Re-Vegetation and Rehabilitation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 3: Operational Phase Empr

Volume 3: Operational Phase EMPr Sibaya 5: EIA 5809 August 2014 Tongaat Hulett Developments (Pty) Ltd Volume 3: Operational Phase EMPr 286854 SSA RSA 10 1 EMPr Vol 3 August 2014 Volume 3: Operational Phase EMPr Sibaya 5: EIA 5809 Sibaya 5: EIA 5809 August 2014 Tongaat Hulett Developments (Pty) Ltd PO Box 22319, Glenashley, 4022 Mott MacDonald PDNA, 635 Peter Mokaba Ridge (formerly Ridge Road), Durban 4001, South Africa PO Box 37002, Overport 4067, South Africa T +27 (0)31 275 6900 F +27 (0) 31 275 6999 W www.mottmacpdna.co.za Sibaya 5: EIA 5809 Contents Chapter Title Page 1 Introduction 1 1.1 General ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 1.2 Node 5 – Site Location & Development Proposal ___________________________________________ 1 2 Operational Phase EMPr 2 3 Contact Details 4 Appendices 6 Appendix A. Landscape & Rehabilitation Plan _______________________________________________________ 7 286854/SSA/RSA/10/1 August 2014 EMPr Vol 3 Volume 3: Operational Phase EMPr Sibaya 5: EIA 5809 1 Introduction 1.1 General This document should be reviewed in conjunction with the Environmental Scoping Report and Environmental Impact Report (EIR) (EIA 5809). It is the intention that this document addresses the issues pertaining to the planning and development of the roads and infrastructure of Node 5 of the Sibaya Precinct. 1.2 Node 5 – Site Location & Development Proposal Node 5 comprises the development area to the east of the M4 above the southern portion of Umdloti (west of the Mhlanga Forest). It consists of commercial/ mixed use sites, 130 room hotel/ resort as well as low and medium density residential sites. -

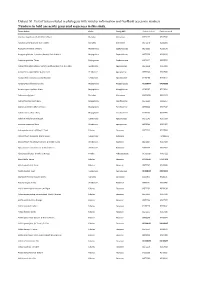

Dataset S1. List of Taxa Included in Phylogeny with Voucher Information and Genbank Accession Numbers

Dataset S1. List of taxa included in phylogeny with voucher information and GenBank accession numbers. Numbers in bold are newly generated sequences in this study. Taxon Author Order Family APG Genbank rbcLa Genbank matK Abutilon angulatum (Guill. & Perr.) Mast. Malvales Malvaceae JX572177 JX517944 Abutilon sonneratianum (Cav.) Sweet Malvales Malvaceae JX572178 JX518201 Acalypha chirindica S.Moore Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae JX572236 JX518178 Acalypha glabrata f. pilosior (Kuntze) Prain & Hutch. Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae JX572238 JX518120 Acalypha glabrata Thunb. Malpighiales Euphorbiaceae JX572237 JX517655 Acokanthera oblongifolia (Hochst.) Benth. & Hook.f. ex B.D.Jacks. Gentianales Apocynaceae JX572239 JX517911 Acokanthera oppositifolia (Lam.) Codd Gentianales Apocynaceae JX572240 JX517680 Acokanthera rotundata (Codd) Kupicha Gentianales Apocynaceae JF265266 JF270623 Acridocarpus chloropterus Oliv. Malpighiales Malpighiaceae KU568077 KX146299 Acridocarpus natalitius A.Juss. Malpighiales Malpighiaceae JF265267 JF270624 Adansonia digitata L. Malvales Malvaceae JQ025018 JQ024933 Adenia fruticosa Burtt Davy Malpighiales Passifloraceae JX572241 JX905957 Adenia gummifera (Harv.) Harms Malpighiales Passifloraceae JX572242 JX517347 Adenia spinosa Burtt Davy Malpighiales Passifloraceae JF265269 JX905950 Adenium multiflorum Klotzsch Gentianales Apocynaceae JX572243 JX517509 Adenium swazicum Stapf Gentianales Apocynaceae JX572244 JX517457 Adenopodia spicata (E.Mey.) C.Presl Fabales Fabaceae JX572245 JX517808 Afrocanthium lactescens (Hiern) Lantz -

