The Histories Hidden in the Periodic Table

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHEMISTRY for the Bottom of the Periodic Table

http://cyclotron.tamu.edu CHEMISTRY for the Bottom of the Periodic Table Techniques to investigate chemical properties of superheavy elements lead to improved methods for separating heavy metals THE SCIENCE The chemical properties of superheavy element 113, nihonium, are almost completely unknown, so a team of researchers from the Cyclotron Institute at Texas A&M University and the Institut Pluridisciplinaire Hubert Curien in France are developing techniques that could be used to study this fleeting element. As part of that effort, they are comparing the properties of nihonium to the chemically similar elements indium and thallium; to do so, the team studied the separation of these two elements using a new class of designer molecules called ionic liquids. THE IMPACT Measuring the chemical properties of nihonium and other superheavy elements will increase our understanding of the principles that control the Periodic Table. Comparing the data from nihonium to results for similar elements, obtained using the team’s fast, efficient, single-step process, reveals trends that arise from the structure of the Periodic Table. This research could also lead to better methods of re- using indium, a metal that is part of flat-panel displays but not currently mined in the United States. The proposed mechanism of transfer. Thallium (Tl) bonds with chlorine (Cl) and moves into the ionic liquid (in blue). SUMMARY The distribution of indium and thallium between the aque- ous and organic phases is the key to understanding the PUBLICATIONS separation of these elements. An aqueous solution, con- E.E. Tereshatov, M. Yu. Boltoeva, V. Mazan, M.F. -

IUPAC Wire See Also

News and information on IUPAC, its fellows, and member organizations. IUPAC Wire See also www.iupac.org Flerovium and Livermorium Join the Future Earth: Research for Global Periodic Table Sustainability n 30 May 2012, IUPAC officially approved he International Council for Science (ICSU), of the name flerovium, with symbol Fl, for the which IUPAC is a member, announced a new Oelement of atomic number 114 and the name T10-year initiative named Future Earth to unify livermorium, with symbol Lv, for the element of atomic and scale up ICSU-sponsored global environmental- number 116. The names and symbols were proposed change research. by the collaborating team of the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (Dubna, Russia) and the Lawrence Operational in 2013, this new ICSU initiative will Livermore National Laboratory (Livermore, California, provide a cutting-edge platform to coordinate scien- USA) to whom the priority for the discovery of these tific research to respond to the most critical social and elements was assigned last year. The IUPAC recom- environmental challenges of the 21st century at global mendations presenting these names is to appear in and regional levels. “This initiative will link global envi- the July 2012 issue of Pure and Applied Chemistry. ronmental change and fundamental human develop- ment questions,” said Diana Liverman, co-director of The name flerovium, with symbol Fl, lies within the Institute of the Environment at the University of tradition and honors the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Arizona and co-chair of the team Reactions in Dubna, Russia, where the element of that is designing Future Earth. -

Quest for Superheavy Nuclei Began in the 1940S with the Syn Time It Takes for Half of the Sample to Decay

FEATURES Quest for superheavy nuclei 2 P.H. Heenen l and W Nazarewicz -4 IService de Physique Nucleaire Theorique, U.L.B.-C.P.229, B-1050 Brussels, Belgium 2Department ofPhysics, University ofTennessee, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996 3Physics Division, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, Tennessee 37831 4Institute ofTheoretical Physics, University ofWarsaw, ul. Ho\.za 69, PL-OO-681 Warsaw, Poland he discovery of new superheavy nuclei has brought much The superheavy elements mark the limit of nuclear mass and T excitement to the atomic and nuclear physics communities. charge; they inhabit the upper right corner of the nuclear land Hopes of finding regions of long-lived superheavy nuclei, pre scape, but the borderlines of their territory are unknown. The dicted in the early 1960s, have reemerged. Why is this search so stability ofthe superheavy elements has been a longstanding fun important and what newknowledge can it bring? damental question in nuclear science. How can they survive the Not every combination ofneutrons and protons makes a sta huge electrostatic repulsion? What are their properties? How ble nucleus. Our Earth is home to 81 stable elements, including large is the region of superheavy elements? We do not know yet slightly fewer than 300 stable nuclei. Other nuclei found in all the answers to these questions. This short article presents the nature, although bound to the emission ofprotons and neutrons, current status ofresearch in this field. are radioactive. That is, they eventually capture or emit electrons and positrons, alpha particles, or undergo spontaneous fission. Historical Background Each unstable isotope is characterized by its half-life (T1/2) - the The quest for superheavy nuclei began in the 1940s with the syn time it takes for half of the sample to decay. -

