“Digital Game II”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867

Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867 12-28-1867 Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867 Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/banner1867 Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation "Mount Vernon Democratic Banner December 28, 1867" (1867). Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867. 34. https://digital.kenyon.edu/banner1867/34 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mount Vernon Banner Historic Newspaper 1867 by an authorized administrator of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. /4ii- '\. /!L-__,_-fk.._ ~-'r,.J-~. -- J Kfi ·)./47 II.VA! Ii' ' ,<?'-'· h Ir. ~ J L ~ /4l.~~, --~:<"'7~ :- --- _.:: =----- ' -----~-s.~--l!P VOLUl\iE XXXI. MOUNT VERNON. OHIO: S~\TURDAY, DECEI\IBER 28. 1867. NUMBER 36. lrritten for tlte ..Jlt. Jre1 non Bam1er. In addition fo the aLove, tlie following re How the Heathen Rage. 'J.'ct·l'iMc Railro:ul Cal:uuit!' ! 'l'IIE 'l'A 'l''l'LERS. WI Sol't~ of f.l:~rngrQpn;;. Qtge ~cmocrntic ~mrner ceiverl slight injur,es: H. M. Ruesell, Frank· The disrnppointment ofeomc 01 the ltadicale --------~--~,--,_, ______ _ iS PtrBLtSllf,:D P.V..ERlr SA.TURDA.Y UORNlNO BY OCye ~rm.ocratic ~nnnc.r Jin, 'renn.j J. Brown, Buffalo; J. Owy~t', New Brown nn,! Trumbull, contestnots in th6 at the action of Congress on impeachment is RY T'iPPA. Sll!'\DON?-,"ET, FH'TY-FIVE PERSOXS KILLED! York; J. -

PDF Van Tekst

Onze Taal. Jaargang 73 bron Onze Taal. Jaargang 73. Genootschap Onze Taal, Den Haag 2004 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_taa014200401_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. 1 [Nummer 1] Onze Taal. Jaargang 73 4 Vervlakt de intonatie? Ouderen en jongeren met elkaar vergeleken Vincent J. van Heuven - Fonetisch Laboratorium, Universiteit Leiden Ouderen kunnen jongeren vaak maar moeilijk verstaan. Ze praten te snel, te slordig en vooral te monotoon, zo luidt de klacht. Zou dat wijzen op een verandering? Wordt de Nederlandse zinsmelodie inderdaad steeds vlakker? Twee onderzoeken bieden meer duidelijkheid. Ik heb twee zoons in de adolescente leeftijdsgroep, zo tussen de 16 en de 20. Toen ik ze nog dagelijks om me heen had (ze zijn inmiddels technisch gesproken volwassen en het huis uit), mocht ik graag luistervinken als ze in gesprek waren met hun vrienden. Dan viel op dat alle jongens, niet alleen de mijne, snel spraken, met weinig stemverheffing, en vooral met weinig melodie. Het leek wel of ze het erom deden. Een Amerikaanse collega, die elk jaar een paar weken bij mij logeert om zijn Nederlands bij te houden, gaf ongevraagd toe dat hij in het algemeen weinig moeite heeft om Nederlanders te verstaan, behalve dan mijn zoons en hun vrienden. Een paar jaar eerder was ik in een onderzoek beoordelaar van de uitspraak van 120 Nederlanders, in leeftijd variërend van puber tot bejaarde. Mij viel op dat de bejaarden zo veel prettiger waren om naar te luisteren. Niet alleen spraken ze langzamer dan de jongeren, maar vooral maakten ze veel beter gebruik van de mogelijkheden die onze taal biedt om de boodschap met behulp van het stemgebruik te structureren. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

