A Gentle Introduction to South Indian Classical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Music Academy, Madras 115-E, Mowbray’S Road

Tyagaraja Bi-Centenary Volume THE JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS A QUARTERLY DEVOTED TO THE ADVANCEMENT OF THE SCIENCE AND ART OF MUSIC Vol. XXXIX 1968 Parts MV srri erarfa i “ I dwell not in Vaikuntha, nor in the hearts of Yogins, nor in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be I, Narada l ” EDITBD BY V. RAGHAVAN, M.A., p h .d . 1968 THE MUSIC ACADEMY, MADRAS 115-E, MOWBRAY’S ROAD. MADRAS-14 Annual Subscription—Inland Rs. 4. Foreign 8 sh. iI i & ADVERTISEMENT CHARGES ►j COVER PAGES: Full Page Half Page Back (outside) Rs. 25 Rs. 13 Front (inside) 20 11 Back (Do.) „ 30 „ 16 INSIDE PAGES: 1st page (after cover) „ 18 „ io Other pages (each) „ 15 „ 9 Preference will be given to advertisers of musical instruments and books and other artistic wares. Special positions and special rates on application. e iX NOTICE All correspondence should be addressed to Dr. V. Raghavan, Editor, Journal Of the Music Academy, Madras-14. « Articles on subjects of music and dance are accepted for mblication on the understanding that they are contributed solely o the Journal of the Music Academy. All manuscripts should be legibly written or preferably type written (double spaced—on one side of the paper only) and should >e signed by the writer (giving his address in full). The Editor of the Journal is not responsible for the views expressed by individual contributors. All books, advertisement moneys and cheques due to and intended for the Journal should be sent to Dr. V. Raghavan Editor. Pages. -

Syllabus for Post Graduate Programme in Music

1 Appendix to U.O.No.Acad/C1/13058/2020, dated 10.12.2020 KANNUR UNIVERSITY SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: MA MUSIC DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC KANNUR UNIVERSITY SWAMI ANANDA THEERTHA CAMPUS EDAT PO, PAYYANUR PIN: 670327 2 SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE PROGRAMME IN MUSIC UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SEMESTER SYSTEM FROM 2020 ADMISSION NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT: DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC NAME OF THE PROGRAMME: M A (MUSIC) ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT. The Department of Music, Kannur University was established in 2002. Department offers MA Music programme and PhD. So far 17 batches of students have passed out from this Department. This Department is the only institution offering PG programme in Music in Malabar area of Kerala. The Department is functioning at Swami Ananda Theertha Campus, Kannur University, Edat, Payyanur. The Department has a well-equipped library with more than 1800 books and subscription to over 10 Journals on Music. We have gooddigital collection of recordings of well-known musicians. The Department also possesses variety of musical instruments such as Tambura, Veena, Violin, Mridangam, Key board, Harmonium etc. The Department is active in the research of various facets of music. So far 7 scholars have been awarded Ph D and two Ph D thesis are under evaluation. Department of Music conducts Seminars, Lecture programmes and Music concerts. Department of Music has conducted seminars and workshops in collaboration with Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts-New Delhi, All India Radio, Zonal Cultural Centre under the Ministry of Culture, Government of India, and Folklore Academy, Kannur. -

Analyzing the Melodic Structure of a Raga-Based Song

Georgian Electronic Scientific Journal: Musicology and Cultural Science 2009 | No.2(4) A Statistical Analysis Of A Raga-Based Song Soubhik Chakraborty1*, Ripunjai Kumar Shukla2, Kolla Krishnapriya3, Loveleen4, Shivee Chauhan5, Mona Kumari6, Sandeep Singh Solanki7 1, 2Department of Applied Mathematics, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India 3-7Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering, BIT Mesra, Ranchi-835215, India * email: [email protected] Abstract The origins of Indian classical music lie in the cultural and spiritual values of India and go back to the Vedic Age. The art of music was, and still is, regarded as both holy and heavenly giving not only aesthetic pleasure but also inducing a joyful religious discipline. Emotion and devotion are the essential characteristics of Indian music from the aesthetic side. From the technical perspective, we talk about melody and rhythm. A raga, the nucleus of Indian classical music, may be defined as a melodic structure with fixed notes and a set of rules characterizing a certain mood conveyed by performance.. The strength of raga-based songs, although they generally do not quite maintain the raga correctly, in promoting Indian classical music among laymen cannot be thrown away. The present paper analyzes an old and popular playback song based on the raga Bhairavi using a statistical approach, thereby extending our previous work from pure classical music to a semi-classical paradigm. The analysis consists of forming melody groups of notes and measuring the significance of these groups and segments, analysis of lengths of melody groups, comparing melody groups over similarity etc. Finally, the paper raises the question “What % of a raga is contained in a song?” as an open research problem demanding an in-depth statistical investigation. -