Bioactive Natural Products from Sapindaceae Deterrent and Toxic Metabolites Against Insects

13 Bioactive Natural Products from Sapindaceae Deterrent and Toxic Metabolites Against Insects Martina Díaz and Carmen Rossini Laboratorio de Ecología Química, Facultad de Química, Universidad de la República, Uruguay 1. Introduction The Sapindaceae (soapberry family) is a family of flowering plants with about 2000 species occurring from temperate to tropical regions throughout the world. Members of this family have been widely studied for their pharmacological activities; being Paullinia and Dodonaea good examples of genera containing species with these properties. Besides, the family includes many species with economically valuable tropical fruits, and wood (Rodriguez 1958), as well as many genera with reported anti-insect activity. Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anti-diabetic properties are the pharmacological activities most commonly described for this family (Sofidiya et al. 2008; Simpson et al. 2010; Veeramani et al. 2010; Muthukumran et al. 2011). These activities are in some cases accounted for isolated phenolic compounds such as prenylated flavonoids (Niu et al. 2010), but in many cases, it is still unknown which are the active principles. Indeed, there are many studies of complex mixtures (crude aqueous or ethanolic extracts) from different species in which several other pharmacological activities have been described without characterization of the active compounds [e.g. antimigrane (Arulmozhi et al. 2005), anti-ulcerogenic (Dharmani et al. 2005), antimalarial (Waako et al. 2005), anti-microbial (Getie et al. 2003)]. Phytochemical studies on Sapindaceae species are abundant and various kinds of natural products have been isolated and elucidated. Examples of these are flavonoids from Dodonaea spp. (Getie et al. 2002; Wollenweber & Roitman 2007) and Koelreuteria spp. -

Landscape Design Protocol

COUNTRY ESTATE Landscape Design Protocol 1. INTRODUCTION Stoneford Country Estate creates an opportunity to start the landscaping process from scratch and contribute to the shaping of a natural environment, so unique, yet integral to the environment of the Outer West region of Durban in KwaZulu Natal. The sugarcane farmers destroyed the natural vegetation in the past by removing it to plant the sugar cane. We have the opportunity to replant the sugar cane fields with a mixture of indigenous species local to this area to resemble what was here many years ago. The replanting of the area will ensure the survival of the wild animals that still live in the natural environment left on site. Good landscaping can promote an attractive image and enhance and protect the desired natural environment of the estate. Landscaping apart from contributing to the aesthetics of the development also improve the quality of life for the people who buy into this development. For this reason every little bit of space, even privately owned land is required to make this estate work. Stoneford Country Estate is rehabilitating the common land back to grassland, forest and wetland. This is a long-term process needing all landowners to co-operate to create a bigger and better habitat for the wildlife. Every landowner has the responsibility to contribute to the improvement of the landscape to the benefit of all. The landscape is to be entirely indigenous and landowners are mandated to accept this and support the bigger philosophy of nature first and man second. The list of indigenous plant material provided is best suited and adapted to this environment. -

A Preliminary Study of the Antiproliferative Properties Of

A PRELIMINARY STUDY OF THE ANTIPROLIFERATIVE PROPERTIES OF CRUDE BLIGHIA SAPIDA SEEDS EXTRACTS ON LUNG, PROSTATE, SKIN, LEUKEMIC CANCERS AND NORMAL HUMAN LIVER CELLS BY KWAME ADARKWA-YIADOM, B. Pharm (Hons) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY, KWAME NKRUMAH UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (BIOTECHNOLOGY) College of Science JUNE, 2018 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the MSc Biotechnology and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Kwame Adarkwa-Yiadom ………………………. ………………… (PG9996113) Signature Date Dr. Antonia Tetteh ………………………. ………………… (Supervisor) Signature Date Prof. Regina Appiah-Opong ………………………. ………………… (Supervisor) Signature Date Dr. Peter Twumasi ………………………. ………………… (Head of Department) Signature Date i DEDICATION To my wonderful and supportive family and lovely my wife, Anita Appiah-Kyere. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT My foremost gratitude goes to Almighty Jehovah God for his immense blessings in compiling this thesis. I also want to express my profound appreciation to my project supervisor, DR. (MRS) ANTONIA TETTEH, who carefully read through the first and subsequent drafts and made numerous valuable suggestions and contributions. It was indeed, a pleasure and privilege to be her student. Immense benefit and support was also received from Dr. Kwasi Amissah formerly of the Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, KNUST. I would also want to show my deepest appreciation to Prof Evans Adei of the Department of Chemistry, KNUST for helping me to transform my ideas into reality. -