No. It's Livermorium!

in your element Uuh? No. It’s livermorium! Alpha decay into flerovium? It must be Lv, saysKat Day, as she tells us how little we know about element 116. t the end of last year, the International behaviour in polonium, which we’d expect to Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry have very similar chemistry. The most stable A(IUPAC) announced the verification class of polonium compounds are polonides, of the discoveries of four new chemical for example Na2Po (ref. 8), so in theory elements, 113, 115, 117 and 118, thus Na2Lv and its analogues should be attainable, completing period 7 of the periodic table1. though they are yet to be synthesized. Though now named2 (no doubt after having Experiments carried out in 2011 showed 3 213 212m read the Sceptical Chymist blog post ), that the hydrides BiH3 and PoH2 were 9 we shall wait until the public consultation surprisingly thermally stable . LvH2 would period is over before In Your Element visits be expected to be less stable than the much these ephemeral entities. lighter polonium hydride, but its chemical In the meantime, what do we know of investigation might be possible in the gas their close neighbour, element 116? Well, after phase, if a sufficiently stable isotope can a false start4, the element was first legitimately be found. reported in 2000 by a collaborative team Despite the considerable challenges posed following experiments at the Joint Institute for by the short-lived nature of livermorium, EMMA SOFIA KARLSSON, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN STOCKHOLM, KARLSSON, EMMA SOFIA Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Russia. -

The Quest to Explore the Heaviest Elements Raises Questions About How Far Researchers Can Extend Mendeleev’S Creation

ON THE EDGE OF THE PERIODIC TABLE The quest to explore the heaviest elements raises questions about how far researchers can extend Mendeleev’s creation. BY PHILIP BALL 552 | NATURE | VOL 565 | 31 JANUARY 2019 ©2019 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All ri ghts reserved. ©2019 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All ri ghts reserved. FEATURE NEWS f you wanted to create the world’s next undiscovered element, num- Berkeley or at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, ber 119 in the periodic table, here’s a possible recipe. Take a few Russia — the group that Oganessian leads — it took place in an atmos- milligrams of berkelium, a rare radioactive metal that can be made phere of cold-war competition. In the 1980s, Germany joined the race; I only in specialized nuclear reactors. Bombard the sample with a beam an institute in Darmstadt now named the Helmholtz Center for Heavy of titanium ions, accelerated to around one-tenth the speed of light. Ion Research (GSI) made all the elements between 107 and 112. Keep this up for about a year, and be patient. Very patient. For every The competitive edge of earlier years has waned, says Christoph 10 quintillion (1018) titanium ions that slam into the berkelium target Düllmann, who heads the GSI’s superheavy-elements department: — roughly a year’s worth of beam time — the experiment will probably now, researchers frequently talk to each other and carry out some produce only one atom of element 119. experiments collaboratively. The credit for creating later elements On that rare occasion, a titanium and a berkelium nucleus will collide up to 118 has gone variously, and sometimes jointly, to teams from and merge, the speed of their impact overcoming their electrical repul- sion to create something never before seen on Earth, maybe even in the Universe. -

Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants John Dustin Despotopulos University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Chemistry Commons Repository Citation Despotopulos, John Dustin, "Studies of Flerovium and Element 115 Homologs with Macrocyclic Extractants" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2345. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645877 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INVESTIGATION OF FLEROVIUM AND ELEMENT 115 HOMOLOGS WITH MACROCYCLIC EXTRACTANTS By John Dustin Despotopulos Bachelor of Science in Chemistry University of Oregon 2010 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy -

