B4905.Pdf (7.847Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Strategy in Teaching English for Deaf

Jurnal Dialektika Program Studi Pendidikan Bahasa Inggris Vol. 9 No.1 March 2021 – August 2021 Page 34 - 51 TEACHER’S STRATEGY IN TEACHING ENGLISH FOR DEAF STUDENTS AT SLB MANUNGGAL SLAWI - TEGAL Nur Hamidah 1 Dede Nurdiawati 2 1 the Graduate of English Education Study Program Universitas Peradaban Bumiayu – Brebes Email: [email protected] Phone: +62 823 1448 9696 2 the Lecturer of English Education Study Program Universitas Peradaban Bumiayu – Brebes Email: [email protected] Phone: +62 877 1030 5577 Abstract Teaching English for disability or special needs students is a challenge requires specific method or strategy and needs participation of all parties within the school. Deafness is one kind of physical disability. Teaching English to deaf student is so hard. The research is aimed at describing teacher’s strategy in teaching English for deaf students at SLB Manunggal Slawi. Qualitative approach is used in this research. Techniques of data collection used are observation, interview, and documentation (image). To analyse the data obtained, the writers use data collection technique, data reduction, data display, and conclusion. The result of this study shows that the teacher emphasizes 34 Nur Hamidah, Dede Nurdiawati on conducting effective lesson by repeating the material and checking students’ understanding periodically, individualizing instructional practices in measure each student’s ability and students’ sitting position as the classroom accommodation as her strategy for teaching deaf students. She uses Total Physical Response, Grammar Translation Method as the English language development strategies in teaching English for deaf students combined with oral speech and sign language used, SIBI. It can be concluded that the goal of teaching English by using those strategies can be achieved. -

User's Guide for the Indonesia Family Life Survey, Wave 4

User's Guide for the Indonesia Family Life Survey, Wave 4 AND ANNA MARIE WATTIE We recommend the following citations for the IFLS data: For papers using IFLS1 (1993): Frankenberg, E. and L. Karoly. "The 1993 Indonesian Family Life Survey: Overview and Field Report." November, 1995. RAND. DRU-1195/1-NICHD/AID For papers using IFLS2 (1997): Frankenberg, E. and D. Thomas. ―The Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS): Study Design and Results from Waves 1 and 2‖. March, 2000. DRU-2238/1-NIA/NICHD. For papers using IFLS3 (2000): Strauss, J., K. Beegle, B. Sikoki, A. Dwiyanto, Y. Herawati and F. Witoelar. ―The Third Wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS3): Overview and Field Report‖. March 2004. WR-144/1- NIA/NICHD. For papers using IFLS4 (2007): Strauss, J., F. Witoelar, B. Sikoki and AM Wattie. ―The Fourth Wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS4): Overview and Field Report‖. March 2009. WR-675/1-NIA/NICHD. ii Preface This document describes some issues related to use of the fourth wave of the Indonesia Family Life Survey (IFLS4), alone and together with earlier waves of IFLS: IFLS1, 2 and 3. It is the second of six volumes documenting IFLS4. The first volume describes the basic survey design and implementation. The Indonesia Family Life Survey is a continuing longitudinal socioeconomic and health survey. It is based on a sample of households representing about 83% of the Indonesian population living in 13 of the nation’s 26 provinces in 1993. The survey collects data on individual respondents, their families, their households, the communities in which they live, and the health and education facilities they use. -