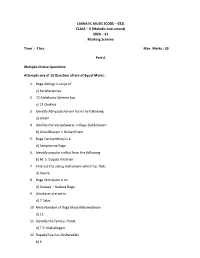

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Marking Scheme Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has c) 12 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri b) GhanDharam – NishanDham 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to d) 7 Talas 10 Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals b) 6 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis c) MuthuswaniDikshitan 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. Raga SuddaDeven is Janya of a) Sankarabharanam 16. Composer of Famous GhanePanchartnaKritis – identify a) Thyagaraja 17. Find out most important accompanying instrument for a vocal concert b) Mridangam 18. A musical form set to different ragas c) Ragamalika 19. Identify dance from of music b) Tillana 20. Raga Sri Ranjani is Janya of a) Karahara Priya 21. Find out the popular Vena artist d) S. Bala Chander Part B Answer any five questions. All questions carry equal marks 5X3 = 15 1. Gitam : Gitam are the simplest musical form. The term “Gita” means song it is melodic extension of raga in which it is composed. -

Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan

Table of Contents From the Publications & Outreach Committee ..................................... Lakshmi Radhakrishnan ............ 1 From the President’s Desk ...................................................................... Balaji Raghothaman .................. 2 Connect with SRUTI ............................................................................................................................ 4 SRUTI at 30 – Some reflections…………………………………. ........... Mani, Dinakar, Uma & Balaji .. 5 A Mellifluous Ode to Devi by Sikkil Gurucharan & Anil Srinivasan… .. Kamakshi Mallikarjun ............. 11 Concert – Sanjay Subrahmanyan……………………………Revathi Subramony & Sanjana Narayanan ..... 14 A Grand Violin Trio Concert ................................................................... Sneha Ramesh Mani ................ 16 What is in a raga’s identity – label or the notes?? ................................... P. Swaminathan ...................... 18 Saayujya by T.M.Krishna & Priyadarsini Govind ................................... Toni Shapiro-Phim .................. 20 And the Oscar goes to …… Kaapi – Bombay Jayashree Concert .......... P. Sivakumar ......................... 24 Saarangi – Harsh Narayan ...................................................................... Allyn Miner ........................... 26 Lec-Dem on Bharat Ratna MS Subbulakshmi by RK Shriramkumar .... Prabhakar Chitrapu ................ 28 Bala Bhavam – Bharatanatyam by Rumya Venkateshwaran ................. Roopa Nayak ......................... 33 Dr. M. Balamurali -

The Maha Melaragamalika (Part 2) Sumithra Vasudev

ANALYSIS The maha melaragamalika (part 2) Sumithra Vasudev n this article, which is the second in the series on the Melaragamalika of Maha Vaidyanatha Sivan, let us focus on the Ilyrical features of this masterpiece. As mentioned in the September issue of Sruti, the language employed in this ragamalika is Sanskrit. The sahitya for each raga section extends to two avartas of Adi tala. The name of each of the 72 melakarta ragas is embedded very skillfully and beautifully in the respective sahitya portions. The lyrical features and excellences in this composition can be studied with reference to two fundamental aspects of sahitya— namely sabda or word, and artha or meaning, and sometimes as a combination of both. Let us first take up the sabda aspect. Among the embellishments or alankaras of sabda that are commonly used in our musical literature, prasa (also commonly referred to as dviteeyakshara prasa), and antyaprasa (denoting the repetition of specific letters at particular intervals of the sahitya portions) are extensively employed. Apart from enhancing the verbal aesthetic, they help in the blending of sahitya and melody apart from showcasing the skill of the author- composer and his mastery over the language. In Sanskrit literature, there is anuprasa which also involves repetition of letters, but there is no rigid regulation for the repetition. The usage of muhanaa, prasa and antyaprasa are quite common in Carnatic music compositions. Muhanaa refers to repetition or concordance of letters at the beginning of the avarta. Repetition Maha Vaidyanatha Sivan of a group of letters is known as yamaka. Examples of all these— muhanaa, prasa, antyaprasa and yamaka can be found throughout the A combination of sabda and artha aspects are Melaragamalika. -