Plant Communities of the Umlalazi Nature Reserve and Their Contribution to Conservation in Kwazulu-Natal

KOEDOE - African Protected Area Conservation and Science ISSN: (Online) 2071-0771, (Print) 0075-6458 Page 1 of 14 Original Research Plant communities of the uMlalazi Nature Reserve and their contribution to conservation in KwaZulu-Natal Authors: Vegetation research is an important tool for the simplified and effective identification, 1 Nqobile S. Zungu management and conservation of the very complex ecosystems underlying them. Plant Theo H.C. Mostert1 Rachel E. Mostert2 community descriptions offer scientists a summary and surrogate of all the biotic and abiotic factors shaping and driving ecosystems. The aim of this study was to identify, describe and Affiliations: map the plant communities within the uMlalazi Nature Reserve. A total of 149 vegetation plots 1 Department of Botany, were sampled using the Braun-Blanquet technique. Thirteen plant communities were identified University of Zululand, South Africa using a combination of numeric classification (modified Two-way-Indicator Species Analysis) and ordination (non-metric multidimensional scaling). These communities were described in 2Department of Biology, terms of their structure, floristic composition and distribution. An indirect gradient analysis of Felixton College, South Africa the ordination results was conducted to investigate the relationship between plant communities and their potentially important underlying environmental drivers. Based on the results, the Corresponding author: Theo Mostert, floristic conservation importance of each plant community was discussed to provide some [email protected] means to evaluate the relative contribution of the reserve to regional ecosystem conservation targets. Dates: Received: 18 Nov. 2017 Conservation implications: The uMlalazi Nature Reserve represents numerous ecosystems Accepted: 06 Feb. 2018 that are disappearing from a rapidly transforming landscape outside of formally protected Published: 28 May 2018 areas in Zululand. -

23 Chapter 2 Coastal Dune Forest in Context The

Chapter 2 - Coastal dune forest in context Chapter 2 Coastal dune forest in context The study area (between Richards Bay town and the Umfolozi River mouth) and the mining process are described in the methods sections of each of the following chapters (3 to 6). A map of the mining lease is available in Chapter 6 (Figure 6-1). To avoid repetition I limit this chapter to a characterisation of coastal dune forest and its historic and current threats. Characterisation of Coastal dune forest Broadly, there are two types of forest in South Africa, Afrotemperate Forests (also referred to as Afromontane Forest) and Indian Ocean Coastal Belt Forests, with an intermediate (in terms of species composition and geography) coastal scarp forest situated between the two groups (Lawes et al. 2004). Forests occur along the southern and eastern seaboard of South Africa and extend a short distance in to the interior across the Great Escarpment, mountain ranges, and coastal plains (Mucina et al. 2006). Approximately 7 % of South Africa’s land surface is climatically suitable for the development of forests, however forests comprise as little as 0.1 to 0.56 % (Mucina et al. 2006). Forests are generally fragmented and patches are very small (<100 hectares; Midgley et al. 1997). The threats to these forest patches include timber extraction, fuel-wood extraction, over-exploitation of plants and animals for food and traditional medicines, clearance for agriculture, clearance for housing, commercial plantations and mining (Lawes et al. 2004; Mucina et al. 2006). Therefore, an understanding of forest regeneration after disturbances is imperative to conserve and restore the disproportionate levels of biological diversity housed within South African forests (Lawes et al. -