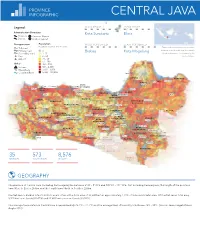

Central Java

PROVINCE INFOGRAPHIC CENTRAL JAVA Legend: MOST DENSE LEAST DENSE Administrative Boundary Kota Surakarta Blora Province Province Capital District District Capital Transportation Population MOST POPULATED LEAST POPULATED Population counts at 1km resolution Toll road The boundaries and names shown and the Primary road 0 Brebes Kota Magelang designations used on this map do not imply Secondary road 1 - 5 official endorsement or acceptance by the Port 6 - 25 United Nations. Airport 26 - 50 51 - 100 Other 101 - 500 INDRAMAYVolcanoU 501 - 2,500 Water/Lake 2,501 - 5,000 Coastline/River 5,000 - 130,000 Jepara Cirebon JEPARA REMBA NG Rembang KOTA Pati PATI KUDUS CIREBON Kudus CIREBON KOTA Tegal Pemalang PEKALON GAN Brebes KOTA Kendal Demak TEGAL Pekalongan TUB AN Semarang DEMAK KEND AL Slawi Batang Semarang Blora KUNINGAN KOTA SEMA RANG Kajen BATANG TEGAL Purwodadi PEMA LAN G GROBOGA N BOYOLALI PEKALON GAN Ungaran Ungaran Dieng Volc Complex BREB ES Slamet TEMA NGGUN G SEMA RANG BLORA BOJONEGO RO PURB ALINGGA Sundoro Salatiga KOTA BANJARN EGARA Wonosobo Temanggung KOTA BANJAR BANYUMAS Banjarnegara Sumbing Banjar TelomoyoSALATIGA SRAGEN NGAWI Purbalingga KOTA Purwokerto WONO SOBO Sragen Ngawi MA GELANG Merbabu Magelang Boyolali Surakarta MA GELANG Merapi KOTA CIAMIS KEBU MEN Mungkid Caruban SURAKARTA Karanganyar Madiun KOTA MA DIU N CILACAP Lawu Kebumen SUKO HARJO Magetan Purworejo SLEMAN Klaten MA DIU N Parigi Sukoharjo KARANGANYAR MAGETAN Cilacap KOTA Sleman PURWOREJO KLATEN NGANJUK YOGYAKARTA Yogyakarta Wonogiri Wates Yogyakarta KULON Ponorogo Bantul PROGO WONO GIRI PONOROGO BANTUL 35 573 8,576 Wonosari DISTRICTS SUB-DISTRICTS VILLAGES GUNUN G Trenggalek KIDU L PACITAN Pacitan TRENGGALEK TULUNGA GUNG GEOGRAPHY The province of Central Java (including Karimunjawa) lies between 5°40' - 8°30'S and 108°30' - 111°30'E. -

Mints Misr National Itinerary Transport Study

MiNTS Misr National Itinerary Transport Study Counterpart Training Program Stage 1 – Knowledge Building Stage Day 2 - Session 1 1 MiNTS Misr National What’s GIS? Transport Study • Geographic Information System (GIS) is “a computer application used to store, view, and analyze geographical information, especially maps”. 2 (Source: American Heritage Dictionary) A1-60 1 MiNTS Misr National Layer and Dataset Transport Study There are various geographic features such as administrative boundary, transportation, land use, census result, structures and so force. Data types are also various including numerical results of mapping survey, photo image, address and zip code. GIS relate all these data and enable cross-layer analysis on computer. 3 MiNTSAdvantages of GIS compared with Misr National Transport Study Paper Map GIS is … • Multiscale – Zoom in and out freely • Interactive – Overlay function ease interactive analyses • Software with Many Applications – Tools such as map editing, geographical analyses, routing, geocoding etc • Multiple Source – Many kind of source of information can be • Flexible – A variety of GIS map applications and frameworks support a wide range of deployment options such as original software or website 4 A1-61 2 MiNTS Misr National 3 functions and views of GIS Transport Study • Geodatabase – A GIS is a spatial database containing datasets such as features, rasters, attributes, topologies, networks, and so forth. • Geoprocessing – A GIS is a set of intelligent maps and other views that show features and feature relationships on the earth’ s surface. • Geovisualization – A GIS is a set of information transformation tools that derive new information from existing datasets. 5 MiNTS Misr National Type of GIS dataset Transport Study • Vector data – ex. -