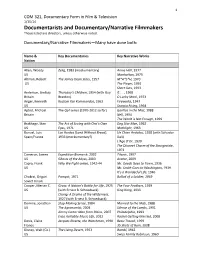

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

Michael Moore: a Man on a Mission Or How Far A

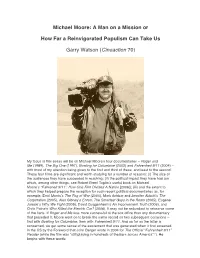

Michael Moore: A Man on a Mission or How Far a Reinvigorated Populism Can Take Us Garry Watson (Cineaction 70) My focus in this essay will be on Michael Mooreʼs four documentaries – Roger and Me (1989), The Big One (1997), Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) – with most of my attention being given to the first and third of these, and least to the second. These four films are significant and worth studying for a number of reasons: (i) The size of the audiences they have succeeded in reaching; (ii) the political impact they have had (on which, among other things, see Robert Brent Toplinʼs useful book on Michael Mooreʼs “Fahreneit 9/11”: How One Film Divided A Nation [2006]); (iii) and the extent to which they helped prepare the reception for such recent political documentaries as, for example, Errol Morrisʼs The Fog of War (2004), Mark Achbar and Jennifer Abbottʼs The Corporation (2005), Alex Gibneyʼs Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005), Eugene Jareckiʼs Why We Fight (2005), David Guggenheimʼs An Inconvenient Truth (2006), and Chris Paineʼs Who Killed the Electric Car? (2006). It may not be redundant to rehearse some of the facts. If Roger and Me was more successful at the box office than any documentary that preceded it, Moore went on to break the same record on two subsequent occasions – first with Bowling for Columbine, then with Fahrenheit 9/11. And as far as the latter is concerned, we get some sense of the excitement that was generated when it first screened in the US by the Foreword that John Berger wrote in 2004 for The Official “Fahrenheit 9/11” Reader (while the film was “still playing in hundreds of theaters across America”1). -

TYLER WILSON Lead Artist Tylerwilson.Art Vancouver, BC [email protected] +1-604-771-4577

TYLER WILSON Lead Artist tylerwilson.art Vancouver, BC [email protected] +1-604-771-4577 Summary ● 10 years of Leadership experience and 20 years in the game industry. ● Detail oriented, organized, and technical (rigs, problem solving, pipelines, best practices) ● Excellent written communication as well as documentation and tutorial experience. ● Always working towards the big picture studio goals. ● Loves: Games, Film, Anatomy Sculpts, Cloth Sims, Mentoring, Hockey. Skills Tools ● Character Creation ● Maya, XGen ● Digital Tailoring ● 3ds Max ● Technical Art ● ZBrush ● Scheduling & Organization ● Marvelous Designer ● Outsourcing ● Substance Painter, Mari ● Leadership ● Marmoset Toolbag, Keyshot, Arnold Experience Lead Artist Oct 2019 – Present Brass Token Games ● Provide overall artistic leadership and review all art assets for quality and continuity with the Creative Director’s vision. ● Light key assets through static and dynamic lighting. ● Help and manage art outsourcers to provide feedback, determine opportunities for efficiencies and cost savings, and help integrate art assets into the engine. ● Support the creation of marketing and pitch materials. Digital Tailor Mar 2019 – Present Freelance ● Continued creation of many items of clothing and complete outfits including accessories for Brud. Brud is a transmedia studio that creates digital character driven story worlds (Virtual Digital Influencers). ● Created two versions of a clean room tyvek Scientist outfit for System Shock 3, before and after Mutant infection. Lead Artist Mar 2016 – Mar 2019 Hothead Games ● Manage a team of twelve internal artists including 1on1's and mentoring. ● Set the art direction and worked closely with the team to reach our goals. ● Featured by Apple in "Gloriously Gorgeous Games" category. ● Brought high fidelity art to the mobile market. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

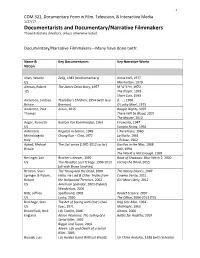

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film, Television, & Interactive Media 1/27/17 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anderson, Paul Junun, 2015 Boogie Nights, 1997 Thomas There Will be Blood, 2007 The Master, 2012 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Antonioni, Ragazze in bianco, 1949 L’Avventura, 1960 Michelangelo Chung Kuo – Cina, 1972 La Notte, 1961 Italy L'Eclisse, 1962 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Berlinger, Joe Brother’s Keeper, 1992 Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, 2000 US The Paradise Lost Trilogy, 1996-2011 Facing the Wind, 2015 (all with Bruce Sinofsky) Berman, Shari The Young and the Dead, 2000 The Nanny Diaries, 2007 Springer & Pulcini, Hello, He Lied & Other Truths from Cinema Verite, 2011 Robert the Hollywood Trenches, 2002 Girl Most Likely, 2012 US American Splendor, 2003 (hybrid) Wanderlust, 2006 Blitz, Jeffrey Spellbound, 2002 Rocket Science, 2007 US Lucky, 2010 The Office, 2006-2013 (TV) Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, -