Savanna Fire and the Origins of the “Underground Forests” of Africa

SAVANNA FIRE AND THE ORIGINS OF THE “UNDERGROUND FORESTS” OF AFRICA Olivier Maurin1, *, T. Jonathan Davies1, 2, *, John E. Burrows3, 4, Barnabas H. Daru1, Kowiyou Yessoufou1, 5, A. Muthama Muasya6, Michelle van der Bank1 and William J. Bond6, 7 1African Centre for DNA Barcoding, Department of Botany & Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, PO Box 524 Auckland Park 2006, Johannesburg, Gauteng, South Africa; 2Department of Biology, McGill University, 1205 ave Docteur Penfield, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4, Quebec, Canada; 3Buffelskloof Herbarium, P.O. Box 710, Lydenburg, 1120, South Africa; 4Department of Plant Sciences, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20 Hatfield 0028, Pretoria, South Africa; 5Department of Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa, Florida campus, Florida 1710, Gauteng, South Africa; 6Department of Biological Sciences and 7South African Environmental Observation Network, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, 7701, Western Cape, South Africa *These authors contributed equally to the study Author for correspondence: T. Jonathan Davies Tel: +1 514 398 8885 Email: [email protected] Manuscript information: 5272 words (Introduction = 1242 words, Materials and Methods = 1578 words, Results = 548 words, Discussion = 1627 words, Conclusion = 205 words | 6 figures (5 color figures) | 2 Tables | 2 supporting information 1 SUMMARY 1. The origin of fire-adapted lineages is a long-standing question in ecology. Although phylogeny can provide a significant contribution to the ongoing debate, its use has been precluded by the lack of comprehensive DNA data. Here we focus on the ‘underground trees’ (= geoxyles) of southern Africa, one of the most distinctive growth forms characteristic of fire-prone savannas. 2. We placed geoxyles within the most comprehensive dated phylogeny for the regional flora comprising over 1400 woody species. -

An Evaluation of Coastal Dune Forest Restoration in Northern Kwazulu-Natal

An evaluation of coastal dune forest restoration in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa by Matthew James Grainger Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Zoology) in the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences University of Pretoria Pretoria May 2011 © University of Pretoria An evaluation of coastal dune forest restoration in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa Student: Matthew J Grainger Supervisor: Rudi J van Aarde Conservation Ecology Research Unit Department of Zoology & Entomology University of Pretoria Pretoria 0002 [email protected] “One should always have a definite objective… it is so much more satisfying to reach a target by personal effort than to wander aimlessly. An objective is an ambition, and life without ambition is…well, aimless wandering.” A.W. Wainwright 1973 Abstract Ecological restoration has the potential to stem the tide of habitat loss, fragmentation and transformation that are the main threats to global biological diversity and ecosystem services. Through this thesis, I aimed to evaluate the ecological consequences of a 33 year old rehabilitation programme for coastal dune forest conservation. The mining company Richards Bay Minerals (RBM) initiated what is now the longest running rehabilitation programme in South Africa in 1977. Management of the rehabilitation process is founded upon the principles of ecological succession after ameliorating the mine tailings to accelerate initial colonisation. Many factors may detract from the predictability of the ecological succession. For example, if historical contingency is a reality, then the goal of restoring a particular habitat to its former state may be unattainable as a number of alternative stable states can result from the order by which species establish. -