Daftar Penyalur LPG Pertamina

DAFTAR PENYALUR LPG PT PERTAMINA (PERSERO) No. Nama Penyalur Region Jenis Penyaluran LPG Wilayah Penyaluran Alamat Penyalur 1 PT. KISARAN SARI MEGAH 1 Umum Kab.Serdang Bedagai, Kota T.Tinggi, Kota Tg.Balai, Kab.Asahan, Kab. Labuhan Batu Tanjung Balai 2 PT. ASAHAN GASINDO ABADI 1 Umum Kabupaten Serdang Bedagai, Kota Tebing Tinggi, Kab. Asahan dan Kab. Labuhan Batu JL.M.Yamin No.7 Kel.Kisaran Naga, Kec.Kisaran Timur Kab Asahan 3 PT. BIRANTA NUSANTARA 1 Umum 4 PT. JALAHAN ARTHA PRIMA 1 Umum Labuhan Batu Jl.Sisingamangaraja No.67 A Rantau Prapat Kab.Serdang Bedagai, Kota Tebing Tinggi, Kabupaten Batu Bara, Kabupaten Asahan/Tanjung Balai, 5 PT. WIRA PRATAMA GASINDO 1 Umum Kab.Labuhan Batu Rantau Prapat 6 PT. SINAR SAKINAH SEJAHTERA 1 Umum Kab. Padang Lawas Desa Sialambue, Kec. Barumun - Padang Lawas 7 PT. SABUNGAN JAYA 1 Umum Tapanuli Utara JL. DI Panjaitan No. 24 Kel. Partali toruan Kec.Tarutung Kab. Tapanuli Utara 8 PT. NAULI TAPANULI JAYA 1 Umum Kota Sibolga, Kab. Tapanuli Tengah, Kab. Tapanuli Selatan, Kab. Mandailing Natal dan Kab. Nias Jl. Gatot Subroto, Kelurahan Pondok Batu, Kecamatan Sarudik 9 PT. BINTANG TAPANULI 1 Umum PSP, Madina, Sibolga, Tapanuli Tengah, Tapanuli Selatan, Padang Lawas, Padang Lawas Utara Jl. WR Supratman Kota Sibolga, Kab.Tapanuli Tengah, Kota Padangsidimpuan, Kab. Tapanuli Selatan, Kab. Padang Lawas, 10 PT. TAPTENG JAYA 1 Umum Kab. Madina, Kota Gunung Sitoli, Kab. Nias, Kab. Nias Barat, Kab Nias Utara, Kab. Nias Selatan Jalan Mesjid No. 10 Kota Sibolga 11 PT. CAHAYA MADINA 1 Umum Kab. Mandailing Natal Pidoli Lombang 12 PT. -

Editor's Introduction Cross-Regional Trade Cooperation

A publication of the University of San Francisco Center for the Pacific Rim Copyright 2007 Volume VII · Number 1 15 July · 2007 Editors Joaquin Gonzalez Editor’s Introduction John Nelson >>..................................................Joaquin L. Gonzalez III 1 Graduate Student Editor Cross-Regional Trade Cooperation: The Mexico-Japan Free Trade Agreement John Dzida >>.............................................................Sarita D. Jackson 2 Editorial Consultants Barbara K. Bundy ASEAN Regionalism: Growth Through Integration Hartmut Fischer Patrick L. Hatcher >>.................................................................Richard Payne 11 Richard J. Kozicki Stephen Uhalley, Jr. Xiaoxin Wu The Role of Government in Technology Transfer to SME Clusters in Indonesia: Case Study of the Metal Working Industry Cluster in Tegal (Central Java) Editorial Board Yoko Arisaka >>.............................................................Tulus Tambunan 20 Bih-hsya Hsieh Uldis Kruze A Futuristic Look into the Filipino Diaspora: Trends, Issues, and Implications Man-lui Lau Mark Mir >>................................................Soledad Rica R. Llorente 33 Noriko Nagata Stephen Roddy Kyoko Suda Bruce Wydick Asia Pacific: Perspectives is a peer-reviewed journal published at least once a year, usually in April/May. It wel- Asia Pacific: Perspectives comes submissions from all fields of the social sciences and the humanities with relevance to the Asia Pacific Center for the Pacific Rim region.* In keeping with the Jesuit traditions of the University of San Francisco, Asia Pacific: Perspectives com- 2130 Fulton St, LM202 mits itself to the highest standards of learning and scholarship. San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 Our task is to inform public opinion by a broad hospitality to divergent views and ideas that promote cross-cul- tural understanding, tolerance, and the dissemination of knowledge unreservedly. Papers adopting a compara- Tel: (415) 422-6357 Fax: (415) 422-5933 tive, interdisciplinary approach will be especially welcome. -