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Sample Question Paper

CARNATIC MUSIC (CODE – 032) CLASS – X (Melodic Instrument) 2020 – 21 Sample Question Paper Time - 2 hrs. Max. Marks : 30 Part A Multiple Choice Questions: Attempts any of 15 Question all are of Equal Marks : 1. Raga Abhogi is Janya of a) Karaharapriya b) NataBhiravi c) HariKambhoji d) DheeraSankaraBharanam 2. 72 Melakarta Scheme has a) 6 Chakaras b) 9 Chakras c) 12 Chakras d) 36 Chakras 3. Identify AbhyasaGhanam form the following a) Kriti b) Raga Malika c) Tillana d) Gitam 4. Idenfity the VarjyaSwaras in Raga SuddoSaveri a) Madhyama – Nisha Dam b) GhanDharam – NishanDham c) NishaDham- Rishabam d) Dhaviatam – Nadgtanan 5. Raga Harikambhoji is a a) Audava Raga b) Shadava Raga c) Bhashanga Raga d) Sampoorna Raga 6. Identify popular vidilist from the following a) S BalaChander b) M. S. Gopala Krishnan c) G. N. BalaSubrmanyam d) PopanasamSiram 7. Find out the string instrument which has frets a) Violin b) Thanpur c) Sarangi d) Veena 8. Raga Mohanam is an a) Audav-Shadava Raga b) Shadava – Audava Raga c) Janaka- Raga d) Audava – Audava Raga 9. Alankaras are set to a) 9 Talas b) 5 Talas c) 6 Talas d) 7 Talas 10 .Mela Number of Raga Maya MalawaGoula a) 22 b) 28 c) 20 d) 15 11. Identify the famous flutist a) LalgadiJayaraman b) Papanaseem Sivan c) S. BalaChander d) T R. Mahalingam 12. RupakaTala has AksharaKals a) 3 b) 6 c) 9 d) 12 13. Indentify composer of Navagrehakritis a) Balamurali Krishna b) KoliswaraIyer c) MuthuswaniDikshitan d) G. N. Balasubramanam 14. Essential angas of kriti are a) Pallavi-Anuppallavi- Charanam b) Pallavi –multifplecharanma c) Pallavi – MukkyiSwaram d) Pallavi – Charanam 15. -

Carnatic Music Primer

A KARNATIC MUSIC PRIMER P. Sriram PUBLISHED BY The Carnatic Music Association of North America, Inc. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Dr. Parthasarathy Sriram, is an aerospace engineer, with a bachelor’s degree from IIT, Madras (1982) and a Ph.D. from Georgia Institute of Technology where is currently a research engineer in the Dept. of Aerospace Engineering. The preface written by Dr. Sriram speaks of why he wrote this monograph. At present Dr. Sriram is looking after the affairs of the provisionally recognized South Eastern chapter of the Carnatic Music Association of North America in Atlanta, Georgia. CMANA is very privileged to publish this scientific approach to Carnatic Music written by a young student of music. © copyright by CMANA, 375 Ridgewood Ave, Paramus, New Jersey 1990 Price: $3.00 Table of Contents Preface...........................................................................................................................i Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Swaras and Swarasthanas..........................................................................................5 Ragas.............................................................................................................................10 The Melakarta Scheme ...............................................................................................12 Janya Ragas .................................................................................................................23 -

Vol.74-76 2003-2005.Pdf

ISSN. 0970-3101 THE JOURNAL Of THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Devoted to the Advancement of the Science and Art of Music Vol. LXXIV 2003 ^ JllilPd frTBrf^ ^TTT^ II “I dwell not in Vaikunta, nor in the hearts of Yogins, not in the Sun; (but) where my Bhaktas sing, there be /, N arada !” Narada Bhakti Sutra EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. V.V. Srivatsa (Editor) N. Murali, President (Ex. Officio) Dr. Malathi Rangaswami (Convenor) Sulochana Pattabhi Raman Lakshmi Viswanathan Dr. SA.K. Durga Dr. Pappu Venugopala Rao V. Sriram THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS New No. 168 (Old No. 306), T.T.K. Road, Chennai 600 014. Email : [email protected] Website : www.musicacademymadras.in ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION - INLAND Rs. 150 FOREIGN US $ 5 Statement about ownership and other particulars about newspaper “JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS” Chennai as required to be published under Section 19-D sub-section (B) of the Press and Registration Books Act read with rule 8 of the Registration of Newspapers (Central Rules) 1956. FORM IV JOURNAL OF THE MUSIC ACADEMY MADRAS Place of Publication Chennai All Correspondence relating to the journal should be addressed Periodicity of Publication and all books etc., intended for it should be sent in duplicate to the Annual Editor, The journal o f the Music Academy Madras, New 168 (Old 306), Printer Mr. N Subramanian T.T.K. Road, Chennai 600 014. 14, Neelakanta Mehta Street Articles on music and dance are accepted for publication on the T Nagar, Chennai 600 017 recommendation of the Editor. The Editor reserves the right to accept Publisher Dr. -