Original Article a Novel Phylogenetic Regionalization of Phytogeographic

1 Article type: Original Article A novel phylogenetic regionalization of phytogeographic zones of southern Africa reveals their hidden evolutionary affinities Barnabas H. Daru1,2,*, Michelle van der Bank1, Olivier Maurin1, Kowiyou Yessoufou1,3, Hanno Schaefer4, Jasper A. Slingsby5,6, and T. Jonathan Davies1,7 1African Centre for DNA Barcoding, University of Johannesburg, APK Campus, PO Box 524, Auckland Park, 2006, Johannesburg, South Africa 2Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield 0028, South Africa 3Department of Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa, Florida Campus, Florida 1710, South Africa 4Technische Universität München, Plant Biodiversity Research, Emil-Ramann Strasse 2, 85354 Freising, Germany 5Fynbos Node, South African Environmental Observation Network, Private Bag X7, 7735, Rhodes Drive, Newlands, South Africa 6Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, Private Bag X3, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa 7Department of Biology, McGill University, Montreal, QC H3A 0G4, Canada *Correspondence: Barnabas H. Daru, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield 0028, South Africa. Journal of Biogeography 2 Email: [email protected] Running header: Phylogenetic regionalization of vegetation types Manuscript information: 266 words in the Abstract, 5060 words in manuscript, 78 literature citations, 22 text pages, 4 figures, 1 table, 4 supplemental figures, and 3 supplemental tables. Total word count (inclusive of abstract, text and references) = 7407. Journal of Biogeography 3 Abstract Aim: Whilst existing bioregional classification schemes often consider the compositional affinities within regional biotas, they do not typically incorporate phylogenetic information explicitly. Because phylogeny captures information on the evolutionary history of taxa, it provides a powerful tool for delineating biogeographic boundaries and for establishing relationships among them. -

Plant Rescue and Translocation Management Plan

APPENDIX F PLANT RESCUE AND TRANSLOCATION MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED CONSTRUCTION OF AN ADDITIONAL BIDVEST TANK TERMINAL (BTT) RAIL LINE AT SOUTH DUNES, WITHIN THE PORT OF RICHARDS BAY, KWAZULU-NATAL January 2017 Prepared For: Prepared By: Transnet National Ports Authority Acer (Africa) Environmental Consultants P O Box 181 P O Box 503 Richards Bay Mtunzini 3900 3867 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................... ii 1. PURPOSE ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. SCOPE .................................................................................................................................. 1 3. IDENTIFICATION OF SPECIES OF CONSERVATION CONCERN .................................... 1 3.1 Protected Tree Species ......................................................................................................... 2 3.3 Protected Plant Species ........................................................................................................ 2 3.1 Mitigation and Avoidance Options ........................................................................................ 2 4. PLANT RESCUE AND PROTECTION PLAN ....................................................................... 3 4.1 Preconstruction ..................................................................................................................... 3 4.2 -

Botanical Names Previous English Names

RECOMMENDED ENGLISH PREVIOUS BOTANICAL NAMES NAMES ENGLISH NAMES SPECIES & SUB SPECIES CYATHEACEAE Tree Fern Cyathea Tree-fern Cyathea capensis Forest Tree Fern Forest Tree-fern Cyathea dregei Common Tree Fern Grassland Tree-fern ZAMIACEAE Cycad Encephalartos African Cycad Encephalartos aemulans Ngotshe Cycad Encephalartos altensteinii Eastern Cape-cycad Giant-cycad Encephalartos arenarius Alexandria Cycad Encephalartos brevifoliolatus Escarpment Cycad Encephalartos dolomiticus Wolkberg Cycad Encephalartos dyerianus Lillie Cycad Encephalartos eugene-maraisii Waterberg Cycad Encephalartos ferox Tonga Cycad Encephalartos friderici-guilielmi White-haired Cycad Encephalartos ghellinckii Drakensberg Cycad Encephalartos heenanii Woolly Cycad Encephalartos hirsutus Northern Cycad Venda Cycad Encephalartos inopinus Lydenburg Cycad Encephalartos laevifolius Kaapsehoop Cycad Encephalartos lanatus Olifants River Cycad Encephalartos latifrons Albany Cycad Encephalartos lebomboensis Lebombo Cycad Encephalartos lehmannii Karoo Cycad Encephalartos longifolius Suurberg Cycad Encephalartos middelburgensis Middelburg Giant Cycad Giant-cycad Encephalartos msinganus Msinga Cycad Encephalartos natalensis Natal Cycad Prickly Giant-cycad Encephalartos paucidentatus Barberton Cycad Encephalartos princeps Kei Cycad Encephalartos senticosus Zulu Cycad Encephalartos transvenosus Modjadji Giant-cycad Encephalartos venetus Blue Cycad Encephalartos woodii Wood's Giant-cycad PODOCARPACEAE Yellowwood Podocarpus Yellowwood Podocarpus elongatus Breede River Yellowwood