Alternative Dispute Resolution for Medical Malpractice Based on Restorative Justice in Central Java

South East Asia Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law, Vol. 18, Issue 4 (April) ISSN 2289-1560 2019 ALTERNATIVE DISPUTE RESOLUTION FOR MEDICAL MALPRACTICE BASED ON RESTORATIVE JUSTICE IN CENTRAL JAVA Cahya Wulandari ABSTRACT Dynamics of law matter is getting complicated. The law is expected to provide justice for the victims often cannot meet the wishes of the parties, particularly for the victims. Therefore, in the current development, emerging process a criminal settlement cases based on restorative justice. The type of settlement, offered is by confronted the parties, offender, victim and sometimes involve the role of the community. The resolution of criminal cases that are offered known as penal mediation. Penal mediation based on restorative justice aims to bring justice by involving the parties (victims and offenders) and the community, so that it can satisfy the desired sense of fairness. The resolution of criminal cases is no longer merely procedural but more on the substance of resolution desired by the parties. Based on the results of the research were ever writers do, there are medical malpractice case resolution based on restorative justice with the aim to provide justice for the parties. It is certainly very exciting to peeled thoroughly in the article that contains some of the research results and the analysis in terms of the law related to the settlement of the matter outside of court proceedings by penal mediation thus achieved the agreement between the parties. Key words: Alternative Dispute Resolution; Medical Malpractice, Restorative Justice INTRODUCTION Health is one of the things that is absolutely needed by humans. -

A Social Factor of Language Shift in Elementary School Students

Ihda Rosdiana - Peer-Oriented Intervention: A Social Factor of Language Shift in Elementary School Students PEER-ORIENTED INTERVENTION: A SOCIAL FACTOR OF LANGUAGE SHIFT IN ELEMENTARY SCHOOL STUDENTS Ihda Rosdiana Pancasakti University, Tegal [email protected] Abstract This study aims at ascertaining the social factor causing the shifting of Bahasa Jawa Ngoko into Bahasa Indonesia among the elementary school students and confirming whether this phenomenon also occurs in all grades. The data were collected through observation and interview. Those data were analyzed using interactive analysis model (Milles & Huberman, 1994). There are two triangulations used in this research: source and method triangulations. Finally, the research found that peer- oriented intervention (Mrug et al,. 2001) functions as a social factor of language shift. However, this Javanese shift did not occur in the fifth grade students since they are from the same speech community. Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk mengetahui faktor sosial yang menyebabkan pergeseran Bahasa Jawa Ngoko dalam Bahasa Indonesia di kalangan siswa sekolah dasar dan memastikan apakah fenomena ini juga terjadi di semua kelas. Data dikumpulkan melalui pengamatan dan wawancara. Selanjutnya, data tersebut dianalisis dengan menerapkan model analisis interaktif (Milles &Huberman, 1994). Selain itu, penelitian ini menggunakan triangulasi sumber dan metode. Penelitian ini menemukan bahwa peer-oriented intervention berfungsi sebagai faktor sosial pergeseran bahasa. Namun, pergeseran Bahasa Jawa Ngoko ke Bahasa Indonesia ini tidak terjadi pada siswa kelas lima karena mereka berasal dari komunitas bahasa yang sama. Keywords : peer-oriented intervention, social factors, language shift, elementary school students INTRODUCTION Language shift occurs when a person or group of speakers of a particular language moves to a new place which has a different language, and they have to use that different language because it is the only means of communication. -

