 7.5 Subsequent Action and Progreis r .