Mukherji-Handout-0056.Pdf

Rāga as Scale 42nd Annual Conference of the Society for Music Theory November 7, 2019 Columbus OH USA Sam Mukherji University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ([email protected]) 2 Example 1. Two theorists of North Indian classical music Vishnu Narayan Bhatkhande (1860–1936) Omkarnath Thakur (1897–1967) 3 phrases (1 and 3 performed by Amjad Ali Khan, 2 and 4 performed by Buddhadev Das Gupta) Ali2 and by Khan, (1 and Amjad 4 performed 3 performed phrases rāga Example 2. Four Example 2. Four 4 Example 3. Bhatkhande’s list of ten tḥāṭs, from his Hindustānī Sangīta Paddhatī (1909-32) Tḥāṭ Scale structure (centered on C) Western equivalent Pūrvī C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Mārvā C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Kalyān Lydian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Bilāval Major, or Ionian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Khamāj Mixolydian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Kāfi Dorian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Āsāvari Natural minor, or Aeolian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Bhairavī Phrygian C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Bhairav C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Tōdī C Db Eb F# G Ab Bb C Example 4. Thakur’s list of six pedagogical rāgas, from his Sangītānjalī (1938-62) Name Rāga scale (centered on C) Forbidden scale degrees Bhoop C D E F G A B C 4 and 7 Hamsadhvanī C D E F G A B C 4 and 6 Durgā C D E F G A B C 3 and 7 Sārang C D E F G A B C 3 and 6 Tilang C D E F G A B C 2 and 6 Bhinna-shadạj C D E F G A B C 2 and 5 5 Example 5. -

Transcription and Analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love For

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura Bethany Padgett Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Padgett, Bethany, "Transcription and analysis of Ravi Shankar's Morning Love for Western flute, sitar, tabla and tanpura" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 511. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/511 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. TRANSCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS OF RAVI SHANKAR’S MORNING LOVE FOR WESTERN FLUTE, SITAR, TABLA AND TANPURA A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Bethany Padgett B.M., Western Michigan University, 2007 M.M., Illinois State University, 2010 August 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am entirely indebted to many individuals who have encouraged my musical endeavors and research and made this project and my degree possible. I would first and foremost like to thank Dr. Katherine Kemler, professor of flute at Louisiana State University. She has been more than I could have ever hoped for in an advisor and mentor for the past three years. -

A Method for Quantifying Raga Similarity

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 10, ISSUE 06, JUNE 2021 ISSN 2277-8616 Ragadist: A Method For Quantifying Raga Similarity Vinuraj Devaraj Abstract: Raga Similarity had been a topic of fascination among Karnatik music followers. Though the topic remains active and interesting, a lack of appropriate similarity quantification method leads to subjective interpretations which in turn can be ambiguous intermittently. In this paper, we propose a raga similarity method, RagaDist, that quantifies similarities between raga pairs, based on their semantic structure and classifies the similarity into a 4- scale measure. Similarities derived using RagaDist is compared with popular string similarity methods using clustering approaches – Hierarchical clustering and Partition Around Medoids (PAM) and Multi-Dimensional Scaling (MDS) methods to analyze emerging patterns and characteristics among Melakarta raga similarities. Empirical measurements were conducted using one-way ANOVA and post hoc analysis. We also determined that using RagaDist, a threshold of 0.79 may be used as a cut off to distinguish ragas based on similarity. Index Terms: Multi-Dimensional Scaling, Correlation Analysis, Clustering, Partition Around Medoids (PAM), Levenshtein distance, ANOVA, Karnatik Ragas. ———————————————————— 1 INTRODUCTION KARNATIK Music is an ancient, sophisticated yet refined art form of delivering mesmerizing music through a structured In its core, Karnatik ragas are based on sapta swaras or seven method. This form of art is predominantly practiced in South musical notes viz. ―Sa‖, ―Ri‖, ―Ga‖, ―Ma‖, ―Pa‖, ―Dha‖ and ―Ni‖. India and this form of music is still the foundation for various The figure 1 below represents solfeggio of Karnatik raga as musical compositions that are emerging in several forms of represented on a single octave of a piano.