Association Between Pregnant Woman Class and Pregnancy Complication in Tegal District, Central Java

Journal of Maternal and Child Health (2016), 1(4): 214-219 https://doi.org/10.26911/thejmch.2016.01.04.02 Association Between Pregnant Woman Class and Pregnancy Complication in Tegal District, Central Java Siti Maryani1), Supriyadi Hari Respati2), Okid Parama Astirin3) 1)Academy of Midwifery Siti Fatimah, Slawi, Central Java 2)Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Moewardi Hospital, Surakarta 3)Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, Universitas Sebelas Maret ABSTRACT Background: Maternal mortality amounted to 33 cases in Tegal, Central Java, in 2015. The lea- ding cause of maternal mortality rate in Indonesia was obstetric complication, i.e 46.8%. Pregnan- cy complication may be affected by maternal age, parity, education, and maternal employment sta- tus. Various efforts have been implemented by the government to reduce maternal mortality rate, including pregnant woman class. The objective of the pregnant mother class is to increase maternal knowledge in risk factor detection and to increase their willingness to use antenatal care. This study aimed to estimate the association between pregnant woman class and pregnancy complica- tion, while controlling for confounding factors. Subjects and Method: This was an analytical observational with case control design. This study was conducted at Pagerbarang, Pangkah and Dukuhwaru Health Centers, Tegal, Central Java. A to- tal of 90 study subjects, consisting of 30 laboring women with complication and 60 without com- plication. The dependent variable was pregnancy complication. The independent variables were maternal age, parity, education, employment status, and participation in pregnant woman class. The data were collected by a set of questionnaire. The data on pregnancy complication was obtai- ned from the obstetric record at the health center. -

Daftar Penyalur Lpg Pt Pertamina (Persero) Region I

DAFTAR PENYALUR LPG PT PERTAMINA (PERSERO) REGION I NO. NAMA PENYALUR WILAYAH PENYALURAN ALAMAT GUDANG LPG TERTENTU 1 PT. MITRA ALAM JAYA Kota Banda Aceh Jl. Rombean Komp. Beuranda Indah No.9 Lamlagang B. Aceh 2 PT. AMALIA YUSRI Kota Banda Aceh Jl. ST Iskandar Muda No. 20 Punge Ujong Kecamatan Meuraxa Banda Aceh 3 KOPERASI PUSKOPAD ISKANDAR MUDA TNI Kota Banda Aceh Jl. Cut Nyak Dhien no.246 Lamteumen Timur B. Aceh 4 PT. RAYTA Kab. Aceh Tamiang Dusun Keude Meuku, Desa Ie Bintah, Kec. Manyak Payed, Kab. Aceh Tamiang 5 PT. MONA CAHAYA BUNDA Kab. Aceh Tamiang Jl.Veteran Kampung Tualang Baru Kec.Manyak Payed,Kab.Aceh Taming 6 PT. MORA GAH Kab. Aceh Tamiang Dsn Bakti Seunebok Punti Manyak Payed Kab. Aceh Tamiang 7 PT. MINYEUK GAH Kab. Aceh Besar JL. Mireuk Taman No. 8 Tanjung Daeh, Darussalam 8 CV. CITKA HOE SABEE Kab. Aceh Besar Jln. Laksamana Malahayati 9 CV. KANA MINYEUK TANOH Kab. Aceh Besar Jln. Tungkop Blang Bintang , lamceu,Kuta Baro, Aceh Besar 10 CV. GOOD GAS Kab. Aceh Besar JL.BLANG BINTANG LAMA DESA BABAH JURONG ACEH BESAR 11 PT. MINYEUK MYCO YULIATI YACOB Kab. Aceh Besar Gampong Weusiteh Kec. Sukamakmur Kab. Aceh Besar 12 CV. GAPURA PUTRA MANDIRI Kab. Aceh Timur Jl. Medan-Banda Aceh Desa Tanoh Anou, Kec. Idi Reyeuk, Kab. Aceh Timur 13 PT. CUGA Kab. Aceh Timur Dsn Tani Jaya, Kampung Birem Rayeuk, Birem Bayeun, Kab. Aceh Timur 14 PT. HARAPAN MINYAK TANAH Kab. Aceh Timur JL.Medan-Banda Aceh Snb Teungoh Idi timur Kab. Aceh Timur 15 PT. -