Descargar Bomberman Blast Wii Iso

Descargar bomberman blast wii iso Continue Progress continues We have already had 10,965 updates with Dolphin 5.0. Follow Dolphin's ongoing progress through the Dolphin blog: August/September 2019 Progress Report. The Bomberman Blast Wii IsoBomberman Blast Wii ControlsBomberman Blast is an action game developed and published by Hudson Soft for the Wii and WiiWare. It is part of the Bomberman series. This is the second in the bomberman downloadable games trilogy, after Bomberman Live for Xbox Live Arcade, followed by Bomberman Ultra for PlayStation Network. The game was released in two versions: full featured retail release and downloadable, lower-priced WiiWare. Bomberman Blast is originally a retail game. Featuring a whole new story mode, just like the old games as well as the 8-player online combat mode, it seemed like Hudson was trying. Vicky's dolphin emulator needs your help! Dolphin can play thousands of games and changes happen all the time. Help us keep up! Join us and help us make this the best resource for the dolphin. Bomberman BlastDeveloper (s)Hudson SoftPublisher (s)Hudson EntertainmentSeriesBombermanPlatform (s)WiiRelease Date (s) JP September 25, 2008Genre (s)ActionMode (s)Single game, Multiplayer (8)Entry TechniquesWi Remote, GameCube ControllerCompatibility5PerfectIGameSRB668 The WiiWare VersionDolphin Forum threadOpen IssuesSearch GoogleSearch WikipediaBomberman Blast (Bomberman in Japan) is a brand new addition to the Bomberman series available on WiiWare. Up to eight players can fight online at the same time via Nintendo Wi-Fi Connection. Simple controls make this a great game for family and friends to enjoy at any time. You can summon new items by shaking the Wii Remote Controller, creating new levels of Bomberman excitement. -

Data Analysis for Sector Recommendations

DISTRICT OF SQUAMISH DATA ANALYSIS FOR SECTOR RECOMMENDATIONS PREPARED FOR: FOREWORD The modern-day economy of Squamish has significantly evolved from a century ago when it was a southern railway terminus. Squamish was built on its foundation of logging and tourism stimulated by transportation and railway improvements, proximity to natural resources and regional markets, and the establishment of largescale, industrial manufacturing as well as deep-water break-bulk facilities. Squamish is on the cusp of monumental change and is well positioned to share in British Columbia’s (BC’s) leading economic and job growth for Canada. Squamish is leveraging its favorable geography, multitude of recreational assets and its quality of life amenities as part of its economic diversification strategy. Several emerging sectors have experienced firm and employment growth, including hospitality and tourism; knowledge-based industries and education; clean energy; high tech; media production; and light manufacturing. To build upon its current momentum, it is paramount that Squamish prioritize areas for economic growth with a strategic approach and efficient planning. This report focuses on target industries suited for driving community wealth and is the precursor to a more comprehensive action plan. This in turn, will provide insight to maximize the positive impact derived from these targeted industries. Economic Development Office, District of Squamish EXECUTIVE SUMMARY From 2017 to present, British Columbia has experienced Canada's highest economic and employment growth and lowest inflation. Gross Domestic Product in the province rose by 3.9% in 2017, up from 3.6% in 2016. Though natural resources, transportation/warehousing, construction, professional services, education and manufacturing are some of the largest job providers in B.C., the province has emerged as a leader in subsectors, at the intersection of traditional sectors and new technologies. -

Abstract the Goal of This Project Is Primarily to Establish a Collection of Video Games Developed by Companies Based Here In