Superheavy Elements: Existence, Classification and Experiment

UDC 541.2 Superheavy elements: existence, classification and experiment V.A.Kostyghin1, V.M.Vaschenko2, Ye.A.Loza2 1 "Akvatekhinzhiniring", Cherkassy, Ukraine, e-mail:[email protected] 2 State Ecological academy for post-graduate education and management, Kyiv, Ukraine, e-mail:[email protected] This paper proposes spatial periodic table developed based on classic electron shell structure model. The periodic table determines location and chemical properties of superheavy elements. 14 new long-living superheavy elements found by Proton-21 laboratory and one long-living superheavy element found by A.Marinov were identified. Introduction At present there are 118 elements known [1]. However, there are only 104 of them well-studied. The superheavy nuclei existence problem and also nuclones collective states problems (super-nuclei, nuclear associations, multi-nuclei clusters, nuclear condensate etc.) long ago have become subject of experimental and theoretical research [2-7]. This problem is specially important for modern astrophysical concepts [8-10]. The main branch of experimental research of superheavy nuclei isotopes and exotic isotopes of light nuclei is a new elements synthesis by different accelerator with latter investigation of nuclei collision results. However this method has two important and unsolved problems [11, 12]. The first one is the excess energy of the synthesized nucleus. The energy required to overcome the Coulomb barrier during the nuclei collision transforms 1 into internal energy of the newly formed nucleus and it is usually enough for instant nuclei fission, because the internal clusters of the nuclei have energy over Coulomb barrier. This leads to a very complex experimental task of "discharge" of excess energy by high-energy particle radiation - gamma-quantum, neutron, positron, proton, alpha-particle [13] etc. -

Quasifission in Heavy and Superheavy Element Formation Reactions

EPJ Web of Conferences 131, 04004 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201613104004 Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements Quasifission in heavy and superheavy element formation reactions D.J. Hinde1, a , M. Dasgupta1, D.Y. Jeung1, G. Mohanto1, b , E. Prasad1, c , C. Simenel1, J. Walshe 1, A. Wahkle1, d , E. Williams1, I.P. Carter1, K.J. Cook1, Sunil Kalkal1, D.C. Rafferty1, R. du Rietz1, e , E.C. Simpson1, H.M. David2, Ch.E. Düllmann2,3,4, and J. Khuyagbaatar2,3 1 Department of Nuclear Physics, Research School of Physics and Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia 2 GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung, 64291 Darmstadt, Germany 3 Helmholtz Institute Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany 4 Johannes Gutenberg Universität Mainz, 55099 Mainz, Germany Abstract. Superheavy elements are created in the laboratory by the fusion of two heavy nuclei. The large Coulomb repulsion that makes superheavy elements decay also makes the fusion process that forms them very unlikely. Instead, after sticking together for a short time, the two nuclei usually come apart, in a process called quasifission. Mass-angle distributions give the most direct information on the characteristics and time scales of quasifission. A systematic study of carefully chosen mass-angle distributions has provided information on the global trends of quasifission. Large deviations from these systematics reveal the major role played by the nuclear structure of the two colliding nuclei in determining the reaction outcome, and thus implicitly in hindering or favouring superheavy element production. Superheavy elements (SHE) are formed by heavy-ion fusion reactions. Their cross sections are significantly suppressed [1] by the quasifission process [2]. -

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title SUPERHEAVY ELEMENTS Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4qh151mc Author Thompson, S.G. Publication Date 1972-05-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Submitted to Science LBL-665 .. r" Preprint ~. SUP ERHEA VY ELEMENTS S. G. Thompson and C. F. Tsang May 1972 AEC Contract No. W -7405 -eng-48 TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY This is a library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Diu is ion, Ext. 5545 ..,Ul. DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain coiTect information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any waiTanty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. LBL-665 Thompson 1 SUPERHEAVY ELEMENTS s. -

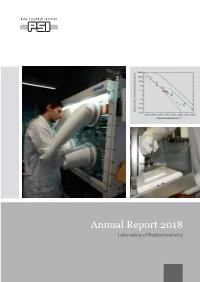

Annual Report 2018 Laboratory of Radiochemistry Cover Transmutation Can Potentially Mitigate Problems Related to the Disposal of Spent Nuclear Fuel