Corporate Social Responsibility for City Branding in Slawi Caentral Java

Corporate Social Responsibility for City Branding in Slawi Caentral Java Richard Mayopu dan Radius Tanone Fakultas Teknologi Informasi Universitas Kristen Satya Wacana � [email protected] & [email protected] Pendahuluan Dalam perkembangan dunia Public Relations, Corporate Social Responsibility atau yang lebih sering dikenal dengan istilah CSR pun berkembang seiring mengkatnya kebutuhan tersebut. peraturan pemerintah yang menetapkan semua perusahan yang disebutkan dalam Undang-undang untuk menyisihkan sebagian anggarannya untuk dipergunakan sebagai dana pengembangan berbagai sektor ini memiliki dampak yang sangat signifikan terhadap perkembangan suatu kota. dibawah ini merupakan penjelasan Undang-undang yang mengatur CSR dalam Perseroan Terbatas1. jauh lebih penting dari itu adalah perkembangan bagi masyarakat yang bisa menikmati secara langsung dampak dari CSR itu sendiri. beberapa wilayah di Indonesia sudah menerapkan dan memanfaatkan Undang-undang ini untuk berkontribusi lebih dalam pembangunan masyarakat tersebut. Namun tidak sedikit pihak yang menolak keharusan melakukan CSR dari perusahan kepada pemerintah maupun masyarakat. Dengan dalih bahwa perusahan adalah lembaga profit yang mengurusi bisnis bukan mengurusi CSR. bahkan beberapa pandangan pesimistis yang mengemuka bahwa para investor akan memilih untuk melakukan investasi di negara lain daripada di Indonesia. Selain itu, pandangan bahwa pihak pemerintah hanya berusaha membuat regulasi hanya 1 Undang-Undang No. 40 Tahun 2007 tentang Perseroan Terbatas (“UUPT”) serta Peraturan -

Factors Causing Language Loss Experienced by an American Native Speaker in Multilingual Situation in Indonesia 1

167 Factors Causing Language Loss Experienced by an American Native Speaker in Multilingual Situation in Indonesia 1 Saptina Retnawati Universitas Pamulang, Banten, Indonesia Email: [email protected] Abstract: Bilingualism and multilingualism are common phenomena in language use. Those who are bilinguals or multilingual normally get the language competence because they are living in multilingual area, or in a country which has variety of languages and cultures. Indonesia is one of countries which have this wide diversity in cultures, languages, and religions. Furthermore, Indonesian Ministry of Education created a program called Darmasiswa program which enabled students from abroad to study Bahasa Indonesia and Indonesian cultures. By following this program, those students are learning new language and culture in multilingual situation. One of evidences occurred with a student from America, named Angela who also has multilingual family background. She was exposed to a lot of languages since she was born, and she also studied new languages in Indonesia, as a result she has capability to speak more than two languages. In this kind of situation, the researcher was interested to find out the language loss she might experience during her study. This study aimed to find factors influenced on language loss by her. The approach of this study was qualitative. The researcher applied mixed techniques to obtain data; recording the conversations in natural setting and interview. The analysis was interpretive. The findings of this study found that there were two factors that influenced language loss; internal factors and external factors, which dominated by cultural factor. Also, it happened because of the fact that Bahasa Indonesia is more dominant than her mother tongues.