Abstract The goal of this project is primarily to establish a collection of video games developed by companies based here in Massachusetts. In preparation for a proposal to the companies, information was collected from each company concerning how, when, where, and why they were founded. A proposal was then written and submitted to each company requesting copies of their games. With this special collection, both students and staff will be able to use them as tools for the IMGD program. 1 Introduction WPI has established relationships with Massachusetts game companies since the Interactive Media and Game Development (IMGD) program’s beginning in 2005. With the growing popularity of game development, and the ever increasing numbers of companies, it is difficult to establish and maintain solid relationships for each and every company. As part of this project, new relationships will be founded with a number of greater-Boston area companies in order to establish a repository of local video games. This project will not only bolster any previous relationships with companies, but establish new ones as well. With these donated materials, a special collection will be established at the WPI Library, and will include a number of retail video games. This collection should inspire more people to be interested in the IMGD program here at WPI. Knowing that there are many opportunities locally for graduates is an important part of deciding one’s major. I knew I wanted to do something with the library for this IQP, but I was not sure exactly what I wanted when I first went to establish a project. -

Sega Mega Drive™ Ultimate Collection Announced for the Xbox 360 and Playstation 3

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE SEGA MEGA DRIVE™ ULTIMATE COLLECTION ANNOUNCED FOR THE XBOX 360 AND PLAYSTATION 3 SEGA’s glorious past is gathered in one colossal collection LONDON & SAN FRANCISCO (November 3, 2008) – SEGA® of Europe Ltd. and SEGA® of America, Inc today announced the development of SEGA Mega Drive Ultimate Collection for the Xbox 360® video game and entertainment system from Microsoft, and the PLAYSTATION®3 computer entertainment system. This compilation will feature the best first-party games from SEGA’s respected 16-bit Mega Drive years, as well as bonus content from its 8-bit Master System and 1980’s arcade era games library. “SEGA Mega Drive Ultimate Collection is a must-have for any SEGA enthusiast,” commented Gary Knight, European Marketing Director for SEGA Europe. “Fans will get a chance to relive fond memories from these classic games in HD format.” Developed by Backbone Entertainment, SEGA Mega Drive Ultimate Collection contains over 40 celebrated SEGA classics in one package; making it the largest collection of SEGA first party games ever offered. Featured games include; Sonic the Hedgehog 1, 2 and 3, Columns, Alien Storm, Ecco the Dolphin, Space Harrier, and cult classic, Streets of Rage 1, 2 and 3. The games in the collection have been reproduced with the utmost detail and accuracy to commend their originals. In addition, SEGA Mega Drive Ultimate Collection can output the games in 720p with higher resolution graphics for HD televisions, bringing a new visual richness to these classic titles. SEGA Mega Drive Ultimate Collection for Xbox 360 and PLAYSTATION 3 is scheduled for worldwide release in early 2009. -

Hansoft Production Management and QA Tool Successfully Implemented by Radical Entertainment

2012-06-27 08:27 CEST Hansoft Production Management and QA Tool successfully implemented by Radical Entertainment Uppsala, Sweden – June 27, 2012 – Hansoft, the leading vendor of tools for project management and defect tracking for Agile and Lean game and software development, today announced that Radical Entertainment has successfully implemented Hansoft. “Radical Entertainment has been making video games since 1991, and during that time, we have developed our own cutting-edge proprietary technology, pipelines and processes. Our tools have served us incredibly well for over 20 years, so the adoption of Hansoft for production management is a massive statement of support. Hansoft's advanced tools, workflows, flexibility, and strong support will significantly increase the efficiency and effectiveness of our production flow. This will allow us to focus even more on what we do best - making great games!,” said David Fracchia, Vice President Technology at Radical. Hansoft project management and QA tool has helped the world’s most demanding developers increase productivity and ship better software faster for nearly a decade. Agile and lean development, collaborative scheduling, real-time reporting, bug tracking / QA, workload coordination, portfolio and document management are tightly integrated in one real-time updated solution, flexible to bend to the needs of a specific organization. “Leading studios around the world like Radical Entertainment are our customers, and since they are already themselves developing cutting edge tools and technology, they are a very demanding community to serve. But this is what we thrive on, continuously pushing forward with new releases making development simpler for the teams and enabling new more productive ways of working.