Annual Report 2018 Laboratory of Radiochemistry Cover Transmutation can potentially mitigate problems related to the disposal of spent nuclear fuel. In a prominent class of advanced fast nuclear reactors designed for this purpose, liquid metals are planned to be used as coolants. In the Isotope and Target Chemistry group of LRC, we study the release of radionuclides from liquid metals to support safety assessments for these liquid metal cooled reactors. Photographs: Members of the Target and Isotope Chemistry group performing experiments with liquid metal samples Graph: Results of experiments studying the evaporation iodine from liquid lead- bismuth eutectic. Annual Report 2018 Laboratory of Radiochemistry Editors R. Eichler, A. Blattmann Paul Scherrer Institut Reports are available from Labor für Radiochemie Angela Blattmann 5232 Villigen PSI [email protected] Switzerland Paul Scherrer Institut Durchwahl +41 56 310 24 04 5232 Villigen PSI Sekretariat +41 56 310 24 01 Switzerland Fax +41 56 310 44 35 See also our web-page https://www.psi.ch/lrc/ I TABLE OF CONTENTS Editorial................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 SUPERHEAVY ELEMENT 112Cn & 114Fl - CHALCOGEN INTERACTIONS USING GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY . 3 P. Ionescu, R. Eichler, B. Kraus, Y. Wittwer, R. Dressler, H. Gäggeler, D. Herrmann, A. Vögele, A. Türler, N.V. Aksenov, Y.V. Albin, G.A. Bozhikov, V.I. Chepigin, I. Chupranov, S.N. Dmitriev, A.S. Madumarov, O.N. Malyshev, Y.A. Popov, A.V. Sabelnikov, P. Steinegger, A.I. Svirikhin, G.K. Vostokin, A.V. Yeremin, T.S. Sato, N.M. Chiera 211 INSIGHTS INTO SURFACE REACTIONS OF Pb WITH SiO2 AND Al2O3 ON THE SINGLE-ATOM SCALE .............................................................................................................................................................................. -

Experimental Search for Superheavy Elements

THE HENRYK NIEWODNICZAŃSKI INSTITUTE OF NUCLEAR PHYSICS POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES UL. RADZIKOWSKIEGO, 31-342 KRAKÓW, POLAND WWW.IFJ.EDU.PL/PUBL/REPORTS/2008/ KRAKÓW, DECEMBER 2008 REPORT No. 2019/PL Experimental search for superheavy elements Andrzej Wieloch* Habilitation thesis (prepared in March 2008) *M. Smoluchowski Institute of Physics, Jagiellonian University. Reymonta 4. 30-059 Kraków, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This work reports on the experimental search for superheavy elements (SHE). Two types of approaches for SHE production are studied i.e.: "cold" fusion mech anism and massive transfer mechanism. First mechanism was studied, in normal and inverse kinematics, by using Wien filter at the GANIL facility. The production of elements with Z=106 and 108 is reported while negative result on the synthesis of SHE elements with Z=114 and 118 was received. The other approach i.e. re actions induced by heavy ion projectiles (e.g.:172Yb. 197Au) on fissile target nuclei (e.g.: 2S8U., 2S2Th) at near Coulomb barrier incident energies was studied by using superconducting solenoid installed in Texas A&M University. Preliminary results for the reaction 197 Au(7.5MeV/u) -f 232Th are presented where three cases of the possible candidates for SHE elements were found. A dedicated detection setup for such studies is discussed and the detailed data analysis is presented. Detection of al pha and spontaneous fission radioactive decays is used to unambiguously identify the atomic number of SHE. Special statistical analysis for a very low detected number of a decays is applied to check consistency of the a radioactive chains. -

Status and Perspectives of the Dubna Superheavy Element Factory

EPJ Web of Conferences 131, 08001 (2016) DOI: 10.1051/epjconf/201613108001 Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements Status and perspectives of the Dubna superheavy element factory Sergey Dmitrieva , Mikhail Itkis, and Yuri Oganessian Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions, Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, 141980 Dubna, Russian Federation Abstract. In the Flerov Laboratory of Nuclear Reactions, Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (FLNR JINR), construction of a new experimental complex is currently in progress (Superheavy Element Factory), aimed at the synthesis of new superheavy nuclides and the detailed study of those already synthesized. The project includes the construction of a new accelerator of stable and long-lived isotopes in the mass range A = 10–100 with an intensity of up to 10 pµA and energy up to 8 MeV/nucleon; con- struction of a new experimental building and infrastructure for housing the accelerator with five channels for the transportation of beams to a 1200-m2 experimental hall that is equipped with systems of shielding and control for operations with radioactive materials; development of new separators of reaction products; upgrade of the existing separators and development of the new detection modules for the study of nuclear, atomic, and chemical properties of new elements. The first experiments are planned for 2018. 1. Introduction The six heaviest chemical elements with atomic numbers 113 to 118 that fill the 7th row of Mendeleev’s Periodic Table were synthesized in reactions of 48Ca ions with actinide targets in the experimental studies carried out over the recent years. Over 50 new isotopes of elements 104 to 118 with maximum neutron excess were for the first time produced and their decay properties were determined in these investigations [1, 2].